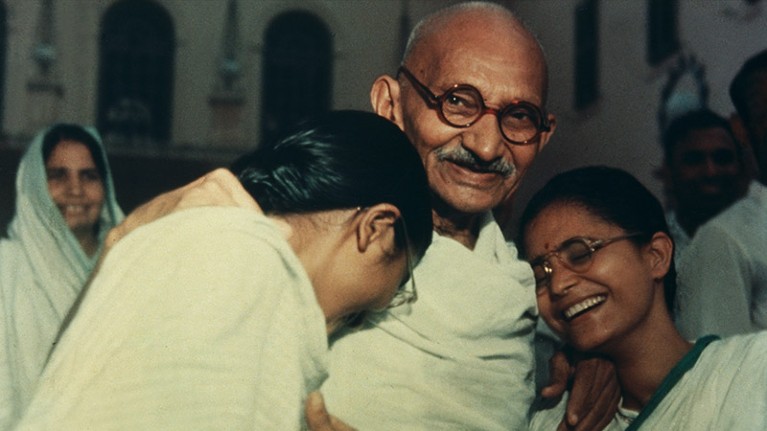

Gandhi crowdsourced ideas on how to improve the lightweight spinning wheel.Credit: Rühe/ullstein bild/Getty

India’s tourist shops do a good trade in Gandhi memorabilia. One particularly popular souvenir is a plaque that lists Mohandas Karamchand (Mahatma) Gandhi’s ‘seven social sins’. These include ‘politics without principles’, ‘commerce without morality’ and ‘science without humanity’.

During his lifetime and after his assassination in January 1948, Gandhi, the human-rights barrister turned freedom campaigner, has been mischaracterized as anti-science — often because of his concerns over the human and environmental impacts of industrial technologies.

But in the month that the world commemorates the 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth, it is time to revisit our understanding of this aspect of his life and work. Gandhi was a keen student of the art of experimentation — his autobiography is subtitled ‘The Story of My Experiments with Truth’. He was an enthusiastic inventor and an assiduous innovator, making, discarding and refining snake-catching tools, sandals made from used tyres, and methods for rural sanitation, not to mention the small cotton-spinning wheels that would become his trademark.

Anil Gupta at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, who has researched rural innovation in India for 40 years, says that Gandhi was also an early adopter of developing and improving technologies using crowd-sourcing — in 1929 he announced a competition, with a cash prize, to design a lightweight spinning wheel that could produce thread from raw cotton. It would be of solid build quality that would last for 20 years. “Gandhi was an engineer at heart,” adds Anil Rajvanshi, director of the Nimbkar Agricultural Research Institute in Phaltan, India.

Gandhi adopted experimental methods equally in his planning and execution of civil-disobedience campaigns against colonial rule. That legacy alone has endured to the extent that climate-change protest groups such as Extinction Rebellion describe themselves as following in a Gandhian tradition.

Gandhi drew the line at the resource-intensive, industrial-scale engineering that Britain brought to India after the first waves of the Industrial Revolution. Inspired in part by the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Ruskin, Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy, he called for manufacturing on a more human scale, in which decisions about technologies rested with workers and communities.

Gandhi was aware that he was perceived as being anti-science. His biographer Ramachandra Guha quotes a 1925 speech to college students in Trivandrum (now Thiruvananthapuram) in southern India, in which Gandhi said that this misconception was a “common superstition”. In the same address, he said that “we cannot live without science”, but urged a form of accountability: “In my humble opinion there are limitations even to scientific search, and the limitations that I place upon scientific search are the limitations that humanity imposes upon us.”

Gandhi understood that technology’s negative impacts are often felt disproportionately by low-income rural populations. In that same speech to the Trivandrum students, he challenged his young audience to think of these communities in their work. “Unfortunately, we, who learn in colleges, forget that India lives in her villages and not in her towns. How will you infect the people of the villages with your scientific knowledge?” he asked them.

In the end, Gandhi’s call for less-harmful technologies was out of sync with India’s newly independent leadership, and also went against the grain of post-Second World War science and technology policy-making in most countries. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was strongly influenced by European industrial technology and also by the model of large publicly funded laboratories — the forerunners to today’s vibrant and globally renowned institutes of science and technology. By contrast, Gandhi’s ideas were seen as quaint and impractical.

Influential figures from history often leave contested legacies. But in one respect at least, the space for debate about Gandhi’s life and impact has narrowed. As the world continues to grapple with how to respond to climate change, biodiversity loss, persistent poverty, and poor health and nutrition, Gandhi’s commitment to what we now call sustainability is perhaps more relevant today than in his own time.

The global south is rich in sustainability lessons that students deserve to hear

The global south is rich in sustainability lessons that students deserve to hear

A tour of India’s waste mountain

A tour of India’s waste mountain

Educating India

Educating India