Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are a group of chronic progressive disorders characterized by neuronal loss. Necroptosis, a recently discovered form of programmed cell death, is a cell death mechanism that has necrosis-like morphological characteristics. Necroptosis activation relies on the receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homology interaction motif (RHIM). A variety of RHIM-containing proteins transduce necroptotic signals from the cell trigger to the cell death mediators RIP3 and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL). RIP1 plays a particularly important and complex role in necroptotic cell death regulation ranging from cell death activation to inhibition, and these functions are often cell type and context dependent. Increasing evidence suggests that necroptosis plays an important role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, small molecules such as necrostatin-1 are thought inhibit necroptotic signaling pathway. Understanding the precise mechanisms underlying necroptosis and its interactions with other cell death pathways in neurodegenerative diseases could provide significant therapeutic insights. The present review is aimed at summarizing the molecular mechanisms of necroptosis and highlighting the emerging evidence on necroptosis as a major driver of neuron cell death in neurodegenerative diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

Necroptosis is closely associated with the pathogenesis of different kinds of neurodegenerative disease.

-

Necroptosis can be widely stimulated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF), other members of the TNF death ligand family (Fas and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)), interferons, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) signaling and viral infection via the DNA sensor DNAdependent activator of interferon regulatory factor (DAI). Various upstream signaling pathways share the common terminal mechanism executed by mixed lineage kinase domain-like proteins.

-

Blocking necroptotic pathways with synthetic inhibitors or genetic manipulation mitigates neurodegenerative disease in vitro and in vivo, which suggests a promising therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative disease.

Open Questions

-

How to monitor necroptosis in the diagnosis and prognosis of neurodegenerative disease?

-

What are the relative contributions of necroptosis and other forms of programmed cell death to neurodegenerative disease?

-

Would synthetic inhibitors be the most effective against necroptosis-associated neurodegenerative disease in clinical settings?

Historically, two forms of cell death have been recognized: necrosis and apoptosis. They play essential roles in development, homeostasis, and pathogenesis.1 Traditionally, necrosis has been considered as an accidental death resulting from an over-whelming cytotoxic insult, and requires no specific molecular events. In contrast, apoptosis, which is characterized by apoptotic body formation, nuclear shrinkage and fragmentation, and membrane blebbing, had been researched as the main form of programmed cell death.2 However, increasing studies have described a genetically programmed and regulated form of necrosis, termed necroptosis.3, 4 Necroptosis can be triggered by the ligands of the death receptor family and extracellular and intracellular stimuli that induce their expression. The receptor-interacting kinase 3 (RIP3)5, 6, 7 and its substrate, the pseudokinase mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL)8, 9 have been discovered to be core components of necroptotic signaling pathway. Morphologically, necroptosis resembles cellular necrosis, which is distinguished from apoptosis by the presence of clusters of dying cells, an early loss of plasma membrane integrity, cell and organelle swelling, granular cytoplasm, chromatin fragmentation, and cellular lysis.10 In contrast to apoptosis, the cellular contents of necroptotic cells passively enter the extracellular matrix through the disrupted cell membrane.10

Necroptosis is involved in many pathological processes, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury in the heart,11 brain,4 and in injury-induced inflammatory diseases.12 Necroptosis reportedly plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases (Figure 1). Researchers have focused their attention on necroptosis due to its potential as a target for intervention in neurodegenerative diseases. In this review, we will discuss the molecular mechanisms of necroptosis and examine the growing evidence favoring a role for necroptosis in the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases. We will also describe and comment on the effects of necroptosis in disease pathogenesis that may encourage research that will help in seeking therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

Timeline for momentous events in the studies of necroptosis and its role in neurodegenerative diseases. Blue boxes represent the major findings in the discovery of necroptosis signaling pathway; yellow boxes highlight the research breakthroughs concerning the role of necroptosis in neurodegenerative disease

Activation of Necroptosis and Formation of Necrosome

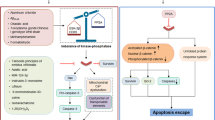

Currently, one of the best studied form of necroptotic cell death is initiated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF), but necroptosis can also be induced by other members of the TNF death ligand family (Fas and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)), interferons (IFNs), Toll-like receptors (TLRs) signaling and viral infection via the DNA sensor DNAdependent activator of interferon regulatory factor (DAI).3 Here we take TNF as an instance to elaborate on the signal pathway of necroptosis. TNF activate TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) through the pre-ligand assembly domain in the extracellular portion of TNFR1 and then triggers the trimerization of TNFR1.13 This process, then initiates the assembly of a transient molecular complex named complex I, which consists of TNFR1-associated death domain protein (TRADD), TRAF2, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1/2 (cIAP1/2) and RIP114,15 (Figure 2). RIP1 was originally identified as a protein which interacted with TNFR1 signaling complex. Recent studies have revealed that in addition to being a regulator of necroptosis, RIP1 also participates in regulating inflammation and apotosis.16, 17, 18

Necroptotic pathways. After TNF stimulation, TNFR1 recruits TRADD and RIP1 to complex I via their respective death domains. TRADD recruits cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAPs), which ubiquitinate components of complex I. Deficient complex I activity, such as occurs with the deubiquitination of RIP1 by cylindromatosis (CYLD), can lead to the formation of the necrosome, which consist of FADD, procaspase-8, RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL. RIP1 interacts with FADD though death domain. Subsequently, procaspase-8, cFLIPL and cFLIPS are recruited to death receptor-bound FADD. Procaspase-8 homodimerization generate processed active caspase-8, which activates effector caspase cascade and induces apoptosis. Procaspase-8-cFLIPL heterodimer does not process caspase-8 but cleaves RIP1, which leading to cellular survival. However, procaspase-8-cFLIPS heterodimer fails to cleave RIP1, which allows the assembly of necrosome and the execution of necroptosis. In the necrosome, MLKL are phosphorylated and translocate to the plasma membrane, which leads to influx of Ca2+ or Na+ ions and direct pore formation with the release of cell damage-associated molecular patterns (cDAMPs) such as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), interleukin (IL)-33, IL-1α, and ATP. zVAD, a pan-caspase inhibitors, inhibits caspases cascade and apoptosis. Nec-1 inhibits RIP1 kinase activity and necroptosis. NSA blocks necroptosis by preventing the membrane translocation of MLKL. Boxes around the cell model diagram represent the major pathogenesis of the neurodegenerative diseases in this review except ALS, of which the etiology remains unknown

In complex I, RIP1 is rapidly ubiquitinated by E3 ligases such as cIAP1.3 Ubiquitination of RIP1 plays an important role in regulating its kinase activity. Blocking RIP1 ubiquitination by antagonizing cIAP1/2 increases the sensitivity of cells to TNF-induced necroptosis.19, 20, 21 Cylindromatosis (CYLD), a K63-specific deubiquitinating enzyme,22 mediates the deubiquitination of RIP1 to facilitate the formation of complex IIb, which also termed necrosome,23, 24 which consists of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL.6, 7 FADD and procaspase-8 can also be detected in necrosome25 (Figure 2). Recently, c-FLIP (caspase 8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator), a catalytically inactive homolog of caspase-8, was reported to participate in the regulation of necroptosis.26 When a heterodimer is formed with c-FLIP long (c-FLIPL), caspase-8 maintains sufficient proteolytic activity to prevent the association of RIP1, RIP3 and FADD, thus inhibiting necroptosis.19 However, when caspase-8 is combined with c-FLIP short (c-FLIPS), it has no proteolytic activity, which allows the assembly of RIP1 and RIP3 and thus promotes necroptosis19 (Figure 2). In the absence of CYLD, necrosome formation is significantly inhibited in TNF-induced programmed necrosis.3 The activation of RIP1 leads to the recruitment of RIP3, a critical downstream mediator of necroptosis. RIP1 interacts with RIP3 through the RHIM motif to form an amyloid-like signaling complex in necroptotic cells.27 A critical consequence of RIP1 interaction with RIP3 is the phosphorylation of the latter.5, 6, 7 Enforced dimerization of RIP3 can also directly lead to its autophosphorylation.28 Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1),29 Nec-1s30 and other small molecules31, 32 were identified as small-molecule inhibitors of necroptotic signaling pathway, and they have been widely used to study the molecular mechanisms of necroptosis (Table 1).

Execution of necroptosis

MLKL, which is detected in necrosome, is the most downstream effector of necroptosis identified so far.9, 33 MLKL contains an N-terminus coiled-coil domain region and a C-terminal kinase-like domain which binds the kinase domain of RIP3.9 The drug necrosulfonamide (NSA) was found to target MLKL and inhibit necroptosis.9, 32 NSA prevent the membrane translocation of MLKL, but has no effect on its phosphorylation or oligomerization.9, 34 The binding of RIP3 to MLKL is dependent on RIP3 kinase activity and the phosphorylation of RIP3.9 In addition, MLKL is phosphorylated by RIP3.9 Structural studies of MLKL allowed the identification of functionally important residues in MLKL. Mutations in ATP binding region of MLKL protein result in a constitutively active MLKL.35 A similar effect was observed for a phospho-mimic of one of the sites targeted by RIP3.35 These mutants can cause necroptosis in unstimulated cells, indicating the importance of MLKL modification in the necroptosis pathway downstream of RIP3 (ref. 35) MLKL deficient cells can undergo apoptosis but they are resistant to TNF-induced necroptotic cell death, as well as to LPS, oxLDL and partially cyclohexamide necroptosis, indicating that MLKL is a common downstream effector of different necroptotic death pathways.33 Recent studies reported that besides participate in necroptosis active MLKL also triggers the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome in a cell-intrinsic manner, which is required for the activity of IL-1β released during necroptosis.36, 37

Recently, several researches have explored the role of MLKL in necroptosis.8, 9 MLKL oligomerizes through its N-terminal four-helix bundle, which triggers its translocation to the plasma membrane.34 Oligomerization of MLKL is induced by RIP3 mediated phosphorylation at the kinase-like domain of MLKL.9 The mechanisms of MLKL underlying necroptosis are not completely clear. One study reported that MLKL in the plasma membrane binds to the transient receptor potential melastatin-related 7 (TRMP7) ion channel, which leads to the influx of Ca2+ ions and induced cell death eventually38 (Figure 2). Another study stated that MLKL complex acts either by itself or with other proteins to increase the sodium influx by regulating the Na+ channels that triggers Na+ entrance, which increases osmotic pressure of cytoplasm, eventually leading to membrane rupture.39 Meanwhile, necroptosis causes severe inflammation through the release of cell damage-associated molecular patterns (cDAMPs),40 including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), interleukin (IL)-33, IL-1α, and ATP41(Figure 2). In addition to the mechanism mentioned above, there are several studies showed that MLKL may be directly responsible for pore formation and membrane disruption.34, 42

Necroptosis in Neurodegenerative Disease

Increasing evidence indicates that necroptosis may contribute to neuron death in several neurodegenerative disorders (Table 2). The signaling cascades leading to the organization of the necrosome can be inhibited by small molecules (Table 1). Treatment with Nec-1 was reported to be neuroprotective in cerebral ischemia4 and brain trauma.43 Furthermore, Nec-1 has been shown to be efficacious to target the necroptosis pathway in animal models of Huntington disease (HD)44 and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).45 In this review, we investigate the role of necroptosis in neurodegenerative disorders and evaluate the potential of inhibiting necroptotic signaling pathway as a therapy for neurodegenerative disorders.

Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD), which is the most common neurodegenerative disease, is characterized by the accumulation of misfolded β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) plaques in the brain and neurofibrillary tangles composed of phosphorylated tau protein.46 However, the exact cause for AD is still not well understood. Recently, several studies have suggested that necroptosis may participate in AD.47, 48

Cells and animals treated with aluminum (Al) exhibite a significantly reductions in neuronal viability, neurofibrillary tangle formation, and AD symptoms, which might serve as a model of AD.49, 50, 51, 52, 53 Nec-1 might protect against Al-induced cell death by reducing the phosphorylation of RIP1. Moreover, Nec-1 improved the viability of Al-treated cell to a greater extent than zVAD-fmk and 3-methyladenine, which inhibit apoptosis and autophagy respectively.48 A study reported a similar conclusion: necroptosis is involved in Al-induced neuroblastoma cell death.50 Al-treated mice also showed a notable increase of neuron viability after they were treated with Nec-1, the behavior of animal were obviously better than controls, levels of RIP1 and AD-related proteins such as Aβ and Tau were significantly and dose-dependently decreased in the brains of mice model.48 These results suggest that necroptosis represents a potentially important pathway in AD pathogenesis. Nec-1 might slow the progression of the cognitive deficits associated with AD.

Consistently, Yang et al. examined amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice and reported that Nec-1 regulated multiple pathological culprits that are important in AD.47 Moreover, bimolecular binding between RIP kinase and Aβ was observed.47 Interaction between these two proteins in the extracellular and luminal regions might be involved in Aβ-related cell death pathology in AD and therefore might serve as a potential drug target for the disease.47 Further studies are needed to better understand how Nec-1 can selectively target and regulate Aβ and tau aggregation and investigate whether the therapeutic effects of Nec-1 translate into an intervention that might be potentially useful for AD.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder with no known cure, estimated to affect 4 million people worldwide. It is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in striatum and substantia nigra and accumulation of modified α-synuclein in the degenerating neurons termed as Lewy bodies.54 However, the specific molecular events that occur during cell death in PD remains unclear. Recently, evidence has indicated that autophagy, which is downstream of necroptosis, is involved in dopaminergic cell death in PD.55, 56, 57

Wu et al. reported that Nec-1 could block necroptosis and give protection to dopaminergic neurons.58 They used 6-Hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced PC12 cells as a PD model59 to explore the role of necroptosis in PD by examining autophagic activation. Mitochondrial disability in PD cell model induced overactive autophagy, increased cathepsin B expression, and diminished Bcl-2 expression.58 Within a concentration of 5-30 μM, Nec-1 increased the viability of the PC12 cells, stabilized the mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibited excessive autophagy, reduced the expression of cathepsin B and LC3-II, and increased Bcl-2 expression.58 However, when the concentration of Nec-1 was increased to 60 and 90 μM, PC12 cells viability decreased, indicating dual effects of Nec-1, protection at lower concentrations versus toxicity at higher concentrations.58 These results were consistent with a point of discussion made by Smith and Yellon.60

These findings suggested that Nec-1 was neuroprotective against dopaminergic neuronal injury. The mitochondrial function-protective effects suggested that Nec-1 might have an antiapoptotic effect by stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane.58 The reversed effects on the levels of expression of LC3-II and cathepsin B in 6-OHDA-treated PC12 cells suggested that Nec-1 prevents autophagic cell death and downstream necroptotic signaling in the PC12 cells.58 However, based on these limited findings, it is still unknown whether Nec-1 has a protective effect in PD animal models. In vivo testing of Nec-1 will undoubtedly be the key to understanding its neuroprotective efficacy in PD.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

ALS is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord, cortex and brain stem, leading to muscular atrophy and paralysis.61 The cell death mechanism in ALS has long been unclear. Recently, researchers have found that necroptosis is involved in neuron death in ALS.45, 62 In these studies, a humanized model was created by co-culturing human embryonic stem-cell-derived motor neurons (hES-MNs) with astrocytes collected from the motor cortex and spinal cord of ALS patients after death.62 The ALS astrocyte hES-MNs co-culture exhibited the ALS features of non-cell autonomous astrocyte-induced toxicity and was specific to motor neurons.62 In the co-cultures, silencing of neither SOD1 nor TDP-43 did not rescue motor neuron viability,62 providing evidence that neither misfolded SOD1 nor TDP-43 are necessary cytotoxic factors in sALS pathogenesis, which is contradict the results of other group.63

Researchers performed different cell death assays in the co-culture system. The sALS astrocyte hES-MNs co-culture showed significant DNA fragmentation, caspase-3 activation and decreased plasma membrane integrity, which showing evidence for both apoptosis and un-programmed/programmed necrosis.62 To further investigate this issue, inhibitors were used to block different cell death pathways. Unexpectedly, zVAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor, effectively eliminated caspase-3 activation, had no effect on the number of surviving motor neurons, indicating a caspase-independent cell death mechanism.62 These results conflict with a previous study that caspase inhibition prevents motor neuron cell death in mSOD1 mouse models,64 perhaps indicating that the cell death mechanisms in mSOD1 and sALS may be distinct. Further studies are needed to adequately address such issues. As described above, caspase-independent programmed cell death is strong evidence to suggest programmed necrosis and perhaps necroptosis. Treatment with Nec-1 further prevented motor neuron cell death to control levels.62 These results were confirmed by RIP1 knockdown in vitro. Treatment with NSA resulted in similar levels of motor neuron viability as controls, which suggested that inhibiting MLKL prevented motor neurons from undergoing cell death.62 Thus, these results provide preliminary evidence that the necroptosis pathway may has a major role in driving motor neuron death in sALS. However, the evidence was generated in vitro.

Mutations in the optineurin (OPTN) gene have been implicated in both fALS and sALS pathogenesis.65, 66, 67 Ito et al. have shown that OPTN−/− mice have a decreased number of motor axons, abnormal myelination in the ventrolateral spinal cord, and a mild behavior phonetype.45 However, the total number and the bodies of neurons cell remained unaffected, researcheres considered that OPTN deficiency sensitizes cells to cell death in the spinal cord white matter of OPTN−/− mice.45 A subsequent study found that RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL were upregulated in the spinal cords of OPTN−/− mice and in SOD1 mice model,45 and increased levels of RIP3, along with activated RIP1 and MLKL were found in spinal cords of post-mortem ALS patients,45 which suggests that necroptosis may participate in the pathological process of ALS.45 Lineage-specific deletion of OPTN showed that it is oligodendrocytes and microglia that reproduced motor axon pathology in OPYN knockout mice.45 Researchers noted that OPTN–/– oligodendrocytes were sensitized to die by TNFα-induced necroptosis but were protected by Nec-1s and in OPTN–/–; RIP1D138N/D138N and OPTN–/–;RIP3–/– double mutants.18, 45, 68 Thus, OPTN deficiency can promote necroptosis of oligodendrocytes. Moreover, the OPTN-knockout microglia exhibited a proinflammatory state and low expression levels of MLKL and increased levels of phosphorylated RIP1,45 which suggests that RIP1 activation in microglia may promotes inflammatory signaling not necroptosis.

Consistent with this hypothesis, an increased production of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukins IL-1a, IL-1b, IL-2, and IL-12; interferon-g (IFN-g); and TNFα in the spinal cords of OPTN−/− mice were observed.45 However, the expression of these proinflammatory cytokines were markedly reduced in the OPTN−/−;RIP1D138N/D138N mice. The elevated TNFα in OPTN−/− microglia can be inhibited by Nec-1s.45 In this study, Nec-1s was used as the RIP1 inhibitor instead of Nec-1. Another study examined three Nec-1 analogs: Nec-1, Nec-1 inactive (Nec-1i), its inactive variant, and Nec-1s,29, 69 its more stable variant.30 Both Nec-1 and Nec-1i inhibited human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO),70 a potent immunomodulatory enzyme, but Nec-1s did not.30 Therefore, Nec-1s appears to be a more specific inhibitor of RIP1 and to lack the IDO-targeting effect. Next, Nec-1i was shown to be less effective compared with Nec-1 and Nec-1s in the inhibition of RIP1 kinase activity in vitro and in vivo.30 Importantly, low doses of Nec-1s did not exhibit cytotoxicity rather than Nec-1 or Nec-1i.30 Thus, it is suggests that the use of Nec-1s may provide a perfect alternative to the inhibition of RIP1. More studies are needed to determine whether OPTN deficiency results in inflammation. These results indicate that OPTN deficiency leads to motor axon defects by driving necroptosis in oligodendrocytes and/or a proinflammatory phenotype in microglia.45 Taken together, results above suggest a connection between RIP1-regulated necroptosis and inflammation. By regulating both inflammation and necroptosis, RIP1 may be a common mediator of axonal pathology in ALS, blocking RIP1 may be an effective intervention for the treatment of ALS.

Huntington’s Disease

HD is characterized clinically by movement abnormalities, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive deficits. Mutant Huntingtin (Htt) with expanded polyQ (glutamine) repeats causes the dysfunction and death of neurons, particularly striatal neurons.71 The mechanism underlying the striatal cell death remains elusive and no effective treatments are available for this fatal disease.

ST14A is an immortalized striatal cell line with medium spiny neurons (MSNs) characteristics72 and ST14A 8plx line stably expressing mutant Htt fragment was established as a cell model of HD.73, 74 Inhibition of death receptor signaling by zVAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor in apoptosis, leads to RIP1 kinase activation and cell death in ST14A and ST14A 8plx line cells, which can be almost completely rescued by Nec-1 (ref. 44) Unlike apoptosis, dying striatal cells showed atrophy and shrinkage of the cell body and had no caspase-3-specific cleavage. Nec-5, another RIP1 inhibitor,29 can not inhibit zVAD-fmk induced striatal cell death, indicates that there may be an alternative intrinsic RIP1 activation pathway in striatal cells.44

Investigator evaluated the Nec-1 in R6/2 transgenic mouse model of HD, which expresses exon 1 of mutant human htt gene.75 Given that Nec-1 can cross the blood-brain barrier easily but has a short half-life, about 1 h,76 Zhu et al. delivered Nec-1 intracerebroventricularly with Alzet osmotic pump to ensure continuous supply of the drug.44 Consequently, the expression of full-length RIP1 protein is increased in R6/2 mice compared with wild-type control.44 Nec-1 treatment helped maintain the motor functions and body weights in the R6/2 mice and significantly delayed disease onset. However, the survival benefit was modest.44 This discrepancy might be due to different mechanisms involved in early and late disease stages. Researches showed that apoptotic characteristics can be detected in late stage of R6/2 mouse and in grade 3 and grade 4 patients’ brain.77 The differentiation between early and late stages of the disease may due to different sensitivity of mutant striatal cells to excitotoxicity.44 According to Zuccato et al., the extensive and early involvement of activated astrocytes in HD pathogenesis might be induced by the necroptotic activation in early disease stage.71 In ST14A cells, Nec-1 treatment increased the cleavage of full-length RIP1, indicating the higher basal caspase-8 activity, which might have a side effect in the late apoptotic stage of the disease in mice.44 As RIP1 protein is also involved in caspase-8 activation in apoptosis, the interplay of apoptosis and necroptosis is even more complicated.78 Hence, concomitant treatment with both apoptosis and necroptosis inhibitors may have better therapy effect on HD. Finally, as Nec-1 helped ameliorates symptoms in R6/2 mouse, it can be considered as a potential treatment of HD patients.

Niemann-Pick Disease

Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal lipid storage disorder with progressive neurodegeneration.79 NPC is classified as type C1 (NPC1) or type C2 (NPC2), which are caused by mutations in the NPC1 or NPC2 genes, respectively. Mutations in the NPC1 gene account for 95% of NPC patients.80 Degeneration of cerebellar Purkinje neurons is a prominent early feature in the disease progression, which leads to clinical symptoms of motor impairments.81 Very little is known about the cellular death mechanisms leading to neuronal loss in NPC1, and thus the potential efficacy of cell death inhibitors remains unexplored. A recent study reported that activation of the necroptotic pathway contributes to neuronal death in NPC182 The expression level of RIP1 and RIP3 are raised with the formation of the necrosome in NPC1 fibroblasts.82 Consist with the results in NPC1-mutant mice and human patients brain tissue, thus strongly suggesting that necroptosis has a pathological role in NPC1.82 Of note, the formation of the necrosomal complex appeared to be more prominent in fibroblast lines from subjects with age adjusted neurological severity scores83 less than or equal to 1.5.82 Indicates that activation of the necroptotic pathway may be correlate with disease severity.

The mechanism by mutant NPC1 influences the disease are not fully understood. It is clear that necroptosis activation occurs during NPC1 progression, with an abundance of RIP1 and RIP3 found in NPC1 fibroblasts and post-mortem brain tissue of NPC patients compared to controls.82 Treatment of NPC1 fibroblasts from NPC1 patient with Nec-1 or suppression of either RIP1 or RIP3 expression can significant suppress cell death.82 Treatment of Npc1−/− mice with Nec-1 resulted in delayed cerebellar Purkinje cell loss, delayed progression of neurological manifestations and significantly prolonged lifespan.82 These results provide a strong link between necroptosis with the molecular mechanism that contributes to neuronal loss in NPC1.

Gaucher’s Disease

Gaucher's disease (GD) is an inherited metabolic disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding glucocerebrosidase and is the most common lysosomal storage disease.84 Impairment of glucocerebrosidase activity leads to accumulation of the sphingolipid glucosylceramide, which results in disease pathology via unknown mechanisms. The neuronopathic forms (types 2 and 3), which comprise 6% of patients with GD, are characterized by neuronal loss, microgliosis, and astrocytosis.85 Little is known about the molecular events leading to neuronal death.

Researchers detected profound levels of cell death in the cerebral cortex of Gbaflox/flox; nestin-Cre mice, and in a conduritol-β-epoxide (CBE) induced mice model of GD.86 However, no signs of apoptosis were observed.87 Similarly, there was no elevation in caspase-9 or caspase-3/7 activity, and no cleavage of caspase-8.87 This suggests that neuronal cell death in nGD is caspase independent and nonapoptotic. Vitner et al. reported that levels of RIP1 and RIP3 were markedly elevated in the brains of symptomatic Gbaflox/flox; nestin-Cre mice. Moreover, they detected elevated levels of c-FLIPs in the brains of symptomatic mice,87 suggesting the presence of a caspase-8-cFLIPs heterodimer, which would explain the lack of caspase-8 activity.88 Importantly, the expression of RIP1 was also elevated in brain of a patient who succumbed to type 2 GD compared to an age-matched control brain.87 These results indicate that necroptosis may play an important role in nGD brains. Moreover, RIP3 was mainly expressed in the nuclei of neurons from Gbaflox/flox; nestin-Cre mice, in contrast to control mice where it was located in the cytoplasm, which implies a possible role for RIP3 in neuronal cell death.87

RIP3-deficient mice treated with CBE were used to explore the role of RIP kinases in GD pathology. RIP1-null mice die early after birth and are unsuitable for research.89 Glucocerebrosidase activity is inhibited in all cell types and organs upon CBE treatment,90, 91 in contrast to the Gbaflox/flox; nestin-Cre mouse model in which glucocerebrosidase deficiency is restricted to cells of neuronal lineage. Levels of RIP1/RIP3, and c-FLIPs were markedly elevated in the brains of CBE-treated RIP3+/−mice, and these results were similar to those obtained in the Gbaflox/flox; nestin-Cre mouse model.87 Researchers observed improvements in motor coordination and lifespan in CBE-treated RIP3−/− mice than CBE-treated RIP3+/− mice before appearance of neuronal loss but after appearance of neuroinflammation, which were accompanied by markedly fewer activated microglia in layer V of the cortex in CBE-treated RIP3+/− mice.87 These results implicate that RIP3 pathway may participate in neuroinflammation. This study indicates that necroptosis and neuroinflammation are both involved in the pathway of pathological events in severe forms of GD, and that RIP3 is a key factor of necroptotic cell death but also participate in the pathological processes of neuroinflammation. The role of necroptosis in GD merits further investigation.

Conclusions

Necroptosis is a novel form of programmed necrosis that can be triggered by a variety of stimuli from extracellular and intracellular. The RIP1-RIP3-MLKL necrosome plays a critical role in the initiation of necroptotic cell death. Increasing evidence suggests that inhibition of necroptosis can confer neuroprotective effect in neurodegenerative disorders, therefore indicating a promising therapeutic target. Continued investigation into the role of necroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases could provide invaluable insights into the neuron death mechanisms. Given that necroptosis may interact with other pathogenic mechanism such as apoptosis and inflammation in neurodegenerative disorders, combination therapies will be required to target the multiple activated cell death pathways to prevent the death of neurons.

To date, no suitable inhibitors of the necroptosis pathway with activity in the brains of mice or humans have been identified. Although Nec-1 crosses the blood-brain barrier, it has a short half-life of about 1 h, making it unsuitable for treatment of chronic diseases.76 According to the study of Takahashi et al., Nec-1s might be a perfect alternative inhabitor to RIP1 and offer a promising therapeutic option for the treatment of pathological conditions involving RIP1/RIP3-dependent necroptosis.30 Moreover, emerging evidence showed that RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL are not the special marker of necroptosis, but also invloved in other pathways such as inflammation.7, 92 Researches that studied the role of necroptosis in disease using inhibitor of RIP1, RIP3, or MLKL may not precise as thought. Many conclusions drawn on the use of RIP1/RIP3/MLKL inhibitors or deficiency to explore the role of ncroptosis in neuronal diseases without premeditate the facts that they may be involved in other pathological process may require reevaluation. RIP3 inhibitors31 and an inhibitor of MLKL9 have demonstrate effect in vitro and in vivo. Development of such croptotic signaling inhibitors may pave the way for alternative therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative diseases, for which innovative treatments are urgently required.

References

Healy E, Dempsey M, Lally C, Ryan MP . Apoptosis and necrosis: mechanisms of cell death induced by cyclosporine A in a renal proximal tubular cell line. Kidney Int 1998; 54: 1955–1966.

Lalaoui N, Lindqvist LM, Sandow JJ, Ekert PG . The molecular relationships between apoptosis, autophagy and necroptosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 39: 63–69.

Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P . Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15: 135–147.

Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol 2005; 1: 112–119.

Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, Zhang N, Lu BJ, Lin SC et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 2009; 325: 332–336.

He S, Wang L, Miao L, Wang T, Du F, Zhao L et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell 2009; 137: 1100–1111.

Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 2009; 137: 1112–1123.

Zhao J, Jitkaew S, Cai Z, Choksi S, Li Q, Luo J et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 5322–5327.

Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012; 148: 213–227.

Vanden Berghe T, Grootjans S, Goossens V, Dondelinger Y, Krysko DV, Takahashi N et al. Determination of apoptotic and necrotic cell death in vitro and in vivo. Methods 2013; 61: 117–129.

Koshinuma S, Miyamae M, Kaneda K, Kotani J, Figueredo VM . Combination of necroptosis and apoptosis inhibition enhances cardioprotection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Anesth 2014; 28: 235–241.

Challa S, Chan FK . Going up in flames: necrotic cell injury and inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; 67: 3241–3253.

de Almagro MC, Vucic D . Necroptosis: pathway diversity and characteristics. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 39: 56–62.

Micheau O, Tschopp J . Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 2003; 114: 181–190.

Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T, Kroemer G . Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11: 700–714.

Rickard JA, O'Donnell JA, Evans JM, Lalaoui N, Poh AR, Rogers T et al. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell 2014; 157: 1175–1188.

Newton K, Dugger DL, Wickliffe KE, Kapoor N, de Almagro MC, Vucic D et al. Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science 2014; 343: 1357–1360.

Polykratis A, Hermance N, Zelic M, Roderick J, Kim C, Van TM et al. Cutting edge: RIPK1 Kinase inactive mice are viable and protected from TNF-induced necroptosis in vivo. J Immunol 2014; 193: 1539–43.

Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B, Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M et al. cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol Cell 2011; 43: 449–463.

McComb S, Cheung HH, Korneluk RG, Wang S, Krishnan L, Sad S . cIAP1 and cIAP2 limit macrophage necroptosis by inhibiting Rip1 and Rip3 activation. Cell Death Differ 2012; 19: 1791–1801.

Dondelinger Y, Aguileta MA, Goossens V, Dubuisson C, Grootjans S, Dejardin E et al. RIPK3 contributes to TNFR1-mediated RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptosis in conditions of cIAP1/2 depletion or TAK1 kinase inhibition. Cell Death Differ 2013; 20: 1381–1392.

Hitomi J, Christofferson DE, Ng A, Yao J, Degterev A, Xavier RJ et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell 2008; 135: 1311–1323.

Vanlangenakker N, Vanden Berghe T, Bogaert P, Laukens B, Zobel K, Deshayes K et al. cIAP1 and TAK1 protect cells from TNF-induced necrosis by preventing RIP1/RIP3-dependent reactive oxygen species production. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18: 656–665.

Moquin DM, McQuade T, Chan FK . CYLD deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFalpha-induced necrosome to facilitate kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e76841.

Lin Y, Devin A, Rodriguez Y, Liu ZG . Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev 1999; 13: 2514–2526.

Tsuchiya Y, Nakabayashi O, Nakano H . FLIP the Switch: Regulation of Apoptosis and Necroptosis by cFLIP. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16: 30321–30341.

Sun X, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Fairbrother WJ, Dixit VM . Identification of a novel homotypic interaction motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein (RIP) by RIP3. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 9505–9511.

Wu XN, Yang ZH, Wang XK, Zhang Y, Wan H, Song Y et al. Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3 hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis. Cell Death Differ 2014; 21: 1709–1720.

Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch'en IL, Korkina O, Teng X et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol 2008; 4: 313–321.

Takahashi N, Duprez L, Grootjans S, Cauwels A, Nerinckx W, DuHadaway JB et al. Necrostatin-1 analogues: critical issues on the specificity, activity and in vivo use in experimental disease models. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3: e437.

Mandal P, Berger SB, Pillay S, Moriwaki K, Huang C, Guo H et al. RIP3 induces apoptosis independent of pronecrotic kinase activity. Mol Cell 2014; 56: 481–495.

Liao D, Sun L, Liu W, He S, Wang X, Lei X . Necrosulfonamide inhibits necroptosis by selectively targeting the mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein. Med Chem Commun 2014; 5: 333.

Wu J, Huang Z, Ren J, Zhang Z, He P, Li Y et al. Mlkl knockout mice demonstrate the indispensable role of Mlkl in necroptosis. Cell Res 2013; 23: 994–1006.

Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell 2014; 54: 133–146.

Murphy JM, Czabotar PE, Hildebrand JM, Lucet IS, Zhang JG, Alvarez-Diaz S et al. The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity 2013; 39: 443–453.

Conos SA, Chen KW . Active MLKL triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome in a cell-intrinsic manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114: E961–e9.

Gutierrez KD, Davis MA . MLKL Activation Triggers NLRP3-Mediated Processing and Release of IL-1beta Independently of Gasdermin-D. J Immunol 2017; 198: 2156–2164.

Cai Z, Jitkaew S, Zhao J, Chiang HC, Choksi S, Liu J et al. Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16: 55–65.

Chen X, Li W, Ren J, Huang D, He WT, Song Y et al. Translocation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein to plasma membrane leads to necrotic cell death. Cell Res 2014; 24: 105–121.

Pasparakis M, Vandenabeele P . Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature 2015; 517: 311–320.

Silke J, Rickard JA, Gerlic M . The diverse role of RIP kinases in necroptosis and inflammation. Nat Immunol 2015; 16: 689–697.

Dondelinger Y, Declercq W, Montessuit S, Roelandt R, Goncalves A, Bruggeman I et al. MLKL compromises plasma membrane integrity by binding to phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Cell Rep 2014; 7: 971–981.

You Z, Savitz SI, Yang J, Degterev A, Yuan J, Cuny GD et al. Necrostatin-1 reduces histopathology and improves functional outcome after controlled cortical impact in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 1564–1573.

Zhu S, Zhang Y, Bai G, Li H . Necrostatin-1 ameliorates symptoms in R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Cell Death Dis 2011; 2: e115.

Ito Y, Ofengeim D, Najafov A, Das S, Saberi S, Li Y et al. RIPK1 mediates axonal degeneration by promoting inflammation and necroptosis in ALS. Science 2016; 353: 603–608.

Jiang T, Yu JT, Tan L . Novel disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 31: 475–492.

Yang SH, Lee DK, Shin J, Lee S, Baek S, Kim J et al. Nec-1 alleviates cognitive impairment with reduction of Abeta and tau abnormalities in APP/PS1 mice. EMBO Mol Med 2017; 9: 61–77.

Qinli Z, Meiqing L, Xia J, Li X, Weili G, Xiuliang J et al. Necrostatin-1 inhibits the degeneration of neural cells induced by aluminum exposure. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2013; 31: 543–555.

Obulesu M, Rao DM . Animal models of Alzheimer's disease: an understanding of pathology and therapeutic avenues. Int J Neurosci 2010; 120: 531–537.

Zhang QL, Niu Q, Ji XL, Conti P, Boscolo P . Is necroptosis a death pathway in aluminum-induced neuroblastoma cell demise? Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2008; 21: 787–796.

Walton JR . An aluminum-based rat model for Alzheimer's disease exhibits oxidative damage, inhibition of PP2A activity, hyperphosphorylated tau, and granulovacuolar degeneration. J Inorg Biochem 2007; 101: 1275–1284.

Savory J, Herman MM, Ghribi O . Mechanisms of aluminum-induced neurodegeneration in animals: Implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2006; 10: 135–144.

Bharathi, Shamasundar NM, Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Dhanunjaya Naidu M, Ravid R, Rao KS . A new insight on Al-maltolate-treated aged rabbit as Alzheimer's animal model. Brain Res Rev 2006; 52: 275–292.

Inden M, Kitamura Y, Takeuchi H, Yanagida T, Takata K, Kobayashi Y et al. Neurodegeneration of mouse nigrostriatal dopaminergic system induced by repeated oral administration of rotenone is prevented by 4-phenylbutyrate, a chemical chaperone. J Neurochem 2007; 101: 1491–1504.

Lynch-Day MA, Mao K, Wang K, Zhao M, Klionsky DJ . The role of autophagy in Parkinson's disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a009357.

Arduino DM, Esteves AR, Cardoso SM . Mitochondria drive autophagy pathology via microtubule disassembly: a new hypothesis for Parkinson disease. Autophagy 2013; 9: 112–114.

Pan PY, Yue Z . Genetic causes of Parkinson's disease and their links to autophagy regulation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014; 20 (Suppl 1): S154–S157.

Wu JR, Wang J, Zhou SK, Yang L, Yin JL, Cao JP et al. Necrostatin-1 protection of dopaminergic neurons. Neural Regen Res 2015; 10: 1120–1124.

Necrostatin-1 protection of dopaminergic neurons, Lindner MD, Winn SR, Baetge EE, Hammang JP, Gentile FT et al. Implantation of encapsulated catecholamine and GDNF-producing cells in rats with unilateral dopamine depletions and parkinsonian symptoms. Exp Neurol 1995; 132: 62–76.

Smith CC, Yellon DM . Necroptosis, necrostatins and tissue injury. J Cell Mol Med 2011; 15: 1797–1806.

Kanning KC, Kaplan A, Henderson CE . Motor neuron diversity in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 2010; 33: 409–440.

Re DB, Le Verche V, Yu C, Amoroso MW, Politi KA, Phani S et al. Necroptosis drives motor neuron death in models of both sporadic and familial ALS. Neuron 2014; 81: 1001–1008.

Grad LI, Fernando SM, Cashman NR . From molecule to molecule and cell to cell: prion-like mechanisms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis 2015; 77: 257–265.

Li M, Ona VO, Guegan C, Chen M, Jackson-Lewis V, Andrews LJ et al. Functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in an ALS transgenic mouse model. Science 2000; 288: 335–339.

Beeldman E, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, van Maarle MC, van Ruissen F, Baas F . A Dutch family with autosomal recessively inherited lower motor neuron predominant motor neuron disease due to optineurin mutations. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2015; 16: 410–411.

Cirulli ET, Lasseigne BN, Petrovski S, Sapp PC, Dion PA, Leblond CS et al. Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science 2015; 347: 1436–1441.

Maruyama H, Morino H, Ito H, Izumi Y, Kato H, Watanabe Y et al. Mutations of optineurin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 2010; 465: 223–226.

Ofengeim D, Ito Y, Najafov A, Zhang Y, Shan B, DeWitt JP et al. Activation of necroptosis in multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep 2015; 10: 1836–1849.

Teng X, Degterev A, Jagtap P, Xing X, Choi S, Denu R et al. Structure-activity relationship study of novel necroptosis inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2005; 15: 5039–5044.

Soliman H, Mediavilla-Varela M, Antonia S . Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: is it an immune suppressor? Cancer J (Sudbury) 2010; 16: 354–359.

Zuccato C, Valenza M, Cattaneo E . Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutical targets in Huntington's disease. Physiol Rev 2010; 90: 905–981.

Ehrlich ME, Conti L, Toselli M, Taglietti L, Fiorillo E, Taglietti V et al. ST14A cells have properties of a medium-size spiny neuron. Exp Neurol 2001; 167: 215–226.

Wang X, Zhu S, Pei Z, Drozda M, Stavrovskaya IG, Del Signore SJ et al. Inhibitors of cytochrome c release with therapeutic potential for Huntington's disease. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 9473–9485.

Varma H, Cheng R, Voisine C, Hart AC, Stockwell BR . Inhibitors of metabolism rescue cell death in Huntington's disease models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 14525–14530.

Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C et al. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell 1996; 87: 493–506.

Jagtap PG, Degterev A, Choi S, Keys H, Yuan J, Cuny GD . Structure-activity relationship study of tricyclic necroptosis inhibitors. J Med Chem 2007; 50: 1886–1895.

Friedlander RM . Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1365–1375.

Han W, Xie J, Li L, Liu Z, Hu X . Necrostatin-1 reverts shikonin-induced necroptosis to apoptosis. Apoptosis 2009; 14: 674–686.

Patterson M Niemann-Pick Disease Type C. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH et al, (eds). GeneReviews(R) 1993.

Wassif CA, Cross JL, Iben J, Sanchez-Pulido L, Cougnoux A, Platt FM et al. High incidence of unrecognized visceral/neurological late-onset Niemann-Pick disease, type C1, predicted by analysis of massively parallel sequencing data sets. Genet Med 2016; 18: 41–48.

Wraith JE, Vecchio D, Jacklin E, Abel L, Chadha-Boreham H, Luzy C et al. Miglustat in adult and juvenile patients with Niemann-Pick disease type C: long-term data from a clinical trial. Mol Genet Metab 2010; 99: 351–357.

Cougnoux A, Cluzeau C, Mitra S, Li R, Williams I, Burkert K et al. Necroptosis in Niemann-Pick disease, type C1: a potential therapeutic target. Cell Death Dis 2016; 7: e2147.

Yanjanin NM, Velez JI, Gropman A, King K, Bianconi SE, Conley SK et al. Linear clinical progression, independent of age of onset, in Niemann-Pick disease, type C. American journal of medical genetics Part B. Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010; 153B: 132–140.

Futerman AH, van Meer G . The cell biology of lysosomal storage disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5: 554–565.

Capablo Liesa JL, de Cabezon AS, Alarcia Alejos R, Ara Callizo JR . Clinical characteristics of the neurological forms of Gaucher's disease. Med Clin 2011; 137 (Suppl 1): 6–11.

Enquist IB, Lo Bianco C, Ooka A, Nilsson E, Mansson JE, Ehinger M et al. Murine models of acute neuronopathic Gaucher disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 17483–17488.

Vitner EB, Salomon R, Farfel-Becker T, Meshcheriakova A, Ali M, Klein AD et al. RIPK3 as a potential therapeutic target for Gaucher's disease. Nat Med 2014; 20: 204–208.

Hughes MA, Powley IR, Jukes-Jones R, Horn S, Feoktistova M, Fairall L et al. Co-operative and Hierarchical Binding of c-FLIP and Caspase-8: A Unified Model Defines How c-FLIP Isoforms Differentially Control Cell Fate. Mol Cell 2016; 61: 834–849.

Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P . The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity 1998; 8: 297–303.

Kanfer JN, Stephens MC, Singh H, Legler G . The Gaucher mouse. Prog Clin Biol Res 1982; 95: 627–644.

Farfel-Becker T, Vitner EB, Futerman AH . Animal models for Gaucher disease research. Dis Models Mech 2011; 4: 746–752.

Duprez L, Takahashi N, Van Hauwermeiren F, Vandendriessche B, Goossens V, Vanden Berghe T et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity 2011; 35: 908–918.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by grants 81530037 and 81471158 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (to Dr Yuming Xu) and grant U1404311 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (to Dr Changhe Shi).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by A Oberst

Rights and permissions

Cell Death and Disease is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Tang, Mb., Luo, Hy. et al. Necroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases: a potential therapeutic target. Cell Death Dis 8, e2905 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.286

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.286

This article is cited by

-

Mediators of necroptosis: from cell death to metabolic regulation

EMBO Molecular Medicine (2024)

-

Effects of Manganese and Iron, Alone or in Combination, on Apoptosis in BV2 Cells

Biological Trace Element Research (2024)

-

Role of the P2 × 7 receptor in neurodegenerative diseases and its pharmacological properties

Cell & Bioscience (2023)

-

MLKL deficiency alleviates neuroinflammation and motor deficits in the α-synuclein transgenic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2023)

-

RIP3-mediated microglial necroptosis promotes neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy

Cell Death & Disease (2023)