Abstract

Wingless-related MMTV integration site (WNT) proteins and several other components of the WNT signalling pathway are expressed in the murine testes. However, mice mutant for WNT signalling effector β-catenin using different Cre drivers have phenotypes that are inconsistent with each other. The complexity and overlapping expression of WNT signalling cascades have prevented researchers from dissecting their function in spermatogenesis. Depletion of the Gpr177 gene (the mouse orthologue of Drosophila Wntless), which is required for the secretion of various WNTs, makes it possible to genetically dissect the overall effect of WNTs in testis development. In this study, the Gpr177 gene was conditionally depleted in germ cells (Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre; Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre) and Sertoli cells (Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre). No obvious defects in fertility and spermatogenesis were observed in these three Gpr177 conditional knockout (cKO) mice at 8 weeks. However, late-onset testicular atrophy and fertility decline in two germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice were noted at 8 months. In contrast, we did not observe any abnormalities of spermatogenesis and fertility, even in 8-month-old Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre mice. Elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was detected in Gpr177 cKO germ cells and Sertoli cells and exhibited an age-dependent manner. However, significant increase in the activity of Caspase 3 was only observed in germ cells from 8-month-old germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout mice. In conclusion, GPR177 in Sertoli cells had no apparent influence on spermatogenesis, whereas loss of GPR177 in germ cells disrupted spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner via elevating ROS levels and triggering germ cell apoptosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

WNT signalling is a highly conserved cell-to-cell communication mechanism that consists of a canonical (WNT/β-catenin pathway) and noncanonical branch (reviewed in Logan and Nusse1). WNT signalling has essential functions in development and tissue homoeostasis, and the misregulation of WNT signalling has been implicated in several pathological states (reviewed in Cadigan2). The vertebrate WNT family consists of 19 secreted cysteine-rich glycoproteins, among which WNT1,3 WNT3,4 WNT3a,5 WNT4,6 WNT5a,7 WNT7a,8 WNT10b9 and WNT1110 have been reported in the developing testes or in the testes of adult male rodents and humans. Several other components of the canonical WNT signalling pathway, such as DVL1,11 FZ9,12 β-catenin,13 NKD1,14 DKKL115 and APC,16 have also been detected in testis tissues.

Gene knockout mouse models have provided information about WNTs and WNT signalling. During the embryonic stage of mouse development, WNT3 and WNT3A regulate primordial germ cell (PGC) specification and early expansion.17, 18 WNT5A-ROR2 serves as an important cue for PGC migration; loss of Wnt5a disrupts PGC migration into the genital ridge.19, 20 It is also well established that WNT signalling mainly plays a negative role in testis determination and proper repression of WNT signalling by the SRY/SOX9/FGF9 pathway is important for normal sexual differentiation.21, 22 Constitutive activation of WNT signalling effector β-catenin in Sertoli cells causes male infertile phenotypes, including testis cord disruption, inhibition of Müllerian duct regression and germ cell apoptosis.23, 24 Further study suggests that constitutive activated β-catenin signalling in Sertoli cells downregulates spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) activity via the paracrine factor WNT4.25 In contrast, Sertoli cell-specific knockout of β-catenin causes no detectable abnormalities.23 WNT3A/β-catenin signalling was reported to stimulate proliferation, morphological changes and cell migration of a spermatogonial cell line in vitro.5, 9 WNT5A, secreted from Sertoli cells, has been shown to support SSC maintenance through β-catenin-independent JNK signalling.7 Post-meiotic male germ cell-specific deletion of β-catenin using Prm1-Cre results in significantly reduced sperm count, increased germ cell apoptosis and impaired fertility.26 However, Rivas et al. suggested that conditional deletion of β-catenin using Stra8-Cre (express only in males beginning at postnatal day 327) has no effect on male fertility.28 In a recent article,29 Takase et al. reported that WNT6 secreted by Sertoli cells activates WNT/β-catenin signalling in undifferentiated spermatogonia, including SSCs, which mediate the proliferation but not the maintenance of undifferentiated spermatogonia.

Collectively, previous studies have suggested that WNT signalling and WNTs play multiple roles in spermatogenesis, but there are still the following problems: (1) the conclusions about the function of WNT/β-catenin in germ cells are inconsistent with each other;26, 28, 29 (2) the overlapping expression pattern of the various WNTs and their functional redundancy obscure the true consequences of removing individual Wnt genes; and (3) β-catenin does play a central role in the canonical WNT pathway, but it also serves as a membrane protein of the cell junction complex.30

WNTs are secreted as glycoproteins from WNT-producing cells into the extracellular milieu.31 In 2006, Bänziger et al.32 and Bartscherer et al.33 identified a novel WNT pathway component, Wntless (WLS), and showed that it is responsible for the secretion of WNT proteins from signalling cells. Loss of WLS function has no effect on other signalling pathways, but it appears to impede all of the WNT signals.32, 33 Retromer retrieves endocytosed WLS from endosomes and recycles it back to the trans-Golgi network for its further function in WNT secretion.34 Accordingly, the conditional knockout (cKO) mouse models of Gpr177, the mouse orthologue of Drosophila Wls, is more appropriate than other established models related to β-catenin for the study of the role of WNT singalling (both canonical and noncanonical) and WNTs.

Mice homozygous for Gpr177 (Gpr177−/−) die in the embryonic stage due to defects in body axis establishment.35 Carpenter et al.36 generated mice with a conditional null allele for Gpr177 (recombination of the loxP sites using Cre resulting in the removal of exon 1) and showed that GPR177 is essential for the development of brain and pancreas. Fu et al.37 created a novel conditional Gpr177 knockout mouse line (loxP sites flanking exon 3) and observed that the loss of GPR177 in WNT1-expressing cells causes mid/hindbrain and craniofacial defects, which resemble the double knockout of WNT1 and WNT3a as well as β-catenin deletion in the WNT1-expressing cells. Zhu et al.38 generated a different Gpr177 cKO mouse line carrying an exon 3-floxed allele and showed that GPR177-mediated WNTs regulate early patterning along the three axes of the limb bud and also sustain cell proliferation and survival of distal limb mesenchyme. Sebsequently, these Gpr177 cKO mouse lines have been utilised to investigate the roles of WNT signalling and WNTs in a variety of tissues, such as embryonic hair follicles, fungiform placodes and teeth.39, 40, 41, 42

Because the Gpr177 mRNA level is expressed in mouse testis43 and the role of WNT signalling in spermatogenesis is still unclear, we generated and analysed germ cell-specific (Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre) and the Sertoli cell-specific (Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre) Gpr177 cKO mice. We observed that selective loss of Gpr177 in germ cells or Sertoli cells blocks the secretion of cell-specific WNT ligands. GPR177 in Sertoli cells has no apparent influence on spermatogenesis, whereas germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice exhibit an age-dependent reproductive phenotype: fertile when young and subfertile when older. We further suggest that oxidative stress is involved in age-dependent spermatogenic damage of germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice.

Results

GPR177 expression in mouse testes

The findings of a previous study suggest that Gpr177 mRNA is expressed ubiquitously.43 In this study, we observed that GPR177 was expressed in many mouse tissues, including the spleen, lung, kidney, thymus, stomach, brain and testes, using western blot analysis (Figure 1a). Furthermore, the protein level of GPR177 in testis did not obviously differ between embryonic day (E) 15.5 and postnatal days (PND) 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 56 (Figure 1b). To evaluate GPR177 expression in different testicular cells, we assessed the GPR177 protein level in W/Wv testes (lacking endogenous germ cells), W/Wv recipient testes after SSC transplantation, freshly isolated Sertoli cells, germ cells and interstitial cells from adult mouse testes. GPR177 was highly expressed in germ cells and Sertoli cells, with little expression in interstitial cells (Figure 1c). The expression level of GPR177 protein was higher in W/Wv recipient testes after SSC transplantation than in W/Wv testes (Figure 1c). Immunofluorescence staining in E15.5 and PND56 testes further showed that GPR177 was visibly present in several testicular cell types, including germ cells and Sertoli cells (Figure 1d).

GPR177 protein level and localisation in mouse testes. (a) Expression of GPR177 in mouse tissues, including spleen, lung, kidney, thymus, stomach, brain and testes by western blot. (b) Expression of GPR177 in testes at different developmental stages, including E15.5, PND 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 56. (c) Protein level of GPR177 in W/Wv testes, W/Wv recipient testes after SSC transplantation, and isolated Sertoli, germ and interstitial cells. β-Tubulin served as a protein loading control in (a–c). (d) The cellular localisation of GPR177 in sections of testes from E15.5 and PND56 mice was displayed by immunofluorescent staining. The nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). The images shown were representative results of experiments that were repeated three times using samples from different sets of testes, which yielded similar results. Scale bars, 50 μm

Efficient and specific disruption of Gpr177

To assess the cell type-specific function of GPR177 during spermatogenesis, we generated mice in which the Gpr177 gene was specifically disrupted in germ cells using Mvh-Cre (Figure 2a) or Stra8-Cre (Figure 2b) and Sertoli cells using Amh-Cre (Figure 2c). Genotyping of the mice was performed by PCR using specific primers to distinguish wild-type or floxP alleles and different Cre bands. Gpr177 deletion efficiency in germ cells and Sertoli cells was assessed by detecting the Gpr177 mRNA level in testis, germ cells and Sertoli cells. As expected, we observed a significant reduction in Gpr177 mRNA levels in both whole testis lysate and isolated germ cells from Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre (Figure 2d) and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre testes (Figure 2e). Similarly, the Gpr177 mRNA level was significantly reduced in both whole testis lysate and isolated Sertoli cells from Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes (Figure 2f).

Targeted disruption of the Gpr177 gene. (a–c) Hybrid scheme used to develop Gpr177 cKO mice. Mice carrying a targeted Gpr177 allele (LoxP sites flank exon 3 of the Gpr177 allele) were crossed with Mvh-Cre or Stra8-Cre or Amh-Cre transgenic mice to selectively delete Gpr177. The gene knockout was confirmed by PCR genotyping. The genomic DNA isolated from the mouse tails was amplified with primer pairs specific for the wild-type (+) (~100 bp) and flox alleles (~200 bp) or different Cre bands (Mvh-Cre: 240 bp; Stra8-Cre: 326 bp and Amh-Cre: ~100 bp). (d–f) qRT-PCR analysis showing the conditional loss of Gpr177 mRNA in total testis extracts, germ cell or Sertoli cell extracts of three Gpr177 cKO mice. Gapdh served as the internal control gene. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

GPR177 is responsible for secretion of WNT proteins

WLS/GPR177 is required for the secretion of WNT proteins from signalling cells. We postulated that selective loss of Gpr177 in germ cells and Sertoli cells would block the secretion of germ cell-specific and Sertoli cell-specific WNT proteins, respectively. Thus, extracellular secretion of WNT proteins, as examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), was detected in supernatants of germ cells or Sertoli cells from control and Gpr177 cKO testes. Using qRT-PCR, we observed that Wnt3, Wnt3a and Wnt7a were predominantly expressed in germ cells (Supplementary Figures S1a and b), while Sertoli cells mainly expressed several Wnts, including Wnt4, Wnt6 and Wnt11 (Supplementary Figures S1a and c), which is consistent with previous studies.10, 29 We observed that secreted protein levels of WNT3, WNT3A and WNT7A were significantly decreased in culture supernatants of germ cells from two germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout testes, but not from Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes (Figures 3a–c). In addition, loss of Gpr177 in Sertoli cells inhibits extracellular secretion of WNT4, WNT6 and WNT11 by Sertoli cells (Figures 3d–f).

Loss of Gpr177 blocked the extracellular secretion of WNT proteins. (a– c) Protein levels of WNT3 (a), WNT3A (b) and WNT7A (c) in germ cell culture supernatants from control, Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre; Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre and Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes. (d–f) Secreted WNT4 (d), WNT6 (e) and WNT11 (f) examined by ELISA methods were observed in supernatants of Sertoli cells from control and three Gpr177 cKO testes. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. **P<0.01

Normal spermatogenesis in Gpr177 cKO mice at 8 weeks

After successfully generating two germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout mouse models, we investigated the role of GPR177 in germ cells. In 8-week-old cKO mice, there were no overt abnormalities in testis weight (127±2 mg in wild-type mice and 110±7 mg in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice; 122±2 mg in wild-type mice and 114±6 mg in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (Figure 4a), pregnancy rate (95% in wild-type mice and 90% in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice; 95% in wild-type mice and 95% in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (Figure 4b) and litter size (11.6±0.2 in wild-type mice and 10.7±0.3 in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice; 11.8±0.2 in wild-type mice and 11.4±0.3 in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (Figure 4c). Furthermore, Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre testes (Figures 5d–f), Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre testes (Figures 5j–l) and their respective littermate control testes (Figures 5a–c, g–i) exhibited typical seminiferous tubule morphology with all stages of spermatogenic cells (from spermatogonia to spermatozoa) at 8 weeks, indicating that spermatogenesis was normal in germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout males. The same conclusion was drawn from the immunofluorescence results of staining germ cell-specific marker MVH in the testes and spermatozoa-specific marker AQP3 in the cauda epididymis of Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre males (Supplementary Figures S2b and h) and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre males (Supplementary Figures S2d and j) at 8 weeks.

Eight-week-old Gpr177 cKO male mice were fertile. (a) Testis weights were examined. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. (b) The pregnancy rate was calculated as the ratio of the number of pregnant females to the number of successfully mating females. (c) When calculating the average litter size, only the females that generated pups were included. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M.

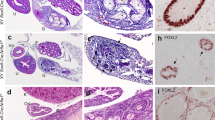

Testis and cauda epididymis morphology of 8-week-old Gpr177 cKO mice. (a–r) Testicular and cauda epididymal sections stained with H&E. No overt morphological abnormalities were observed in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre (d–f), Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre (j–l) and Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre (p–r) mice relative to their respective littermate controls (a–c, g–i, m–o). The images shown are representative results of experiments that were repeated three times using samples from different sets of testes, which yielded similar results. Scale bars in the first and third lines, 50 μm. Scale bars in the second line, 100 μm

To test whether Sertoli cell-specific Gpr177 deletion causes defects in fertility, we bred Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre males with wild-type females. The testis weight (126±2 mg in wild-type mice and 124±3 mg in Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre mice), pregnancy rate (100% in wild-type mice and 95% in Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre mice) and number of pups per litter (11.9±0.2 in wild-type mice and 11.7±0.3 in Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre mice) were not significantly different between Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre males and their respective littermate control males at 8 weeks (Figures 4a–c), indicating normal fertility of Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre male mice. Furthermore, histological and immunofluorescence analysis of Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes did not identify any major structural defects in testis morphology and spermatogenesis (Figures 5p–r and Supplementary Figures S2f and l).

Late-onset testicular atrophy and fertility decline in germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice

The spermatogenesis and fertility of Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice were indistinguishable from those of control mice at 8 weeks (above, Figures 4 and 5). However, these two germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout mice developed age-dependent testicular atrophy. By 8 months of age, the average weight of a Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre testis was approximately 59% of that of a control testis (124±2 mg in wild-type mice and 73±4 mg in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice) (P<0.05), while the average weight of a Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre testis was approximately 62% of that of a control testis (122±1 mg in wild-type mice and 75±3 mg in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (P<0.05) (Figure 6a). Testicular atrophy in the cKO mice was accompanied by a significant decline in pregnancy rate (80% in control mice and 30% in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice; 85% in wild-type mice and 40% in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (Figure 6b) and litter size (10.3±0.2% in wild-type mice and 7.6±0.3% in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre mice; 9.8±0.3% in wild-type mice and 7.0±0.3% in Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre mice) (Figure 6c) at 8 months. Observation of the mating behaviour of Gpr177 cKO males showed that they copulated with females at a rate comparable to control males, which indicated that behavioural factors were not the cause of the reduced fertility. H&E staining examination of the seminiferous epithelium of Gpr177 cKO mice revealed some histological abnormalities. The most obvious of these abnormalities was epithelial vacuolisation in some tubules, which were devoid of spermatocytes and spermatids and were evident in 8-month-old Gpr177 cKO mice (Figure 7a). As the mouse age increased, the percentage of tubules with abnormal spermatogenesis significantly increased in Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh8-Cre males (6.2±0.8% at 7 months, 15.5±0.4% at 8 months, 16.9±0.4% at 9 months and 24.2±0.6% at 10 months) and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre males (3.2±0.4% at 7 months, 11.1±0.6% at 8 months, 13.8±0.8% at 9 months and 20.3±0.8 at 10 months), compared with their controls (0% at 7 months, 2.5±0.2% at 8 months, 2.1±0.2% at 9 months and 3.6±0.2% at 10 months) (Figure 7b). In contrast, we did not observe obviously abnormal spermatogenesis or fertility decline even in aged (7- to 10-month-old) Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre mice (Figures 6 and 7).

Eight-month-old germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout male mice were subfertile. (a) Testis weights were examined. (b) The pregnancy rate was calculated as the ratio of the number of pregnant females to the number of successfully mating females. (c) When calculating the average litter size, only the females that generated pups were included. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05

Testis morphology of 8-month-old Gpr177 cKO mice. (a) Testicular sections were stained with H&E. Stars indicated tubules with abnormal spermatogenesis. The images shown were representative results of experiments that were repeated three times using samples from different sets of testes, which yielded similar results. Scale bars, 100 μm. (b) The percentage of tubules with abnormal spermatogenesis was counted from month 3 to month 10. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05

Oxidative stress is involved in age-dependent spermatogenic damage

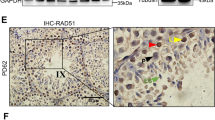

Given that elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) impairs spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner, we examined the status of ROS and apoptosis in different cell types from control and Gpr177 cKO testes at both 8 weeks and 8 months. As shown in Figure 8a, a significant increase of ROS level was observed in germ cells from Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre and Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre testes at 8 weeks, compared with germ cells from control and Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes at the same age. Selective loss of Gpr177 in Sertoli cells promoted a significant increase of ROS level in Sertoli cells at 8 weeks (Figure 8b). These data suggest that blocking WNT secretion by Gpr177 cKO causes increase of oxidative stress in corresponding cells from adult (8-week-old) testes. Furthermore, elevation of ROS exhibited an age-dependent manner. We observed that the ROS level was significantly increased in germ cells (Figure 8c) and Sertoli cells (Figure 8d) from 8-month-old Gpr177 cKO testes, compared with cells from 8-week-old Gpr177 cKO testes. The activity of Caspase 3 in germ cells (Figure 8e) and Sertoli cells (Figure 8f) was similar between control and Gpr177 cKO testes at 8 weeks. However, selective loss of Gpr177 in germ cells caused significant increase in the activity of Caspase 3 at 8 months relative to 8 weeks (Figure 8g). In contrast, the activity of Caspase 3 in Sertoli cells from 8-month-old Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre testes was not statistically different from Gpr177-deficient Sertoli cells at 8 weeks (Figure 8h).

Status of ROS and apoptosis in germ and Sertoli cells from 8-week-old and 8-month-old Gpr177 testes. (a) ROS level in germ cells from control, Gpr177 cKO testes at 8 weeks. (b) ROS level in Sertoli cells from control, Gpr177 cKO testes at 8 weeks. (c) ROS level in germ cells from 8-week-old and 8-month-old germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout testes. (d) ROS level in Sertoli cells from 8-week-old and 8-month-old Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre knockout testes. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of Caspase 3 activity in germ cells from control, Gpr177 cKO testes at 8 weeks. (f) Caspase 3 activity in Sertoli cells from control, Gpr177 cKO testes at 8 weeks. (g) Caspase 3 activity in germ cells from 8-week-old and 8-month-old germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout testes. (h) Caspase 3 activity in Sertoli cells from 8-week-old and 8-month-old Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre knockout testes. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05

Discussion

Cell–cell communication via WNT signalling represents a fundamental means by which animal development and homoeostasis are controlled. Components of the cellular machinery responsible for transducing WNT signals from the cell surface to the nucleus, which is mainly mediated by β-catenin, have been identified in receiving cells, but the identification of components associated with the events occurring in WNT-secreting cells is incomplete (reviewed by Logan and Nusse1). Importantly, recent studies have identified a novel WNT pathway component, Wntless (WLS), that promotes WNTs secretion from WNT-producing cells into the extracellular milieu.32, 33 WLS is evolutionarily and functionally conserved; seven-pass membrane protein, intriguingly, acts exclusively in WNT signal-sending cells. Accordingly, Gpr177 (mouse orthologue of Drosophila Wls) cKO mice are excellent models to study the role of WNT singalling (both canonical and noncanonical) and total WNTs.

Mice mutant for β-catenin using other Cre drivers have phenotypes that are inconsistent with each other. Germ cell-specific β-catenin knockout mediated by Stra8-Cre, which is expressed in differentiating spermatogonia at the onset of differentiation, did not cause a detectable phenotype.28 However, spermatid-specific β-catenin knockout mediated by Prm1-Cre has been shown to cause impaired fertility as a result of reduced sperm counts.26 Kerr et al.44 reported disrupted spermatogenesis in both loss- and gain-of-WNT signalling function experiments using AhCre. In a recent article, Takase et al.29 reported that WNT6 secreted by Sertoli cells activates WNT/β-catenin signalling and mediates the proliferation of undifferentiated spermatogonia. These researchers demonstrated that undifferentiated spermatogonia are WNT-responsive cells by taking advantage of genetic lineage tracing using the WNT target gene Axin2. We hypothesise that undifferentiated spermatogonia are not the only WNT-responsive cell population within the testes, because previous studies have demonstrated the expression and conditional deletion β-catenin in meiotic and post-meiotic germ cells.26, 28 Furthermore, the Axin2-LacZ reporter line used in the current study revealed different WNT-responsive cells than the Tcf/Lef-LacZ mouse reporter line.7 Conditional deletion of β-catenin in AXIN2-expressing cells upon tamoxifen injection reduced the proliferation of undifferentiated spermatogonia. Thus, the authors suggested that WNT/β-catenin signalling promotes stem cell proliferation. However, we hypothesise that the reduced proliferation could also be due to impaired cadherin-mediated adherens junctions rather than disrupted WNT/β-catenin signalling, based on the following evidence. First, although β-catenin plays a central role in the canonical WNT pathway, it also serves as a membrane protein in the cell junction complex.45, 46 Second, we found in current study that conditional deletion of the Gpr177 gene in Sertoli cells using Amh-Cre (blocking WNTs secretion from Sertoli cells) had no effect on spermatogenesis and male fertility. Additionally, the evidence that Sertoli cells secrete WNT6 as a paracrine signal for undifferentiated spermatogonia is insufficient. In addition to Sertoli cells, other somatic cell types contribute to the SSC niche, including Leydig cells,47 peritubular myoid cells48 and peritubular macrophages.49 Thus, WNT-producing cells are not limited to Sertoli cells. Wnt6 was shown to be specifically expressed in Sertoli cells, particularly in the basal compartment. However, using qRT-PCR, we observed that Sertoli cells express several Wnts, including, but not limited to, Wnt6 (Supplementary Figure S1). The generation of Sertoli cell-specific Wnt6 knockouts would be helpful to confirm this conclusion. Thus, these data are insufficient to draw the conclusion that Sertoli cells secrete WNT6 to activate canonical WNT signalling in undifferentiated spermatogonia.

Our study demonstrates that GPR177 in Sertoli cells has no apparent influence on spermatogenesis, whereas germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice exhibit an age-dependent reproductive phenotype: fertile when young and subfertile when older. We suggest that accumulated WNTs do harm to germ cells and oxidative stress and apoptosis are involved in age-dependent spermatogenic damage of germ cell-specific Gpr177 deletion mice. ROS has a dual role in reproductive systems, both beneficial and harmful depending on their nature and concentration as well as location and length of exposure.50, 51 The decline in male fertility with aging is associated with increasing oxidative damage in the male reproductive system. Mice lacking nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), or superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), or inner mitochondrial membrane peptidase 2-like (Immp2l) develop impaired spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner.52, 53, 54 In contrast, SSCs depleted of ROS stop proliferating, while enhanced self-renewal is observed when ROS levels are increased.55 Thus, ROS levels need to be tightly controlled in germ cells. In this study, we suggest that elevation of ROS level in germ cells triggers apoptotic signalling to disrupt spermatogenesis in aged (8-month-old) Gpr177-deficient germ cells. The reason why young (8-week-old) germ cell-specific Gpr177 knockout mice (germ cells also endure oxidative stress) exhibit normal spermatogenesis is still unclear. One of the main reasons is that ROS level in 8-week-old Gpr177-deficient germ cells was significantly lower than that in 8-month-old mutant germ cells (Figure 8c). Compared with germ cells, Sertoli cells seem to endure oxidative stress to a certain extent, because we did not observe significant apoptosis in even 8-month-old Gpr177-deficient Sertoli cells (Figures 8d and h).

Notably, two recent studies suggest that mammalian spermatozoa respond to WNT signals released from the epididymis and WNT signalling controls sperm maturation independent of β-catenin.56, 57 It is a novel way of WNT signalling in regulating spermatogenesis. We suggest that generation of cKO mice in which Gpr177 was specifically knocked out in epididymal cells (using Rnase10-Cre or Lcn5-Cre) could provide further evidence whether GPR177-mediated WNT secretion from epididymal cells act as an epididymal sperm maturation signal.

Material and Methods

Mice

All animal works were carried out in accordance with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). All the mice were maintained in a C57BL/6;129/SvEv mixed background. Gpr177flox/flox mice homozygous for a floxp allele of Gpr177 (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA, stock no. 012888), Mvh-Cre (The Jackson Laboratory, stock no. 006954), Stra8-Cre (The Jackson Laboratory, stock no. 008208) and Amh-Cre (The Jackson Laboratory, stock no. 007915) mice were used in the present study and were described previously.27, 38, 58, 59 W/Wv mice were introduced from The Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 000693) and SSC transplantation was performed as described previously.60

Fertility rate

Two- and eight-month-old Gpr177flox/flox, Mvh-Cre, Gpr177flox/flox, Stra8-Cre and Gpr177flox/flox, Amh-Cre males and their respective littermate controls were separately housed with wild-type C57BL/6 females (ratio=1:2) for 3 months. The pregnancy rate (no. of litter/mating) and litter size (no. of pup/litter) was recorded in each group. All mice were housed under controlled photoperiod conditions and supplied with food and ddH2O ad libitum.

Isolation of Sertoli, interstitial and spermatogenic cells

The method to isolate cells from the testes of adult mice was modified slightly based on previous reports.61, 62 Briefly, tubules without tunica albuginea were incubated in 1 mg/ml BSA containing 1mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and under shaking (100 r.p.m.) for 20 min in a 37 °C water bath. Tubules were collected by centrifugation at 40 × g, and the crude cell suspension was filtered through a 200-mesh nylon membrane. The cell suspension was separated in a discontinuous Percoll (Pharmacia, Shanghai, China) gradient of 30, 40, 50 and 60% at 800 × g for 20 min. A gradient fraction mainly containing interstitial cells between 50 and 60% layers (1.067–1.077 g/ml) was collected, washed once in culture medium and then plated in DMEM/F12. For germ cell and Sertoli cell isolation, precipitated seminiferous tubules mentioned above were dissociated and incubated with 1mg/ml collagenase IV, 1 mg/ml hyaluronidase, 1 mg/ml trypsin and 0.5 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM/F12 medium for 15 min at 37 °C in a shaker. Dispersed cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and washed twice. Then, cell suspension was cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with penicillin (100 UI/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and 10% FBS. This technique called panning is extremely efficient for the gross separation and purification of the germ cells. Sertoli cells were treated with a hypotonic solution (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4) for 1 min to remove the residual germ cells. Collect germ cells from suspension in culture medium and gently overlay the top of the prepared BSA gradient63 with the cell suspension. The gradient was centrifuged at 800 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The fractions at the 25–32% interface were collected. Cells were cultured at 34 °C in a mixture of 5% CO2:95% air for 18 h.

Histological examination and immunofluorescence

The control and Gpr177 cKO male mice were killed via cervical dislocation and the testes were immediately fixed in Bouin’s solution for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or in 4% formaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for immunofluorescence, as previously described.61, 64 In brief, tissue sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated, followed by antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer. The sections were blocked using a blocking buffer (donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) and incubated with primary antibodies against GPR177 (1:200; Santa Cruz, St. Louis, MO, USA, sc-133635), MVH (1:300; Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab13840) or AQP3 (1:400; kind gift from Dr. Qi Chen) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed and incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h and counterstained with DAPI (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) to identify the nuclei.

Quantitative (q)RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Dallas, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA samples were subjected to reverse transcription using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The reactions were run in triplicate in three independent experiments. The CT values for the samples were normalised to the corresponding Gapdh CT values, and relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method. The primer pair for Gpr177: forward (5′-TGGGAAGCAGTCTAGCCTCC-3′) and reverse (5′-GCAGCACAAGCCAAGGTGATA-3′). The primer pair for Gapdh: forward (5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGAT-3′) and reverse (5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGA-3′).

Western blot

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.61 Briefly, proteins were electrophoresed under reducing conditions in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were blocked in 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody, followed by incubation with the secondary antibody (anti-rabbit Dye 800CW; LI-COR, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The specific signals and the corresponding band intensities were evaluated using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (Odyssey, Berlin, Germany). The protein level was normalised and plotted against β-tubulin. The following antibodies were used in this study: rabbit anti-GPR177 (1/800; Santa Cruz, sc-133635) and rabbit anti-β-tubulin (1/3000; Abcam, 6046).

ELISA

The germ cells and Sertoli cells were isolated from control and Gpr177 cKO testes and cultured in DMEM/F12 with 10% serum as described above. Supernatants were collected and used for ELISA analysis for quantification of secreted WNT3 (CSB-EL026135MO), WNT3A (CSB-EL026136MO), WNT7A (CSB-EL026141MO), WNT4 (CSB-EL026137MO), WNT6 (CSB-EL026140MO) and WNT11 (CSB-EL026131MO) (CUSABIO, Wuhan, China) using the manufacturer’s instructions.

ROS assays

The generation of ROS in germ cells and Sertoli cells from control and Gpr177 cKO testes was measured using 5, and 6-chloromethyl-2′,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate ethyl ester (DCFH-DA) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a concentration of 5 mM for 30 min. This ester diffuses into cells where it is cleaved and trapped inside the cells as DCFH. DCFH is oxidised by ROS to 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein, which can be easily detected by its strong fluorescence.65 After washing the cells three times with PBS, the conversion of DCFH to dichlorofluorescein (DCF; green fluorescence) was measured using a flow cytometer (BD FACS Calibur; BD Pharmingen, St. Louis, MO, USA). Data were expressed as the percentage of the fluorescent cells.

Analysis of Caspase 3 activity

Caspase 3 activity was determined using PE active caspase 3 apoptosis kit (BD Pharmingen). Germ cells or Sertoli cells from control and Gpr177 cKO testes were resuspended in 0.5 ml Cytofix/Cytoperm solution for 20 min on ice and then incubated in 100 μl of Perm/Wash buffer containing 20 μl Caspase 3 antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Each sample was then added with 400 μl Perm/Wash buffer, and Caspase 3 activity signals were analysed by flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur; BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

Protein and mRNA levels, testis weights, ROS levels, Caspase 3 activity, fertility rate, litter size and percentage of tubules with abnormal spermatogenesis between control and Gpr177 cKO mice were analysed by using the Student’s t-test. Results are presented as mean±S.E.M. Statistical significance was set at *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations

- WNT:

-

wingless-related MMTV integration site

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

- PGC:

-

primordial germ cell

- SSC:

-

spermatogonial stem cell

- cKO:

-

conditional knockout

- E:

-

embyonic day

- PND:

-

postnatal day

- H&E:

-

hematoxylin and eosin

- PFA:

-

formaldehyde

- DCFH-DA:

-

5, and 6-chloromethyl-2′,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate ethyl ester.

References

Logan CY, Nusse R . The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004; 20: 781–810.

Cadigan KM . Wnt-beta-catenin signaling. Curr Biol 2008; 18: R943–R947.

Erickson RP, Lai LW, Grimes J . Creating a conditional mutation of Wnt-1 by antisense transgenesis provides evidence that Wnt-1 is not essential for spermatogenesis. Dev Genet 1993; 14: 274–281.

Katoh M . Molecular cloning and characterization of human WNT3. Int J Oncol 2001; 19: 977–982.

Yeh JR, Zhang X, Nagano MC . Indirect effects of Wnt3a/beta-catenin signalling support mouse spermatogonial stem cells in vitro. PLoS One 2012; 7: e40002.

Jeays-Ward K, Dandonneau M, Swain A . Wnt4 is required for proper male as well as female sexual development. Dev Biol 2004; 276: 431–440.

Yeh JR, Zhang X, Nagano MC . Wnt5a is a cell-extrinsic factor that supports self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. J Cell Sci 2011; 124 (Pt 14): 2357–2366.

Ikegawa S, Kumano Y, Okui K, Fujiwara T, Takahashi E, Nakamura Y . Isolation, characterization and chromosomal assignment of the human WNT7A gene. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1996; 74: 149–152.

Golestaneh N, Beauchamp E, Fallen S, Kokkinaki M, Uren A, Dym M . Wnt signaling promotes proliferation and stemness regulation of spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells. Reproduction 2009; 138: 151–162.

Wang XN, Li ZS, Ren Y, Jiang T, Wang YQ, Chen M et al. The Wilms tumor gene, Wt1, is critical for mouse spermatogenesis via regulation of sertoli cell polarity and is associated with non-obstructive azoospermia in humans. PLoS Genet 2013; 9: e1003645.

Ma P, Wang H, Guo R, Ma Q, Yu Z, Jiang Y et al. Stage-dependent Dishevelled-1 expression during mouse spermatogenesis suggests a role in regulating spermatid morphological changes. Mol Reprod Dev 2006; 73: 774–783.

Wang YK, Sporle R, Paperna T, Schughart K, Francke U . Characterization and expression pattern of the frizzled gene Fzd9, the mouse homolog of FZD9 which is deleted in Williams-Beuren syndrome. Genomics 1999; 57: 235–248.

Kimura T, Nakamura T, Murayama K, Umehara H, Yamano N, Watanabe S et al. The stabilization of beta-catenin leads to impaired primordial germ cell development via aberrant cell cycle progression. Dev Biol 2006; 300: 545–553.

Li Q, Ishikawa TO, Miyoshi H, Oshima M, Taketo MM . A targeted mutation of Nkd1 impairs mouse spermatogenesis. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 2831–2839.

Kohn MJ, Kaneko KJ, DePamphilis ML . DkkL1 (Soggy), a Dickkopf family member, localizes to the acrosome during mammalian spermatogenesis. Mol Reprod Dev 2005; 71: 516–522.

Li A, Chan B, Felix JC, Xing Y, Li M, Brody SL et al. Tissue-dependent consequences of Apc inactivation on proliferation and differentiation of ciliated cell progenitors via Wnt and notch signaling. PLoS One 2013; 8: e62215.

Bialecka M, Young T, Chuva de Sousa Lopes S, ten Berge D, Sanders A, Beck F et al. Cdx2 contributes to the expansion of the early primordial germ cell population in the mouse. Dev Biol 2012; 371: 227–234.

Aramaki S, Hayashi K, Kurimoto K, Ohta H, Yabuta Y, Iwanari H et al. A mesodermal factor, T, specifies mouse germ cell fate by directly activating germline determinants. Dev Cell 2013; 27: 516–529.

Chawengsaksophak K, Svingen T, Ng ET, Epp T, Spiller CM, Clark C et al. Loss of Wnt5a disrupts primordial germ cell migration and male sexual development in mice. Biol Reprod 2012; 86: 1–12.

Laird DJ, Altshuler-Keylin S, Kissner MD, Zhou X, Anderson KV . Ror2 enhances polarity and directional migration of primordial germ cells. PLoS Genet 2011; 7: e1002428.

Bernard P, Harley VR . Wnt4 action in gonadal development and sex determination. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39: 31–43.

Lau YF, Li Y . The human and mouse sex-determining SRY genes repress the Rspol/beta-catenin signaling. J Genet Genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 2009; 36: 193–202.

Chang H, Gao F, Guillou F, Taketo MM, Huff V, Behringer RR . Wt1 negatively regulates beta-catenin signaling during testis development. Development 2008; 135: 1875–1885.

Tanwar PS, Kaneko-Tarui T, Zhang L, Rani P, Taketo MM, Teixeira J . Constitutive WNT/beta-catenin signaling in murine Sertoli cells disrupts their differentiation and ability to support spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod 2010; 82: 422–432.

Boyer A, Yeh JR, Zhang X, Paquet M, Gaudin A, Nagano MC et al. CTNNB1 signaling in sertoli cells downregulates spermatogonial stem cell activity via WNT4. PLoS One 2012; 7: e29764.

Chang YF, Lee-Chang JS, Harris KY, Sinha-Hikim AP, Rao MK . Role of beta-catenin in post-meiotic male germ cell differentiation. PLoS One 2011; 6: e28039.

Sadate-Ngatchou PI, Payne CJ, Dearth AT, Braun RE . Cre recombinase activity specific to postnatal, premeiotic male germ cells in transgenic mice. Genesis 2008; 46: 738–742.

Rivas B, Huang Z, Agoulnik AI . Normal fertility in male mice with deletion of beta-catenin gene in germ cells. Genesis 2014; 52: 328–332.

Takase HM, Nusse R . Paracrine Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates proliferation of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the adult mouse testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: E1489–E1497.

Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R . Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem 1996; 61: 514–523.

Miller JR . The Wnts. Genome Biol 2002; 3: 1–15.

Banziger C, Soldini D, Schutt C, Zipperlen P, Hausmann G, Wntless Basler K . A conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell 2006; 125: 509–522.

Bartscherer K, Pelte N, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M . Secretion of Wnt ligands requires Evi, a conserved transmembrane protein. Cell 2006; 125: 523–533.

Belenkaya TY, Wu Y, Tang X, Zhou B, Cheng L, Sharma YV et al. The retromer complex influences Wnt secretion by recycling wntless from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. Dev Cell 2008; 14: 120–131.

Fu J, Jiang M, Mirando AJ, Yu HM, Hsu W . Reciprocal regulation of Wnt and Gpr177/mouse Wntless is required for embryonic axis formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 18598–18603.

Carpenter AC, Rao S, Wells JM, Campbell K, Lang RA . Generation of mice with a conditional null allele for Wntless. Genesis 2010; 48: 554–558.

Fu J, Ivy Yu HM, Maruyama T, Mirando AJ, Hsu W . Gpr177/mouse Wntless is essential for Wnt-mediated craniofacial and brain development. Dev Dyn 2011; 240: 365–371.

Zhu X, Zhu H, Zhang L, Huang S, Cao J, Ma G et al. Wls-mediated Wnts differentially regulate distal limb patterning and tissue morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2012; 365: 328–338.

Huang S, Zhu X, Liu Y, Tao Y, Feng G, He L et al. Wls is expressed in the epidermis and regulates embryonic hair follicle induction in mice. PLoS One 2012; 7: e45904.

Zhu X, Liu Y, Zhao P, Dai Z, Yang X, Li Y et al. Gpr177-mediated Wnt signaling is required for fungiform placode initiation. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 582–588.

Zhu X, Zhao P, Liu Y, Zhang X, Fu J, Ivy Yu HM et al. Intra-epithelial requirement of canonical Wnt signaling for tooth morphogenesis. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 12080–12089.

Yang G, Zhou J, Teng Y, Xie J, Lin J, Guo X et al. Mesenchymal TGF-beta signaling orchestrates dental epithelial stem cell homeostasis through Wnt signaling. Stem Cells 2014; 32: 2939–2948.

Wang LT, Wang SJ, Hsu SH . Functional characterization of mammalian Wntless homolog in mammalian system. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2012; 28: 355–361.

Kerr GE, Young JC, Horvay K, Abud HE, Loveland KL . Regulated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling sustains adult spermatogenesis in mice. Biol Reprod 2014; 90: 3.

Nelson WJ, Nusse R . Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science 2004; 303: 1483–1487.

Lee NP, Mruk DD, Wong CH, Cheng CY . Regulation of Sertoli-germ cell adherens junction dynamics in the testis via the nitric oxide synthase (NOS)/cGMP/protein kinase G (PRKG)/beta-catenin (CATNB) signaling pathway: an in vitro and in vivo study. Biol Reprod 2005; 73: 458–471.

Oatley JM, Oatley MJ, Avarbock MR, Tobias JW, Brinster RL . Colony stimulating factor 1 is an extrinsic stimulator of mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Development 2009; 136: 1191–1199.

Chen LY, Willis WD, Eddy EM . Targeting the Gdnf gene in peritubular myoid cells disrupts undifferentiated spermatogonial cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: 1829–1834.

DeFalco T, Potter SJ, Williams AV, Waller B, Kan MJ, Capel B . Macrophages contribute to the spermatogonial niche in the adult testis. Cell Rep 2015; 12: 1107–1119.

Aitken RJ, Smith TB, Jobling MS, Baker MA, De Iuliis GN . Oxidative stress and male reproductive health. Asian J Androl 2014; 16: 31–38.

Guerriero G, Trocchia S, Abdel-Gawad FK, Ciarcia G . Roles of reactive oxygen species in the spermatogenesis regulation. Front Endocrinol 2014; 5: 56.

Nakamura BN, Lawson G, Chan JY, Banuelos J, Cortes MM, Hoang YD et al. Knockout of the transcription factor NRF2 disrupts spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Free Radic Biol Med 2010; 49: 1368–1379.

Ishii T, Matsuki S, Iuchi Y, Okada F, Toyosaki S, Tomita Y et al. Accelerated impairment of spermatogenic cells in SOD1-knockout mice under heat stress. Free Radic Res 2005; 39: 697–705.

George SK, Jiao Y, Bishop CE, Lu B . Oxidative stress is involved in age-dependent spermatogenic damage of Immp2l mutant mice. Free Radic Biol Med 2012; 52: 2223–2233.

Morimoto H, Iwata K, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Atsuo O, Kanatsu-Shinohara M et al. ROS are required for mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 2013; 12: 774–786.

Koch S, Acebron SP, Herbst J, Hatiboglu G, Niehrs C . Post-transcriptional Wnt signaling governs epididymal sperm maturation. Cell 2015; 163: 1225–1236.

Zi Z, Zhang Z, Li Q, An W, Zeng L, Gao D et al. CCNYL1, but not CCNY, cooperates with CDK16 to regulate spermatogenesis in mouse. PLoS Genet 2015; 11: e1005485.

Gallardo T, Shirley L, John GB, Castrillon DH . Generation of a germ cell-specific mouse transgenic Cre line, Vasa-Cre. Genesis 2007; 45: 413–417.

Holdcraft RW, Braun RE . Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development 2004; 131: 459–467.

Chen SR, Tang JX, Cheng JM, Li J, Jin C, Li XY et al. Loss of Gata4 in Sertoli cells impairs the spermatogonial stem cell niche and causes germ cell exhaustion by attenuating chemokine signaling. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 37012–37027.

Li XX, Chen SR, Shen B, Yang JL, Ji SY, Wen Q et al. The heat-induced reversible change in the blood-testis barrier (BTB) is regulated by the androgen receptor (AR) via the partitioning-defective protein (Par) polarity complex in the mouse. Biol Reprod 2013; 89: 1–10.

Chang YF, Lee-Chang JS, Panneerdoss S, MacLean JA, Rao MK . Isolation of Sertoli, Leydig, and spermatogenic cells from the mouse testis. Biotechniques 2011; 51: 344.

Boucheron C, Baxendale V . Isolation and purification of murine male germ cells. Methods Mol Biol 2012; 825: 59–66.

Chen SR, Zheng QS, Zhang Y, Gao F, Liu YX . Disruption of genital ridge development causes aberrant primordial germ cell proliferation but does not affect their directional migration. BMC Biol 2013; 11: 22.

Mahfouz R, Sharma R, Lackner J, Aziz N, Agarwal A . Evaluation of chemiluminescence and flow cytometry as tools in assessing production of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion in human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril 2009; 92: 819–827.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Yang Xiao (State Key Laboratory of Proteomics, Genetic Laboratory of Development and Diseases, Institute of Biotechnology, AMMS, Beijing, China) for her generous donation of Gpr177+/flox mice. We also thank Dr. Chen Qi from School of Medicine, University of Nevada for providing AQP3 antibody. This work was supported by Major Research Plan '973' Project (2011CB944302 and 2012CB944702), National Technology Support Project (2012DAI131B08) and Natural Science Foundation of China (31171380, 31471352, 31501198 and 81270662).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by M Agostini

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website

Rights and permissions

Cell Death and Disease is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, SR., Tang, JX., Cheng, JM. et al. Does murine spermatogenesis require WNT signalling? A lesson from Gpr177 conditional knockout mouse models. Cell Death Dis 7, e2281 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2016.191

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2016.191

This article is cited by

-

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of sperm miRNAs identifies hsa-miR-9-3p, hsa-miR-30b-5p and hsa-miR-122-5p as potential biomarkers of male infertility and sperm quality

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2022)

-

A miR-125b/CSF1-CX3CL1/tumor-associated macrophage recruitment axis controls testicular germ cell tumor growth

Cell Death & Disease (2018)

-

Role of WNT signaling in epididymal sperm maturation

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2018)