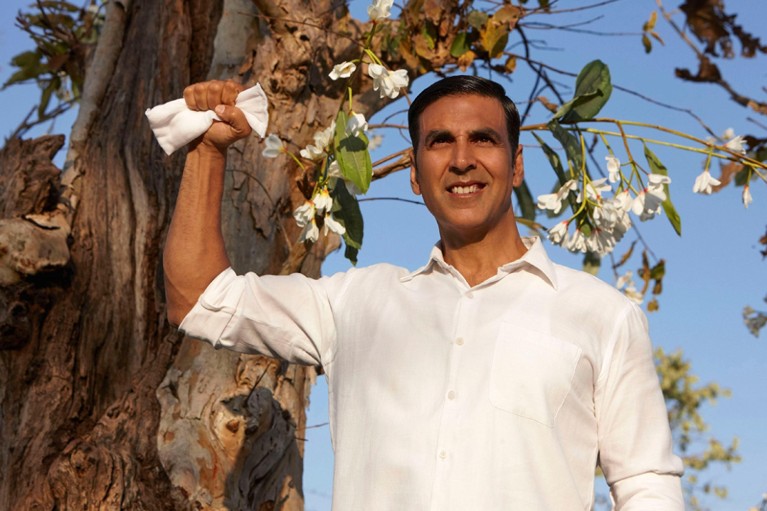

Akshay Kumar plays the lead in Pad Man, a fictionalized biopic of sanitary-pad innovator Arunachalam Muruganantham.Credit: Collection Christophel/Alamy

Pad Man Director: R. Balki Columbia/Hope: 2018.

Frugal innovation is a new norm in India, emerging sporadically in pockets of brilliance — from rural hamlets to technology labs. It has even spawned a word in Hindi: jugaad.

Thanks to jugaad, bioengineer Manu Prakash is flooding rural schools in India with his US$1 ‘foldscope’, an origami-inspired microscope teaching science to tens of thousands of children. It is also in this spirit that, in 2000, school dropout Arunachalam Muruganantham created a do-it-yourself unit in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, to manufacture the world’s cheapest sanitary pads. Now, Muruganantham’s story hits the big screen in Pad Man, billed as the first feature-length film on menstrual hygiene.

‘Period poverty’ is a health issue affecting women in countries across the globe. In Britain, 1 in 10 girls and women aged 14–21 cannot afford sanitary products, according to London-based charity Plan International UK. In India, according to a 2015–16 government health survey, just 58% of women aged 15–24 can afford to use a hygienic method of menstrual protection: 78% in urban areas and 48% in rural ones. And the average varies wildly between states — from 91% in Tamil Nadu to just 31% in Bihar. The rest resort to rags, leaves and even ash. This can result in serious health risks, such as toxic shock syndrome, and lead to absence from school or work.

Pad Man attempts to open up this taboo topic for much-needed discussion through narrative sparked by melodrama and music. Like Shree Narayan Singh’s 2017 film Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, centred around the problem of open defecation, it has captured the imagination of a nation grappling with a massive burden of women’s health issues.

Directed by R. Balki, Pad Man has a starry cast. Muruganantham (renamed Lakshmikant) is played by renowned Bollywood action-hero-turned-character-actor Akshay Kumar; the powerful theatre actor Radhika Apte plays his wife, Shanthi (called Gayatri). There is even a jingoistic cameo from superstar Amitabh Bachchan, who, playing himself, declaims: “India should not be seen as a country of one billion people. India should be seen as a country of one billion minds.”

Muruganantham’s is the inspiring story of an unconventional and tenderhearted man. In the early 1990s, he was an assistant in a hardware workshop. His wife’s use of rags during menstruation concerned him, so he experimented with materials — first cotton, then cellulose fibre — to make a pad that wouldn’t leak, in a process of reverse engineering. At first, when it came to testing his prototypes, “the only available victim was my wife”, Muruganantham said in a 2012 TED talk. In Pad Man, we see Lakshmikant perfecting the scientific steps of pulverizing cellulose fibres, compressing them, sealing the pad with non-woven fabric and sanitizing the whole with ultraviolet light. And it was all accomplished using four ingenious, makeshift machines that cost peanuts, compared to the giant assembly lines used by multinational companies.

At the cost of being ostracized for openly tackling a hidden issue, he worked doggedly on the pad’s design. The biggest challenge was finding volunteers to test it. “Everyone thought I had gone mad,” he says. He finally realized that he could turn guinea pig himself. He wore a pad, and used a deflated football filled with goat’s blood and fitted with a tube. It took him six years to isolate cellulose as the core adsorbing medium. That roller-coaster journey won him a national innovation prize, a spot on TIME magazine’s ‘100 most influential people’ list in 2014, and one of India’s highest civilian awards, the Padma Shri, in 2016.

Pad Man makes Muruganantham’s unusual journey relatable, although it often descends a little into preachiness. It falters, too, with a laboured first half, in which the risk to women’s health is not clearly delineated, and the stigma associated with the subject of menstruation is signalled by bursts of “Sharam!” (shame) from the female actors. Endorsing Bollywood’s unapologetic love affair with song and dance, the demure Gayatri suddenly breaks into an exaggerated, hip-swaying number to celebrate the puberty of a girl next door.

The rest of the film brings in the usual elements of a potboiler — a love angle, the rise and rise of the protagonist and Gayatri’s forgive-and-feel-proud reconciliation. Bachchan delivers the applause-inducing line: “America has Superman, Spiderman and Batman. India has Pad Man!”

Over the past decade, Muruganantham has travelled across villages in India — first selling his sanitary pads, and then setting up self-sustaining pad-making units in collaboration with women’s self-help groups and cooperatives. He has spawned close to 2,500 such centres, in India and a dozen other developing countries. His pads retail at a fraction of the cost of those from multinational brands.

Although Pad Man captures the essence of grass-roots innovation and benefits from true-to-life portrayals by a brilliant set of actors, the instructive overtone mars the narrative. If it wants to reach other countries affected by period poverty, the song-and-dance might be a dampener. The film is also currently an urban sensation. Reaching its target audience in India’s rural hinterland might be difficult, given the taboo — unless Balki and team have a plan for that.

Meanwhile, a social movement is now associated with the film. Muruganantham has mentored a biologist, Maya Vishwakarma, who came home to rural Madhya Pradesh from California four years ago to spread menstrual-hygiene awareness. Vishwakarma has now received backing to distribute free pads to tribal women. Her mission has earned her the sobriquet Pad Woman. The buzz created by Pad Man might help her small non-profit organization to get international donors and become a national movement.

Nature Outlook: Women's health

Nature Outlook: Women's health

The bottom line

The bottom line