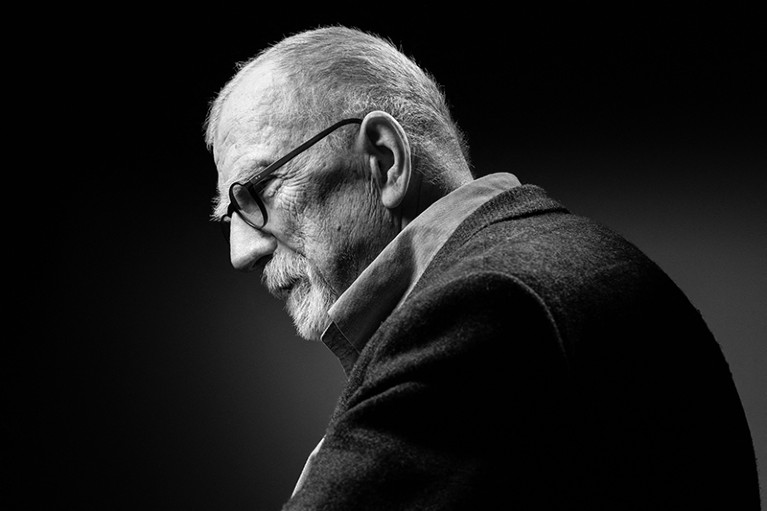

Credit: Joel Saget/AFP via Getty

Bruno Latour upended received wisdom on the nature of scientific truth. His proposition that scientific facts are constructed through networks of human and non-human actors initially outraged many. Rather than seeking objective facts, scientists were, he argued, “in the business of being convinced and convincing others”. Applying his thinking to climate change, he argued that nature could not be observed from a distance, because humanity is part of it. Yet he saw himself as a champion of science and its methods; his ideas have come to be widely accepted. The philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist has died aged 75.

Latour received the social sciences’ equivalents of the Nobel Prize: the Holberg Prize (in 2013) and the Kyoto Prize (in 2021). For a long time he was relatively unknown, and even the target of some academic hostility, in his native France. This partly reflected disciplinary rivalries. It was also consistent with Bruno’s identity as an individualist and an outsider.

He was the youngest son of a large winemaking family (the Burgundy Louis Latour, not the Bordeaux Château Latour). He took pride in the story of his great-grandfather’s triumph over the vine insect pest phylloxera, and in the consternation of his siblings when he opted to become a philosopher rather than “inherit the vines”. Imagery from winemaking informed his arguments. He asserted that, like fine wine, good ideas suffer when exported across the English Channel.

In 1976, he invited me to join him at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, where he was a visitor. He introduced me to the laboratory and its inhabitants with a beguiling sense of analytical distance. Reverently picking up a pipette, he said: “This, they believe, measures the amount of a liquid.” This anthropological perspective on everyday scientific practice was missing from contemporary accounts in the sociology of science. Our collaboration resulted in Laboratory Life (1979), the first ethnographic study of the construction of scientific facts, and Bruno’s first work in English.

How ancient DNA hit the headlines

Following undergraduate and PhD degrees in philosophy, Bruno spent most of his early career at the Paris School of Mines (1982–2006). While teaching social sciences to science and engineering students, he was part of an outstanding research group, the Centre for the Sociology of Innovation (CSI). With others, he devised Actor–Network Theory (ANT), which posited that the production of scientific knowledge and technological artefacts could be understood as interconnected alliances.

The network comprises actors as diverse as laboratory equipment, records, paper traces, material samples, citations and research grants, as well as individual scientists. An important consequence is that the strength of a scientific fact is no more (and no less) than the work needed to unpick the alliances and disassemble the network. ANT transformed social analysis and offered a new way of doing social science.

In 2006, Bruno joined the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) and developed a critique of modernity — the set of ideas and practices, arising from the Enlightenment, that the world is open to change by human intervention. If, as ANT argues, the make-up of the world depends on the interconnection of heterogeneous elements, this has consequences for some cherished dualisms: between mind and matter, the material and immaterial, human and non-human, nature and society. In particular, it challenges the assumption that the appropriate focus of social science is the activity of humans, as distinct from inert non-human matter.

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

Bruno worked on a dizzying expanse of topics: science, the law, transport systems, religion, the Brazilian rainforest, politics and the limits to growth, as well as drawing on anecdotes and everyday experiences. He pursued a form of ‘empirical philosophy’ to address these and many other pressing real-world problems, acquiring the reputation of a public intellectual. In later years, he turned his attention to the problems of the environment and climate change, on which he collaborated with artists and scientists, notably in a series of remarkable exhibitions and performance lectures.

Bruno largely avoided the absurd ‘science wars’ — the intellectual exchanges of the 1990s in which a few scientific realists mistakenly construed him as a postmodernist. But his radical reworking of accepted positions, his apparently anti-humanist levelling of the distinction between people and things, and his scepticism about the very concept of society made him a controversial figure. When he was being considered for a position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, several eminent scientists there threatened to resign.

He wrote about profound issues with a disarming lightness. His lectures and presentations, too, were full of wit, imagination and charm. At a lecture at the University of Oxford in 2003, a junior researcher dared to interrupt Bruno to point out a logical inconsistency. Bruno paused, and exclaimed: “But I am French!”, to rapturous applause. He was warm and generous in all his dealings, making a point of sitting with PhD students at conference dinners. Yet he was a man of patrician aspiration. In 2006, he withdrew from discussions about a possible position at Oxford, saying that he “wanted to do things for France”.

Bruno would repeatedly confound his critics by modifying his arguments, changing direction and finding new targets. By 2015, he was claiming of Laboratory Life: “This little book, which started as a critique of science, is now actually being used by scientists to help them in their research.”

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

How ancient DNA hit the headlines

How ancient DNA hit the headlines

Understand the real reasons reproducibility reform fails

Understand the real reasons reproducibility reform fails

The Large Human Collider

The Large Human Collider