Astronomer Wanda Diaz-Merced uses apps that improve conference accessibility.Credit: Marla Aufmuth/TED

Conferences can be tough for people with disabilities and chronic illnesses. Four scientists talk about their own conference challenges and positive experiences, and give advice for other researchers and event organizers.

MONKOL LEK: Plan ahead

Assistant professor at the Department of Genetics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

I have a rare form of muscular dystrophy, and can’t walk long distances. I use a wheelchair, or I just struggle. I trip easily and can’t get off the ground when I do.

When people are invited to give conference talks, everyone gets so excited. My first thought is ‘how am I going to get on the stage?’ I also wonder if the conference venue is accessible, how far it is from the hotel and how I can sit in such a way as to not to cause a ruckus. I’m thinking about all the things that people without a disability just don’t think about. It takes the fun out of being selected to give a talk.

I can tell you about one epic fail. I was speaking at the 2019 annual meeting on rare diseases in Beijing, hosted by the Beijing Society of Rare Diseases. I was the only international speaker in that session; there were about 1,000 people in the audience. I was walking with a walking stick from a seat close to the stage, which was elevated by only 60–80 centimetres, so it was possible for me to transfer from a standing position to a chair on the stage that I had asked for. The transfer went fine, but when I got up from the chair to speak, there were too many people crowding me to help. I tripped over their feet and had to use the chair to get up off the stage floor. It was really embarrassing and, looking back, I kind of did a shit job on the talk. My hosts are always lovely, but they can forget about accessibility because it’s something they don’t deal with every day.

I go to three to four conferences, university visits and other meetings a year. I probably turn down three to four more because my body can’t take all the travelling. I travel with my wife; she is a scientist and we have to balance her career goals, too. My colleagues are constantly at conferences, and I feel like I’m missing out on opportunities to network and build new collaborations.

My advice to people with physical disabilities is: don’t be embarrassed to contact event organizers in advance. Before I went to the Biology of Genomes conference at Cold Spring Harbor in New York, I learnt there was a long walk between the conference centre and where we were staying. The organizers confirmed there was disabled parking available. That made my life so much easier.

WANDA DIAZ-MERCED: Networking challenge

Independent professional astronomer.

Being blind, the major challenge I face at meetings is networking. Trying to locate people, knowing who is in the room, trying to approach and talk to them is challenging. I am unable to have spontaneous conversations.

I go to four or five astronomy meetings a year, and there is a lot of preparation to do. I call the hotel and conference venue and ask about accessibility, whether the hotel is easy for taxis to reach, and if they have markings on the floor so I can find my room and the breakfast place. I like to do things by myself.

There are many things I miss out on. If conference rooms are too distant from each other and there are landmarks that I am not aware of because I didn’t attend an orientation, I might lose the opportunity to go to sessions. It’s hard to ask anyone walking around to take me to a room: I don’t know who is there or how distant they are. Bringing a companion can solve the situation, but not all astronomical observatories have the money, and I worry that asking them to pay for someone to accompany me might mean I lose opportunities in the future.

I presented at a TED conference called Dream in Vancouver, Canada, in 2016. It was a completely different experience. It had an app that let you know who would be at the conference and what they would be talking about, so I could get in touch and plan to meet with people in advance. There was a sensor in your conference badge that was always scanning and updating the app with the location of people, so you knew who was in the room. The organizers also gave information about dietary requirements on the menu. I’m diabetic and I didn’t have to point that out to anyone. Those accommodations made a huge difference, I felt free to be myself. I still keep in touch with 10 or 12 people that I met at that conference.

My advice to organizers is to ensure your conference allows everyone to interact.

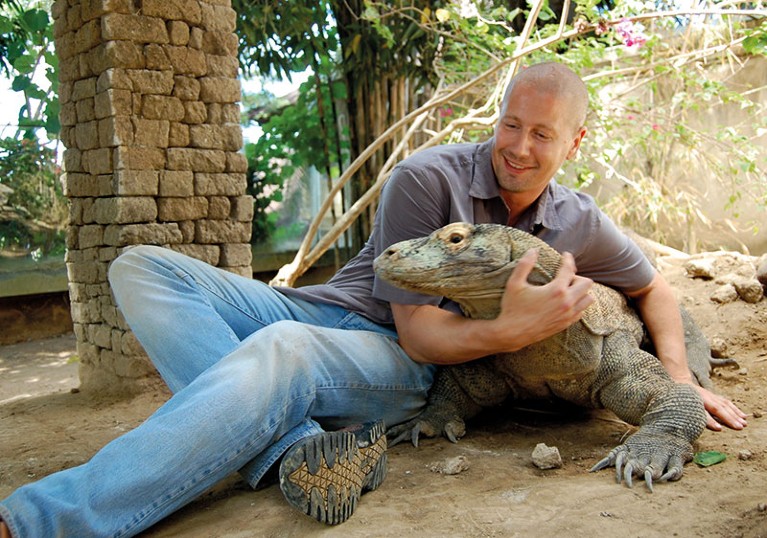

Biochemist Bryan Fry, who has hearing loss, studies the venom of Komodo dragons.Credit: Kristina Formuzal

BRYAN FRY: Audio technology

Venom researcher and biochemist at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Audio at conferences is not always the best, and can be a challenge as a person with hearing loss.

I remember an awkward situation at one question-and-answer session when I was presenting, and one person who asked a question wasn’t speaking very clearly. They had a thick accent, but that wasn’t the problem. It was that they weren’t using the microphone properly. I kept asking them to repeat the question, and they ended up thinking that I was making fun of their accent. I could see them getting visibly upset. A couple of people giggled in the audience. It led to a colossal misunderstanding. I explained to them afterwards that I had hearing loss, but I don’t think they believed me.

Because of nerve damage in my ear, there’s no hearing device that works for me. If someone’s talking on my right side, they might as well not exist. At round-table meetings or conference dinners, if there are more than four people or if we’re at a loud restaurant, I have no hope of staying involved in the conversation. After a while, it becomes incredibly isolating. I also have bad balance that’s related to hearing loss. When I’m walking through a crowd, I might bump into people, or I’ll walk into a wall and someone might think that I’m drunk. I have to accept that there’s going to be some misunderstanding or lack of participation and interaction. Not all disabilities are visible.

The best conference I have been to was ‘Snakebite — from science to society’, last year in the Netherlands, which I helped to arrange. I brought up hearing and the other organizers had already made plans for accessibility. They had a number of small loudspeakers dotted around the conference hall, so that you could be sitting at the very back and have the same level of volume directed at you as someone sitting at the front. They were also clear about microphone use. They actually stopped a couple of people and gave guidance about holding the microphone.

I design my slides with key bullet points accompanying images, so that you could be wearing noise-cancelling headphones and still get the essential information. Often slides are extremely pictorial, but if you can’t hear what the speaker is saying, you can’t understand. I don’t think it’s lack of caring. I think there’s just a lack of awareness about these sorts of issues.

GABI SERRATO MARKS: Empathy for yourself

PhD candidate in marine geology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Because I have Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, which is a connective-tissue disorder, I struggle standing for more than 10 minutes, which makes dinners or receptions and other networking sessions difficult. Often there are no non-alcoholic drinks apart from water, which is frustrating. Many people with disabilities and chronic illnesses don’t drink because it can exacerbate our symptoms. But it’s nice to have a drink in your hand to match everyone else.

I visited one conference a while ago and there were only standing tables and finger foods, most of which I couldn’t eat because I have dietary restrictions. Some of the food wasn’t labelled. It felt like it wasn’t designed for people with disabilities.

This year, the Geological Society of America conference in Phoenix, Arizona, was better. It had a section in the registration form that solicited suggestions to make the conference better ahead of the event. Someone reached out before the conference and asked what I needed. Having a person there to help made me feel like I belonged. That support meant that I could actually present a poster and be there; otherwise I would have declined the invitation.

When I was first diagnosed, I felt so alone and as if I couldn’t be a geoscientist if I had a disability. That’s part of why I try to be really vocal about it — writing opinion pieces, using social media, speaking at conferences and speaking up in person when I need accommodations. I get messages from people who say, “Oh, I’ve dealt with health issues for my whole career and I keep it pretty quiet, but I really appreciate that you’re talking about this.”

I encourage anyone who has a disability or a health issue to try to imagine if a friend came to you and said, “I feel really exhausted and I don’t think I can make it to this event. Do you think that’s OK?” You would probably tell them, “Of course it’s OK. You should go home.” Have the same empathy for yourself. You should do whatever you need to do to be able to access the conference. That’s the important thing.

How the scientific meeting has changed since Nature’s founding 150 years ago

How the scientific meeting has changed since Nature’s founding 150 years ago

From social media to conference social

From social media to conference social

How to organize a conference that’s open to everyone

How to organize a conference that’s open to everyone

Disability awareness: The fight for accessibility

Disability awareness: The fight for accessibility

The secrets of a standout seminar

The secrets of a standout seminar