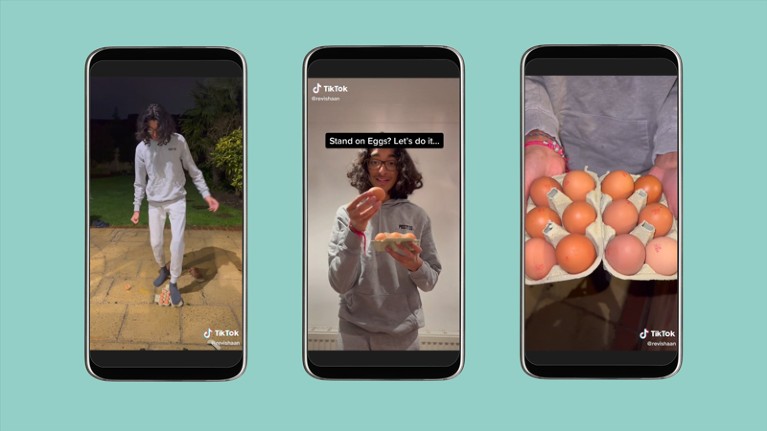

Revishaan was one of five TikTokers who took part in the first phase of the Institute of Physics Limit Less campaign.Credit: Getty, Ishaan Bhimjiyani

The Institute of Physics (IOP) wants to inspire young people who’ve never considered themselves as potential physicists. In October 2020, it launched the Limit Less campaign, which aims to encourage young people from under-represented groups to study physics at A-level, the main qualifications used by UK universities to select students for undergraduate courses. The campaign uses high-profile TikTokers to raise awareness of the subject. Ray Mitchell is head of campaign strategy at the IOP, which is based in London and represents physicists in the United Kingdom and Ireland. He explains why the institute reached out to influencers.

Tell us more about Limit Less.

The campaign aims to reach more young people with positive messages about physics, especially those who are currently under-represented. Its report, which came out in 2020, showed that many are given incorrect information about the subject by people they listen to and trust (such as parents and teachers), based on their previous experiences and their own biases. These range from “it’s boring” and “it’s not creative”, to “you need to be a lone genius like Einstein to do it”. Also, that if you’re a girl or from a working-class background or from a Black Caribbean community, that it’s not for the likes of you. The primary target of the campaign is people who influence younger people — parents, teachers, the media and influencers on social media.

What does this under-representation look like?

Collection: Diversity and scientific careers

The report showed that of young people taking physics A-level in state schools in England, around 70% come from just 30% of schools. The data around gender are particularly striking. In 2020, physics was the second most popular A-level subject for boys in England and Wales, but the 15th most popular for girls. In 2019, only 2–3% of girls chose A-level physics, compared with around 9% of boys. According to the Joint Council for Qualifications, which represents the eight largest qualifications providers in the United Kingdom, more girls got an A grade in psychology A-level than actually took physics A-level.

Among ethnic groups, young people of Black Caribbean descent are most under-represented. They make up 1.4% of pupils aged 16–19 at state schools in England, but only 0.5% of those taking physics A-level. White British young people make up 76.9% and 73.3%, respectively.

We also commissioned independent research that found significant unmet demand for physics skills, with nearly 9,000 high-duration vacancies in mid-2021. There’s also a shortage of physics teachers, with too many schools having no specialist physics teacher. England alone has an estimated shortage of around 3,500 physics teachers.

Why did you choose TikTok over other channels?

When you look at TikTok, the millions of younger people who are on it and the amount of time they spend there, it seems a natural medium for us. It doesn’t replace all the work we do in terms of science, communication and public engagement. It just adds an even bigger audience, getting across some very simple messages. With TikTok, we are using trusted ‘go-betweens’, or influencers, whose opinions are sought out and whom younger people will listen to.

How did you choose the influencers?

A good starting point in any campaign is to recognize when you don’t know something, and this was all new to us. So, we went out and invited agencies to tender and come to us with specific ideas. Once we had chosen an agency, it came back with ten or more influencers, and we had the final say. We chose five different TikTokers with different demographics. There were two women with huge followings: Shauni, with 16.7 million followers and TamzinTaber (4 million). We also picked Matthew and Ryan, a gay couple with 5.6 million followers, plus Morgan M-James (794,000) and Revishaan (187,000). Between them, they represent a good cross section of young people, and in future we plan to continue to be as inclusive as possible by using influencers from as many backgrounds as we can.

We didn’t choose the influencers solely on demographics and target groups, but also because of their average engagement rates, views per video and so on. We wanted to ensure they had that undefinable ‘fit’ with what we were setting out to do, so we reviewed their previous videos, especially those that had been branded content.

What do they do in their posts?

In their short videos, they each do the same simple and accessible experiment — demonstrating how it’s possible to stand on boxes of eggs without breaking them, and saying that it’s physics that explains this. Each of the five influencers did their own video in very different ways, using the hashtag #IOPLimitLess and saying “Physics is for everyone.” The videos were posted in the 2021 Christmas holidays because we were advised that young people were going to be glued to their phones more than ever then.

What impact has the campaign had?

We immediately started to see huge numbers of views — now it’s up to more than 750,000 — and great engagement. Shauni’s post had 13,000 likes. Plus, just under 1,000 people have gone on to look at more information on our website, which is terrific, especially because this was not our primary objective and involved some effort on their part, not just clicking a link. We’re told that an 8% engagement rate is seen as very good on TikTok and we’ve had 11%, so that’s brilliant.

How did you get on with the influencers?

I have a huge respect for them and understand their work a lot better now. I think it’s easy to dismiss their skills, but all the creativity in the videos has come from them. We gave them a very light steer on the messages that we wanted to communicate and the theme, but they all went away and did their own videos based on knowing their audiences and what works, and their own personalities. They put a lot of effort into it and a lot of thought. It looks easy because they’re really good at it.

How much did it cost?

We’re talking tens of thousands of pounds for this — low tens, rather than high tens, which I think compares very favourably with advertising and other activities to reach the same audience on the scale that we want to.

Was that the end of the social-media campaign?

No — we were also advised to use the half-term school holidays in February as a time when young people are on their devices more. So we asked the TikTokers to release videos on a new subject in the week beginning 21 February. It was another experiment that anyone could do at home, which can be explained by physics in a simple way. It involves putting a cloth over a glass of water and turning it upside down, then putting it over someone’s head. The videos are very good — again, lots of fun and lively. This phase of the campaign also added the TikToker Rhia (who has 14 million followers).

How will you evaluate the campaign’s long-term impact?

The ultimate measure of success for our campaign will be if more young people from groups under-represented in physics choose to do physics at 16 — either studying or taking on an apprenticeship, for example. This is a very specific goal, but of course it won’t happen overnight. Each year, we will be monitoring the exam data published by the governments in the United Kingdom and Ireland, to see if there are any changes — which itself is a challenge, because of the inconsistency and lack of publicly available data.

However, we can and do also measure the impact of specific activities in the campaign, and learn from them. For example, our activities during careers week involve gathering feedback from teachers and students about the usefulness of our materials and events, and how the content has affected students’ thinking about physics as a subject choice and possible career. We use this feedback to make future activities even more effective. The more we are confident that our campaign activities are ‘influencing the influencers’ around young people, the more we can be confident of their long-term positive impact.

Some physicists have criticized the campaign for not using actual researchers. What is your response to them?

Our activity on TikTok — so far — doesn’t benefit from the participation of physicists, but many other parts of the campaign do, and it’s important to look at it as a whole. In fact, a key part of the campaign is encouraging and supporting more physicists to get out there and tell families and young people about the benefits physics has provided for them. We have seen young people be very surprised, for example, when a physicist has told them that their work has taken them to exciting places around the world — chipping away at the misconception that physicists are stuck in a laboratory working on big equations on blackboards. We also want more employers to support their physicist employees in doing outreach in their communities. That is an important theme of the campaign in 2022.

Before this campaign, were you on TikTok?

No. But now, I’m on it a lot.

Why physics is still a man’s world, and how to change it

Why physics is still a man’s world, and how to change it

The school physics talk that proved more popular than Lady Gaga's boots

The school physics talk that proved more popular than Lady Gaga's boots

Thirteen tips for engaging with physicists, as told by a biologist

Thirteen tips for engaging with physicists, as told by a biologist

Twelve tips for engaging with biologists, as told by a physicist

Twelve tips for engaging with biologists, as told by a physicist