Meeting organizers should better accommodate for attendees with disabilities, argue many scientists.Credit: Derek Meijer/Alamy

Having enjoyed their meal in a neo-Gothic, wood-panelled grand hall, most delegates were on their way to the afternoon sessions. Meanwhile, Caroline Miles had just spent 20 minutes sitting in her wheelchair looking at the back of the delivery van blocking her path to both the talk and the lunch.

Miles, a solicitor turned independent-researcher specializing in legal issues relating to social care, describes her attendance at the Socio-Legal Studies Association (SLSA) annual meeting at the University of Bristol, UK, last March as “demeaning and embarrassing and just horrible”. The talks took place across two buildings, and the lifts were frequently filled with participants who could have used nearby stairs. Her access was blocked by delivery vehicles on two occasions. When this made her late, sessions had to be interrupted as tables and chairs were rearranged to fit her in. Miles was provided with a dedicated support worker by the university, but says that networking took place in standing spaces that had no chairs at her level, and that access to disabled toilets was blocked by participants having refreshments.

As Miles waited for someone to find the driver of the delivery vehicle blocking her way into the main meeting venue for the second time, she finally gave up. “I burst into tears and said, ‘That’s it, I’m going home’.”

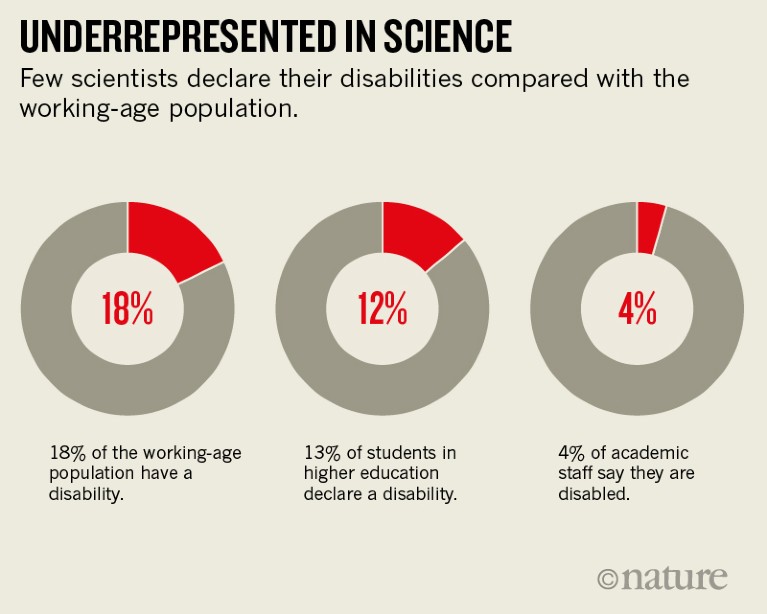

Miles’s experience is far from unique. Most universities claim to promote diversity and inclusivity, yet many researchers with disabilities and neurodiversities say they are routinely discriminated against. Statistics show that these groups are under-represented in academia. In the United Kingdom, for example, the government estimates that some 18% of the working-age population have a disability and that 13% of students in higher education declare a disability, yet only 4% of academic staff say they have one (see ‘Under-represented in science’).

Source: UK government

“The job market is competitive enough as it is,” says an archaeologist who has not disclosed her autism to the UK university that employs her, and asked to remain anonymous. “The fear is that if you disclose, employers will assume you can’t do the job or will need too many resources.”

Nicole Brown, who studies research and teaching methods at the University College London Institute of Education, agrees. She adds that those with disabilities and neurodiversities can also be put off or driven out of academia, because they are rarely given the time or funding they need to manage their condition and get their needs met. There is also a lack of understanding that although many academics might work mainly in linear, text-based ways, some might prefer more visual, embodied or spatial approaches, for example. “Many disabled people drop out because it is such a hostile environment for them,” Brown says.

Brown adds that meetings are set up in ways that prevent some people from participating fully, and that this illustrates the ableism that pervades academia. Yet, as she found when she helped organize the Ableism in Academia conference last March, hosting accessible and inclusive meetings is not difficult. Her starting point was simply to think about the needs of all potential attendees. Brown and her colleagues chose their venues carefully, making sure there was enough room to manoeuvre wheelchairs and mobility aids, and with easy access to toilets that could be unlocked with special devices known as RADAR keys, which are available only to people with disabilities.

It is not enough to just ask participants about their needs, because some might not want to disclose their conditions. “Even if nobody asks for accommodations, meeting organizers should still assume that of 20 people in the room, four or five will have disabilities, and cater for them accordingly,” says Jay Dolmage, at the University of Waterloo, in Ontario, Canada, and author of the book Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education.

Dolmage says that making presentations available in several ways, including as text scripts and large-print copies, and publishing them online, helps not only those with disabilities but anyone who wants to check references or refresh their memories later. Audio description of the visual elements in slide presentations widens access, as does the use of high colour contrasts, large font sizes and simple, sans-serif fonts.

The Ableism in Academia conference was live-streamed, allowing those who could not attend, and those who did not want to be in the busy main room, to follow talks. Live captions and sign-language interpreters were available. To widen participation, delegates were encouraged to use Twitter instead of more conventional approaches for questions and contributions.

Brown and her colleagues also provided a darkened quiet room equipped with blankets, cushions, eye masks and ear plugs for people to visit if the conference grew too intense. And Dolmage advocates the use of colour-coded interaction badges, which some event organizers, especially in the United States, provide so that wearers can let others know how they'd like to be approached socially at a particular time.

Meals, coffee breaks and drinks receptions provide spaces to share ideas, form collaborations and meet future employers. That’s why, Brown says, it is important to design these with inclusivity in mind. She hired a catering company that would provide lunch and snack choices suitable for those with diabetes, coeliac disease and allergies, for example. Preordered food was brought to participants at tables to avoid queues. “Imagine holding your plate in one hand and a glass in the other,” says Brown. “Now imagine doing that in a wheelchair or with a cane. It takes away those people’s opportunity to network.”

There are many other ways to promote inclusivity and diversity at meetings. Researchers say discrimination of the type experienced by Miles is mostly the result of a lack of consideration. “It’s not malicious or intentional,” says Brown. “It’s about people not thinking about different ways of being.”

Miles says her experience at the SLSA conference made her question whether academia was for her. However, she hopes that her complaints to its organizers and the venue’s managers might at least help them to improve the experiences of others with disabilities in the future.

The University of Bristol said that trained personnel, accessible toilets, lifts and parking were provided at the conference, adding: “We’re sorry to hear Caroline felt the provisions made did not fully meet her needs. Following her feedback, we now ensure delivery vehicles do not obstruct access points, have improved the signposting of stairs and ensure networking spaces do not obstruct accessible toilets.” An equality, diversity and inclusivity committee has also been set up in the university’s law school, which hosted the event.

How one conference embraced diversity

How one conference embraced diversity

How conferences are getting better at accommodating child-caring scientists

How conferences are getting better at accommodating child-caring scientists

Disability awareness: The fight for accessibility

Disability awareness: The fight for accessibility