Age Old Cities Arab World Institute, Paris. Until 10 February 2019.

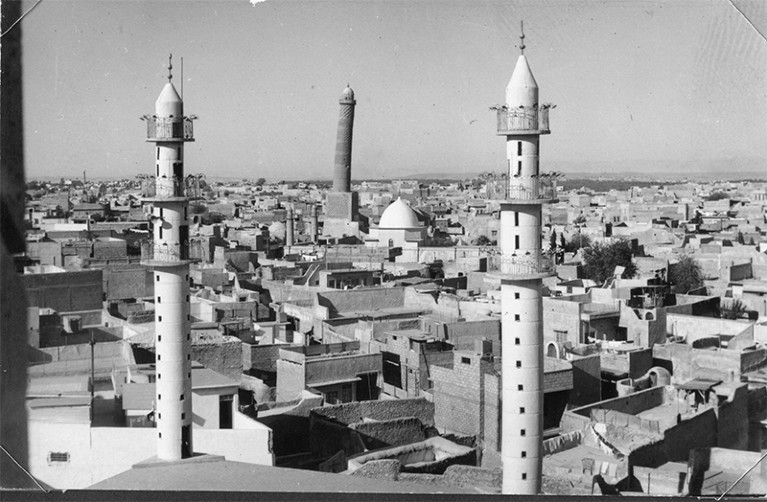

For more than 800 years, a minaret dominated the skyline of Mosul, Iraq. Nicknamed al-Hadba, or ‘the hunchback’, because of its 3-metre tilt, it belonged to the Great Mosque of al-Nuri, commissioned in the twelfth century. Mosque and minaret were reduced to rubble after Islamist terrorist group ISIS took the city in 2014.

Today, both can be seen in an exhibition at the Arab World Institute (AWI) in Paris. The reconstruction is digital, not physical, but the translation of the former into the latter is under way in now-liberated Mosul, thanks to a 5-year, US$50-million rebuilding project announced this year. The exhibition aims to show how digital technologies are redefining rescue archaeology and contributing to the preservation of our past.

The leaning minaret (centre) of the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Mosul, Iraq.Credit: APDF – Mosul Fund

The Monumental Arch of Palmyra in Syria, destroyed by ISIS in 2015, was recreated first digitally and then in Egyptian marble — in which form it is currently touring the globe. That initiative was criticized for stripping the arch of its context. This exhibition avoids that error, and gives only a nod to the arch, the best-known product of digital archaeology so far.

The show focuses on four sites of historical importance in the Arab world: Mosul and Palmyra, along with Aleppo in Syria and Leptis Magna in Libya. All have seen empires rise and fall; all sit atop layers of rich archaeological material. Some are also, as this exhibition reminds us, living cities.

The Age Old Cities exhibition displays a 3D reconstruction of Mosul.Credit: Thierry Rambaud/IMA

On a giant screen in the first room, the Old City of Mosul is projected in three dimensions. A fly-over view shows how ancient monuments are embedded in urban fabric, and how badly both have been damaged. Before our eyes, the monuments are rebuilt, virtually. Paris-based start-up Iconem partnered with the AWI to create these dense projections by combining data from aerial images taken by drones, pictures taken at ground level using a boom, and old photographs of the monuments before they were destroyed. The drones enabled Iconem’s team to penetrate cities before they had been de-mined.

There are no physical objects in the exhibition. Through video documentaries and interviews, visitors learn that until very recently, several religious groups lived side by side in Mosul. One of the symbols of the city’s multiculturalism was the tomb of Jonah — a prophet for Jews, Christians and Muslims — who was buried in the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, where Mosul now stands. After the city was liberated in 2017, Iraqi archaeologists discovered that ISIS had destroyed Jonah’s tomb and dug a network of tunnels beneath. Exploring these, they stumbled on the remains of an Assyrian palace. Meanwhile, the previously hidden remains of a synagogue were discovered in the rubble of the Jewish Quarter.

In a 3D reconstruction, a damaged souk in Aleppo, Syria, rises from its own rubble.Credit: ICONEM/DGAM

Aleppo’s story is different. The damage there was collateral, the fallout from fighting between the Syrian regime and rebel forces between 2012 and 2016. At the centre of old Aleppo lies a magnificent thirteenth-century citadel, itself built over remains from the Roman period or even earlier. Syrian troops made the citadel their base; from here they bombarded the rebels in the city beyond, so it came through relatively unscathed. The city’s souks, on the other hand, were badly damaged. Commerce is Aleppo’s beating heart, and the marketplaces are being rebuilt. Exhibition visitors can wander virtually through them as they once were.

The 3D reconstructions of Palmyra and Leptis Magna face each other across a room, because of what they have in common and what sets them apart. Both are purely archaeological sites, not embedded in modern cities; but ISIS destroyed 80% of Palmyra, although it mostly spared the site’s Roman theatre, where the group staged its executions. The lesser-known Roman site of Leptis Magna — dubbed the Rome of Africa — has been looted and neglected, and is threatened by rising seas. The pairing makes a larger point: war isn’t the only threat to our material heritage, nor the only one to which digital reconstructions provide at least a partial response. Donning a headset, visitors can become virtual-reality tourists and see that for themselves.

The Roman theatre in Leptis Magna, Libya, reconstructed from photographs.Credit: FDD, ICONEM/MAFL/DOA

There is one glaring omission that makes this poignant exhibition even more timely. No mention is made of the Yemeni sites damaged by Saudi bombs, such as the almost-4,000-year-old Marib Dam. The AWI is partly funded by Saudi Arabia. And the omission underlines the fact that both the decision to destroy and the decision to rebuild are political — as Warsaw, Coventry and Dresden, ravaged in the Second World War, know only too well.

UNESCO’s troubled drive for peace through science and culture

UNESCO’s troubled drive for peace through science and culture

The wonder of the pyramids

The wonder of the pyramids

Save Libyan archaeology

Save Libyan archaeology