The virus first surfaced at the end of 2019 in an animal and seafood market in Wuhan, central China.Credit: Noel Celis/AFP/Getty

As hundreds of millions of people in China take to the roads, railway and skies to be with their families for the new year holidays, authorities in the country and around the world have mounted an enormous operation to track and screen travellers from Wuhan in central China.

This follows the outbreak of a mysterious pneumonia-like coronavirus, first reported on the last day of December 2019, that has so far claimed six lives in China. The World Health Organization is deciding whether to declare the situation an international public-health emergency.

The virus has been spreading. On 21 January, as Nature went to press, there were almost 300 reported cases — seven times the figure stated five days earlier. Over the past week, authorities in South Korea, Thailand and Japan have also reported cases. Researchers at Imperial College London who have modelled the outbreak on the basis of estimates of travel out of Wuhan say the virus might have infected as many as 1,700 people.

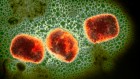

The virus, which still lacks a formal name, is being called 2019-nCOV. It is a relative of both the deadly severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) viruses. People with the virus report a fever along with other symptoms of lower-respiratory infection such as a cough or breathing difficulties. The first people infected in China are understood to have caught the virus in one of Wuhan’s live animal and seafood markets — probably from an animal. Some 95% of the total cases, including those in Japan, South Korea and Thailand, also involved people who had been to Wuhan.

The virus has not been found in humans before and knowledge of how it is spread is still evolving. Last week, government officials and researchers in China who are tracking the virus told Nature they didn’t think it spreads readily from human to human, at least not as fast as SARS. But this view is being revised following the intervention of SARS specialist Zhong Nanshan. After a visit to Wuhan on 20 January, Zhong, who directs the State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease in Guangzhou, confirmed that 14 medical workers had been infected by one virus carrier, raising concern that some people might be ‘super-spreaders’ of the virus. Stopping the further spread of the disease out of Wuhan, possibly by banning infected people from leaving Wuhan, has to be a top priority, he said.

China’s health authorities and the government have been moving quickly. Also on 20 January, the national broadcaster reported that president Xi Jinping had ordered that the virus be “resolutely contained”, and Premier Li Keqiang announced a steering group to tackle disease spread. At the beginning of the month, local authorities in Wuhan closed and disinfected the animal market, and health authorities have reported the results of their disease surveillance efforts.

Researchers, too, have had a crucial role, in publishing and sharing genome sequences. Four different research groups sequenced the genomes of six virus samples — and analyses of all six agree that the virus is a relative of SARS. Researchers are to be commended for making sequence data available, and they should continue to do so. (Release of such data, as well as deposition of manuscripts on preprint servers, will not affect the consideration of papers submitted to Nature.)

As China’s government has recognized, the authorities fumbled in their response to SARS, which spread globally, killing more than 770 people in 2002–03. Fifteen per cent of those infected died, a rate that seems much higher than that of the current outbreak — at least from what is known so far. In contrast to SARS, the response this time has been faster, more assured and more transparent.

But there is still much to do, and quickly. The virus’s original source must be confirmed — something that is proving difficult. Researchers have found virus traces in swabs taken from the animal market. The authorities, rightly, made closing and sterilizing the market their first priority, but in their rush to do so they might have missed a chance to test the animals. In the case of SARS, we now know that bats transmitted the virus to other animals, which then passed it to humans. Other questions include confirming the method of transmission for new cases, as well as understanding the virus’s ability to cause serious illness. Virus genomes from infected people will need to be sequenced continually to understand the extent to which the virus is evolving.

China’s health authorities did well to act more quickly than in the past. Now, they must continue to report what they know and what more they are uncovering. The emerging situation requires global coordination and leadership from the World Health Organization, with the support of public-health agencies worldwide. Researchers must work fast, collaboratively and transparently to address the key research questions. The world has had plenty of practice with SARS and avian flu — we should know what to do.

Around 7 million people are preparing to fly from China to 400 cities in 100 countries to celebrate the Chinese New Year. Now is the time to stop this outbreak spiralling into a global health emergency.

New virus surging in Asia rattles scientists

New virus surging in Asia rattles scientists

New virus identified as likely cause of mystery illness in China

New virus identified as likely cause of mystery illness in China