In the film Terminator: Dark Fate, Linda Hamilton plays Sarah Connor as an older woman — a demographic that’s rarer in science-fiction novels.Credit: Kerry Brown/Paramount/Everett Collection

As women get old, they gain a superpower: invisibility. And not only in real life. ‘Young adult’ fantasy and science-fiction hits such as Suzanne Collins’s novel series The Hunger Games and Stephenie Meyers’s Twilight series have been taken to task for doing away with mature women. In fantasy generally, older women mainly occupy supporting roles, such as fairy godmothers, wise crones and evil witches. The best are subversions — George R. R. Martin’s Queen of Thorns in A Song of Ice and Fire, for instance, or Terry Pratchett’s wonderful Granny Weatherwax and Nanny Ogg in the Discworld series. All of them embrace old age with gusto.

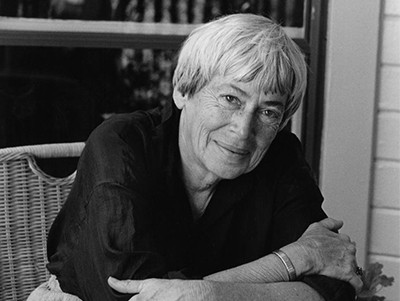

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

I expected better from science-fiction novels, where alternative worlds and alien nations explore what it means to be human. In 1976, after all, Ursula K. Le Guin argued in her essay ‘The Space Crone’ that post-menopausal women are best suited to representing the human race to alien species, because they are the most likely to have experienced all the changes of the human condition. And Robert A. Heinlein offers a fantastic galactic grandmother in The Rolling Stones (1952): Hazel Stone, engineer, lunar colonist and expert blackjack player irritated by the everyday misogyny of the Solar System.

Over the past year, with support from such authors and readers all over the world, I’ve searched for competent, witty female elders in major roles in sci-fi novels. I found no shortage of fantastic female characters across the genre, from the gynocentric utopians of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 Herland to mathematician Elma York in Mary Robinette Kowal’s 2018 The Calculating Stars. But I have so far confirmed just 36 English-language novels in the genre that feature old women as major figures. The earliest is Gertrude Atherton’s 1923 Black Oxen; the latest, from 2018, are Blackfish City by Sam J. Miller and Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers.

A long way from home by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

Experience gap

It’s a notable gap. Old men with deep expertise and experience throng sci-fi, from ancient keeper to eccentric mentor, retired badass and wasteland elder. And non-binary gender possibilities are explored in books such as Octavia Butler’s 1987 Dawn and Kameron Hurley’s The Mirror Empire (2014).

Over the past century, women in the real world have been increasingly likely to become researchers, doctors and engineers. Indeed, most fields in science, technology, engineering and mathematics now recruit a growing proportion of women. But women are still under-represented among senior scientists, owing to the ‘leaky pipeline’ — they leave the field disproportionately in response to systemic bias.

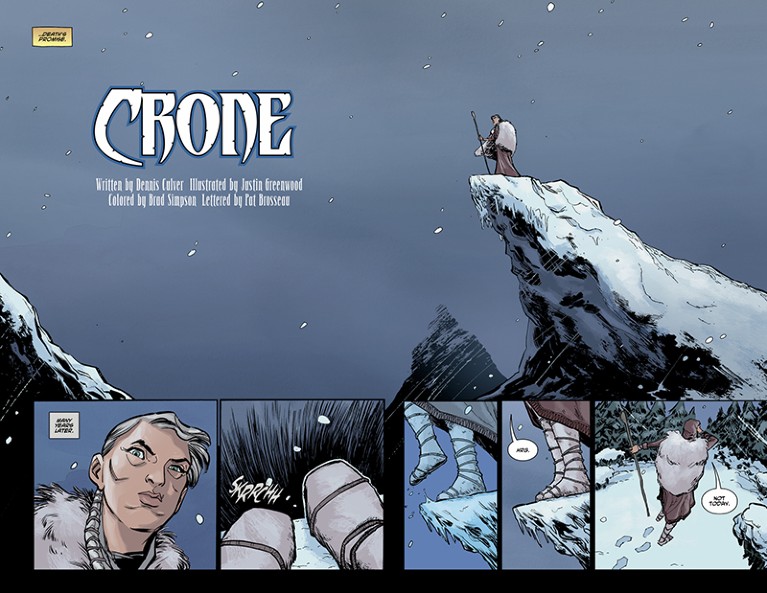

The comic Crone follows the adventures of a returning heroine grown old.Credit: Dennis Culver, Justin Greenwood, Brad Simpson, Pat Brosseau/Dark Horse Comics

And science fiction has magnified that issue. Rather than countering bias against ageing women, sci-fi writers seem more interested in making them young again — even expediting the rejuvenation process by casting it as a modern convenience akin to jet packs and replicators. Yet again, only a few of the novels I found featuring technological fountains of youth include old women. Paula Myo in Peter Hamilton’s Commonwealth Saga (2004) and Sarah Halifax in Robert Sawyer’s Rollback (2007), for example, consider the side effects of gaining life experience without apparent ageing. John Scalzi’s Old Man’s War (2005) is a thought-provoking parody of the ‘body-snatching’ trope, in which a new body is taken to replace a worn one, showing the psychological perils of renewal that’s only skin-deep.

Science fiction when the future is now

Age-reversal technology should apply to all genders: why would anyone get physically old if they didn’t have to? And yet, amid the fictional horde of seasoned male mentors and stewards, sci-fi authors struggle to imagine a similar function for aged women.

All this reflects a general societal reluctance to see ageing as a natural process. The global anti-ageing market is currently worth more than US$50 billion, mainly targeting women aged 35 to 55 in a kind of heckling by advertisement. Many women are reluctant to describe themselves as elderly from fear of stereotypes that define older women as isolated and fragile. If a woman is smart and social and competent, the stereotypes say, she must not be old.

Double dearth

I found a clear lack of cultural diversity in the female elders of sci-fi, almost as if there’s a quota. Even when I focused on Afrofuturism, searching the works of Butler and fellow pioneer Samuel R. Delany, I found older women of colour only in short stories and fantasy novels. Many point to Le Guin’s anarchist leader Laia Asieo Odo. However, Odo is middle-aged when described in The Dispossessed (1974), and old (and nearing death) only in the short story ‘The Day Before the Revolution’. Similarly, Essun of N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy is in her forties. I discovered just one major character who met all the criteria: Mother Abagail from Stephen King’s The Stand (1978).

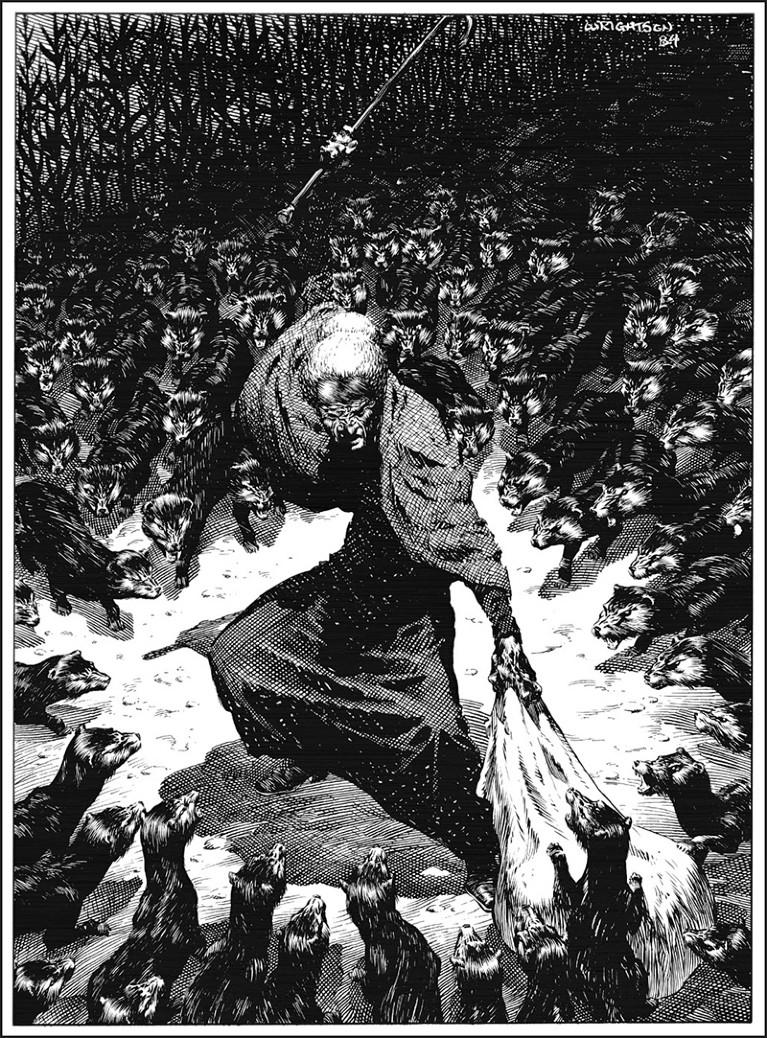

In Stephen King’s The Stand, Abagail Freemantle becomes a spiritual leader as a centenarian.Credit: Checkman111/CC BY-SA

UK sci-fi authors, I found, consistently portray only white old women as British. Women of colour are always described as coming from other countries or realms; I have noted no representation of actual UK diversity. US writers have a similar record, with one exception. Three female elders from Native nations feature prominently in novels: Masaaraq from Blackfish City; Jenny Casey from Elizabeth Bear’s Hammered (2004); and Kris Longknife in the eponymous series by Mike Shepherd.

Project daffodil by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

Celibacy is another distinguishing feature of the few female elders there are in sci-fi — despite studies showing that around half of women over 40 (including a significant number of over-80s) are sexually active and satisfied (S. E. Trompeter et al. Am. J. Med. 125, 37–43.e1; 2012). Madame Zattiany of Black Oxen, for instance, remains uninterested in sex despite a glandular ‘rejuvenation’ that leads to an affair with a much younger man. (Despite the lack of libido, it is her inability to bear children that dooms the relationship.) Interestingly, the elderly female characters who show any interest in sex are clearly defined as lesbian or bisexual, such as the killer-whale-riding warrior grandmother in Blackfish City. As for menopause, it is glossed over in the qualifying books, in sharp contrast to the prevalence of puberty-related tales. That is a definite reflection of the dearth of research around menopause, and of support for women undergoing it.

I have shared my data through an open mailing list, and asked for input at presentations at major sci-fi conferences in Europe. Recently, I received an e-mail asking why I expected ‘crones’ to appear in sci-fi at all. Shouldn’t youth take centre stage, the author asked, with the added advantage of romantic potential? This summarizes the attitude that, after a certain age, women are uninteresting or threatening — and need to be got out of the way. More than 20% of US citizens will be 65 or over by 2035. The real-world grey tsunami cannot be halted. It could be considered a blessing, if we were to collectively focus on the strengths of older people, and foster healthspan as well as lifespan.

The wise old crone might not be a useful trope. However, science fiction could and should explore new roles for female elders as multifaceted beings. Authors have an opportunity here. With so few venerable women in major roles, a single novel including a new manifestation (say, a crime-solving octogenarian tribble rancher or a trans woman over 50) could completely change the landscape. Grandma is marvellous already; she doesn’t need to look like a teenager.

A long way from home by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

A long way from home by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

Project daffodil by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

Project daffodil by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

Women in science: Weird sisters?

Women in science: Weird sisters?

Science fiction when the future is now

Science fiction when the future is now