Nations pride themselves on their research activities, using a variety of indicators to size up their scientific capacity and strength against those of close competitors. Spending on research and development, in which China is now second only to the United States, and publication output, in which China overtook the US in 2016, are closely tracked metrics.

These indicators have drawn global attention to the rapid rise of China and its challenge to the science leadership of the US. Our analysis suggests that China is on a trajectory to dominate citations also, due to tendencies to recognize the work of one’s fellow citizens.

On citations, the US has long cornered the market, accounting not only for the lion’s share but a disproportionate number of the top 1% most highly cited science and engineering papers. While Europe has been slowly gathering a larger share of the highly cited papers, the biggest growth has been from China, whose papers went from below to just above world average in the last decade. If the trajectory continues, China will outpace the European Union in its production of highly cited papers within the next decade or so.

Similarly, there remains a gap in terms of overall citations: the share of all cited references made to US papers, although decreasing steadily since the mid-1990s, remains slightly higher than that of the EU-28, and far above China, which accounts for only about 6% of all cited references.

This gap is likely to close, given the significant role that patriotism plays in referencing behaviour.

Self-referential

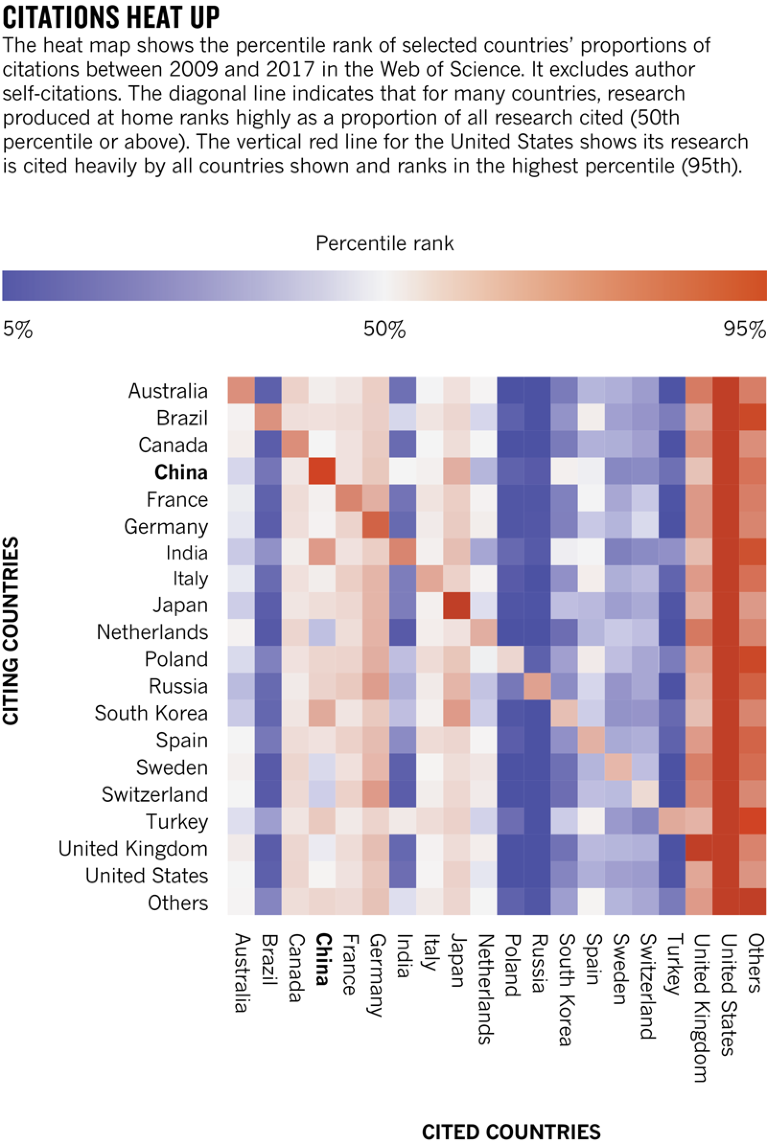

While many words have been devoted to the self-citing practices of individuals, less is known about the degree to which citations stay close to home at the country level. Although the US and United Kingdom garner a large share of global citations, all countries cite themselves disproportionately. This remains true even when controlling for author-level self-citations.

For the EU, as an example, 40% of all references made and citations received are from other European countries. The US, on the other hand, has tended to reference itself much more than the EU: between 1980 and 1996, 60% of references in US papers were to other US papers. However, the US is increasingly citing outside the country and, consequently, receiving a lower share of its overall citations from itself. US self-citations fell steadily from 41% to 33% between 1980 and 2013, though they’ve since gained a few percentage points to 37%.

While China’s self-references has remained low during the period of assessment, at under 20% of all paper references, Chinese researchers are increasingly citing work from other Chinese researchers. This has resulted in an increase in country self-citations from around 30% in the 1980s to 47% in 2015. China’s self-citations as a share of total citations surpassed that of the US in 1999 and is now greater than the US self-citations by 10 percentage points.

The citation payoff is obvious. These trends reveal the tight coupling between paper production and citation: as a country increases production, and therefore a supply of potential references, the country is likely to rely on this capacity and occupy a greater share of the citation space.

Over the past two decades, China has experienced tremendous growth in terms of research investment and production, leading to a larger share of citations. China’s increased production is likely to result in a dominance of citations in coming years, and is both a sign and consequence of its rapid maturation as a force in science.

All eyes on the prize

All eyes on the prize

Ongoing challenge

Ongoing challenge

Yielding results to feed a people

Yielding results to feed a people

China’s place among the stars

China’s place among the stars

Small science grows large in new hands

Small science grows large in new hands

Engineering a biomedical revolution

Engineering a biomedical revolution

Strong spending compounds chemistry prowess

Strong spending compounds chemistry prowess

Quality deficit belies the hype

Quality deficit belies the hype

Partner content: Make your mark in the city of makers

Partner content: Make your mark in the city of makers

Partner content: A non-stop route to collaborative discovery

Partner content: A non-stop route to collaborative discovery

Partner content: Melbourne, Victoria — Number 1 in Australia for medical research and biotechnology

Partner content: Melbourne, Victoria — Number 1 in Australia for medical research and biotechnology