Over the past few years, e-cigarettes containing increased concentrations of nicotine have attracted users.Credit: Volodymyr Melnyk/Alamy

For more than half a century, the world has known that tobacco kills — yet it is still killing more than 8 million people a year. Tobacco use remains the world’s worst entirely preventable public-health emergency, and there is a desperate need for fresh ways to tackle it.

So it is little wonder that e-cigarettes have attracted attention as a potential solution. More than half of US adult smokers try to quit each year: in theory, e-cigarettes might boost their chances of success. It is generally agreed that vaping is safer than smoking conventional cigarettes.

But even as e-cigarette sales have boomed — the global market was worth US$11.3 billion in 2018 — concerns have mushroomed, and research has failed to keep up. Urgent questions about vaping remain: whether it really does help people to quit smoking, whether it serves as a gateway to cigarettes, and whether the liquid formulations have short- and long-term health effects. Until such questions are answered, it seems premature to advocate strongly for e-cigarette use, and imperative that regulators develop guidelines to limit vaping by adolescents.

A UK study published this year highlights the evidence gap. In a large randomized, controlled trial, researchers found that smokers who used e-cigarettes to help them quit were less likely to start smoking again for at least a year, compared with those who used other aids such as nicotine gum or patches1. The study was one of the most rigorous so far — yet the benefit was slight, and 75% of study participants had already tried and failed to quit using the other cessation aids, so it was less surprising that they failed again. Overall, studies have not found strong evidence for a benefit of e-cigarettes over other quitting strategies — including nicotine-replacement therapy combined with antidepressants.

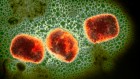

It’s also hard to say whether recent results will translate to the real world, where e-cigarettes are changing fast. Over the past few years, US vapers have flocked to devices that contain nearly three times the European Union’s legal limit on nicotine concentration. The most concentrated pods of the popular devices, made by Juul of San Francisco, California, for example, contain as much nicotine as a pack of 20 cigarettes.

There is huge concern about the surge of vaping among young people, and the potentially addictive nature of such products, which have been backed by aggressive marketing campaigns. Vaping among high-school students in the United States (14–18 years old) rose 78% from 2017 to 2018. One out of every 5 high-school students — and nearly one out of every 20 middle-school students, typically 11–13 years old — has vaped at least once in the past month.

This could be a major health concern. Many studies have shown that adolescents who vape are more likely to take up smoking, but none has established a causal link. And the long-term effects of e-cigarettes — particularly ones with a high nicotine concentration — on young brains remain unknown.

With so few data, researchers’ debate over e-cigarettes has been divisive and sometimes emotional. Proponents of e-cigarettes see a way to help the millions who are trying to quit smoking and stem the grave harm caused by tobacco. Vaping critics — some of whom have received death threats after giving public talks critical of the devices — fear they could lose ground in the decades-long battle against tobacco and create a generation of e-cigarette addicts. They see the spectre of Big Tobacco — the five largest global tobacco companies — rising again. That fear was further fanned when tobacco giant and Marlboro-maker Altria of Richmond, Virginia, purchased 35% of Juul last year.

Studies showing that cigarettes cause lung cancer turned tobacco into an enemy of public health. Now researchers, research funders, public-health agencies and policymakers must unite to provide answers about e-cigarettes by designing better studies, repeating those that have been done already and simultaneously addressing the next generation of nicotine products.

There are reports that manufacturers are looking at ways to increase the voltage of their devices, and so deliver more nicotine without raising the nicotine concentration of their juice — a way of sidestepping EU limits on nicotine content. And other devices are coming online: in Japan, cigarette smokers are increasingly using electronic products that heat tobacco without burning it, and the US Food and Drug Administration approved its first such product in April.

The right policies on e-cigarettes — ones that minimize risks — will be built on evidence and collaboration, not on opinion and vitriol. It might be too early to say whether e-cigarettes will make a major difference in helping adult smokers to quit. It’s the right time for regulators to protect the next generations from having to.

The United States must act quickly to control the use of e-cigarettes

The United States must act quickly to control the use of e-cigarettes

E-cigarettes: The lingering questions

E-cigarettes: The lingering questions