SPACE

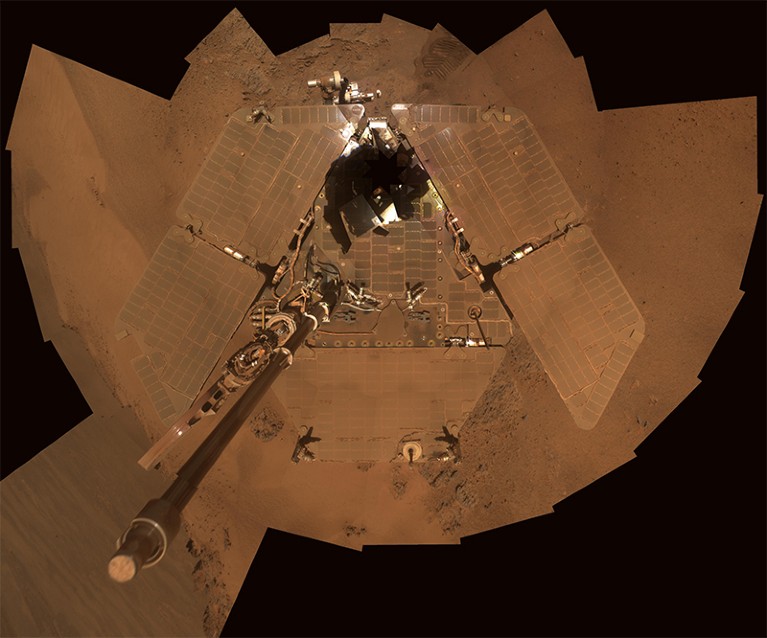

Done roving: Opportunity comes to rest After spending 15 years exploring 45 kilometres of the Meridiani Planum region of Mars, NASA’s Opportunity rover is officially dead, the agency said on 13 February. Opportunity had not communicated with its handlers since 10 June 2018, when a massive dust storm stopped the Sun’s rays from reaching the craft’s solar panels. Mission controllers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, tried unsuccessfully to contact the rover hundreds of times over the next several months, using different methods. Opportunity launched in July 2003 and landed in Meridiani Planum in January 2004, beginning what was planned as a 90-day mission but which far outlasted that goal. The rover ultimately discovered the most ancient habitable environment on Mars, and it now rests overlooking an area called, fittingly, Perseverance Valley. NASA’s Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in 2012 and is nuclear-powered, continues to explore, in Gale Crater.

NASA’s Opportunity rover took this self-portrait in January 2014; a thick layer of dust is covering its solar panels.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/Arizona State Univ.

Space harpoon A satellite has successfully tested a harpooning technique to clean up pieces of space junk. The RemoveDEBRIS satellite extended a 1.5-metre arm, erected a square, metal target and blasted a harpoon at it at a speed of 20 metres per second. The spear neatly pierced the target and nailed the test, demonstrating this type of capture for the first time. It was the third of four space-junk-clearing experiments for the RemoveDEBRIS project, which is led by the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, and the project team announced its latest feat on 15 February. Its first experiment tested a net-capture method and the second tested techniques for studying and navigating near space junk. In its final act, next month, RemoveDEBRIS will deploy a sail to drag itself lower in the atmosphere, where it will burn up. The satellite launched in April 2018.

HEALTH

Depression drug A form of the hallucinogenic party drug ketamine has cleared one of the final hurdles towards clinical use as an antidepressant. During a 12 February meeting at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Silver Spring, Maryland, an independent advisory panel voted 14 to 2 in favour of recommending a compound known as esketamine for use in treating depression. Researchers discovered ketamine’s antidepressant properties in the early 2000s, but it’s unclear how the drug works in the brain. Scientists know that it acts quickly to alleviate symptoms of depression — in a matter of hours, as opposed to weeks — and differently from other drugs approved to treat the condition. The FDA is expected to make a decision on esketamine by 4 March.

POLICY

EU digital rights European Union negotiators have agreed on a new copyright law to protect the rights of authors, publishers and creators in the digital age. The regulations were agreed on 13 February, and the European Parliament and EU member states are expected to approve them in April. They will grant publishers the right to seek compensation from online platforms such as Google and Facebook for the display of articles and other content. Such platforms will be allowed to use only short extracts, and share hyperlinks, free of charge. Major user-uploaded platforms and repositories will need to make “best efforts” to secure licences for uploaded content and to prevent users from posting unauthorized material. Text and data mining will be exempted from copyright restrictions, allowing researchers to harvest facts and data from sources to which they have legal access. Once the rules are formally approved, EU member states will have 24 months to implement them.

‘Dual use’ research A review of Australian export laws has pushed back against the government’s effort to tighten controls on technologies and research that might have dual military and non-military uses. Australian researchers, who were concerned that sweeping controls would restrict international collaboration, have welcomed the findings. Existing laws require academics working on research with dual use to apply for a Department of Defence permit before they communicate the work to anyone outside Australia. But the department wanted those laws, introduced in 2012 and amended in 2015, strengthened to reflect changes in national security risk. In a submission to a review of the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012, conducted by independent intelligence consultant Vivienne Thom, the defence department called for expanded powers to control the transfer of any technologies significant to defence, even those not on an existing list of controlled technologies. It also pushed to control the publication of papers related to these technologies. In her report, Thom recommends that the government work with universities, research agencies and industry to ensure any amendments to the laws do not unnecessarily restrict trade, research or international collaboration.

POLITICS

US budget deal US science agencies can breathe easier, after lawmakers scrambled to avert a government shutdown with hours to spare. A budget deal approved by the Senate and the House of Representatives on 14 February, and signed by President Donald Trump the next day, increases funding slightly for many science agencies compared with 2018 levels. The National Science Foundation’s budget grew by US$307 million, to $8.1 billion, and NASA’s funding reached $21.5 billion, a $764-million jump. The Environmental Protection Agency received $8.8 billion — $25 million more than it did in 2018 and $2.66 billion more than Trump had sought. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration saw its budget cut by roughly $500 million, to $5.4 billion. The funding legislation will keep the government running until 30 September 2019, the end of the current budget year.

Lawmakers in Congress are scrambling to pass funding legislation and avert a government shutdown.Credit: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

RESEARCH

Chinese censorship The controversial topic of the first babies born from gene-edited embryos was one of the most censored on Chinese social media last year, according to an analysis posted online last week. WeChatscope, a project run by researchers at the University of Hong Kong, tracks posts that have been deleted from public accounts on WeChat, China’s most popular social-media platform, which averages 500,000 users a day. The WeChatscope team has developed an interface that preserves deleted posts in a publicly accessible database, which the team uses to create a list of the most controversial topics. An analysis of WeChatscope’s 2018 data found that 41 posts on the twin girls born from gene-edited embryos were removed from WeChat, starting on 27 November — the day after Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui announced news of their birth in China. Other topics among the top ten most censored themes on WeChat last year include a physician jailed for criticizing traditional Chinese medicine, a major vaccine scandal, and allegations of sexual harassment against a professor at Peking University in Beijing.

EVENTS

Human gene editing The World Health Organization (WHO) has named the members of a committee that will develop global standards for managing research on human-genome editing. The panel, announced on 14 February, will be co-chaired by Margaret Hamburg, chair of the American Association for the Advancement of Science board of directors, and Edwin Cameron, a judge in the Constitutional Court of South Africa. The other 16 members also have expertise in law, bioethics or basic science. The committee will review the current state of human DNA editing, before advising the WHO on the oversight of research and future applications of the technique. It will first meet on 18–19 March in Geneva, Switzerland, to set its work plan for the coming 12–18 months.

Icebreaker detour A US icebreaker had to change course on its expedition to study Antarctica’s Thwaites glacier because of a medical emergency, the US National Science Foundation said on 15 February. One day before it was scheduled to reach Thwaites, the RV Nathaniel B. Palmer diverted to the British Antarctic Survey’s Rothera Station to drop off a person in need of care — a journey that is expected to take around a week. The detour will reduce the time that the cruise can dedicate to its scientific mission, during which researchers plan to collect sediment cores and map the sea floor around the front of the glacier. The cruise is a major part of the first field season for the UK–US International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a £20-million (US$25-million), 5-year effort to probe the rapidly changing glacier.

TREND WATCH

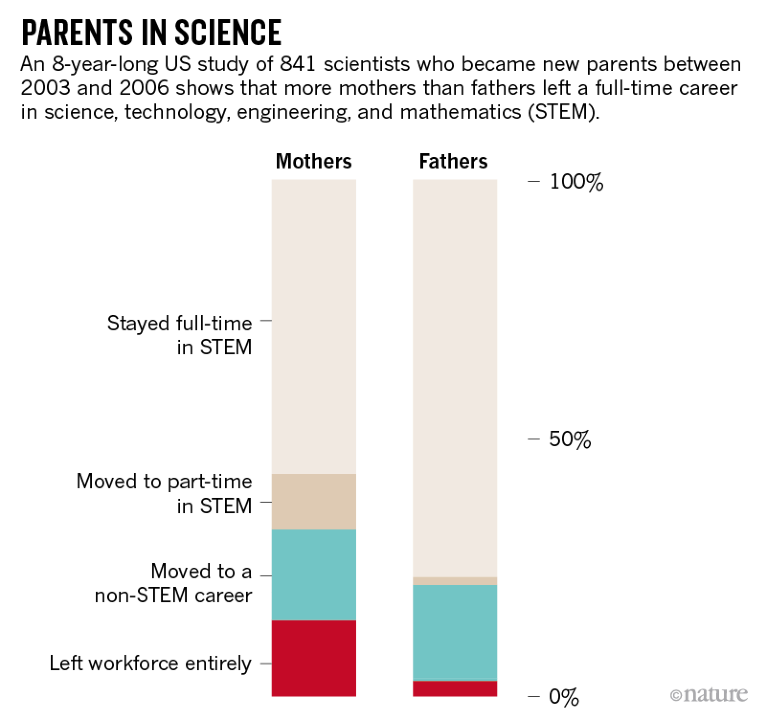

Some 43% of women with full-time jobs in science who become parents leave the sector or go part-time after having their first child. By contrast, only 23% of new fathers leave or cut their hours, according to a study of how parenthood affects career trajectories in the United States. The study, led by Erin Cech, a sociologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, used data provided by the US National Science Foundation to examine employment and household information. From the 2003 data set, the team picked child-free scientists in full-time employment and tracked their familial status in the next wave of the survey, in 2006. They compared two groups of scientists from this cohort — 841 who became parents during this period, and 3,365 who remained child-free throughout the study, which ran until 2010. The authors report that new parents were significantly more likely to leave a full-time science career than were their child-free colleagues. By 2010, just 16% of child-free men and 24% of child-free women had left a full-time science career — according to predictions from the data when the team controlled for confounding factors.

Source: Erin A. Cech et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810862116 (2019).Source: Erin A. Cech et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810862116 (2019).