Scientific and technological innovation has always created social and economic transformation. But the past decade showed, as few others have, the speed and scale at which such change can happen. If it continues at the present rate, the shape of the next ten years — from information technologies to applied bioscience, energy and environment — looks ever more contingent on the discoveries made in that time.

In the 2010s, artificial intelligence (AI) finally began to reveal its remarkable power and disruptive potential. Driven mainly by the advent of deep learning — the use of neural networks to spot patterns in complex data – AI flexed its muscles by achieving reliable language translation, besting expert human players at poker1, video games2 and the board game Go3, and beginning to demonstrate its use in self-driving cars (see Nature 518, 20–23; 2015).

Few fields are untouched by the machine-learning revolution, from materials science to drug exploration; quantum physics to medicine. Moreover, it now cannot be doubted that many jobs currently performed by humans could be done more cheaply and efficiently by machines — and the transition might well come sooner than we expect.

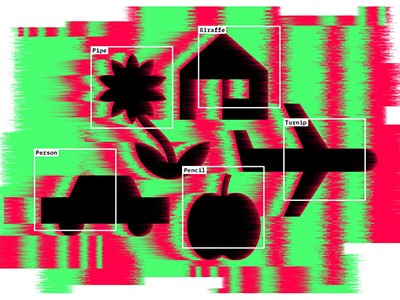

Why deep-learning AIs are so easy to fool

These impacts have intensified discussions of risk, but the current danger is not from a Terminator-style robot insurrection. Instead, it will come from inappropriate — or simply bad — uses of the computational tools at our disposal. Algorithms are still unable to automate many human qualities, such as the subtle cognitive capacities we otherwise call common sense. Tomorrow’s machines will need to make use of nuanced reasoning and more accurate representations of reality, which demands conceptual advances and architectural innovations as well as bigger circuits.

Appropriate uses of AI must also acknowledge that algorithms trained on the results of past human performance are likely to inherit our biases and prejudices, banishing the idea that an automated process is inherently an objective one4. Scientists attempting to develop more humane and dependable AI in the coming decade must heed the call for an interdisciplinary science of ‘machine behaviour’5 that draws on the skills of psychologists, sociologists, philosophers, legal scholars and researchers in other disciplines of the social sciences and humanities, along with specialists in engineering and physical sciences.

“There is an entity that cannot be defeated.” The words of South Korea’s Lee-Sedol who has quit playing the ancient Chinese board game Go, after successive defeats at the hands of Google’s AlphaGo.Credit: Lee Jin-Man/AP/Shutterstock

Regulating at speed

The influence of the information revolution has been felt most strongly in data-rich fields of research. In the life sciences, this has helped to transform the study of the microbiome, the genetic material of all the microorganisms found in particular environments (see go.nature.com/2yy70bo). In turn, this has affected everything from our appreciation of the importance of microbes in how organic matter decomposes, to our understanding of their role in human diseases. Similarly, the study of human evolution has expanded its focus beyond bones and stones to also include genes and proteins that are now helping to reveal the complexities of evolution, migration and population structure (see go.nature.com/38pdi6m).

It was clear by 2010 that the glut of information made available by the falling costs and growing speed of genome sequencing was going to be both valuable and challenging. But since then, there have been some stark wake-up calls.

Some researchers are deploying Big Data and computing power to explore genetic contributions to highly complex issues, such as behaviour or educational attainment (see Nature 574, 618–620; 2019). The reality is that any such links are diffuse and poorly understood. In spite of this, companies offering genetic tests are expanding into what they see as a potentially lucrative market for ‘predicting’ intelligence, and it is likely that products claiming to predict other traits will follow. This is happening ahead of any consensus among researchers about the reliability and value of such tests, let alone their proper regulation.

How human embryonic stem cells sparked a revolution

Another frontier that researchers have continued to push forward in the past decade is the reprogramming of mature human cells to a stem-cell state. The ability to induce pluripotency — the capacity to transform into multiple tissue types — makes it feasible to grow new cells of almost any variety from adult cells. These are now finding use in exploratory clinical procedures for treating degeneration or damage of retinal and neural tissue — but here, too, there is a burgeoning market for unproven and potentially unsafe ‘treatments’.

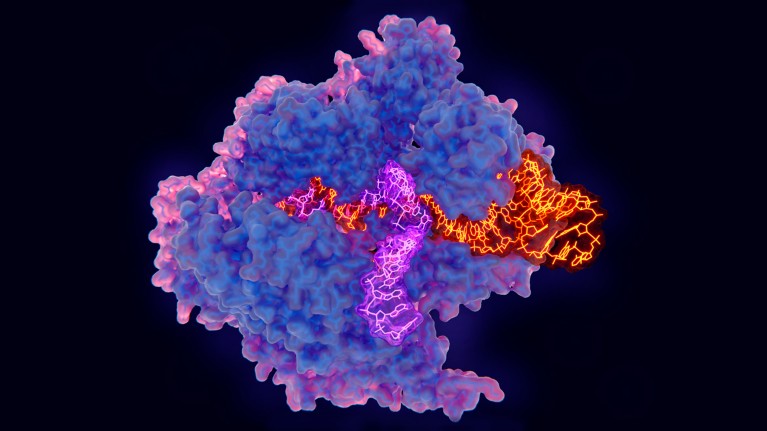

The 2010s also saw the CRISPR–Cas9 technique6,7 harnessed in the cause of genome editing. But for years, the consensus was that no scientist would go so far as to edit a gene in the germ line — human sperm, eggs or embryos — given both the possible dangers to any resulting child, and the unresolved ethical issues involved in making heritable changes. That situation changed, however, when the scientist He Jiankui announced in November 2018 that he had used CRISPR to edit a gene in two baby girls born as a result of in vitro fertilization, drawing worldwide condemnation (see Nature 563, 607–608; 2018).

Human genome editing: ask whether, not how

As the World Health Organization and academies of science and medicine race to draw up guidelines for regulation, we need to reflect on why ethical and regulatory frameworks have lagged behind scientific and technological advances (see Nature 575, 415–416; 2019). At the same time, researchers must consider what can be done now to ensure that technologies are not implemented unless they are shown to be sufficiently safe, effective and inclusive (see Nature 576, 7–8; 2019). Here, too, is the troubling possibility that a market demand based on false promises will ride roughshod over the sober deliberations of the scientific community.

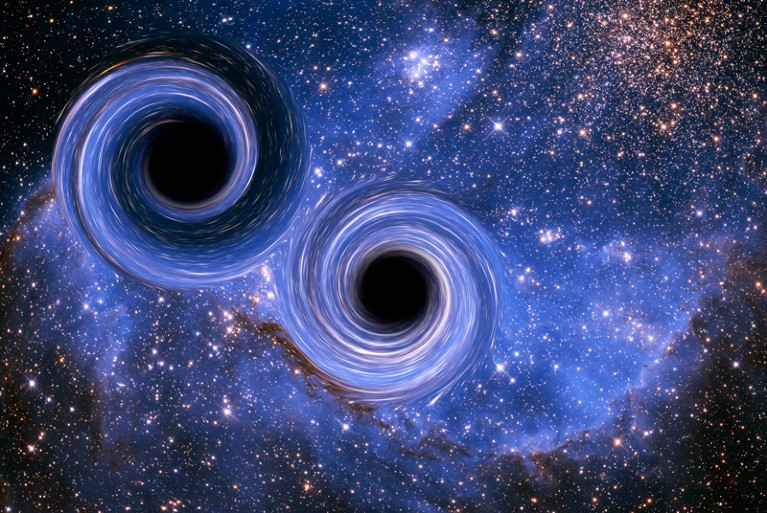

Space-time rocks

The 2010s also showed why, in anticipating the coming decade, we should never underestimate scientists’ ingenuity and their ability to overcome the odds — given enough resources, and support from funding agencies, industry and decision makers.

In 2008, researchers at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, switched on the Large Hadron Collider, one of the world’s most expensive scientific collaborations. In 2012, they confirmed8,9 that they had found the Higgs boson, as predicted by particle physics’ standard model.

The collision of two black holes helped confirm the existence of gravitational waves, a century after they were predicted in Einstein’s general theory of relativity.Credit: Victor de Schwanberg/SPL

Four years later, in 2016, the announcement that researchers had detected gravitational waves10 represented the success of a technique that many originally deemed too difficult. The general theory of relativity had long predicted that violent astrophysical events might cause tiny oscillations in space-time; this idea was eventually confirmed by laser interferometry of breathtaking precision. Two experiments — the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in the United States and Virgo in Italy — have now been able to measure changes in the dimensions of space-time of a fraction of the diameter of a proton, caused by waves created in the collisions of black holes or neutron stars. With more detectors coming online and powerful upgrades implemented on existing instruments, gravitational waves are now taking their place as windows on the universe, alongside electromagnetic frequencies from radio waves to γ-rays.

Beyond quantum supremacy: the hunt for useful quantum computers

Similarly, as the decade began, quantum computing looked like a good idea on paper but a distant prospect in practical terms. Not so today: even the field’s specialists have been surprised at how quickly the first devices have evolved. IBM made its five-quantum-bit computer available on the cloud in 2016; the decade ends with machines from IBM, Google and others boasting quantum-bit arrays an order of magnitude larger. One big challenge in the next decade will be to find more ways to make use of these resources, by developing a wider range of quantum algorithms.

China’s development of quantum information technologies is just one indication of the nation’s remarkable rise as a research superpower. Chinese scientists have used quantum methods to secure long-distance data transmission, for example by pioneering the use of quantum teleportation11 to send information across the world securely by satellite, and by installing an inter-city fibre-optic network that constitutes the first stages of a quantum internet. China’s government is also looking to shape the global landscape of research in its Belt and Road Initiative: a programme to build infrastructure, including roads, railway lines, ports and even whole cities, all over the world (see Nature 569, 5; 2019).

Football on the Greenland ice, but for how much longer?Credit: Marius Vagenes Villanger/Kystvakten/Sjoforsvaret/NTB Scanpix/Reuters

The coming climate crunch

Environmental crises have become depressingly familiar in the past decade, and the alarming rate of global warming lies behind many of them. The latter half of the decade — 2015 to 2019 — was the warmest five years on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization. The pace of warming means that the window for avoiding temperature rises of 1.5 or 2 °C above pre-industrial levels is now frighteningly small. The 2020s will be make-or-break. If carbon emissions are not drastically reduced by 2030, we will be entering uncharted territory, including the possibility — albeit subject to much debate — of passing irreversible tipping points12, such as the widespread loss of Antarctic ice.

The hard truths of climate change — by the numbers

Many countries are now investing for the long run in new energy technologies. The next milestone in the promise of fusion-powered energy will be the switching-on of the international ITER reactor in the south of France in 2025. But any benefits of fusion are too far off considering the urgency of climate change. ITER’s road map places the moment of sustainable net power gain around 2035, with commercialization unlikely until at least mid-century.

That means that other ways to create energy while reducing carbon emissions need to become viable on a large scale in the coming ten years. Researchers must pursue innovative technologies such as carbon capture or splitting water through artificial photosynthesis, but solutions must also include significant changes to how the energy economy is run. Navigating a more sustainable path will require ambitious political and industrial will, as much as scientific ingenuity.

In many countries — especially those afflicted by varying degrees of authoritarianism and climate-change denial — that will is in short supply. But researchers must not lose hope. Working with civil society, they must step up, get out of their comfort zones and recognize activism as part of their mission13. And they must fight to restore the status of facts and truth.

The 2010s were both remarkable but also troubling. With new knowledge, and a renewed dedication to social and environmental responsibility, the 2020s must be transformational.

Watch: The science that shaped a decade:

The best science images of the year: 2019 in pictures

The best science images of the year: 2019 in pictures

Robots, hominins and superconductors: 10 remarkable papers from 2019

Robots, hominins and superconductors: 10 remarkable papers from 2019

Books for our time: seven classics that speak to us now

Books for our time: seven classics that speak to us now

Trickster microbes, manels, Venus: Nature’s best long reads of 2019

Trickster microbes, manels, Venus: Nature’s best long reads of 2019

Nature’s top ten books of 2019

Nature’s top ten books of 2019

Dispatches from a world in turmoil

Dispatches from a world in turmoil