The mushroom cloud from the first hydrogen-bomb test, at Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, in 1952.Credit: Corbis via Getty

Ape and Essence Aldous Huxley Harper & Brothers (1948)

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 shocked the world. More than 70 years on, these events have not been repeated — evidence that it was the United States’ temporary nuclear monopoly that made them possible. Yet few observers in the immediate postwar years foresaw the development of an uneasy nuclear truce, enforced by the certainty of mutual destruction. Fears of an arms race culminating in nuclear war were widespread. Such fears have now re-emerged, with North Korea’s burgeoning arsenal and the United States’ abrogation of its agreement with Iran.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, who directed the development of the first bombs, was among those who feared nuclear conflict, and worked for international control after the Second World War. Physicist Richard Feynman (whom I interviewed for my 1987 book The Making of the Atomic Bomb) recalled sitting in a bar in New York in 1946, watching the crowd passing outside and thinking: “You poor fools, you have no idea that in a few more years you’ll all be dead.” Aldous Huxley seems to have leapt to the same conclusion in his hybrid novel and film scenario Ape and Essence, published 70 years ago.

The prolific novelist and essayist had been formulating his thoughts on the bomb since the end of the war. In 1947, Huxley published the extended essay ‘Science, Liberty, and Peace’, a prelude to the novel. There, he wrote that the power-hungry and nationalistic “boy-gangster” in us all would easily prevail over the reasonable adult, exulting: “Press a few buttons and bang! the war to end war will be over, and I shall be the boss of the whole planet.” Huxley knew better. If more than one nation had such weaponry, he believed, the outcome of “the war to end war” would be world-scale destruction. And because that would be a kind of singularity, it seemed to him that almost anything might follow.

Ape and Essence is Huxley’s imagining of a post-nuclear world. The title is from William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure: Isabella speaks of the proud man’s “glassy essence, like an angry ape”, which “plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven/As make the angels weep.” The angels have flown in Huxley’s novel, set in what remains of Los Angeles, California, in 2108 — a century after a third world war, which would have taken place around now, in Huxley’s fictional timeline.

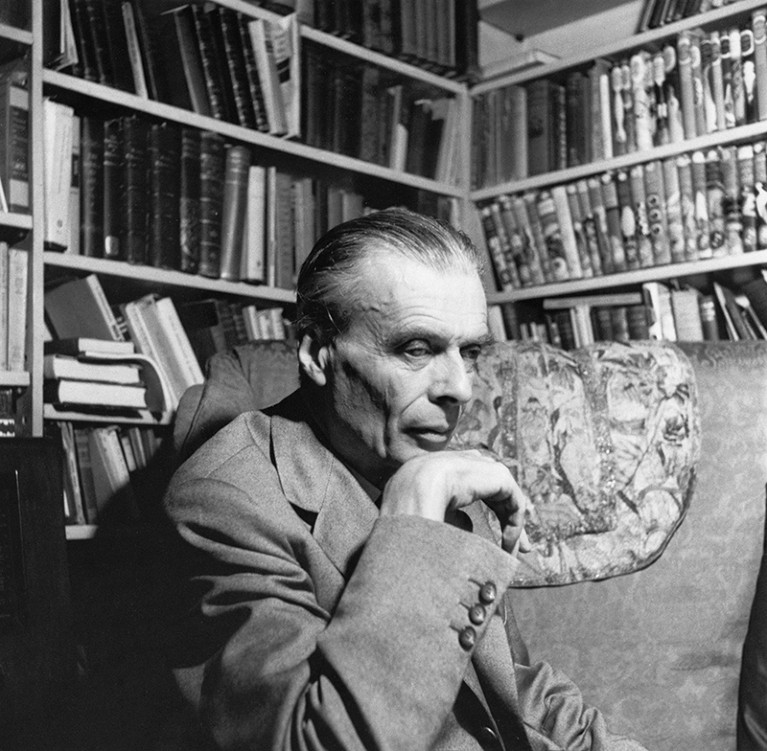

Aldous Huxley in the 1950s.Credit: Age Fotostock/Alamy

In one of the book’s set pieces, intelligent baboons fight this twenty-first-century war, with scientific luminaries (Michael Faraday and two opposing Albert Einsteins) as leashed mascots. So much for scientists, Huxley insinuates — “good, well-meaning men, for the most part. But ... they ceased to be human beings and became specialists.” Of the two opposing cultures described by scientist and novelist C. P. Snow in 1959, Huxley was clearly on the side of the humanities, as if locked in debate with his distinguished scientific kin — his biologist brother Julian, physiologist half-brother Andrew and zoologist grandfather Thomas Henry, known as Darwin’s bulldog.

Having introduced the baboons, Huxley kills them off: it’s a second false start to the novel’s stuttering story, a metafictional concoction as multilayered as an onion. The first storyline sees two screenwriters tracking down a legendary colleague, only to find him dead. The deceased’s abandoned screenplay (I suspect one of Huxley’s own unsold efforts, repackaged) is the book’s centrepiece. It is here that the baboons rise and fall. The script then moves on to an improbable love story set in the world of an irradiated rump of humans who survived the war but have forgotten how to make things. They live by scavenging leftovers from the pre-war days, burning books for heat and assigning crews to rob old graves of suits and jewellery. Eunuch priests of the devil-figure Belial squat at the top of the caste system in this stunted world, dominating a society of near-slaves.

Ape and Essence parallels Huxley’s 1932 Brave New World (see P. Ball Nature 503, 338–339; 2013), yet offers an even darker vision. A young botanist, Alfred Poole, has arrived by ship from New Zealand, which survived the atomic war and is now exploring what’s left of the world. So, as with Brave New World’s Savage, a Candide-like hero appears from outside society and finds himself appalled. And what appals both heroes is the indiscriminate sexuality that the society’s leaders encourage to replace family and human love.

The twist this time, as Huxley wrote to his fellow screenwriter Anita Loos, is that “the chief effect of the gamma radiations [has] been to produce a race of men and women who don’t make love all the year round, but have a brief mating season”. This manifests as mass gropings; any progeny deemed too monstrous, the result of radiation-damaged genes, are then slaughtered on Belial Eve. (Huxley probably knew that Hermann Muller had received a Nobel prize in 1946 for the discovery that X-rays can cause mutations.) The ceremony, called the Purification of the Race, mimics the blood sacrifices of the Aztecs. It also alludes to eugenics, the British–American pseudoscience embraced by Adolf Hitler.

What all this sexualized barbarity has to do with nuclear war isn’t clear. Born in 1894, Huxley brought a scolding Victorian sensibility to the loosened morals of the war-torn twentieth century, excoriating its hedonism in satires and science fiction. Sun-drenched, beauty-obsessed southern California, where he lived and worked from 1937 until his death in 1963, proved the ideal locale for his dystopias: a seeming paradise that was also the end of the frontier.

Appropriately enough, Ape and Essence culminates in a Hollywood happy ending, at least for Poole and Loola, the young woman he falls in love with. The lovers escape to northern California, where a colony of “hots”— hold-outs with conventional sexuality — are cobbling together a new life. However disdainful Huxley might have been of our core boy-gangsters, in the end, he was too humane for a truly relentless apocalypse: his dystopias had escape hatches. Would that the same could be said of a real nuclear war.

In retrospect: Brave New World

In retrospect: Brave New World

In retrospect: Gulliver's Travels

In retrospect: Gulliver's Travels

Dreaming of the bomb

Dreaming of the bomb

The making of a bomb scientist

The making of a bomb scientist