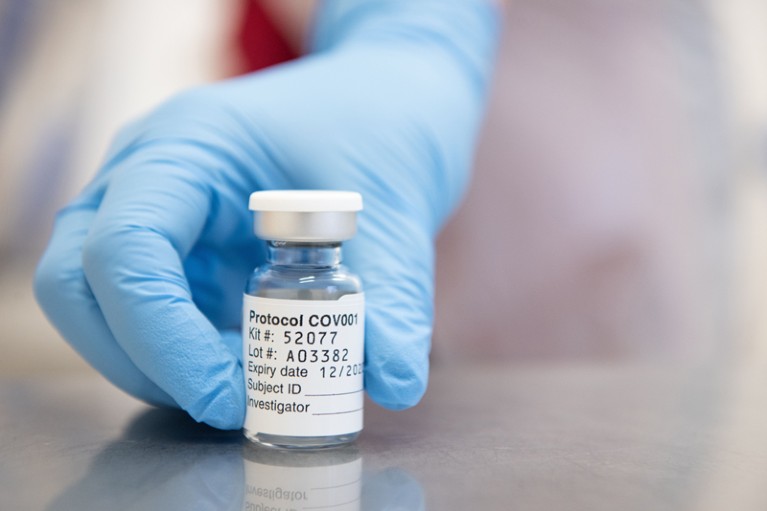

The University of Oxford and Astra Zeneca have pledged that their COVID vaccine (pictured) will always be available at cost to low and middle income countries. Other develpers must make the same commitment.Credit: Oxford Univ./John Cairns/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

A year on from the first known case of COVID-19, the world has been hungry for good news. This month, vaccine makers have provided welcome nourishment.

Large clinical trials of four vaccine candidates are showing remarkable promise, with three exceeding 90% efficacy — an unexpectedly high rate — according to results released so far. None reported worrying safety signals and one has shown promise in older adults, a demographic that is particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 but which sometimes responds less well to vaccines.

Early studies had shown that these candidate vaccines could stimulate an immune response. The latest trials show that this immune response can protect people against COVID-19 — a major achievement. Vaccine development is fraught with possibilities for failure, and even the most ardent optimist might not have expected to have a highly effective vaccine against a new virus less than a year after its genome was sequenced.

But there is still a vast amount of work for researchers and clinicians to do. First, they need to determine how well the vaccines work in people who are at high risk of COVID-19, including older individuals, people with obesity and those with diabetes. Second, it isn’t clear how well some of the vaccines protect against severe COVID-19. Third, it is also not clear to what extent the vaccines prevent those who have been vaccinated from passing the virus on to others.

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

At the same time, researchers and policymakers must consider how to deal with challenges not related to the vaccine candidates themselves. These include vaccine hesitancy; weariness with current public-health restrictions; and the staggering logistics of vaccinating the world population. Although the finishing line seems to be in sight, there is still much difficult terrain to cross.

Some people are understandably concerned that the speed of both scientific review and vaccine regulation could compromise safety — despite vaccine developers’ and regulators’ assurances to the contrary. To build confidence in vaccination, it’s important that regulators, companies and their research partners keep promises they have made to ensure transparency, publish data and engage with open discussion of those data as they arrive.

The US Food and Drug Administration, for example, has pledged to hold a public meeting of its external advisers in early December to discuss the data before issuing an emergency use authorization to distribute a vaccine. This kind of transparency — and the option for open airing of concerns about data, should there be any — is much needed. It stands in contrast to the agency’s earlier, opaque granting of authorizations for COVID-19 treatments.

Why emergency COVID-19 vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists:

Most vaccine teams and drug regulators have stated their commitment to data transparency. But much of what we know about the latest vaccine trials has been communicated through press releases and media interviews, rather than through research papers that have been subject to independent peer review.

Such speed of communication is necessary in an emergency. But more-complete data should not be held back, and the teams involved must be prepared to provide access to all relevant data as soon as this is practically possible, to allow others to scrutinize their findings and test their claims. It is important that companies continue to release their data as analyses are completed, and release preprint papers of completed studies, so that the work can be discussed quickly.

Regulators should also share their data and analyses with regulatory bodies in other countries, to speed up approval decisions around the world. And regulators and vaccine makers must remember that vaccines will be less effective if people refuse inoculation because of vaccine hesitancy.

It’s also crucial that the current public-health measures are not relaxed. The coming holiday season in some countries could trigger outbreaks as people rush to see long-missed family and friends. Vigilance is still important — perhaps even more so — as people see a welcome light at the end of the pandemic tunnel.

Vaccine distribution poses another daunting challenge, and is accompanied by questions such as how much it will cost and who will pay for it. One of the vaccines that has shown success in late-stage trials was developed by researchers at the University of Oxford, UK, and the pharmaceutical firm AstraZeneca in Cambridge, UK. This vaccine can be stored in a normal refrigerator, which makes rapid distribution more feasible than it would be for the vaccine developed by Pfizer in New York City and BioNTech in Mainz, Germany — which might be more effective than the Oxford vaccine, but needs to be stored at temperatures below −70 °C.

Importantly, AstraZeneca and Oxford have also pledged to provide their vaccine at cost price to all during the pandemic, and to maintain this price for low- and middle-income countries after the pandemic, when a vaccine will still be needed in case of future outbreaks. But, as Nature went to press, neither Pfizer nor Moderna, a drug company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which has a similarly promising vaccine candidate, had committed to keeping prices down once the current pandemic is over. They need to change this stance.

A number of countries — most of them wealthy — have already pre-ordered nearly four billion vaccine doses and have options for a further 5 billion, at the current prices. COVAX, a global alliance seeking to ensure that low- and middle-income countries get adequate vaccine provision, has been able to secure vaccines for only around 250 million people — far below what is needed. Once prices start to increase, the poorest countries will be even less able to pay than they are now.

Not making the vaccine affordable for these nations would be morally wrong. It would also be short-sighted, because, as infectious-disease researchers often say, an outbreak anywhere is an outbreak everywhere.

Why emergency COVID-19 vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists:

Why emergency COVID-19 vaccine approvals pose a dilemma for scientists:

COVID vaccine excitement builds as Moderna reports third positive result

COVID vaccine excitement builds as Moderna reports third positive result

What Pfizer’s landmark COVID vaccine results mean for the pandemic

What Pfizer’s landmark COVID vaccine results mean for the pandemic

Russia announces positive COVID-vaccine results from controversial trial

Russia announces positive COVID-vaccine results from controversial trial

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency