Takahiro Ueyama

Japan’s government hopes that a ¥10-trillion (US$75-billion) fund will kickstart a new era of discovery and innovation for some of the country’s most prestigious universities. The plan seeks to emulate the model underpinning many of the leading private research institutions in the United States, where endowments worth billions of dollars produce regular financial returns to sustain running costs.

Takahiro Ueyama, of the Japanese government’s Council for Science, Technology and Innovation, is the plan’s key architect.

What problems are you trying to fix with this fund?

After 2004, national universities were incorporated as quasi-private universities. But the new system has hindered researchers’ and professors’ efficiency because it created a lot of paperwork. How are we to create independent, autonomous research universities? To be independent, you have your own robust, financial base. The Harvard University endowment is worth about $50 billion. UK universities such as Cambridge and Oxford have also been growing their endowments. Our universities cannot compete with this and nobody would accept it if we gave a huge amount of taxpayers’ money directly to, say, the University of Tokyo. The only method we hit upon is the endowment fund. This is unprecedented in higher-education administration in our country. It’s the big moment to change how things are done.

At some point, do you want universities to take over the endowment?

Universities here have no experience in endowments. To run an endowment, universities will need to employ investment professionals and acquire money from wealthy people in the form of donations. They don’t know how to do this, so we will transfer the know-how we have acquired in the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) to probably four to six selected universities. The bottom line is that we want each university to be independent, not controlled by the government, and we need a kind of preparation period for them to become autonomous and independent.

What should Japanese universities and other research institutes do to encourage more younger scientists, especially women, into research?

Our focus should be on young researchers. The reduction of block funding [government payments given periodically to universities] has particularly affected younger researchers in recent years. The new money should create different kinds of opportunities for the younger generation. Harvard University has almost the same number of faculty members as the University of Tokyo, but it has a much larger number of technicians and administrators who support them. Because of the reduction in block funding in this country, scientists and engineers have to do too much administrative work. We need to expand the research time for younger researchers by employing assistants and administrators.

Has the ability for Japanese scientists to work internationally improved? What more could academic institutions do to foster this cross-border collaboration?

In the 1980s, when I was at Stanford University in California, many young Japanese people went abroad to do PhDs and engage in collaborative research, but the number has decreased rapidly. We need to encourage young people to go abroad and into the inner circle of scientists. That is the only way we can recover the productivity of research in our country. The money the fund provides should be used to encourage younger scientists to do international collaborative work.

What role should the government play in setting the research agenda for institutions and scientists in Japan?

We will give some advice, but not government advice. It will come from an outside board, consisting of former presidents or foreign experts or business people. Universities have to think for themselves.

There has been criticism that this fund will allow the government to meddle in academia.

That’s completely wrong. We want each university to be independent, because autonomy is the essence of any research university. As long as any university is under the umbrella of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, there are a lot of regulations. Such regulations hinder research universities from being independent.

There has also been concern that the fund could be used to nudge research towards the natural sciences, and away from the social sciences and humanities, is that fair?

No, we amended the basic role of science and technology law to include humanities and social science in government policy. From now on, JST funding will be used for the humanities and social sciences. It is ridiculous to separate these disciplines from all science because they are part of academia. The humanities and social sciences are going to be very important to give a strategic framework for science, such as with artificial intelligence.

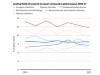

Is Japan’s research decline turning a corner?

Is Japan’s research decline turning a corner?

How Japanese science is trying to reassert its research strength

How Japanese science is trying to reassert its research strength

Japan’s leading international partnerships

Japan’s leading international partnerships

Freeing up Japan’s PhD potential

Freeing up Japan’s PhD potential

Japan’s rising research stars: Mariko Kimura

Japan’s rising research stars: Mariko Kimura

Japan’s rising research stars: Yuuki Wada

Japan’s rising research stars: Yuuki Wada

Japan’s rising research stars: Tatsuya Kubota

Japan’s rising research stars: Tatsuya Kubota

Japan’s rising research stars: Yasuka Toda

Japan’s rising research stars: Yasuka Toda

Japan’s rising research stars: Ken-ichi Otake

Japan’s rising research stars: Ken-ichi Otake

Will Japan’s new ¥10-trillion university fund lift research performance?

Will Japan’s new ¥10-trillion university fund lift research performance?

How Japan’s disciplinary strengths are shifting focus

How Japan’s disciplinary strengths are shifting focus

Japanese robotics lags as AI captures global attention

Japanese robotics lags as AI captures global attention