Many cities in China, such as Xi’an (pictured), have experienced rapid growth in the past few decades.Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

On 28 January 2020, a team of Chinese conservation scientists distributed a questionnaire across social-media platforms, asking Chinese citizens how they felt about proposed legislation that would ban the consumption and trade of wildlife in the country.

It was an apposite moment: the questionnaire hit social-media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo just days after China had been forced to close its major cities to prevent the spread of a disease that scientists suspected was transferred to humans from an animal species at a market in Wuhan.

More than 90% of the 74,070 respondents were in favour of a complete ban on wildlife trade — and, a month later, the central government came to the same conclusion and legislated to that effect. Researchers are increasingly studying the impact of these policies, and the country’s biodiversity. But big questions remain about whether China will deliver on its growing list of environmental commitments.

Bin Zhao, an ecologist at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, says that, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, people in urban areas have been paying more attention to biodiversity than ever before. “People realized that contact with wild animals could lead to an outbreak of an epidemic, even in urban areas. This not only enhanced people’s understanding of biodiversity, but also promoted the idea that wildlife-protection law needed to be improved,” says Zhao.

It came at a time when China was already committed to changing its approach to ecological protection, he says. In 2018, China amended its constitution to include the goal of becoming an ‘ecological civilization’. In the words of Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2017, economic development could no longer be at the expense of the environment.

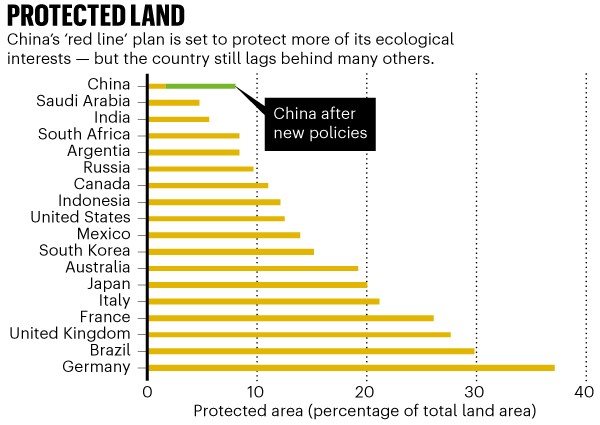

Multiple environmentally friendly policies have already been announced, such as the introduction of an ‘ecological red line’ policy to protect more of the Chinese mainland from development (see ‘Protected land’); a new network of national parks; stricter supervision of conservation; and a streamlining of environmental-oversight agencies — all to meet a government target of making the country’s environment ‘beautiful’ by 2035.

Sources: UN/Xinhua/OECD

Big cities, few controls

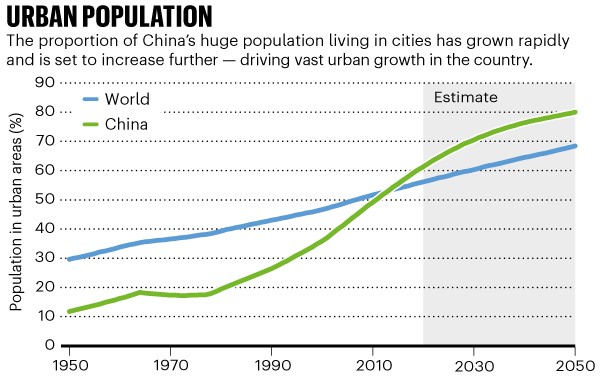

In 1950, about only 13% of China’s population lived in cities. But since the 1980s, the country’s cities have grown rapidly as the engines of its economic growth (see ‘Urban population’). Millions left homes in rural areas to forge more prosperous lives in growing and newly built cities. Government policies, aimed at bolstering the economy, helped to encourage close to two-thirds of China’s population to move to these new urban areas, and the nation continues to have one of the world’s fastest growing urban populations. This has put intense pressure on the country’s ecology.

Sources: UN/Xinhua/OECD

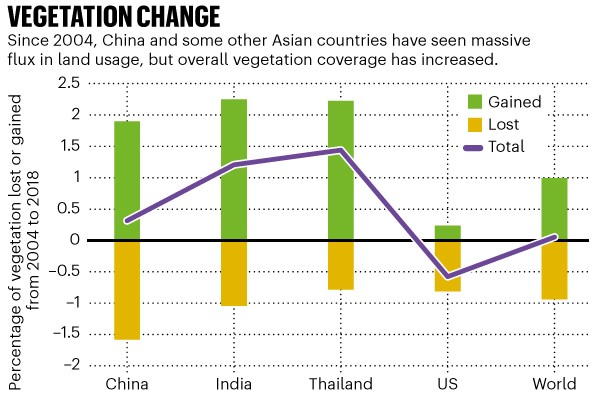

“From an economic perspective, our ecosystems and environment have historically been considered to be worthless,” says Zhao. China’s natural resources, such as its wetlands, forests and water sources, haven’t received the same level of care from authorities as targets for economic growth, he says (see ‘Vegetation change’).

Sources: UN/Xinhua/OECD

As urban areas grow, there are direct and indirect impacts on ecological systems, according to Rob McDonald, who researches the impact and dependencies of cities on the natural world at The Nature Conservancy in Washington DC.

Land is repurposed for development, and natural resources are needed to construct buildings and provide food and water for city dwellers, he says. These changes can lead to environmental problems, such as water and air pollution, insufficient water availability and deforestation much farther afield than in urban areas themselves.

China’s government has been open about its commitment to tackling these problems, says Alice Hughes, a zoologist at the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden in Menglun town, China. In May 2021, China will host the fifteenth United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, also known as COP 15, in Kunming, where 200 countries will meet to sign off on a legally binding set of global targets to protect the world’s biodiversity. The country has already contributed to some broader environmental targets, including being carbon neutral by 2060.

China has had some success, most notably in reducing air pollution. For example, in 2017, the amount of fine particulate matter in Beijing’s air dropped by just under 40% from the level in 2013, the year when national targets were launched.

But at a press conference to discuss China’s progress on ecological and environmental protection, Cui Shuhong, an official at the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, said the country has much more to do to alleviate the fundamental pressures placed on its natural resources by economic development.

Zhengguang Zhu, an environmental officer at China’s National Marine Environmental Monitoring Center, is familiar with preparations for COP 15: there are multiple working groups operating within the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, which are each responsible for different aspects of the event, from logistics to setting targets for improvements to China’s environment.

Live turtles on display at a wildlife market in Shanghai, China, in August 2020. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government issued a policy banning wildlife trade for food, but trade of exotic animals as pets still continues.Credit: Ales Plavevski/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

These working groups ask China’s public bodies, such as the ministry of agriculture, to offer their opinions on what the country feels should be included in the final roadmap for the coming decade.

“I think the meeting will show that China has done its homework and is willing to be a good host. But leadership is not just about hospitality. It’s about having an ambitious framework that enables change, and I think we’ve got a long way to go before that happens,” says Zhu.

Behaviour change

Conservation researcher Tien Ming Lee, based at the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, says scientists and politicians are currently focused on finding better ways to protect Chinese ecosystems while continuing the country’s urban economic growth.

His research team works across a range of projects, all focused on finding ways to prompt people to act differently and sustainably. For example, he is currently part of a 4-year, €10-million (US$12 million) project, mainly funded by the European Union, called Partners against Wildlife Crime. The project, which began in January 2019, hopes to disrupt the illicit supply chains through which exotic animals and plants, specifically tigers (Panthera tigris), Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), Siamese rosewood (Dalbergia cochinchinensis) and freshwater turtles, are traded throughout Cambodia, China, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

As part of this project, Lee’s team and Lishu Li at the Wildlife Conservation Society China Counter Wildlife Trafficking Program are developing marketing materials to change the buying habits of urban Chinese consumers by attempting to dissuade them from illegal acts, such as buying tiger bone or elephant skin online for jewellery and traditional medicine, or keeping endangered freshwater turtles as pets. Lee says the materials have been developed with behavioural-science techniques: they aim to appeal to consumers’ desire to be seen to act in a conscientious manner.

Police patrol the wetlands of the Yellow River Estuary ecotourism area near Dongying City, China.Credit: Costfoto/Barcroft Media via Getty

Lee has also been part of a research project that looked at how trade agreements that stem from the country’s international Belt and Road economic initiative, an infrastructure project that aims to link trade across Europe, Asia and Africa to China, could lead to a greater demand for traditional Chinese medicine across the world. The plant, animal and fungal products used in these practises are often sourced from the wild, which might exacerbate the illegal and unsustainable trade of those species, he says.

His research, a collaboration with Amy Hinsley, a conservation biologist at the University of Oxford, UK, concluded that there was a clear, urgent need for China to introduce carefully managed supply chains and ensure that rural farmers have resources for sustainable farming.

During her four-decade career, Lu Zhi, a conservation biologist at Peking University in Beijing, has seen a shift in her field’s focus. It moved from observing animals in their natural habitats and coming up with ways to protect them from human activity to observing human behaviour: studying what can be done to make people’s lives more ecologically sustainable.

In 2017, Zhi’s Shanshui Conservation Center, a non-governmental organization she founded in 2007 to develop community-based conservation projects, began working with herdsmen in Qinghai province on the Tibetan Plateau. The team wanted to help them to develop livelihoods from conservation activities in an underdeveloped, highly biodiverse area of China. The villagers learnt how to patrol and monitor wildlife, and how to act as guides for tourists interested in animal watching — including for the elusive and endangered snow leopard (Panthera uncia). Similar projects have been rolled out in 42 villages in western China.

Zhi admits that such small projects are certainly not enough to bring the paradigm shift needed to safeguard the country’s vulnerable ecosystems. Government intervention has proved to be effective in tackling the larger issues, such as air and water pollution, she says. But “it’s not fair to ask people in rural areas not to develop their lives for the sake of wildlife, while others live in prosperous cities. We need alternative solutions.”

Seeing biodiversity from a Chinese perspective

Seeing biodiversity from a Chinese perspective

How to limit the ecological costs of urbanization in China

How to limit the ecological costs of urbanization in China