A vaccination centre for vulnerable people and those over 75 in Paris.Credit: Kiran Ridley/Getty

In January, French President Emmanuel Macron called the AstraZeneca–Oxford coronavirus vaccine “quasi-ineffective for people over 65”, on the day that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended approving it. Kate Bingham, one of the architects of the UK vaccine-procurement programme, has since called the remarks “irresponsible”, because the vaccine has been recommended by regulators for use in people of all ages.

Although some 20 million doses of the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca, based in Cambridge, UK, and the University of Oxford, UK, have been administered across Europe, a political war of words has erupted over its safety and efficacy. Such interventions risk increasing vaccine hesitancy. Communication on vaccine safety and efficacy must always be handled with extreme care.

Last week, more than 20 European countries paused the vaccine’s roll-out for a few days after a very few cases of blood clots were detected in people who had been vaccinated. These were 7 cases of clots in multiple blood vessels (disseminated intravascular coagulation) and 18 cases of clotting known as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Among the people affected, nine deaths had been recorded.

COVID vaccines and safety: what the research says

The EMA, which is based in Amsterdam, reviewed the evidence, and recommended that injections be resumed, because the benefits of vaccination overwhelmingly outweigh the risks. But it is amending information for patients and health-care professionals to mention the rare cases of clotting. The agency also says it will continue to review the risks of these conditions from the vaccine. Separately, the US Drug and Safety Monitoring Board has asked AstraZeneca to provide it with the most up-to-date efficacy data.

The regulators are acting within their remit, as they need to. The EMA assessed the evidence in response to concerns. The atmosphere is febrile as vaccines are distributed at a speed and on a scale never seen before. Researchers are rightly debating the risks and benefits of the pause, but what countries don’t need is their politicians and policymakers offering opinions on safety and efficacy in parallel to the work of independent regulators.

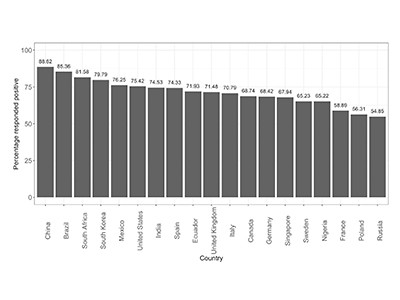

Vaccine hesitancy is of mounting concern around the world, and Europe is now experiencing its third wave of the pandemic. It’s becoming clear from research that mistrust in governments is a factor for those reluctant to be vaccinated. In a survey of 13,000 people in 19 countries carried out last June, health-policy researcher Jeffrey Lazarus at the University of Barcelona in Spain and his colleagues found1 that people with little trust in government were less likely than others to say that they would get a vaccine.

Mistrust in governments comes in many forms. In France, for example, vaccine hesitancy is associated with public controversies involving the government and the pharmaceutical industry2. Researchers say that a loss of trust coincided with the government overestimating the need for vaccines against H1N1 swine influenza in 2009. A study3 published last year reported that people who do not vote for the main French parties of government were less likely to say that they would get the COVID-19 vaccine.

A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine

A more severe example of the impact that government actions can have on public perception of vaccines stems from a campaign by the US Central Intelligence Agency. In 2011, Osama bin Laden, leader of the Islamist terrorist group al-Qaeda, was thought to be hiding in the city of Abbottabad in northern Pakistan. To confirm this, the CIA set up a programme in which staff vaccinated children against hepatitis B to gain access to people’s homes4. This violated the trust between people and their health-care professionals, and set back vaccination efforts in Pakistan.

The knowledge that trust in governments is falling and that mistrust in government and institutions fuels vaccine hesitancy has also helped researchers propose interventions to boost engagement. Authorities worldwide are employing more-trusted individuals, such as people from health care, research, trusted religious and community leaders, and celebrities from the arts, entertainment and sport, to encourage vaccine take-up. And it is essential to provide vaccination facilities at the heart of affected communities so people do not have to travel far, physically or emotionally, to receive their vaccines.

In all countries, vaccines are approved through independent regulatory processes. Crucially, these decisions are based on evidence from studies, independently of politicians and policymakers. When politicians speak out of step, they potentially undermine those processes. And when a regulatory process is undermined, that produces a risk to vaccine confidence. Arguments are normal in political discourse, but a pandemic is not the time for an adversarial style of communication over vaccines. If politicians and policymakers do not know that their words and actions are a reason for vaccine hesitancy, then their scientific advisers must make them aware of this.

The world must emerge from this pandemic with as many people as possible vaccinated. To achieve that, people in politics must leave judgements on vaccination safety and efficacy to the independent experts that they — and their publics — have entrusted with making these decisions.

COVID vaccines and safety: what the research says

COVID vaccines and safety: what the research says

A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine

A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine

Vaccine hesitancy and coercion: all eyes on France

Vaccine hesitancy and coercion: all eyes on France