X, Y & Z: The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken Dermot Turing The History Press (2018)

Alan Turing’s crucial unscrambling of German messages in the Second World War was a tour de force of codebreaking. From 1940 onwards, Turing and his team engineered hundreds of electronic machines, dubbed bombes, which decrypted the thousands of missives sent by enemy commanders each day to guide their soldiers. This deluge of knowledge shortened the war. Bletchley Park, UK — the secret centre where it all happened — rightly gained its place in history. But as with all breakthroughs, many more people laid the foundations.

In his book X, Y & Z, Dermot Turing, the great mathematician’s nephew, tells the gripping story of a band of Polish mathematicians who figured out much about how German Enigma encoding machines operated, years before Alan Turing did. The Poles shared their secrets with French and British intelligence services before and during the Second World War — the letters X, Y and Z were shorthand for the French, British and Polish codebreaking teams, respectively.

The author’s research is painstaking. After the war, military documents were scattered across Europe, and key French records were declassified only in 2016. Many original Polish papers were destroyed, but the mathematicians’ families have shared personal letters. Turing unearths a remarkable tale of intellect, bravery and camaraderie that reads like a nail-biting spy novel.

Polish skills in cryptography and radio engineering came together during the 1920 Russo-Polish War. Signallers decoded a telegram from Red Army military commander Joseph Stalin, which indicated that an attack on Warsaw was imminent. Jamming the Russians’ radio communications bought enough time to secure and save the city. Maksymilian Ciężki and Antoni Palluth were among those signallers. After the 1920 conflict, Ciężki became leader of a radio-intelligence unit. Palluth set up a business making electronic equipment, including radios the size of a credit card for Polish secret agents.

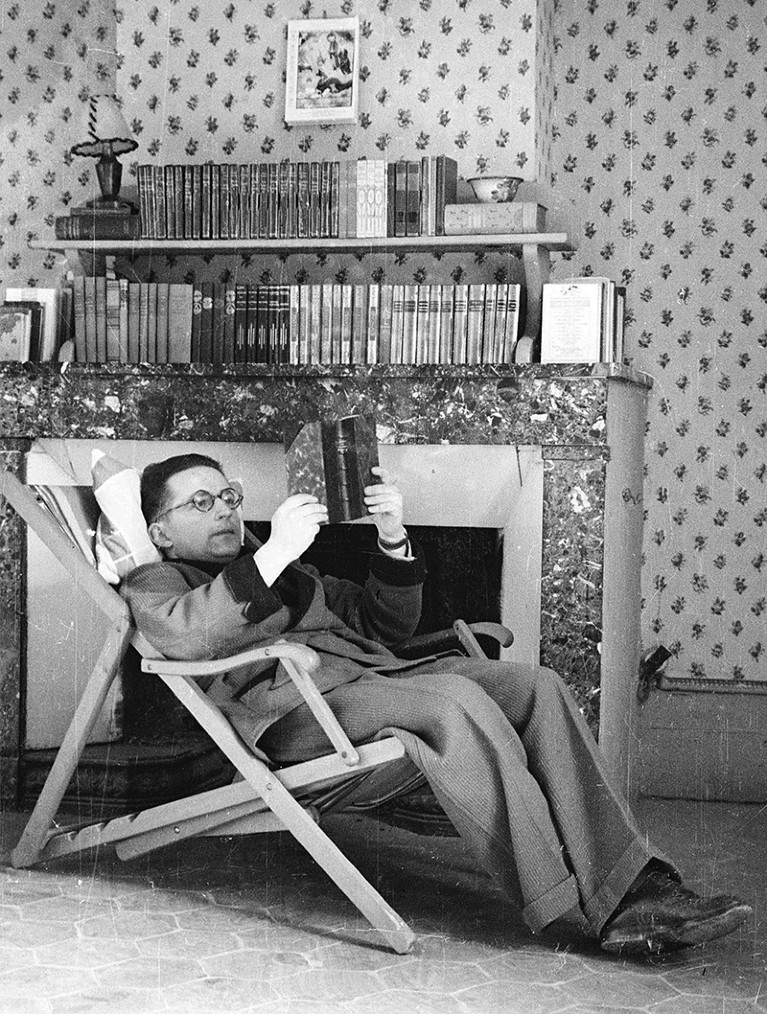

Polish codebreakers Antoni Palluth (left) and his cousin Sylwester stand in front of a chart of North African military operations in 1942, when they were working with French intelligence officer Gustave Bertrand in southern France.Credit: Anna Zygalska-Cannon

In 1926, the German navy began to send messages that were scrambled in a more random way, making them almost impossible to decipher. They were encoded using the typewriter-like Enigma machine. The keyboard was wired so that typing one letter lit up a different one in a set of bulbs on top. Rotors altered the path of the electric circuit with every keystroke. The machines were commercially available but modified for German military use. Without knowing the precise setting of a machine, there was no way to unpick the code.

The book tells how Ciężki hired a group of mathematics students to crack the problem. They worked quietly in basements and in a bunker deep in the woods. Marian Rejewski, an alumnus of Poznań University in Poland, was one. At the helm was Gwido Langer, a Pole who had worked in radio intelligence for the Austrian army.

Meanwhile, in France, Gustave Bertrand headed the equivalent unit. The French had a more conventional approach to gathering information: good agents, clandestine meetings and generous pay-offs. Bertrand managed two formidable spies. Rudolf Stallmann — code name Rex — was a German card-sharp who had posed as a baron to fleece casino-goers; he picked up languages and people with ease. Rex recruited Hans-Thilo Schmidt, or Agent Asche, whose brother was a colonel in the German army. Schmidt supplied cases of military documents to the French, which Rex received and Bertrand and his colleagues photographed in hotel bathrooms.

Bertrand built up a network for sharing intelligence, including with Poland and the United Kingdom. In 1931, he agreed to supply Langer with German military documents if the Poles would pass back decrypted German messages. One of those documents, passed on by Schmidt, was a manual for Enigma.

Polish mathematician Marian Rejewski relaxes in the French chateau where the codebreakers were working to crack the Enigma machine codes in 1942. Credit: Anna Zygalska-Cannon

Langer, Ciężki and Rejewski leapt on it. They discovered that a panel added to the front of the machine altered the settings, although they still could not tell how the device was wired. They set about collecting coded messages and applied their wits to find clues. Sometimes the senders made telling mistakes. The German soldiers might use simple sets of three letters, such as QQQ, to broadcast the settings to the receiver. Occasionally, the messages could be guessed: for instance, they often said maschine defekt.

By 1936, in the run-up to war, the German military was tightening its communications. In October that year, the senders began to reset the Enigma machines daily. Dermot Turing credits another Polish mathematician, Jerzy Różycki, with realizing that this altered the frequency of letters, revealing extra information. The team developed tools to work through the hundreds of permutations, including punched cards and a mechanical device with rotors that mimicked Enigma, which, for uncertain reasons, the team called a bomba. Both concepts were later used and developed by Alan Turing.

Bertrand fed this information back to Britain’s codebreakers, who come across in the book as humorous but aloof. They called the French dispatches — stamped TRÈS SECRET in red — scarlet pimpernels. In late July 1939, just over a month before the German army marched into Poland, Bertrand arranged for the respected British cryptologist Dillwyn ‘Dilly’ Knox (who was already working on Enigma at Bletchley) to meet Langer’s team near Warsaw. The Poles wanted to pass on their knowledge. Initially angry that they had beaten him to it, Knox later sent the Poles a silk scarf printed with a horse-racing scene to concede that they had won.

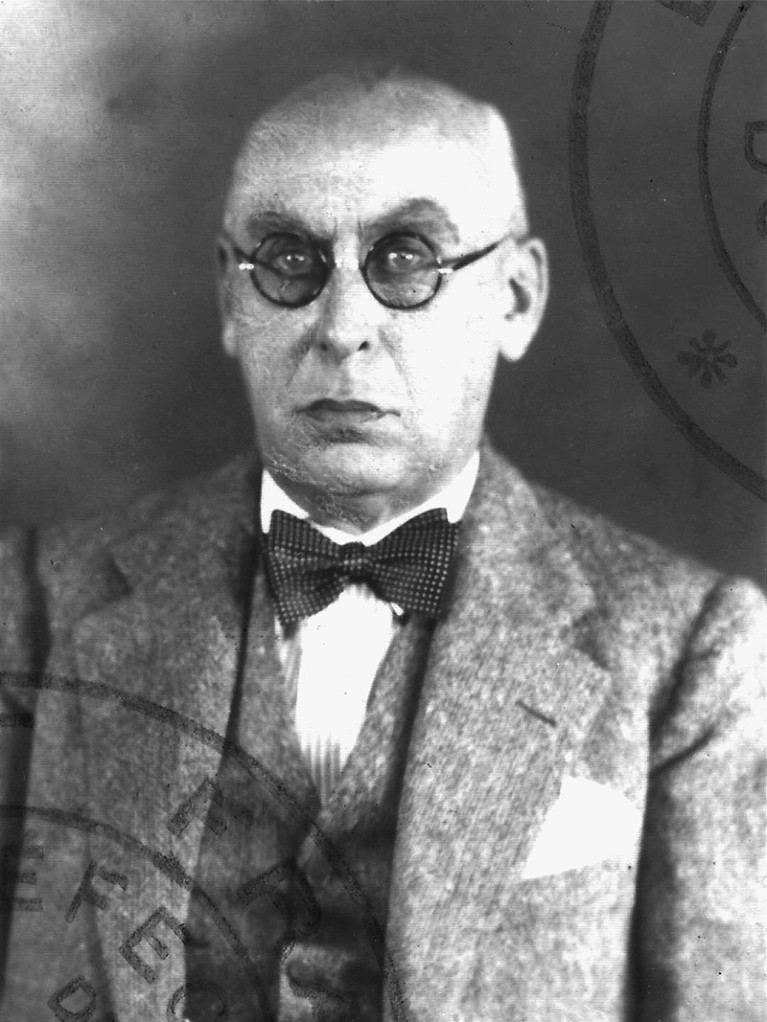

Rudolf Stallmann — code name Rex — was a German card-sharp who spied for the French intelligence service. Credit: Christie Books

The British immediately ramped up codebreaking efforts at Bletchley Park; within a few months, Alan Turing had re-engineered the bombes to work more quickly. The Polish insights saved him a year of work.

When war broke out, the Polish radio-intelligence unit was wound up. The codebreakers buried their notes and machines and fled. Some ended up in Algeria, the rest in France working for Bertrand, who had set up a radio-intelligence group in a chateau in southern France. In breathtaking passages, the book reveals how most of the Polish codebreakers made it through the war, tapping into the French Resistance and dodging Germany’s military-intelligence services and secret police when France became occupied. As valuable assets, the codebreakers were not allowed to fight. Touching photographs in the book show them joking with each other and spending time with girlfriends amid the devastation.

Eventually, Ciężki and Langer were arrested and interned in the Sudetenland (now part of the Czech Republic). After the war, they settled in Scotland. Palluth was killed in Germany in 1945, when an aeroplane factory in which he was working at Sachsenhausen concentration camp was bombed. Bertrand artfully played all sides. Avoiding becoming a double agent, he ended up a general. In 1972, he wrote a popular French book about Enigma, and so the story of X, Y and Z and Bletchley began to seep out.

Dermot Turing’s vivid and moving account sets the record straight.

Ancient dreams of intelligent machines: 3,000 years of robots

Ancient dreams of intelligent machines: 3,000 years of robots