GHANA: We are building capacity

Gordon Awandare

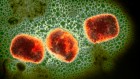

In Ghana, the pandemic has not been severe, and deaths have been very low compared with those in other parts of the world. Our group was among the first to sequence SARS-CoV-2 in Africa. We achieved this because we are building capacity for next-generation sequencing for other research purposes, including malaria-parasite genomics.

When the pandemic hit, we quickly redirected those resources and personnel to work on sequencing the virus because we felt it was important to be able to track the transmission and evolution of the virus locally. This was challenging because we did not have all the necessary reagents and had to improvise. We also had to obtain some reagent components from various collaborators in the United Kingdom. Many exciting projects have had to be put on hold. Students’ research has been delayed, and they’ve been unable to complete their PhD or master’s programmes on schedule.

In responding to pandemics, leadership has to be decisive. For example, masks should have been mandated early on. And lockdowns would have worked better had they been targeted, imposed quickly and enforced strictly.

In the big picture, African governments need to build scientific capacity sustainably rather than resorting to firefighting only when a pandemic hits. We should be preparing for the next pandemic as soon as this one ends.

BELGIUM: We were stymied by politics

Emmanuel André

In recent decades, Belgium has disrupted the continuity between prevention and curative care, thereby dismantling a health system that was built over centuries. As a consequence, we entered this pandemic unprepared, with no protective equipment in stock and a scarcity of doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians. This compounded other, less easily preventable vulnerabilities: a dense, ageing population, and one that is highly mobile both inside and beyond the borders.

Crisis management was further hampered by Belgium’s complex institutional system. This meant that nine health ministers had to respond to six separate governments, each having a different balance of political parties. Despite national elections taking place in May 2019, a federal government was not set up until October 2020. This situation seeded an uncoordinated constellation of ‘advisory committees’ with overlapping prerogatives and variable lifetimes. The composition of these committees was subject to politicians’ whims. In early September, when signs of the second wave became obvious, virologists were partly replaced in the most influential advisory organ by a lobbyist and a former chief executive of the postal services.

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

For months, no political leader took responsibility for putting in place a long-term plan that would include clear thresholds for implementing disease control measures or for ensuring that compensation would be fairly and promptly distributed to vulnerable people and to the economic sector affected most.

The media placed scientists at the forefront of the crisis; public opinion praised iconic scientists to the skies. Meanwhile, some politicians pushed for an early easing of unpopular disease-control measures to gain public approval and in the hope of minimizing their economic impact. But epidemiological risk-taking ultimately led to prolonged lockdown and extra damage to an economy that requires stability and consumer confidence.

Next year must be different. We need to be consistent and make sure that hopes do not become deceptions. There will be vaccine hesitancy, unforeseen difficulties and unequal access. Increased testing capacity will not stop people becoming infected unless it is coordinated with a fully functional infection control and tracing system. All interventions should recognize that the most fragile people are also the ones most affected by this pandemic.

The scientific community should continue transgressing the boundaries between disciplines and countries to offer society more knowledge, more evidence and better policies, so as to finally alleviate the ravages of this pandemic. We should make sure that exiting this complex crisis leaves no one behind — and that our shaken world becomes more equal, collaborative and efficient in tackling worldwide challenges.

COSTA RICA: We fought misinformation

Eugenia Corrales-Aguilar

When the pandemic began, politicians and journalists in Costa Rica started talking to me because I am a virologist and had worked with bats and coronavirus. I thought that maybe we would be able to control this virus with the same public-health measures that we used for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003. We were naive.

One of the things that’s been really different this time has been the response of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States. We’d always looked to it for guidance on everything to do with infectious disease — until now. The lack of unpoliticized, evidence-based information from the CDC has been a challenge throughout this outbreak.

Another challenge has been the tsunami of information. I’ve never studied so much in my life, not even for my PhD. And this real-time scientific information has to be translated and applied almost immediately.

2020 beyond COVID: the other science events that shaped the year

What is really difficult is knowing how to communicate all this to non-scientists. There’s so much nonsense and disinformation. I think vaccine communication — reaching people who do not want to understand that vaccines are game-changers — will take up much of my time for next year.

I’ve also been attacked: “What do you know? You’re just a young lady that doesn’t care about my restaurant that’s closing,” or “Viruses do not exist.” But for every 50 people who think like that, there are hundreds or thousands who are thankful, who are really eager to understand.

My biggest success? Women are still under-represented in decision-making committees in Costa Rica, and I’m there giving evidence-based information to the national ministry of health and being heard. That is an example for younger generations.

TAIWAN: We learnt from SARS

Chien-jen Chen

I wish I’d been able to urge the World Health Organization (WHO), China and other authorities to take prompt actions to stop COVID-19 progressing from a local outbreak into a catastrophic pandemic. Taiwan tried, but failed, to join the 23 January emergency meeting held by the WHO, which did not announce COVID-19 as a public-health emergency of international concern for a further 10 days.

It has been my privilege to work alongside my fellow citizens in Taiwan to combat COVID-19. Almost everyone in Taiwan complied with guidelines and regulations for epidemic control. Only around 1,000 of around 400,000 people isolated or quarantined at home violated the restriction. The rest sacrificed 14 days of freedom to let 23 million people live, work and go to school normally. We have been COVID-free now since 13 April.

Key elements of Taiwan’s success include prudent action, rapid response (we took action on 31 December) and early deployment of control measures, together with transparency and public trust with solidarity. We did not need to implement city lockdowns or mass screening. Instead, we applied information technology and artificial intelligence to carry out precision disaster prevention and mitigation. These efforts included border control and quarantine, social distancing, contact tracing, precision testing, hospital infection control, and rationing and mass production of face masks and other personal protective equipment. The government also provided financial support to low-income families and affected industries, and economic stimulus vouchers to every citizen.

The 2003 SARS pandemic taught us the effectiveness and efficiency of measures such as border control, mandatory case reporting and isolation treatment, as well as contact tracing, testing and isolation. I’d also like to stress the importance of professionalism and political neutrality, which earn public trust and compliance with epidemic control measures.

Disinfecting Bolivia’s streets during lockdown in April.Credit: Aizar Raldes/AFP/Getty

BOLIVIA: Against all odds we did not fail

Mohammed A. Mostajo-Radji

Every international agency we spoke to predicted that Bolivia would be hit harder by COVID than most nations. It has one of the worst health-care systems in the world, with several regions refusing to share information with the central government. Our neighbours, including Brazil, Peru, Argentina and Chile, have all been badly affected by the pandemic.

The first meeting between the country’s strategic response team and the WHO, in early March, showed us that Bolivia had not yet recovered from a catastrophic dengue epidemic — and, for the first time in more than 20 years, measles had reappeared. The country’s three public molecular-testing laboratories were already saturated.

So on 17 March, we implemented one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. This gave us time to take stock of the health-care system. Supplies were scarce. And because much of the population lives at high altitude, where atmospheric pressure is low, most of the available equipment was of no use. It was therefore essential to have our own scientific advisory committee and to connect with specialists from across the world to receive real-time feedback and updates. Science diplomacy has never been so important: it allowed us to access donations of equipment and vaccines, coordinate the rapid transport of medications and design a shared response strategy with other countries.

In the months leading up to the general elections in October, COVID-19 became highly politicized. From protesters impeding the movement of ambulances and oxygen tanks, to technicians stealing testing reagents to sell on the black market, the battle became more difficult every day. Internally, I fought ageism from members of the cabinet and the armed forces who refused to take advice from someone less than half their age.

Still, Bolivia has one of the lowest infection rates in the Americas. I look back on all the discussions, and all the people whose hard work became vital during these months, and think “against all odds, we did not fail”.

LITHUANIA: We feel we’re still fighting a war

Ligita Jancoriene

Working in this pandemic feels like war — or exile. As we strive to make sense of the battle against COVID-19, my colleagues and I in Lithuania, at Vilnius University Hospital, have started comparing cataclysms that our families have experienced — from military conflicts to the mass deportations carried out by the Soviet Union. We physicians face a constant struggle with an invisible enemy, anxiety about the future, daily encounters with dying patients, and unbearable strain, fatigue and overwork.

In the hospital, the first challenge was redeploying medical staff to work with people with COVID-19, and setting up new units to treat them. Everyone had to leave their comfort zone, and it was not easy. Some staff refused; others volunteered. Later, during the second wave in early October, treatment units were opened in regional, non-university hospitals. There, staff resistance was particularly high — possibly out of fear or lack of knowledge.

So we invited regional doctors to our virtual meetings, case discussions and internal seminars. They became members of our COVID team. A sense of collegiality and teamwork — that no one was alone on the battlefield — helped medical staff on the pandemic front to keep going.

There was chaos at the beginning. Decisions were made on the fly, and orders changed frequently. I have been involved in two expert groups advising the government, but there was no dedicated team for managing the pandemic. Medical institutions often had to make immediate decisions on their own. Medical staff working with people with COVID-19 were promised extra pay, which was repeatedly delayed by the ministry of health. Greater trust in professionals, and decision-making on a horizontal basis rather than a hierarchical one, would have speeded the response — and boosted trust in government.

In treatment and care facilities, sometimes all the staff, and nearly all the patients, became infected within a few days of the first case. In such instances, emergency assistance was paralysed, and whole departments had to close temporarily. This caused complete despair.

As we face future waves, we need to strengthen resources for health-care workers on the front lines. Clear guidelines must be prepared on how to manage COVID-19 infection in a regional hospital or nursing home, rather than every patient being referred as quickly as possible to a larger centre. Early on, health authorities focused on university hospitals equipped with personal protective gear and other specialized equipment. Now, there are simply too many patients, and each facility must be prepared to diagnose and treat those who are infected. Otherwise, we risk continuing to lose this war.

CANADA: Science guided our decisions

Mona Nemer

In 2017, a few weeks after my appointment to the newly created position of Canada’s chief science adviser, the question about my role in national emergencies arose. I looked internationally for advice. Starting with consultations with my UK counterpart and culminating last year with joint tabletop simulations with the United Kingdom and the United States — including one of a pandemic — these exercises provided guidance on how science can assist government in times of crisis. The connections developed then have proved invaluable this year, because my international counterparts and I met regularly throughout 2020 to share data and best practices on virus spread, public-health measures, diagnostics development and roll out, and therapeutics and vaccine trials.

Soon after the pandemic arrived in Canada in late January, my staff and I assembled several multidisciplinary scientific advisory groups to help me provide up-to-date COVID-19 advice to the prime minister and cabinet. As we focused on areas ranging from vaccines and aerosol transmission to children and long-term care, researchers mobilized to share their findings and advice quickly and openly. As a result, science guided decision-making in real time like I have never seen before. The contrast with some other parts of the Americas has been striking.

It has been gratifying to witness public appreciation of, and government interest in, science. This has provided welcome encouragement in such stressful and uncertain times. The sheer objectivity of science can go a long way in a crisis, especially when response is hampered by inaccessibility to data, reagents and personal protective equipment.

To take on future existential threats, nations need to strengthen their science advisory systems locally and globally, and build public trust in research. Understanding the scientific method empowers people to question information sources and to deal with uncertainty, which ultimately helps to minimize the spread of misinformation. Researchers can help — by openly sharing their knowledge and inspiration, and by helping to rebuild societies in a way that puts evidence at the centre of all decisions.

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

2020 beyond COVID: the other science events that shaped the year

2020 beyond COVID: the other science events that shaped the year

Nature’s 10: ten people who helped shape science in 2020

Nature’s 10: ten people who helped shape science in 2020

The best science images of 2020

The best science images of 2020