To get all children finishing secondary school, local- and regional-level education data need to be tracked systematically.Credit: Jake Lyell/Alamy

How can we ensure that every child gets a good education? Achieving quality schooling for all is one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But one of the largest studies of its kind confirms that countries are some way from ensuring a school place for about 260 million children currently not attending school.

In a paper in Nature, a team led by Emmanuela Gakidou, who studies health metrics at the University of Washington in Seattle, reports an analysis of education data from 195 countries and territories for the period from 1970 to 2018 (J. Friedman et al. Nature 580, 636–639; 2020). From this, the authors built a model to forecast what the picture would look like in 2030 — the year by which countries agreed to meet all 17 SDGs and their associated targets.

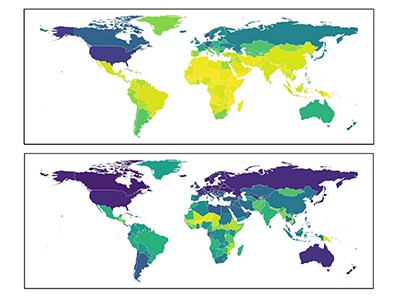

Although almost 90% of children are expected to be completing primary school by 2030, only 61% of young adults (aged 25–29) will have finished secondary education. (Moreover, the modelling was done before the COVID-19 pandemic, which is preventing many children from attending school.) If all of the targets for the education SDG are to be met, all young people need to complete both primary and secondary education — and this should be free of charge.

Read the paper: Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets

Although the education SDG might not be met, the overall trend has been in the right direction. In 1970, just 50% of 25–29-year-olds had completed primary school. That had risen to 83% by 2018, and is projected to reach 89% by 2030.

Similarly, in 1970, only about 20% of the 25–29 age cohort had finished secondary school. And in the countries of North Africa and the Middle East, just 7% had reached this milestone. By 2030, the researchers predict, around 75% of the same age cohort in these countries will have completed secondary schooling.

Attainment of tertiary education — defined as 15 or more years of education — has also improved around the world, with some of the largest gains again occurring in North Africa and the Middle East. But even in the world’s best-performing regions, the team predicts that just half of young people will be completing tertiary education by 2030.

What needs to be done so that more children can receive a full education? A more concerted push is required, especially from decision makers, and this push needs to be backed by more-precise data that build on existing knowledge. We already know, for example, that on a global level, girls are less likely than boys to complete their schooling — although this gender gap has nearly closed, which will enable more countries to make progress in the SDG for gender equality. We also know that children living in some rural areas are less likely than those in urban regions to progress to secondary education, or even finish primary school.

At the same time, we know which groups of children are less likely to enter school at all, or to progress from primary to higher levels of education. In general, it is those whose household incomes are low, which sometimes means children have to work to contribute to the household budget. Other children affected include those with disabilities, those in regions experiencing conflict and those belonging to minority groups. Disadvantage in any form tends to hold children back. Furthermore, in many countries, children are not at school because there are not enough publicly funded schools of sufficient quality.

Tracking inequalities in education around the globe

But we also need data on these factors at the level of villages, towns, cities and districts, and they need to be tracked systematically so that progress can be monitored, especially in low-income countries. Such data will shine a light on which groups need the most help, allowing educational authorities — and funders — to target their efforts.

Better data must also be collected on educational achievements, known as learning outcomes. Such data are patchy and difficult to compare across countries, because there is no agreed international standard. Although in some countries, children completing primary school are expected to be able to read to a set standard, in many parts of the world they are not. The World Bank is working with the UN children’s fund, UNICEF, to create standardized assessments for learning outcomes and — along with other organizations — is calling for these to be part of the drive to achieve the SDG for education.

How data have made a difference

Data have already helped to achieve the gains we are seeing in primary education, but these gains came out of a strong desire to effect change. Twenty years ago, 83% of children were enrolled in primary education. UN member states considered this unacceptable. They collected relevant national and local data, and discovered that the reasons for low attendance included malnutrition and poor provision for children in rural areas. Decision makers responded with measures such as mobile schools, and free — or subsidized — school meals. By 2015, primary-school enrolment had reached 91%.

Such an approach can also be used to grow secondary and tertiary education. Researchers can help nations to understand more about who is not attending school and why — and then put that information into the hands of decision makers and funders.

Education is a right — as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Education is also linked to better health and prosperity. It is essential to solving the many problems the world is facing, from climate change to the coronavirus pandemic. The generation of children now in schools is going to inherit a world that seems to grow more unstable with each passing decade. We need to equip them with every tool they will need — and that includes the best education.

Read the paper: Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets

Read the paper: Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets

Tracking inequalities in education around the globe

Tracking inequalities in education around the globe

How to make development funds go further

How to make development funds go further

Mapping disparities in education across low- and middle-income countries

Mapping disparities in education across low- and middle-income countries