Damage to crops and infrastructure make a compelling economic case for action on climate change.Credit: Ricardo Arguengo/AFP/Getty

Published in 1991, an academic paper called ‘To slow or not to slow: the economics of the greenhouse effect’ is seen as the first attempt to model the economics of global climate change (W. D. Nordhaus Econ. J. 101, 920–937; 1991). Written by the economist Bill Nordhaus, the 18-page study assessed the costs of acting on emissions and the estimated costs of not doing so, and concluded that it was better for the economies of the world to try to address the problem than simply to give up and take the consequences.

Economists and analysts around the world have repeated the exercise many times, most prominently with the British government’s Stern Review in 2006 (N. Stern The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007). Almost all agree with the original conclusion: it will be much cheaper to spend the money on trying to curb emissions than to pay for the impact of the resulting climate change. But how much cheaper? There’s the rub.

Read the paper: Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets

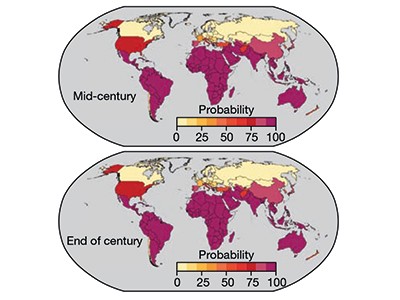

A study in Nature this week offers the latest and most comprehensive attempt to address this question. Marshall Burke and his colleagues modelled the impact of historical temperature changes on the gross domestic product (GDP) of 165 countries between 1960 and 2010. They then ran the model to the end of this century to plot what would happen to GDP according to how much average temperature rise was expected. The results show that greater action to curb temperature will bring greater economic benefits — which are, in reality, avoided damages, measured as the impact on GDP.

Specifically, there is a 75% chance that keeping global warming to a 1.5 °C rise — an aspiration of the Paris climate treaty — will leave the world better off than letting it run to a 2 °C rise. The probable savings: a cumulative US$20-trillion increase in world GDP by the end of the century. (Global GDP in 2016 was about $76 trillion.)

It’s fair to say that not all of the world’s economists and climate-policy wonks will be content to take the conclusions of the study at face value. Details matter, not least — as with all models — the kinds of assumptions made and data used. The Stern Review, for example, was quickly queried by economists who criticized the way in which it borrowed from the insurance industry and placed great importance on the needs of future generations, who are usually discounted in models of economic impact because it is assumed that they will be considerably richer and so better able to deal with problems than are today’s generation.

Read the News & Views: The cost of a warming climate

In that spirit of debate, this week we also publish two — conflicting — opinions on this study in a News & Views Forum. It provides a glimpse of the debate already raging in the economics community. One point of contention is how fair it is to simply extrapolate from past trends into the future. As finance experts are keen to point out, past performance is not always a reliable guide to future yields, and in this case it could be that the people of the future will find ways to adapt to a changing climate that are not accounted for in the model. Such adaptation — the development and widespread introduction of drought-resistant crops, for instance — would offer a significant saving, because food prices would not increase so dramatically if harvests are protected.

Another feature of the new model is that it assumes that climate change, and the extreme weather it is expected to bring, will have a compound impact on the rise of a nation’s GDP. Thus, a devastating storm or washed-out summer would affect not just that year’s economic performance, but also its performance in subsequent years. Previous studies have taken a more optimistic view that any damage could quickly be compensated for.

There is a more fundamental issue, too. Just how reliable is GDP as a metric? Famously, it assumes that the market price of goods and services fully reflects the costs of their production and use. And the economics of climate change don’t always do that: the price of fossil fuels, for one, doesn’t take account of the costs associated with future warming.

Like all models, these economic projections will be argued over, worked on and ultimately improved. Scientists can gather the data to help that process, for example by expanding studies of the regional effects of climate change to poorer nations that are already bearing the brunt of the physical and economic impacts. Meanwhile, the arguments for acting on greenhouse-gas emissions, already many and varied, just got a little stronger. Our burning of fossil fuel is writing cheques that our economy can’t afford to cash.

Read the paper: Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets

Read the paper: Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets

Read the News & Views: The cost of a warming climate

Read the News & Views: The cost of a warming climate

Can the world kick its fossil-fuel addiction fast enough?

Can the world kick its fossil-fuel addiction fast enough?

Climate talks are not enough

Climate talks are not enough

Prove Paris was more than paper promises

Prove Paris was more than paper promises