Real and fictional specimens appear side by side in a project called Die Sammlung (The Collection).Credit: Science Gallery, Trinity College Dublin

FAKE Science Gallery Dublin. Until 3 June 2018.

As fake news continues to be big news, the Science Gallery Dublin nudges visitors to look anew at the value of distortion with its latest show, FAKE. The exhibition “probes our society’s flexibility with fact and fiction”, notes head of programming Ian Brunswick. “We want visitors to consider contexts where fake is not such a bad thing.” After all, phony things that succeed become a substitute: think faux fur or synthetic insulin.

Fakery of data in research is ruinous, but art has a licence to playfully subvert or embellish the real. As literary luminary Oscar Wilde, born around the corner from the gallery, had it: “Lying, the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of art.”

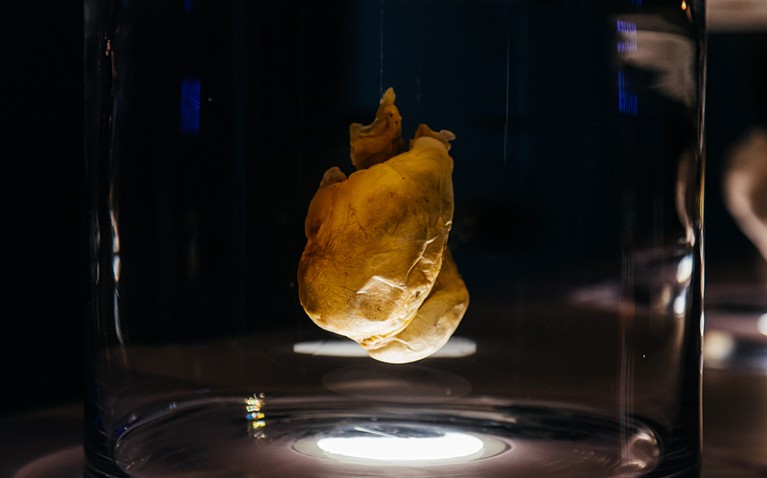

In The Art of Deception, designer Isaac Monté and evolutionary biologist Toby Kiers present ghost hearts: six animal hearts stripped of their cells to leave behind sterile protein scaffolds. Repopulating such frameworks with human cells could one day help to save lives, enabling a suboptimal organ to be replaced. They offer a blank slate for ingenious engineering. “This is both its power and its danger,” says Kiers. One of the hearts has been dipped in hot wax, one recast with foam, one dried like jerky in an airflow cabinet. That enhanced alienness reminds us that we must deceive our bodies into accepting organs from other species.

Animal hearts stripped to their protein scaffolds by designer Isaac Monte and evolutionary biologist Toby Kiers. Credit: Science Gallery, Trinity College Dublin

Meanwhile, artist Heather Beardsley playfully contrasts display conventions in museums in Die Sammlung (The Collection), a pleasing menagerie of real and fictional specimens in antique jars. I picked out a salamander, coral and spider crab, but with these were weird creatures of dubious phylogeny. Close inspection is needed to separate the zoological shams from specimens on loan from the National University of Ireland Galway.

Several exhibits centre on food. Visitors can sample titbits in FAUX Foodmongers, from krab sticks to vegan cheese. Our notions of authenticity and naturalness are probed by artist Crystal Bennes in ≠ C8H8O3, a chance to sample four vanilla-flavoured tablets: natural vanilla and three vanillins, synthesized from a petrochemical product, a wood by-product and fermented yeast. Only 1% of vanilla flavour in foods is derived from vanilla pods, yet supply still can’t satisfy demand. Recycled spruce wood may be sustainable, but the pod wins on taste.

Patricia Pisanelli’s Stretching Cheese, hanging downstairs, is a collage of slices of the stuff, reminding us that products with a cheese content of just 51% can be sold as cheese. Devon Ward and Oron Catts’s Vapour Meats is a plastic see-through head mask through which meat flavours can be inhaled. A motion sensor triggers a nozzle that sprays a chemical vapour into the mask. I wanted to test its meaty bona fides, but university vaping regulations quashed the idea: I’m left wondering whether the odours are fake, or deliver the fatty umami-drenched whiff of the real thing.

Cuttlefish change colour and texture to match their camouflage to reproductions of iconic art in a work by artist Ryuta Nakajima.Credit: Science Gallery, Trinity College Dublin

Other works explore the deception rife in the animal world. Cuttlefish, for example, rapidly change colour and texture in response to their environment — camouflage that underlies Cuttle 61. Artist Ryuta Nakajima decorated aquaria with reproductions of iconic visual art. His photos show how the creatures responded — for instance, turning uniform grey with eye spots to blend with Pablo Picasso’s Ma Jolie. Ecologists can deploy innovative deception for their own ends. In a glass box sits Faux Frog, artist Barrett Klein’s collection of artificial amphibians. These were used in field studies of signalling and mate selection by female túngara frogs in Panama.

A fake túngara frogs created for field studies by artist Barrett Klein and biologists Ryan Taylor and Michael Ryan.Credit: Barrett Klein, Joey Stein and Ryan Taylor.

We, too, can be gulled — in some realms more readily than in others. People can spot fake food, flowers or fruit within 40 milliseconds, notes curator and psychologist Fiona Newell. But our antennae for faked photos might be less acute. A sample from a fake-news exhibition launched last year at the UK National Science and Media Museum in Bradford dates back as far as 1911. I was particularly struck by a newspaper image of two child victims of a crime, set against a fake seaside background. (The paper modified the image — perhaps to ramp up the emotional impact by showing the children in a moment of childhood bliss.)

The ease of hoaxing on social media is clear from Synthesizing Obama. A realistic video shows former US president Barack Obama speaking, but lip-synced to a speech he never made. Realistic faked video and audio develops apace, notes Brunswick; machine-learning techniques have also been harnessed to make short fake videos.

FAKE’s aim is not to frighten people into thinking they are drowning in duplicity, but to probe why we value authenticity. Says Brunswick: “We can’t let the fake-news scandal dominate our entire cultural, scientific and artistic discussion.” Instead, this show explores how questionable truthfulness, deception and ingenious subterfuge tease us. “If people come away with more questions than answers, about fact and fiction and the fuzzy in between,” concludes Brunswick, “we’ve done our job.”

Predatory journals recruit fake editor

Predatory journals recruit fake editor

The second creation

The second creation

Health agency reveals scourge of fake drugs in developing world

Health agency reveals scourge of fake drugs in developing world

In retrospect: Brave New World

In retrospect: Brave New World