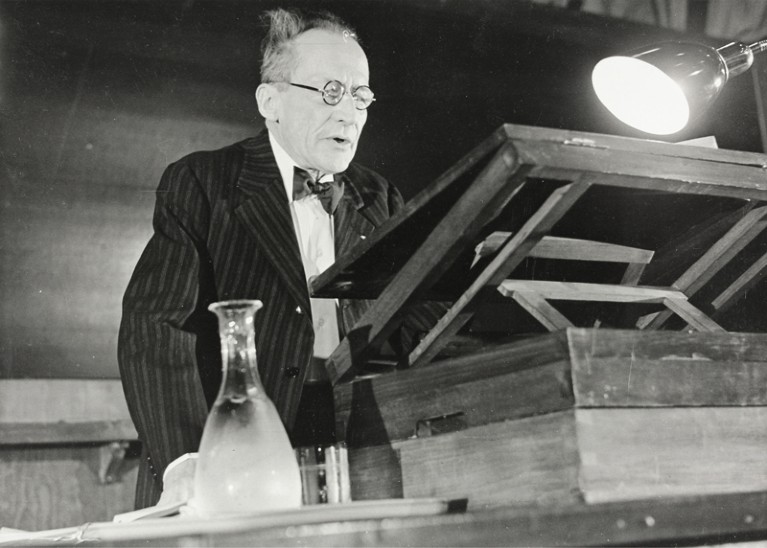

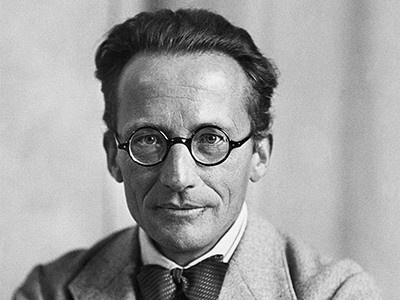

Physicist Erwin Schrödinger helped to change attitudes to molecular biology.Credit: akg-images/IMAGNO/Votava

In the winter of 1943, the physicist Erwin Schrödinger invited the Dublin public to hear him deliver a series of lectures he described as “difficult” and that “could not be termed popular”. Some 400 people were undeterred and were among the first to hear Schrödinger offer his views on how physics could shed light on the puzzling ability of living organisms to maintain molecular order and organization in the face of what seemed to be the randomizing forces of nature.

Seventy-five years on, some of his ideas remain difficult — controversial even. But they are popular, and are once again drawing people to the Irish capital. Trinity College Dublin will this week host ‘Schrödinger at 75 — The Future of Biology’, at which a stellar cast of speakers will consider the future of disciplines ranging from ageing and plant science to infectious disease and consciousness.

Schrödinger’s cat among biology’s pigeons: 75 years of What Is Life?

Schrödinger’s lectures were collected into what he called his “little book”, What Is Life?, published in 1944 (see Nature 560, 548–550; 2018). Some consider it one of the most influential scientific books of the twentieth century.

The book attracted scientists from other fields to the study of genetics and the molecular mechanisms of life, among them physicists Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins and Seymour Benzer, chemist Gunther Stent and zoologist James Watson. But can the ideas in this slim volume really supply sufficient motivation for such a diverse programme?

Critics have rightly argued that the book was neither particularly original nor up to date. It limited itself mostly to a discussion of the molecular basis of inheritance through chromosomes. Here Schrödinger made the auspicious proposal that the genetic material is an “aperiodic crystal”: a structure with a specific but not periodic arrangement of atoms, encoding information that somehow guides the development of the organism. That vision resonated with Crick and Watson as they contemplated the structure of DNA in the following decade, but it wasn’t wholly original. As to how the genetic machinery works, Schrödinger could only point out that it seems to suspend the second law of thermodynamics, which states that total entropy must increase.

The impact of What Is Life? lies more in its spirit than its substance. Schrödinger presented the problem of life as a puzzle posed to no single discipline. And his timing was perfect: biology was already changing from a largely descriptive, historical and organismal science to a mechanistic and microscopic one. This cross-disciplinary relevance applies equally to the topics addressed at the Dublin meeting. The physical-sciences content of artificial intelligence and complex systems is obvious, but understanding of (say) cognitive neuroscience, learning and memory and infectious disease can also benefit from wide-ranging expertise: for example, from the study of network topologies, the thermodynamics of information, and ergodicity (how widely a dynamic system explores its available states).

Happily, chemistry is welcomed to this table too. That subject, after all, is what biologists relied on mid-century to probe and better understand DNA, enzymes and cell signalling. The subsequent emergence of molecular biology, due in large part to some of those inspired by What Is Life?, means that whether Nobel prizes get assigned to ‘chemistry’ or ‘physiology or medicine’ is now as arbitrary as whether Nobels in nuclear science in the early twentieth century were awarded in chemistry or physics.

What Is Life? made the case that profound questions about the natural world aren’t owned by any academic discipline. Indeed, the Dublin meeting could have gone further by embracing Schrödinger’s epilogue on determinism and free will, which invoked philosopher Immanuel Kant and Hinduism (and spoilt the book’s chances of publication in devoutly Catholic Ireland). Some eyebrows were raised at this material, but Schrödinger’s friend Albert Einstein would have seen nothing amiss in it. Philosophers, ethicists, poets and theologians also have a stake in the future of life. Perhaps they will be invited to the centenary.

Schrödinger’s cat among biology’s pigeons: 75 years of What Is Life?

Schrödinger’s cat among biology’s pigeons: 75 years of What Is Life?