Traditional farmhouses are overlooked by an illuminated bridge in Chongqing, China.Credit: Mark Horn/Getty

When Raymond C. Stevens moved to Shanghai in 2011 for a nine-month sabbatical, he was curious. After spending his career in the United States, establishing a laboratory at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and three biotechnology start-ups, the chemist sensed that China might be the next research frontier.

“I wanted to get a refreshing perspective,” says Stevens, now the director of the iHuman Institute at ShanghaiTech University and founder of another, China-based start-up. “I was curious about science in China, what drug discovery was like, and wanted my three children to experience life in China since I felt it might open opportunities for them later in life.” Although Stevens enjoyed life in China, he and his family wanted to be closer to their relatives in the United States, and, six years later, decided to move back. Stevens continues to spend almost half his year working in Shanghai.

Whether you’re a tenured professor or just starting out as a postdoctoral researcher, it’s hard to miss China’s vast science and technology ambitions. During the opening of the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party last October, President Xi Jinping affirmed the need for China to become “a nation of innovators”. In 2019, China is predicted to surpass the United States as the world’s largest investor in research and development (R&D).

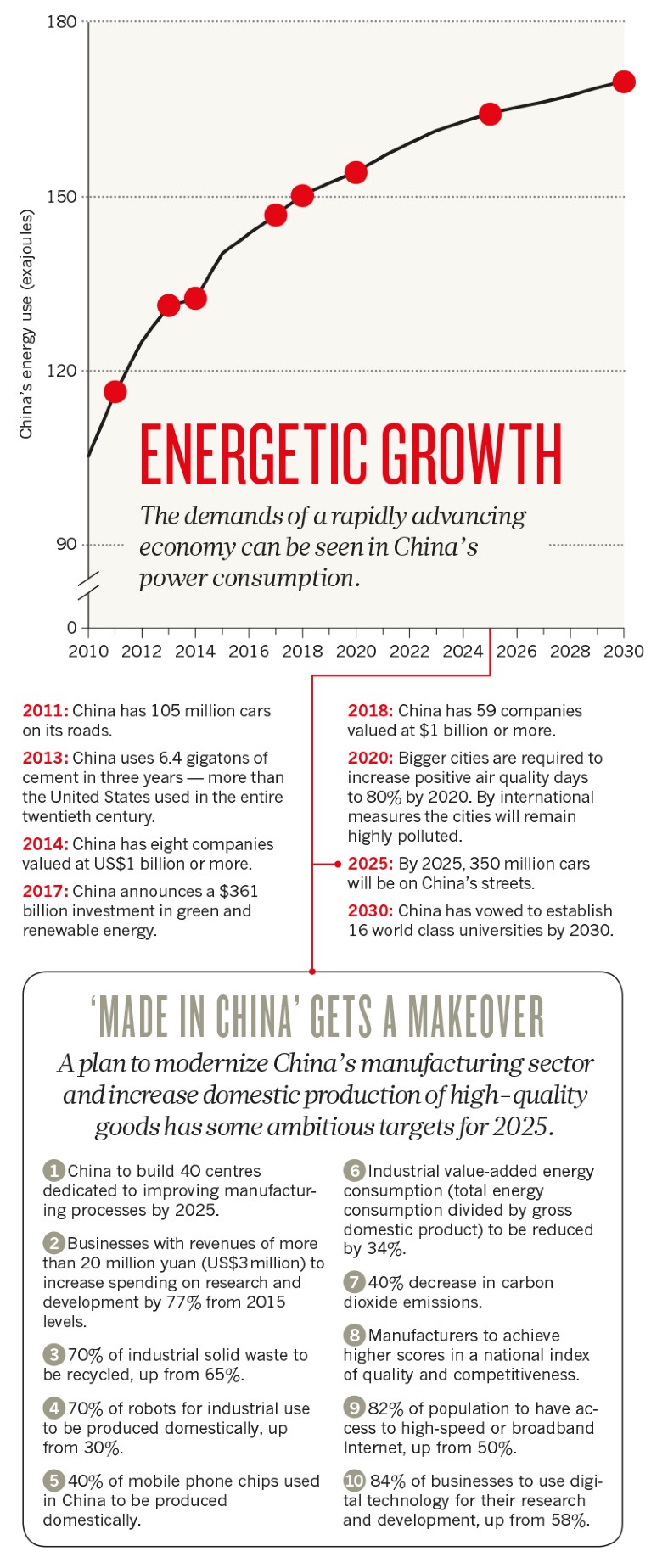

Over the past decade, China’s leaders have focused on transforming a nation of farmers and factory workers into a highly skilled workforce. In 2006, China announced a 15-year science and technology plan, which set targets for everything from spending levels to the number of patents that must be filed. The aim was to transform China from a low-cost manufacturing hub into an economy driven by domestic innovation. In 2016, China’s leaders went further, stating that by 2050 the country will be a world-leading scientific powerhouse (see ‘Energetic growth’).

Source: US Energy Information Administration

“Science is culturally well appreciated in China, perhaps comparable to sports in the United States,” says Stevens. “Students are filled with incredibly strong desire and sense of curiosity about science. For me this is the most exciting reason to be working in China today.”

China’s investment in R&D is crucial to the country’s stability. As the country’s economy matures, its growth rate is slowing. The economy is expected to grow no more than 6.4% in 2018 — a far cry from the rapid gains of 10% per year in recent decades. Coupled with this economic deceleration are the twin pressures of growing labour costs and a shrinking workforce. Owing to the country’s historically strict family-planning policies, by 2050, more than one-quarter of China’s population will be over 65, and only around one-half will be of working age.

Investment for the future

Well aware of the need for change, the country’s leaders are putting money behind new businesses. Start-up investment funds run by local authorities across the country totalled US$332.6 billion in 2015, and the plethora of business incubators across the country helped to produce 223,000 companies by the end of 2016. The consultancy firm McKinsey says that innovation could contribute as much as 50% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 2025. By 2020, China wants to have more than 10,000 domestic incubators, accelerators and other start-up havens, and 100 abroad. From designing new semiconductors and chemical products to re-imagining the role of artificial intelligence in everyday life, China will be relying on its growing pool of talented scientists and entrepreneurs to come up with ideas, bring them to life and take them to market.

State-of-the-art research facilities are being built across the country, and scientists say research funding is prolific. “I feel that in North America, the pace is very slow. In China, there is all the support and all the funding you need, so the pace is very fast,” says Zhongqi Shao, who moved to China to work as vice president of vaccine research at the vaccine developer CanSino Biologics in Tianjin, after having worked for pharmaceutical companies in Canada for decades.

The strong support for science and technology is also a means for China to address pressing social problems; 43 million people are living below the country’s poverty line, according to government figures. Farmers make vital income by selling everything from trinkets to furniture and dried fruit on China’s giant e-commerce website Taobao. On the streets of the country’s cities, young entrepreneurs have transformed the commute of millions of Chinese with the introduction of bike-sharing apps. They hope to reduce air pollution as well as traffic jams.

Technology is also tackling problems arising from China’s rapidly ageing society. Companies are counting on artificial intelligence to replace millions of unfilled low-skilled and labour-intensive jobs. Like everyone else, China’s elderly are embracing technology: robots are not only being deployed to assist in medical care, they’re also seen by residents in care homes as a means to ease their loneliness. They encourage the little machines to dance and play karaoke songs.

Planning ahead

China has been run by the Communist Party for almost 70 years, and the resulting stability has enabled politicians to set and execute long-term goals. The nation’s science and technology priorities are plain to see in the latest five-year development plan — the thirteenth since 1953. The government’s priority is to foster innovation by increasing the share of GDP spent on R&D to 2.5% by 2020, up from 2.1% in 2015, which would bring it on par with the average spend by countries in East Asia and the Pacific region. If China reaches this target, it will spend an estimated $1.2 trillion on R&D over the course of the plan.

China is already the world’s second-largest investor in technological innovation, after the United States, and spent more than $200 billion on R&D in 2015. Since the turn of the century, China has increased tertiary education spending and created state-of-the-art research facilities — investments in human capital seen as vital to drive innovation. Under the new plan, policymakers hope to increase the number of staff directly working in R&D — from bench engineers and scientists to their managers — to 60 per 10,000 employees, up from 48.5 in 2015. The plan also suggests that 10% of China’s population should have a scientific degree by 2020, up from 6.2% in 2015. But employers say that Chinese graduates still lack the soft skills necessary to generate new ideas, such as analytical thinking and an ability to communicate effectively.

Slowly, however, past investments are paying off, says Cong Cao, a professor of Chinese studies at the University of Nottingham Ningbo in China. “The investment in human capital has been significant, with Chinese universities having turned out more and increasingly high-quality graduates,” Cao says.

To bridge the gap between research and commercial use, the government is investing heavily, and has created a national small- and medium-sized enterprises development fund, with $9.4 billion slated for the development of private start-ups. China has also invested in several online services in the travel and tourism industry. Innovation parks and centres are sprouting up even in smaller cities; some offer free rent to individuals for up to five years. University graduates are being offered financial incentives by city governments, such as free rent and tax cuts, to take a leap of faith and start a business.

Although China still lags behind high-income economies when it comes to certain areas of innovation, such as designing car engines or creating new drugs, the policies seem to have had tangible results. According to the report The Global Innovation Index 2017, which measures dozens of indicators ranging from patent filings to education spending, China leapfrogged Estonia and Australia to go from 25th to 22nd in 2017.

Perhaps more tellingly, state media reported that in 2015, double the number of students intended to start their own businesses compared with the previous year. Whatever they start will have to be flexible — China is changing fast.

How to find a job in China

How to find a job in China

The ups and downs of moving to China

The ups and downs of moving to China