Teeth Wellcome Collection, London. Until 17 September.

Teeth are weirdly emotive parts of the human anatomy. Proudly displayed in smiles, essential to healthy diets, they provoke anxiety when diseased or deformed. Their upkeep is haunted by the spectre of the dentist’s chair and its malign accompaniment, the whine of drills. Dentistry, and by implication odontology, thus treads a fine line between being fraught and fascinating.

London’s Wellcome Collection explores that nexus with gusto in Teeth, an exhibition inspired by medical historian Richard Barnett’s 2017 history of dentistry, The Smile Stealers. It’s a compact show that punches above its weight. In one room, curators cover the gamut, from historical artefacts to the future of dentistry — and difficult truths about the role of social inequality in dental care.

An amulet made from moles’ feet, worn to protect against toothache.Credit: SSPL

I was greeted by A Very Shorte and Compendious Methode of Phisicke and Chirurgery, a 1642 book of cures by Jane Jackson that features recipes to whiten teeth and cure toothache. At the time, many believed that worms caused tooth decay. In a case are amulets made from moles’ feet, created around the start of the twentieth century but similar to those thought (by first-century ad Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, among others) to protect against toothache. Round a corner is a hard, spare Victorian-era wooden barber’s chair. Barbers of the time commonly dealt with grisly medical procedures such as pulling teeth — and even amputations. This contrasts sharply with the modern dentist’s chair on show, used to highlight the trend towards high-tech scans and 3D-printed models of an individual’s dentition.

The exhibition is not always as grim — or gross — as its topic might suggest. There are, for instance, letters to and from the parental ‘tooth fairy’. (“OK, five pounds … just this time. Share it with your sister,” capitulates one weary-sounding fairy.) A section on the use of anaesthetics recounts an early public experiment in 1845, when US dentists Horace Wells and William Morton tried to demonstrate the effectiveness of nitrous oxide in blocking the pain of having a tooth pulled. The dose was too low, and the volunteer screamed in agony, leapt up and started a brawl with his dentists. (A follow-up using ether proved more successful.)

A 1912 booklet advertising Goodall’s Dental Institute in London.Credit: Wellcome Coll.

A major culprit in decay was, of course, sugar, a product of globalization and the slave trade. In the late sixteenth century, a German visitor to Queen Elizabeth I’s court noted that the monarch had black teeth, “a defect that the English seem subject to, from their great use of sugar”. But consumption of the sweet stuff was initially confined to the super-rich. Two centuries after Elizabeth, the habit became more widespread, and fixes for the inevitable rot and tooth loss sprang up. It’s therefore not surprising that a hint of the macabre emerges in this show.

That is notable in a section on technologies devised to replace lost teeth. Efforts to fashion dentures from hippopotamus ivory or even porcelain failed to mimic the durability and appearance of the human tooth. Later, dentists resorted to what were known as Waterloo teeth — harvested from corpses — for use in dentures. These were named after the momentous 1815 Battle of Waterloo in present-day Belgium, whose 50,000 dead supplied plenty of material.

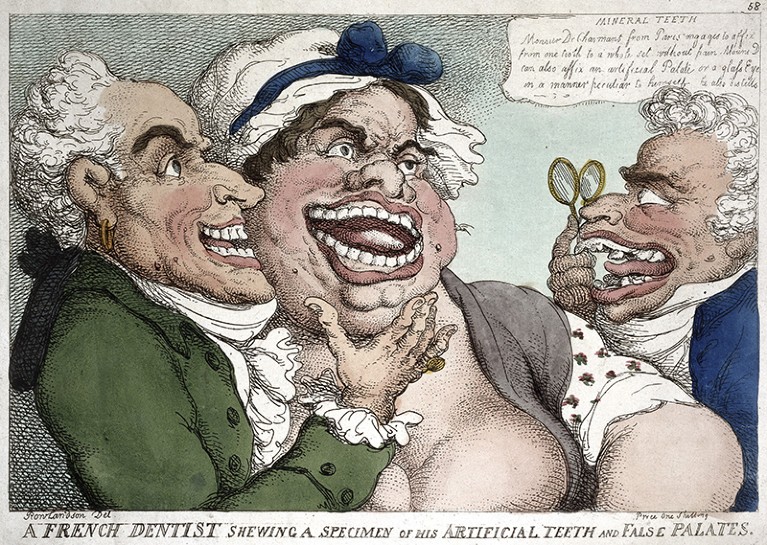

An 1811 engraving by Thomas Rowlandson satirizes the use of dentures.Credit: Wellcome Coll.

Understandably, extracting teeth from dead bodies made some squeamish. Eighteenth-century Scottish surgeon John Hunter experimented with an alternative to dentures: transplanting teeth from living donors. The fruit of a bizarre early experiment is on display — a human tooth transplanted into the comb of a cockerel. Hunter considered the work a success, thinking that the tooth had actually integrated itself into the comb. Modern examiners have since concluded that he merely did a good job of firmly shoving it in. Yet transplantation thrived for a few decades, says curator Emily Scott-Dearing. Five transplanted teeth are on display, as is one of the most chilling sights in the collection: a cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson from around 1790, depicting an impoverished child in pain after having a tooth yanked to fill out the smile of a wealthy woman.

The role of wealth disparity in shaping human dentition is also starkly revealed in two nineteenth-century human skulls on loan from the Museum of London. One comes from a woman, Bampton Taylor, who was buried in a ‘quality’ coffin; it features an expensive dental bridge with Waterloo teeth, held in place by platinum wire. The other, an anonymous specimen from a graveyard linked to a debtors’ jail, reveals rotten teeth encrusted with jagged mounds of plaque. As a 2017 report by Britain’s Nuffield Trust revealed, such dental inequity persists.

Aluminium false teeth made from a downed Japanese plane by British prisoners of war in Burma during the Second World War.Credit: Philip Gierlinski/BDA Museum

Later in the show, a striking set of dentures is on display, forged from aluminium taken from a Japanese plane downed during the Second World War. Fashioned by UK Royal Air Force prisoners of war in Burma, they took the place of a set knocked out by prison guards. This, and the other intimate stories in this show, underline the primal role of teeth in human health — and the power of human ingenuity once they are lost.

Evolution with teeth

Evolution with teeth

The war on germs

The war on germs

Something to chew on

Something to chew on