In 1972, three years after humans first reached the Moon, Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan was the last to leave it.Credit: NASA

As I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come — but we believe not too long into the future — I’d like to just say what I believe history will record: that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.

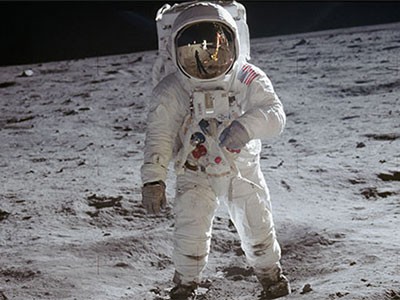

These words were spoken by Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan on 14 December 1972, as he prepared to return home from the Moon. With Neil Armstrong’s “one giant leap for mankind”, little more than three years earlier, they bookended a grand human endeavour. After 50 years, they remain the last (officially prepared) words spoken on the Moon.

When Cernan, fellow Moon-walker Harrison Schmitt and command-module pilot Ronald Evans had blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida seven days earlier, it was already clear that this would be the last Apollo mission. But few anticipated that, 50 years on, human exploration of space would be confined to low Earth orbit. Apollo 17 still marks the last time boots crunched into the soil of an alien world; the last time astronauts skipped joyously in the Moon’s low gravity; the last time anyone directly witnessed Earth’s blue globe rising above the grey lunar horizon.

The $93-billion plan to put astronauts back on the Moon

For most of the eight billion people now on Earth, the Apollo era is legend; the main significance of the photograph of a ‘blue marble’ Earth taken from Apollo 17 is as one of the default iPhone wallpapers. But with the launch last month of the Artemis I mission, NASA finally seems to be intent on rekindling the glory days of Apollo. Humanity is about to make a giant leap again. But to what end?

As Cernan and Schmitt guided their lunar module into the narrow Taurus–Littrow valley, each had a personal mission. Cernan was looking to gain the status of Moon-walker, which he had just missed in 1969 as lunar-module pilot on Apollo 10, the practice run for Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s successful landing with Apollo 11 a couple of months later.

Schmitt, meanwhile, was a geologist — still the only professional scientist to walk on the Moon. He had pushed NASA to continue the Apollo programme, arguing that humans could do better science than robot landers. The Moon’s ancient rocks, much less erased by tectonics than those of Earth, could hold the key to a new understanding of the Solar System.

Cernan and Schmitt spent 3 days in Taurus–Littrow, and more than 22 hours walking and driving around the valley’s landslides and volcanic cinder cones. They put more than 35 kilometres on the odometer of their lunar rover and picked up 110 kilograms of rocks to bring home, the biggest haul of any Apollo mission.

Then, late on 14 December, they parked the rover with its television camera pointing at the lander, to broadcast their departure. They left a plaque that read, in part, “Here man completed his first explorations of the moon, December 1972, A.D.”. After the greatest human voyage ever, deep-space exploration just — stopped.

Political drivers

The reasons lay, above all, in the shifting sands of politics. The Apollo programme was brought rousingly to life by US president John F. Kennedy’s “We choose to go to the Moon” speech in September 1962, when he promised that there would be US boots on the lunar soil by the end of the decade. It was a geopolitical prestige project, a response to the country falling behind in the cold war space race. In 1957, the Soviet Union had launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1. It had also put the first man into orbit — Yuri Gagarin in 1961, just the previous year.

But less than a year after the United States achieved the first successful Moon landing, the axe fell on Apollo. The demise was triggered when, in April 1970, an oxygen tank exploded two days after the launch of the Apollo 13 mission, threatening the lives of the astronauts on board. Missions after Apollo 17 were cancelled. But this was something of a pretext. Apollo was ruinously expensive, and by the late 1960s it was clear that the United States was comfortably ahead in the race. US president Richard Nixon, who took office in 1969, needed to do something with NASA that Kennedy had not.

The crew of Apollo 17, the last mission to land on the Moon, took this iconic photograph of Earth in 1972.Credit: NASA

Money and attention began to shift to low Earth orbit. NASA launched the Skylab space station in 1973, and fired the boosters on its space-shuttle programme. It aimed to establish a permanent human presence in space — but a few hundred kilometres up, not roughly 400,000 kilometres away on the Moon. Space became a rare symbol of cold war cooperation. In 1975, the United States and Soviet Union orchestrated a real and symbolic in-orbit handshake when an Apollo module docked with a Soyuz one and astronauts met cosmonauts. By 1998, with the launch of the International Space Station, the two had entered permanent cohabitation in space.

Nature special: 50 years since the Apollo Moon landing

And there, in low Earth orbit, things have stayed. Members of Congress have kept alive dreams of a US return to deep space by funnelling funds to their districts for aerospace jobs. But the momentum has never been fully regained. In 1989, on the 20th anniversary of Apollo 11, president George H. W. Bush announced an expensive push to return to the Moon and travel on to Mars. This ended four years later, the absence of a space race depriving it of great political support. In 2004, president George W. Bush tried again, with a more modest proposal for renewed lunar exploration. That came a year after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated on re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, killing its crew of seven and signalling the beginning of the end for the shuttle programme. This Bush plan got enough traction for NASA to begin building a new generation of Moon rockets — before president Barack Obama cancelled the programme in 2010, citing cost.

Then, the cycle was broken. In 2017, during Donald Trump’s presidency, Republican space-policy advisers crafted a fresh plan to return astronauts to the Moon. Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator at the time, championed the programme and named it Artemis, after the ancient Greek goddess of the Moon, sister to the Sun god Apollo. For whatever reason, Joe Biden kept it on when he became president in 2021.

Science and strategy

To be sure, there are renewed scientific imperatives to return to the Moon. In the 1990s, researchers using orbiting spacecraft discovered frozen water on the lunar surface, showing that it was not bone-dry as once thought. That water could reveal secrets of the Solar System’s history – as well as being one thing we wouldn’t have to transport to a permanent lunar base.

But the sort of science that motivated Schmitt is the least of the reasons behind the renewed push. Technology and politics are again pertinent. Artemis is hugely expensive, projected to cost US$93 billion by 2025, but so far the costs are building slowly enough that members of Congress are allowing NASA small annual budget increases for it. The rise of powerful private companies such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, based in Hawthorne, California, has brought new public enthusiasm for space exploration, as well as new ways of delivering it. NASA has contracted SpaceX to deliver Artemis astronauts to the lunar surface using the enormous Starship, with which Musk dreams of colonizing Mars.

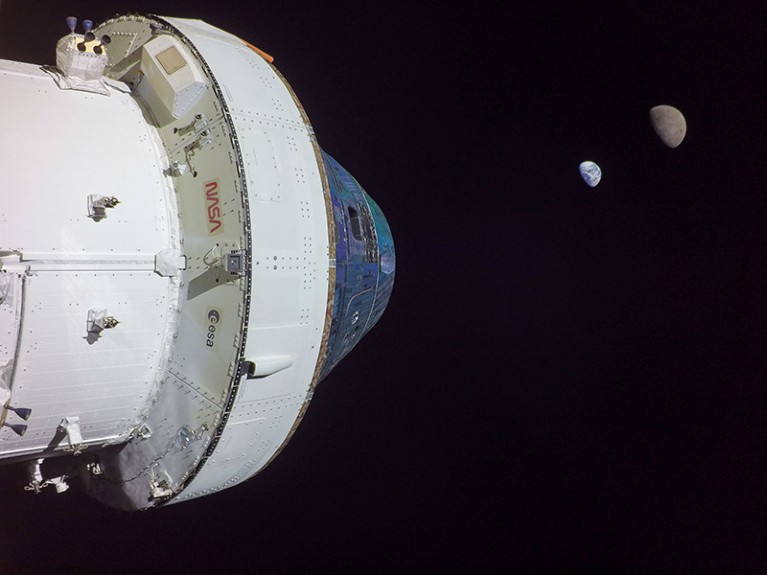

The Orion capsule, shown during the Artemis I mission, could soon return people to the Moon.Credit: ESA/NASA

And then there is the looming influence of China, which has just finished building the main phase of its first space station and might be planning to land astronauts on the Moon in the 2030s. To the more hawkish members of the US Congress, sending astronauts to other worlds is once again a geopolitical statement. A not-insignificant reason for the revival of human space exploration is that it is once more being seen as a space race.

Some remain unconvinced that Artemis is fit for purpose. Critics such as Lori Garver, a former NASA deputy administrator, says the agency could move faster and more nimbly in its partnerships with aerospace companies. Many would prefer NASA to forget deep space and spend more time and money on Earth, including space-based climate monitoring. Such comments echo criticisms from the 1960s, when much of the US public wanted the government to focus not on the space race, but on Earth-bound problems such as civil rights.

Lift off! Artemis Moon rocket launch kicks off new era of human exploration

Despite those criticisms, the launch of the Artemis I mission on 16 November has given the programme a huge boost. NASA’s new Moon rocket — a Frankenstein’s creature cobbled together from previous rocket programmes, including the one started by George W. Bush — sent the as-yet uncrewed Orion capsule to orbit the Moon, to see how it would hold up in the hostile environment of deep space. The second Artemis mission should fly around the Moon no earlier than 2024, this time with astronauts on board. The third mission will land people on the Moon — including the first woman and the first person of colour.

What permanent significance that will have is anyone’s guess. But it does mean that, after half a century, we are finally recapturing some of the wonders of human space exploration. We are once again seeing live streams from lunar orbit — not from a robotic orbiter, but from a capsule that is steered remotely by humans and will one day carry them. We are seeing the pale blue dot of Earth, in the cold depths of interplanetary space, in real time, contextualizing our fragile presence on a vulnerable planet. These might be smaller steps for humankind than they once seemed — but they are steps, nevertheless.

Lift off! Artemis Moon rocket launch kicks off new era of human exploration

Lift off! Artemis Moon rocket launch kicks off new era of human exploration

The $93-billion plan to put astronauts back on the Moon

The $93-billion plan to put astronauts back on the Moon

NASA should lead humanity’s return to the Moon

NASA should lead humanity’s return to the Moon

Nature special: 50 years since the Apollo Moon landing

Nature special: 50 years since the Apollo Moon landing

Shooting for the Moon

Shooting for the Moon