The DART team cheers after receiving confirmation that its spacecraft had successfully collided with the asteroid moon Dimorphos.Credit: NASA/David C. Bowman

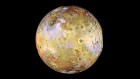

It was a crash for the ages. On 26 September, 11 million kilometres from Earth, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft met a spectacular end as it hurtled into a tiny asteroid moon named Dimorphos. This was the first test of whether humanity can alter the orbit of a space rock, by accelerating Dimorphos in its orbit.

Both Dimorphos and its parent asteroid are harmless, but NASA wanted to test whether it’s possible to deflect a dangerous space rock, should one ever head towards Earth. Researchers should know the answer relatively soon. But, at the same time, DART has shed discomforting light on the world’s faltering efforts in asteroid defence — particularly in locating the asteroids that could be dangerous.

The risk of such an errant body crashing into Earth and causing major loss of life is small, but not zero — scientists estimate that relatively large space rocks strike every few centuries to millennia. An event with catastrophic consequences — even if it is very unlikely to happen — must be taken seriously. After all, the dinosaurs died out 66 million years ago when an asteroid blasted what is now Mexico.

That’s why it’s time for NASA to take the next step to protect the planet from killer space rocks. The agency needs to fully fund the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor, a space telescope that will hunt for dangerous asteroids.

Fresh images reveal fireworks when NASA spacecraft ploughed into asteroid

As the space agency of the world’s leading spacefaring nation, NASA has ended up with the overwhelming responsibility of hunting for asteroids and saving civilization from such threats. In 1994, the US Congress instructed NASA to look for any potentially threatening asteroids that are at least 1 kilometre wide. The agency completed that task in 2010. NASA-funded scientists are now using several telescopes around the world to find smaller space rocks that are at least 140 metres across (Dimorphos measures some 170 metres in diameter). The smaller rocks are still dangerous: they could cause regional devastation. The researchers have found nearly 30,000 of them so far. But, with current resources and instrumentation, it will take three decades to finish the job.

The small — but non-zero — risk of a dangerous space rock popping up sooner means this is not good enough. NASA has been slow-walking the development of a custom-built space-based telescope to search for near-Earth objects for many years. It had given small amounts of money to a predecessor mission before embarking on the first stages of NEO Surveyor in 2019. But earlier this year, just as scientists were preparing to finalize the mission’s design, NASA proposed slashing its budget for the current fiscal year from an expected US$170 million to $40 million. That would effectively delay the telescope’s launch from 2026 to 2028, if not later.

In a rare (and welcome) moment of bipartisan agreement, Congress has indicated that it will restore some of the proposed budget cuts. But this funding would go only partway, providing around $80 million or $90 million for NEO Surveyor — not enough to keep the project moving forward effectively. The longer it takes to build the telescope, the more expensive it will be in the end.

Last month, NEO Surveyor passed a preliminary design review, an important step in confirming the mission’s viability. By the end of this year, NASA needs to decide whether it will commit to launching the telescope. In April, an expert panel on US planetary-science priorities gave NEO Surveyor a full-throated recommendation to proceed. Other nations are unlikely to step up and undertake such a mission. For the sake of the planet, it is time to support the mission whole-heartedly and get it launched.

Fresh images reveal fireworks when NASA spacecraft ploughed into asteroid

Fresh images reveal fireworks when NASA spacecraft ploughed into asteroid

This spacecraft just smashed into an asteroid in an attempt to change its path

This spacecraft just smashed into an asteroid in an attempt to change its path

NASA spacecraft will slam into asteroid in first planetary-defence test

NASA spacecraft will slam into asteroid in first planetary-defence test

Record number of asteroids seen whizzing past Earth in 2020

Record number of asteroids seen whizzing past Earth in 2020