Researchers used China as a case study to test a new index for the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The country has made progress in the category of affordable and clean energy such as solar power.Credit: Kevin Frayer/Getty

How can a country tell that it’s making progress on sustainability? How can it work out, from year to year, whether its environment is improving, along with the economy and well-being?

This is incredibly difficult. A successful measure must have at least three characteristics: it needs to be based on a comprehensive set of reliable data; it must be accessible to non-specialists; and it has to be updated regularly and presented so that progress (or lack of it) can be seen easily.

For decades, researchers and policymakers have been searching for a measure that everyone can agree on. But most efforts, from the Human Development Index to the Genuine Progress Indicator, end up lacking some aspect of those three characteristics.

Get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track

The need is becoming more urgent now that the international community is set on its 2030 deadline to meet the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to end poverty and hunger, tackle climate change and more.

The UN publishes an annual report that ranks countries on their progress towards each goal, with a score out of 100. It shows how nations are doing relative to each other and whether they’re on track to meeting the goals (most are not). But the report doesn’t record local-level data, and inter-year comparisons are hard.

For example, Denmark — the top-ranked country in the 2019 report, with an impressive aggregate score of 85.2 — still has some way to go in reaching Goal 14, which measures the health of the marine environment (‘life below water’). But those who want to know whether Denmark’s score has improved over time are forced to comb through PDFs of the previous years’ reports, and these include nothing comparing different parts of the country.

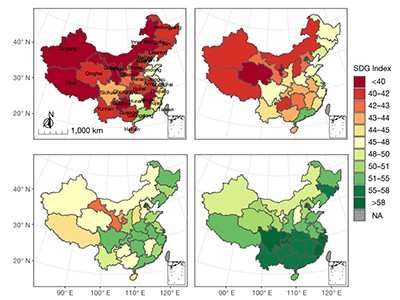

But help could be at hand. In Nature this week, a team led by researchers from Michigan State University in East Lansing and China Agricultural University in Beijing show how it’s possible to use the SDG reporting framework to construct an index that allows progress to be compared across regions and over periods of time (Z. Xu et al. Nature 577, 74–78; 2020).

Read the paper: Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time

The team chose China as its case study, and the results show that the country’s overall SDG score increased from 45.5 in 2000 to 55.4 in 2015. Each of its 31 provinces also increased its score. Nationally, the trend is in the right direction, although the rate of progress so far is not enough to meet the 2030 target. Moreover, China’s scores have fallen in four goals — life below water, responsible production and consumption, gender equality, and climate action.

Can such an approach to data gathering be scaled up? Yes, but it needs a large literature base to draw on, and public authorities must be willing to recognize the value of such an effort — and must know how to use it.

China’s government is aware of the environmental and social risks of rapid industrialization, and the country has an active community of researchers and policymakers working on sustainability measures. The authors of the paper went to national data sources such as the National Bureau of Statistics of China, as well as specialized sources that hold data on health, energy and population — all of which are accessible for research. But that is expensive on a global scale. In many low- and middle-income countries, especially, the infrastructure to collect such data still needs to be built.

This work is a milestone, nonetheless, because it shows how it’s possible to measure detailed progress towards the SDGs, and to reveal where countries fall short. With 17 goals and just 10 years in which to achieve them, the world needs better measures to see both how far we have come, and how far we have to go.

Read the paper: Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time

Read the paper: Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time

Get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track

Get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track

Sustainable development will falter without data

Sustainable development will falter without data