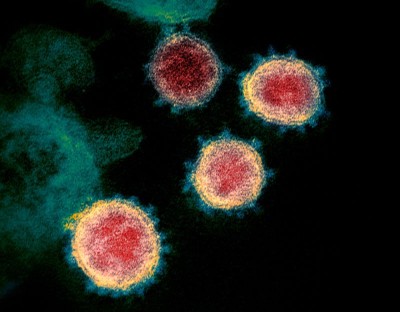

Migrant workers living in dormitories in Singapore were initially overlooked for coronavirus testing.Credit: Edgar Su/Reuters

Respiratory pathogens spread like wildfire when people are in close contact. So it’s little wonder that almost all of the 150 biggest coronavirus outbreaks in the United States have been in prisons, nursing homes, veterans’ homes, psychiatric hospitals, meat-packing plants and homeless shelters, where people live or work side by side.

The phenomenon can be seen worldwide. Singapore seemed to have almost contained its epidemic until it became clear that the virus had been spreading undetected among migrant workers living in overcrowded dormitories. Across Europe, homes for elderly people are among the worst hit. In Canada, 80% of reported deaths from COVID-19 have been in care homes.

Health officials are still failing to contain COVID-19 in shared spaces such as these because of the difficulties in achieving physical distancing. Measures, such as working from home, that protect healthier, wealthier and freer individuals, are often impossible to achieve for those whose jobs or accommodation make it impossible to self-isolate. Worse, there is little evidence to back up current policies intended to keep residents of communal spaces safe — or to support the implementation of new ones.

Evidence-based strategies are urgently needed to prevent the spread of infection in shared settings, and to detect cases early. Researchers are ready to answer this call. But policymakers and health officials must first prioritize this research, and report data on caseloads and deaths so that epidemiologists can work out, in detail, what is going wrong. Most urgently, they must make regular testing available for high-risk groups, so that responders can intervene when cases first arise.

Passing the test

In many countries, testing tends to be limited to people with symptoms such as a fever or severe cough, even though it is now well established that infected individuals without symptoms can spread the disease. Asymptomatic cases can be particularly dangerous in communal spaces, where infections spread fast. In early April, for example, researchers testing people in a homeless shelter in Boston, Massachusetts, found that almost 90% of 147 people infected with the coronavirus did not have identifiable symptoms1.

Analyses of outbreaks in US nursing homes and in prisons have found that more than half of infected residents and staff didn’t show obvious symptoms at the time of testing. Some epidemiologists, geneticists and social scientists are rightly urging policymakers to change the testing criteria so that people in communal settings are tested regularly, regardless of whether they have symptoms.

‘Distancing is impossible’: refugee camps race to avert coronavirus catastrophe

With more data, epidemiologists would be able to evaluate and compare various interventions to see which work best. For example, are face masks preventing transmission in homeless shelters and nursing homes? How effective is the practice of positioning shelter beds two metres apart? Would it be safer for homeless people to be accommodated outdoors, in tents, if single-occupancy accommodation isn’t available?

In addition, by sequencing the viruses spreading in a facility, researchers can determine how often people are introducing viruses from outside, and to what extent infections are being amplified in communities. And full cost analyses will help policymakers to compare the total costs of different solutions. Something that seems expensive upfront might, over time, result in lower overall costs once other expenses, such as hospital stays, are factored in.

In the United States, which still has the world’s highest number of confirmed deaths from COVID-19, scientists are ready to do more. Several academic labs say they can run thousands more tests than they are currently processing, and some have developed easier-to-deploy tests. For example, on 8 May, the US Food and Drug Administration permitted the emergency use of a test based on the gene-editing tool CRISPR that can be processed using less-sophisticated equipment than is required for many other tests.

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

But, for researchers to be more involved, they must be integrated into state-wide testing strategies that link them to health departments. And these agencies must, in turn, be prepared to respond to positive diagnoses.

At the moment, that is not a given. Alarmingly, some researchers have told Nature that officials are reluctant to survey people in communal spaces, because infected individuals will then need to be isolated, and their contacts potentially tested and quarantined, too. This could, in turn, mean providing single-occupancy housing units, or paying wages to quarantined essential workers — such as employees of meat-packing plants, or those working in prisons and care homes — if they cannot otherwise afford to take time off. These are undoubtedly difficult and expensive interventions, but ignoring the problem will not make it go away.

Wanted: accurate reporting

A lack of transparency is another obstacle to epidemiological analyses. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30% of jurisdictions aren’t reporting COVID-19 cases in prisons as a separate, identifiable category. Some jails are reporting outbreaks as a single event, rather than listing the number of cases. And many state public-health departments aren’t reporting infections and deaths among residents of homeless shelters and nursing homes. An outbreak at one nursing home in New Jersey was discovered only when police found 17 dead bodies piled up inside.

This cannot continue. Facilities should report what’s happening within their walls, and states should make anonymized data available quickly.

Coronavirus and COVID-19: Keep up to date

Some cities provide a model for others to follow. In Seattle, Washington — where the first US COVID-19 outbreak was detected — the public-health department has an online dashboard devoted to reporting daily cases and deaths in care homes. The city’s partnership between these facilities, researchers and the public-health department helped to reduce new COVID-19 cases in care homes from 748 in March to 72 in the first 2 weeks of May.

The lack of action elsewhere is an outrage. It isn’t getting the attention it deserves because the people who are most affected are those least able to make their voices heard. Those who are poor, from minority communities, elderly, incarcerated, chronically ill or homeless are among the most marginalized in society. Their needs have been ignored in part because they have less access to policymakers. But they should not need to make their case — those in power should already be paying attention.

Researchers, however, can do their part. They understand the need to curb this pandemic among the most vulnerable people, and must make sure they work with these groups to study the pandemic and to analyse and highlight its devastating impacts. Policymakers must act on what they find. Until countries beat this disease in the places hit hardest, they won’t be able to beat it at all.

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

‘Distancing is impossible’: refugee camps race to avert coronavirus catastrophe

‘Distancing is impossible’: refugee camps race to avert coronavirus catastrophe

Thousands of coronavirus tests are going unused in US labs

Thousands of coronavirus tests are going unused in US labs

Coronavirus and COVID-19: Keep up to date

Coronavirus and COVID-19: Keep up to date