Abstract

RhoA GTPase dysregulation is frequently reported in various tumours and haematologic malignancies. RhoA, regulating Rho-associated coiled-coil-forming kinase 1 (ROCK1), modulates multiple cell functions, including malignant transformation, metastasis and cell death. Therefore, RhoA/ROCK1 could be an ideal candidate target in cancer treatment. However, the roles of RhoA/ROCK1 axis in apoptosis of leukaemia cells remain elusive. In this study, we explored the effects of RhoA/ROCK1 cascade on selenite-induced apoptosis of leukaemia cells and the underlying mechanism. We found selenite deactivated RhoA/ROCK1 and decreased the association between RhoA and ROCK1 in leukaemia NB4 and Jurkat cells. The inhibited RhoA/ROCK1 signalling enhanced the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 in a Mek1/2-independent manner. Erk1/2 promoted apoptosis of leukaemia cells after it was activated. Intriguingly, it was shown that both RhoA and ROCK1 were present in the multimolecular complex containing Erk1/2. GST pull-down analysis showed ROCK1 had a direct interaction with GST-Erk2. In addition, selenite-induced apoptosis in an NB4 xenograft model was also found to be associated with the RhoA/ROCK1/Erk1/2 pathway. Our data demonstrate that the RhoA/ROCK1 signalling pathway has important roles in the determination of cell fates and the modulation of Erk1/2 activity at the Mek–Erk interplay level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) is characterised by differentiation arrest at promyelocytic stage and augmentation of haematopoietic stem cells.1 Owing to the abnormal aggregation of immature precursors and the repression of normal haemopoiesis, APL presents as a medical emergency, with a high rate of early fatalities from haemorrhaging.2 Although all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) has been shown to be effective in APL therapy, the relapse still occurs in 20% of patients because of an elevation in white blood cell count induced by ATRA treatment.3 In this context, targeting mutant or hyperactivated molecules to elicit specific apoptosis of leukaemia cells would be a rational approach for more efficacious therapy and may even result in complete remission.

RhoA, the prototype protein of Rho GTPases superfamily, cycles from a GDP-bound inactive state to a GTP-bound active state.4 RhoA is involved in a variety of cellular functions, including cytoskeleton organisation, cell cycle, cell survival, cell polarity and cell migration. Once activated, RhoA transmits signals to pleiotropic effectors by binding to its immediate downstream target, Rho-associated coiled-coil-forming kinase 1 (ROCK1). From an autoinhibited form, ROCK1 is activated when its C-terminal region binds to RhoA.5 Upregulation of RhoA and ROCK1 has been well documented in tumours and are related to cancer progression, metastasis and poor prognosis.6, 7 Perturbations in the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway have been reported in leukaemia cells as well.8 Thus, the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway may be a promising target for cancer therapy. Indeed, inhibition of RhoA/ROCK1 pathway leads to tumour cell death and reduced metastasis.9, 10 Although growing investigations have shown that the RhoA/ROCK module interacts with various signalling molecules to affect apoptosis in solid tumours, little is known about the roles of this signalling pathway in leukaemia cell survival and death. A better understanding of RhoA/ROCK1 regulation on leukaemia cells could be contributing to develop new modalities for treating haematologic malignancies.

In this study, we investigated the modulation of the RhoA/ROCK1 axis on leukaemia cell fates and explored the potential underlying mechanism. We demonstrated that inhibition of the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway increased the susceptibility of NB4 and Jurkat cells to the cytotoxic compound selenite. The ablated RhoA/ROCK1 signalling led to the reinforced activation of Erk1/2. Moreover, the enhanced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 promoted programmed cell death. Interestingly, the physical interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 was involved in the interplay between RhoA/ROCK1 signalling and Erk1/2. These results indicate that targeting RhoA/ROCK1 axis could be an optional therapeutic strategy for leukaemia.

Results

Selenite treatment inhibited RhoA/ROCK1 axis in leukaemia cells

Our previous studies have shown that sodium selenite induces apoptosis in malignant cells.11, 12 To further elucidate the underlying mechanisms, we examined the effects of selenite on leukaemic cells and normal monocytes. As shown in Figure 1a, 20 μM of selenite induced the apoptosis of leukaemia cell lines NB4 and Jurkat in a time-dependent manner, which is consistent with our previous reports.12 Immunoblot analysis showed the increased cleavages of caspase 9 and caspase 3, especially at 18 h after selenite treatment. Annexin V/PI staining showed apoptosis occurred in about 40% and 37% of NB4 and Jurkat cells at 18 h, respectively. Conversely, selenite failed to cause apoptotic death in normal blood cells (Supplementary Figure S1a).

Selenite-induced apoptosis and inhibition of the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway. (a) NB4 and Jurkat cells were treated with selenite (20 μM). Upper, the cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 were visualised by immunoblotting at various time points as indicated. Lower, apoptosis ratio was determined using an Annexin V/PI staining kit. (b) At different time points after selenite treatment, the expressions and activities of RhoA and ROCK1 were determined by immunoblot analysis. RhoA-GTP was evaluated using Rhotekin RBD-GST pull-down as described in the Materials and Methods, and GST proteins were probed to confirm equal loading. (c) Effects of selenite on the association of RhoA and ROCK1. Cells were treated with selenite for 6 and 18 h. Antibodies against RhoA and ROCK1 were used to precipitate proteins from cell lysates, and bound proteins were probed. β-Actin in whole-cell lysate (WCL) was probed to confirm equal loading. (d) Immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells treated with selenite or PBS for 18 h were fixed, and RhoA (green) and ROCK1 (red) were stained with primary antibodies, followed by staining with secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC or Cy3. The nucleus was labelled with DAPI. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope. The statistical graphs are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments; *P<0.05. Scale bar, 10 μm

Next, we evaluated the effects of selenite on RhoA and ROCK1 in leukaemia cells. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the activation of RhoA (shown as RhoA-GTP) was reduced robustly at 6 h and was maintained at low levels through 6–18 h (Figure 1b). Consistently, the phosphorylated level of myosin phosphatase (MYPT1) was significantly inhibited at 6 h by selenite and that decreased level was maintained (Figure 1b). As a well-established substrate of ROCK1,13 phosphorylation of MYPT1 is associated with the activity of ROCK1. This result indicated ROCK1, the direct substrate of RhoA, also was probably inhibited by selenite. As the binding with activated RhoA is believed to keep ROCK1 activation,5 we performed Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and immunofluorescence analysis to check whether the selenite-induced inactivation of RhoA is related to ROCK1 downregulation. Co-IP assay showed the association between RhoA and ROCK1 was robustly interfered since 6 h (Figure 1c), in consistent with the changes of RhoA and ROCK1 activities. Moreover, the immunofluorescence assay revealed that ROCK1 predominantly co-localised with RhoA in untreated cells (Figure 1d). But this co-location was smeared after selenite treatment (Figure 1d), supporting the finding that the molecular binding of RhoA to ROCK1 declined. These results together indicate that selenite inhibits the activation of RhoA, decreases the association of RhoA with ROCK1, and thereafter deactivates ROCK1.

RhoA modulated cell apoptosis via ROCK1

The RhoA/ROCK1 pathway is reported to be involved in the modulation of cell survival.14, 15 As shown above, RhoA/ROCK1 axis was inhibited by selenite in leukaemia cells undergoing apoptosis, whereas this axis was little affected in normal counterparts that remained intact (Supplementary Figures S1a and S1b). Thus, we tested whether the RhoA/ROCK1 axis regulates the fate of leukaemia cells after selenite treatment. Leukaemia cells were pre-treated with RhoA inhibitor, C3 transferase, or ROCK1 inhibitor, Y27632. Both inhibitors efficiently blocked their corresponding signalling, as demonstrated by immunoblotting of RhoA-GTP and phosphorylated MYPT1 (Supplementary Figures S2a and S2b). Leukaemia cells treated with C3 transferase or Y27632 showed significantly increased apoptosis following 18 h of selenite treatment (Figure 2a). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated the expression levels of cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 were enhanced when RhoA or ROCK1 were inhibited (Supplementary Figures S2a and S2b), indicating that RhoA and ROCK1 negatively regulates apoptosis. Additionally, RhoA inhibition led to the deactivation of ROCK1 (Supplementary Figure S2a), supported our aforementioned finding that RhoA acts upstream of ROCK1. Subsequently, siRNA knockdown experiments were performed to validate the roles of RhoA and ROCK1 in cell apoptosis. Decreased expressions of RhoA or ROCK1 were achieved with different siRNAs (siRhoA-1 and siRhoA-2 for RhoA knockdown; siROCK1-1 and siROCK1-2 for ROCK1 knockdown) (Supplementary Figures S2c and S2d). Similar to the effects of specific inhibitors, siRNAs targeting RhoA or ROCK1 upregulated the populations of apoptotic cells and the accumulations of apoptosis-related proteins, including cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 (Figure 2b; Supplementary Figures S2c and S2d). These observations demonstrated both RhoA and ROCK1 have important roles in apoptosis. However, it is uncertain whether RhoA employs ROCK1 to exert effects on cell death. To answer this question, we ectopically expressed the myc-tagged constitutively-active RhoA plasmids (RhoA L63-myc) alone or in combination with Y27632 treatment in leukaemia cells. As expected, the expression of RhoA L63-myc enhanced ROCK1 activation and decreased selenite-induced apoptosis (Supplementary Figure S2e; Figure 2c). However, these effects were completely reversed by ROCK1 inhibitor. As shown in Figure 2c and Supplementary Figure S2e, selenite-induced apoptosis was remarkably enhanced by combinational use of Y27632 in cells expressing constitutively-active RhoA. In comparison with vehicle-treated cells, Y27632 treatment in cells expressing RhoA L63 led to additional cell death and enhanced cleavage of caspase 9 and caspase 3 (Figure 2c; Supplementary Figure S2e). This result indicated that ROCK1 is indispensible for RhoA to exert its modulatory effects on cell apoptosis. In summary, the suppression of RhoA/ROCK1 cascade results in apoptosis in leukaemia cells, and ROCK1 acts as the direct effector of RhoA in cell death progression.

RhoA/ROCK1 cascade was implicated in apoptotic regulation. (a) Apoptotic rates of cells were assessed using Annexin V/PI staining. NB4 and Jurkat cells pre-treated with C3 transferase (4 μg/ml) and Y27632 (20 μM) were incubated with selenite for 18 h, and cells were then stained and analysed using a flow cytometer. (b) Ratio of apoptosis in RhoA- or ROCK1-silenced cells. Cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting RhoA (siRhoA-1 and siRhoA-2) or ROCK1 (siROCK1-1 and siROCK1-2) for 24 h, then exposed to selenite for another 18 h, and apoptosis was determined with flow cytometry analysis. (c) Twenty-four hours after constitutively active RhoA L63-myc plasmid was transfected into cells, Y27632 (20 μM) were added into one group of cells, then all three groups of cells were treated with selenite for 18 h. Apoptotic cells were quantified using a flow cytometer. Cells in the vehicle group were treated with the same procedures except for plasmids and siRNAs. The data are presented as mean±S.D. of three independent experiments; *P<0.05

RhoA/ROCK1 negatively regulated Erk1/2 activity

Erk1/2 has important roles in selenite-induced apoptosis.16, 17 Given that the RhoA/ROCK1 signal pathway is engaged in the regulation of Erk1/2 activity,18, 19 we monitored the interaction between RhoA/ROCK1 and Erk1/2 in selenite-induced apoptosis. Firstly, we checked the changes of Erk1/2. Time-cause analysis showed Erk1/2 was dynamically activated by selenite treatment and the peak activation was observed at 6 h (Figure 3a). Nevertheless, the expression of total Erk1/2 protein was not altered after selenite treatment. In the next, experiments were performed to illuminate the relationship between RhoA/ROCK1 and Erk1/2. As shown in Figure 3b and Supplementary Figure S3a, the selenite-induced stimulation of Erk1/2, especially in the first 6 h, was markedly enhanced when RhoA was attenuated by an inhibitor treatment or siRNA transfection. Unexpectedly, the activity of upstream Mek1/2 was not affected. Similarly, the inactivation of ROCK1 enhanced selenite-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 at early stage, but did not change the level of phospho-Mek1/2 (Figure 3c; Supplementary Figure S3b). These results suggested RhoA and ROCK1 negatively affect the activation of Erk1/2. We further checked the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 in cells transfected with RhoA L63-myc plasmid. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the amount of phosho-Erk1/2 in cells expressing constitutively-activated RhoA was obviously decreased compared with control cells at 0 h and 6 h (Figure 3d; Supplementary Figure S3c). However, this suppression was reversed by Y27632 treatment before selenite dosing. In cells expressing constitutively-activated RhoA, the inhibition of ROCK1 induced an increase in Erk1/2 phosphorylation that was even stronger than that in control cells (Figure 3d; Supplementary Figure S3c). Impressively, the selenite-induced activation of Mek1/2 remained unaffected in these assays (Figure 3d). Taken together, it suggests ROCK1 mediates the negative regulation of RhoA/ROCK1 signalling on the activity of Erk1/2.

RhoA/ROCK1 axis negatively regulated the activity of Erk1/2. (a) Selenite induced kinetic changes in Erk1/2 activation. Cells treated with selenite for various time periods were lysed, and immunoblotted for Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), Mek1/2 and phospho-Mek1/2 (Ser217/221). (b–d) Immunoblot indicating the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and Mek1/2. (b) Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting RhoA for 24 h or pre-treated with C3 transferase (4 μg/ml), then treated with selenite. The targeted proteins were detected with corresponding antibodies at indicated time points. (c) Cells transfected with siRNA targeting ROCK1 for 24 h or pre-treated with Y27632 (20 μM) were treated with selenite. The expressions of targeted proteins were determined using corresponding antibodies at indicated time points. (d) Cells were transfected with constitutively-active RhoA plasmid for 24 h in the presence or absence of Y27632 (20 μM), and then were treated with selenite. Proteins were immunoblotted in cell lysates using indicated antibodies

RhoA regulated the physical interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2

Generally, the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 is in concert with the activation of Mek1/2. However, we found the activation of Mek1/2 was little affected, whereas RhoA/ROCK1 axis induced apparent changes of Erk1/2 activities. Jimenez-Sainz et al.20 reported an independent stimulation of Erk1/2 was resulted from the specific association of Mek1/2 with regulatory proteins. Considering the similarity that Erk1/2 was separately regulated, we performed Co-IP experiments to test whether RhoA/ROCK1 bind to Mek1/2. Unexpectedly, endogenous ROCK1 was not found in complex with Mek1/2 (Supplementary Figure S4b). Hoever, an association was identified between Erk1/2 and ROCK1, which was decreased after selenite incubation (Supplementary Figure S4a). Consistently, the immunofluorescence data showed the signal of ROCK1 was overlapped with that of Erk1/2 and selenite interfered with the co-localisation between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 (Figure 4a). To further consolidate the interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2, leukaemia cells were transfected with wild-type Erk2 (Erk2-HA) plasmid. As shown in Figure 4b, both the Erk2-HA and endogenous Erk2 achieved maximal phosphorylation at 6 h post selenite treatment. Meanwhile, the association between ROCK1 and Erk2-HA was tremendously hampered by selenite at 6 h and remained at low levels (Figure 4b). In addition, RhoA was located in the complex containing ROCK1 and Erk2-HA as well (Figure 4b). This co-existence was also observed at the endogenous level (Supplementary Figure S4a). Similar to ROCK1, RhoA showed a decreased combination with Erk2-HA or endogenous Erk1/2 in selenite-treated cells. These observations suggest that Erk1/2 probably has a physical association with RhoA and/or ROCK1. To determine whether there is a direct association between those proteins, Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay was performed. Saturating amounts of GST-fused Erk2 were incubated with cell lysates, and the precipitated endogenous proteins were identified. As shown in Figure 4c, only ROCK1, but not RhoA, had an interaction with GST-Erk2, and this interaction was challenged by selenite treatment as the activity of ROCK1 was decreased. This observation illuminates that ROCK1 is directly associated with Erk1/2 and this interaction probably depends on the activity of ROCK1.

RhoA regulated the interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2. (a) Immunofluorescence staining. Erk1/2 (red) and ROCK1 (green) were stained with primary antibodies in selenite-treated or untreated cells, followed by staining with secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC or Cy3. The nucleus was labelled with DAPI. (b) Co-IP of ROCK1 and Erk2-HA. Cells were transfected with wild-type Erk2-HA plasmids and treated with selenite for different time points. Then cells lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-ROCK1 and anti-HA antibodies, after which RhoA, ROCK1 and Erk2-HA in the immunoprecipitated products were detected by immunoblot. The expression of phosphorylated MYPT1 and Erk2-HA in WCL were probed using antibodies against phospho-MYPT1 (Thr853) and phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), respectively, and β-actin in WCL were probed to confirm equal loading. (c) ROCK1 associated with Erk2 in vitro. GST-Erk2 fusion proteins (2 μg) were incubated with cell lysates in the presence of GSH beads, and the immobilised ROCK1 and GST-Erk2 were probed. The expressions of phospho-MYPT1 and β-actin in WCL were also determined using immunoblot. (d) Cells were transfected with 2, 4 or 8 μg of RhoA-myc L63 plasmids and 4 μg of Erk2-HA, and extracts were precipitated with antibodies against ROCK1 or HA. The eluted proteins or whole-cell lysates were analysed using immunoblot. (e) Co-IP of ROCK1 and Erk2-HA. Cells were transfected with RhoA L63-myc plasmids or pre-treated with C3 transferase, and then treated with selenite for 6 h. The antibodies against ROCK1 and HA were used to precipitate proteins from cell lysates, and bound proteins were probed. The expressions of phospho-MYPT1 and phospho-Erk2-HA were detected using immunoblot. β-actin was probed to confirm equal loading. Black arrow indicates phospho-Erk2-HA. As the phosphorylation of Erk2-HA was detected using the antibody against phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), the bands of phospho-Erk2 (about 43 kDa) were also developed

RhoA directly regulates the activity of ROCK1 as we described above, and is physically proximal to Erk1/2. Therefore, we inferred that RhoA probably modulates the interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2. To confirm this hypothesis, cells were transfected with various amounts of RhoA L63 plasmids and a fixed amount of Erk2-HA, then the association between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 was determined using Co-IP test. We found that the activity of ROCK1 was increased when its association with RhoA was enhanced (Figure 4d). More importantly, the association between ROCK1 and Erk2-HA was elevated as ROCK1 was upregulated (Figure 4d), suggesting that the binding with Erk1/2 is dependent on ROCK1. Meanwhile, the phosphorylated level of Erk2-HA was decreased correspondingly, indicating that the physical association between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 probably regulates the activity of Erk1/2. Indeed, we found selenite-induced activation of Erk2-HA was inhibited when the association of ROCK1 with Erk2-HA was enhanced in cells (Figure 4e), where ROCK1 was upregulated by constitutively-active RhoA expression. Conversely, the phosphorylation of Erk2-HA was increased while the association between ROCK1 and Erk2-HA was attenuated by RhoA inhibitor treatment (Figure 4e). These results together illustrate that the association between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 negatively regulates the activation of Erk1/2 and RhoA modulates this physical binding.

Erk1/2 acted downstream of RhoA/ROCK1 in selenite-induced apoptosis

Initially, leukaemia cells were treated with Erk1/2 antagonist, PD98059, before selenite dosing. Immunoblot assay revealed that the accumulations of cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 were substantially reduced in PD98059-treated cells (Figure 5a). An apparent decline in apoptotic populations was observed in PD98059-treated cells as well (Figure 5a). This result indicated that Erk1/2 positively regulates the selenite-induced apoptosis. Thereafter, we examined whether Erk1/2 is the downstream module of RhoA/ROCK1 signalling during apoptosis regulation. As shown in Figure 5b, ROCK1 inhibition enhanced selenite-induced apoptosis. Compared with Y27632-treated cells, the co-incubation of Y27632 and PD98059 led to a reduction in apoptosis, manifested as declined apoptotic populations and reduced accumulations of apoptosis-related proteins (Figure 5b). This result indicates that Erk1/2 is a pivotal downstream effector of RhoA/ROCK1 axis in selenite-induced apoptotic death.

Erk1/2 was indispensible for apoptosis induction. (a) Cells were pre-treated with Erk1/2 inhibitor, PD98059 (20 μM), and then exposed to selenite for 6 h or 18 h. Upper, expressions of phospho-Erk1/2, cleaved caspase-9, and cleaved caspase-3 were investigated using immunoblot; lower, apoptotic cells were detected using a flow cytometry. (b) Cells were treated with Y27629 (20 μM) alone or with PD98059 (20 μM) before selenite dosing. Upper, cell lysates were subject to immunoblot assay; lower, proportion of apoptotic cells was determined by Annexin V/PI staining. * indicates P<0.05

RhoA/ROCK1/Erk1/2 signalling was involved in selenite-induced apoptosis in vivo

We next investigated the effects of selenite on tumour growth of leukaemia cells in vivo. It was shown that tumour growth was markedly suppressed 28 days after implantation in selenite-injected mice (Figure 6a). TUNEL staining showed that selenite induced obvious DNA fragmentations in xenografts (Figure 6b). To further certificate the apoptotic mechanism found in vitro, the proteins of interest were examined for expressions and activations. Immunoblots of tumour tissues demonstrated that the expressions of RhoA, ROCK1 and phospho-MYPT1 were impaired, whereas Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2, cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3 were upregulated in selenite-injected mice (Figure 6c). In addition, immunohistochemistry assay confirmed the changes of key components, including RhoA, ROCK1, phospho-Erk1/2 and cleaved caspase-3, were similar to those observed in leukaemia cell lines in vitro (Figure 6d). These findings imply that the selenite-induced apoptosis in vivo is associated with the inhibition of RhoA/ROCK1 and activation of Erk1/2.

Selenite demonstrated antitumor activity and induced apoptosis in xenograft animal model. Fourteen days after NB4 cells inoculation, nude mice (6 mice per group) were injected with PBS or selenite (3 mg/kg, every 2 d, i.p.). (a) Tumour volumes were calculated at the indicated intervals. Data are presented as means±S.D. (b) Representative images of in situ labelling of apoptotic cells using TUNEL assay. Tumours obtained from animals 32 days after selenite exposure were fixed, and stained to detect apoptosis using a TUNEL staining kit. (c) Pooled tumour tissues were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis. (d) Fixed tumour samples were subjected to immunohistochemistry assay using indicated antibodies. Representative images from PBS- and selenite-treated samples are shown *P<0.05. Scale bar, 100 μm

Discussion

Previous reports have suggested the importance of RhoA/ROCK1 axis in cell survival. Tsai and Wei10 reported that the activated RhoA and ROCK1 prevented cell death in a heat shock-triggered stress model. Li et al21 reported that the inactivation of RhoA/ROCK1 by chemical antagonists caused dose-dependent cell death. In consistent with those reports, we observed that the survival of normal monocytes was not affected by selenite while the RhoA/ROCK1 axis was not downregulated. However, malignant cells underwent apoptotic cell death when RhoA/ROCK signalling was wrecked in leukaemia cells and xenograft models, indicating the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway has key roles in the fate determination of haematologic cells. Together with other 22 Rho GTPases, RhoA contributes to multifaceted functions of blood cells in various physiologic processes and pathologic states.22, 23 The roles of RhoA in haematologic malignancies have attracted great interests, although it is less studied. Multiple haematological disorder-associated oncoproteins, including KIT, FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) and BCR-ABL, are reported to overactive RhoA/ROCK1 pathway.24, 25 Deactivating this pathway interferes in the proliferation and transformation of progenitor cells.25, 26 Moreover, studies on primary leukaemia cells have confirmed that the inhibition of RhoA/ROCK1 signalling promotes cell death.26, 27, 28 These reports indicate that the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway is a potential target for leukaemia therapy. In this study, we demonstrated that the RhoA/ROCK1 signalling was implicated in apoptosis of APL and ATL cells resulted from chemical toxin assaults. When selenite was added into leukaemia cells, RhoA/ROCK1 cascade was inhibited, which eventually led to the programmed cell death. More importantly, when this pathway was further inhibited, the selenite-induced apoptosis was aggravated. These results support our notion that the RhoA/ROCK1 pathway has key roles in the survival of malignant cells, and it is an ideal target for leukaemia therapy.

Although the RhoA/ROCK1 module has been proved to determine cell fates, the mechanism by which it exerts effects on apoptosis is largely unknown. Here, we found that Erk1/2 was employed by RhoA/ROCK1 in apoptosis induction. Many substrates of ROCK1 have been identified, including MYPT, ERM family and LIMK.29 MAPKs, such as Akt and JNK, have also been reported to be regulated by RhoA/ROCK1 axis.29, 30 Another MAPK, Erk1/2, was also reported to be regulated by RhoA and ROCK1.31, 32 However, this modulation is usually indirect. Gallagher et al.33 reported that MEKK1, which phosphorylated Mek to modulate the activity of Erk1/2, was regulated by RhoA. In another study, the RhoA/ROCK1 module was found to regulate the very upstream component of the Mek/Erk pathway.34 Unexpectedly, we found RhoA/ROCK1 cascade directly regulated the phosphorylation of Erk1/2. Without altering the phosphorylated level of Mek1/2, RhoA and ROCK1 negatively regulated the activity of Erk1/2. Owing to the remarkable change of RhoA/ROCK1 activity at early stage after selenite treatment, the activity of Erk1/2 was dominantly influenced by this signal during first 6 h. Furthermore, we observed a direct association between ROCK1 and Erk1/2. This finding is supported by a study from von Kriegsheim and co-workers.35 They observed the combination of ROCK1 with Erk1/2 in neuron cells as well. Moreover, we found there were two conserved Erk1/2 docking motifs, which are recognised by a common docking domain in Erk1/2, in the primary sequence of ROCK1 by using a computational approach (Data not show). It is tempting to believe that ROCK1 has a direct interaction with Erk1/2.

This direct interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 depends on the intensity of RhoA/ROCK1 signalling. When ROCK1 was downregulated, the binding became weakened and the activity of Erk1/2 was increased. Conversely, the upregulation of ROCK1 increased the physical connection and enhanced the Erk1/2 activation. Therefore, we speculate that the ROCK1-mediated Erk1/2 regulation takes place at the Mek–Erk interface and probably depends on the molecular binding. Jimenez-Sainz et al.20 reported a similar result that the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 was changed, whereas Mek1/2 activation stayed intact. They suggested this regulation was related to the subcellular localizations of MAPK cascade components. The spatial regulation of Mek1/2 and Erk1/2 is crucial for Erk1/2 activation. In this study, we observed that RhoA was presented in the ROCK1-Erk1/2 complex as well. Moreover, this association with Erk1/2 was positively related to the activity of RhoA (Figures 4b and d). Consistently, endogenous RhoA and Erk1/2 were observed to be physically proximal when RhoA was activated (Supplementary Figure S4a). Once activated, RhoA is shuttled to the cell membrane.36, 37 Indeed, we observed the membrane localisation of RhoA was more obvious in unstimulated cells (Figure 1d). Therefore, this interaction with activated RhoA probably locates Erk1/2 proximally to the cellular membrane. The immunofluorescence analysis of Erk1/2 distribution supported this notion (Supplementary Figure S4c). Erk1/2 was located near the plasma membrane in unstimulated cells but in the cytoplasm after selenite treatment. Although occasionally translocating into the nucleus,38 the activated Mek1/2 is exclusively located in the cytoplasm where it phosphorylates Erk1/2.39 Herein, we infer that active RhoA specifically targets Erk1/2 to membrane away from the activated Mek1/2 via ROCK1, resulting in the independent regulation of Erk1/2 phosphorylation when RhoA is inhibited. But the exact mechanism by which RhoA/ROCK1 regulates the activation of Erk1/2 still needs to be carefully examined.

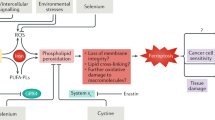

In summary, we have demonstrated a negative correlation between RhoA/ROCK1 signalling and Erk1/2 activity in human leukaemia cells. As shown in Figure 7, the activated RhoA/ROCK1 cascade directly suppresses the activation of Erk1/2. When RhoA/ROCK1 signal is downregulated by selenite, Erk1/2 is hyperactivated in a Mek-independent manner and induces apoptosis. The ROCK1 inhibitor has been found to enhance leukaemia cells apoptosis,26 when combined with clinical drugs. In this context, it would help to develop more effective therapy regimens of leukaemia to elucidate the detailed mechanism of RhoA/ROCK1 signalling-induced apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

APL NB4 cell line and acute T-cell leukaemia-derived Jurkat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against RhoA, Erk1/2, phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-Mek1/2 (Ser217/221), Mek1/2, phospho-MYPT1 (Thr853), cleaved caspase-9, cleaved caspase-3, HA-tag and myc-tag were purchased from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The antibody against ROCK1 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-β-actin and anti-GST antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Y27632 and PD98059 were purchased from Calbiochem (Darmastadt, Germany). The C3 transferase was purchased from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO, USA). Sodium selenite was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Immunoblot, immunoprecipitation and pull-down

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation were carried out according to the previously published procedures.12 For the GST pull-down test, cells were lysed, and the protein concentrations were adjusted to 2 μg/μl. Then, 2 μg of GST-Erk2 fusion proteins (Merck Millipore, MA, USA) and 40 μl of glutathione agarose beads (Sigma- Aldrich) were incubated with 200 μl of lysates for 4 h at 4 °C. The beads were separated by centrifugation at 500 × g for 2 min at 4 °C and washed three times with RIPA buffer. Bound proteins were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

siRNA, plasmid and transfection

Small interfering RNAs were synthesised by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) as previously reported (Supplementary Table 1). pRK5-myc RhoA L63 and pcDNA3-HA-ERK2 WT, which were shared at www.Addgen.org, were constructed by Nobes et al.40 and Shin et al.,41 respectively. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RhoA activation assay

RhoA activity was determined using Rhotekin RBD beads. Briefly, 200 μg of clear-cell lysates was incubated with GST-Rho binding domain (RBD) proteins immobilised on glutathione-sepharose beads for 2 h at 4 °C, centrifuged and washed. The active RhoA bound to Rhotekin RBD beads was eluted in SDS loading buffer. The eluted samples were subjected to immunoblot and analysed with antibodies against RhoA and GST.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were washed, fixed on glass slides and stained with primary antibodies, followed by staining with secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC or CY3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, PA, USA). Stained cells were observed using an Olympus laser scanning confocal FV1000 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and acquired images were analysed using Olympus Fluoview software (Tokyo, Japan).

Cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected using an Alexa Fluor 488 Annexin V/Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Invitrogen). Cells (∼2 × 105) were centrifuged, washed and incubated with 2 μl of Annexin V and 0.1 μl of propidium iodide (1 mg/ml) in 200 μl Annexin binding buffer (pH 7.4, 10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM CaCl2). The stained cells were analysed with a flow cytometer.

In vivo study

Twelve of male nu/nu mice (5 weeks old) were subcutaneously injected with NB4 cells (5 × 106). After 14 days, when the tumours were visible, the mice were randomly divided into two groups (6 mice per group). The control group received vehicle (PBS) injection i.p., and the treatment group was administered selenite i.p. every 2 days at a dose of 3 mg/kg. Eighteen days later, mice were sacrificed, tumours were excised and measured, and tissues were fixed in 10% formalin. After embedding in paraffin, DNA fragmentation in situ, which is an indicator of apoptosis, was visualised with TUNEL staining (FragEL DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit, Calbiochem).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumour tissues from mice were subjected to IHC to detect the expression or phosphorylation of proteins of interest. IHC tests were performed as the procedures previously described.42 Briefly, tumour tissues were isolated from control or selenite-treated mice and embedded in paraffin. Four-micron tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and washed in PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was achieved by incubating the sections in 0.01 M citrate (pH6.0) for 20 min at 95 °C. Following incubation with 10% goat serum for 30 min, sections were incubated with anti-RhoA, ROCK1, Erk1/2, phosphor-Erk1/2 and cleaved caspase-3 antibodies at room temperature for 60 min. Subsequently, sections were incubated with mouse/rabbit-labelled polymer from mouse EnVision kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 min at room temperature, and signal was detected using diaminobenzidine staining (Dako). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin and mounted.

Statistical analyses

The SPSS programme (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all of the statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. The data are presented as the mean±S.D., and the results were considered significantly different at a P<0.05.

Abbreviations

- APL:

-

acute promyelocytic leukaemia

- ATL:

-

acute T-cell leukaemia

- ATRA:

-

all-trans-retinoic acid

- Bcr-ABL:

-

breakpoint-cluster region (bcr) and the Abelson leukaemia (c-abl) fusion protein

- DAPI:

-

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ERM:

-

ezrin-radixin-moesin

- Erk1/2:

-

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2

- FLT3:

-

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3

- GST:

-

glutathione S-transferase

- IHC:

-

immunohistochemistry

- JNK:

-

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- LIMK:

-

LIM domain kinase

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mek1/2:

-

MAPK/Erk kinase 1 and 2

- MYPT1:

-

the targeting/regulatory subunit 1 of myosin phosphatase

- RhoA:

-

Ras homologue gene family member A

- ROCK1:

-

Rho-associated protein kinase 1

References

Lanotte M, Martin-Thouvenin V, Najman S, Balerini P, Valensi F, Berger R . NB4, a maturation inducible cell line with t(15;17) marker isolated from a human acute promyelocytic leukemia (M3). Blood 1991; 77: 1080–1086.

Kamimura T, Miyamoto T, Harada M, Akashi K . Advances in therapies for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 1929–1937.

Ferrara F . Acute promyelocytic leukemia: what are the treatment options? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010; 11: 587–596.

Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ . Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 690–701.

Jacobs M, Hayakawa K, Swenson L, Bellon S, Fleming M, Taslimi P et al. The structure of dimeric ROCK I reveals the mechanism for ligand selectivity. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 260–268.

Karlsson R, Pedersen ED, Wang Z, Brakebusch C . Rho GTPase function in tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1796: 91–98.

Lochhead PA, Wickman G, Mezna M, Olson MF . Activating ROCK1 somatic mutations in human cancer. Oncogene 2010; 29: 2591–2598.

Kuzelova K, Hrkal Z . Rho-signaling pathways in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 2008; 8: 261–267.

Marie PJ, Fromigue O, Hay E, Modrowski D, Bouvet S, Jacquel A et al. RhoA GTPase inactivation by statins induces osteosarcoma cell apoptosis by inhibiting p42/p44-MAPKs-Bcl-2 signaling independently of BMP-2 and cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1845–1856.

Tsai NP, Wei LN . RhoA/ROCK1 signaling regulates stress granule formation and apoptosis. Cell Signal 2010; 22: 668–675.

Huang F, Nie C, Yang Y, Yue W, Ren Y, Shang Y et al. Selenite induces redox-dependent Bax activation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2009; 46: 1186–1196.

Jiang Q, Wang Y, Li T, Shi K, Li Z, Ma Y et al. Heat shock protein 90-mediated inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB switches autophagy to apoptosis through becn1 transcriptional inhibition in selenite-induced NB4 cells. Mol Biol Cell 2011; 22: 1167–1180.

Shichi D, Arimura T, Ishikawa T, Kimura A . Heart-specific small subunit of myosin light chain phosphatase activates rho-associated kinase and regulates phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase target subunit 1. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 33680–33690.

Moore M, Marroquin BA, Gugliotta W, Tse R, White SR . Rho kinase inhibition initiates apoptosis in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004; 30: 379–387.

Yoshida T, Clark MF, Stern PH . The small GTPase RhoA is crucial for MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cell survival. J Cell Biochem 2009; 106: 896–902.

Li Z, Shi K, Guan L, Cao T, Jiang Q, Yang Y et al. ROS leads to MnSOD upregulation through ERK2 translocation and p53 activation in selenite-induced apoptosis of NB4 cells. FEBS Lett 2010; 584: 2291–2297.

Han B, Wei W, Hua F, Cao T, Dong H, Yang T et al. Requirement for ERK activity in sodium selenite-induced apoptosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia-derived NB4 cells. J Biochem Mol Biol 2007; 40: 196–204.

Fromigue O, Hay E, Modrowski D, Bouvet S, Jacquel A, Auberger P et al. RhoA GTPase inactivation by statins induces osteosarcoma cell apoptosis by inhibiting p42/p44-MAPKs-Bcl-2 signaling independently of BMP-2 and cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1845–1856.

Nakabayashi H, Shimizu K . HA1077, a Rho kinase inhibitor, suppresses glioma-induced angiogenesis by targeting the Rho-ROCK and the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK/ERK) signal pathways. Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 393–399.

Jimenez-Sainz MC, Murga C, Kavelaars A, Jurado-Pueyo M, Krakstad BF, Heijnen CJ et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 negatively regulates chemokine signaling at a level downstream from G protein subunits. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17: 25–31.

Li X, Liu L, Tupper JC, Bannerman DD, Winn RK, Sebti SM et al. Inhibition of protein geranylgeranylation and RhoA/RhoA kinase pathway induces apoptosis in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 15309–15316.

Tybulewicz VL, Henderson RB . Rho family GTPases and their regulators in lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 630–644.

Mulloy JC, Cancelas JA, Filippi MD, Kalfa TA, Guo F, Zheng Y . Rho GTPases in hematopoiesis and hemopathies. Blood 2010; 115: 936–947.

Titz B, Low T, Komisopoulou E, Chen SS, Rubbi L, Graeber TG . The proximal signaling network of the BCR-ABL1 oncogene shows a modular organization. Oncogene 2010; 29: 5895–5910.

Mali RS, Ramdas B, Ma P, Shi J, Munugalavadla V, Sims E et al. Rho kinase regulates the survival and transformation of cells bearing oncogenic forms of KIT, FLT3, and BCR-ABL. Cancer Cell 2011; 20: 357–369.

Burthem J, Rees-Unwin K, Mottram R, Adams J, Lucas GS, Spooncer E et al. The rho-kinase inhibitors Y-27632 and fasudil act synergistically with imatinib to inhibit the expansion of ex vivo CD34(+) CML progenitor cells. Leukemia 2007; 21: 1708–1714.

Molli PR, Pradhan MB, Advani SH, Naik NR . RhoA: A therapeutic target for chronic myeloid leukemia. Mol Cancer 2012; 11: 16.

Selleri C, Maciejewski JP, Montuori N, Ricci P, Visconte V, Serio B et al. Involvement of nitric oxide in farnesyltransferase inhibitor-mediated apoptosis in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Blood 2003; 102: 1490–1498.

Hebert M, Potin S, Sebbagh M, Bertoglio J, Breard J, Hamelin J . Rho-ROCK-dependent ezrin-radixin-moesin phosphorylation regulates Fas-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat cells. J Immunol 2008; 181: 5963–5973.

Del Re DP, Miyamoto S, Brown JH . Focal adhesion kinase as a RhoA-activable signaling scaffold mediating Akt activation and cardiomyocyte protection. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 35622–35629.

Basile JR, Gavard J, Gutkind JS . Plexin-B1 utilizes RhoA and Rho kinase to promote the integrin-dependent activation of Akt and ERK and endothelial cell motility. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 34888–34895.

Shi Y, Li H, Zhang X, Fu Y, Huang Y, Lui PP et al. Continuous cyclic mechanical tension inhibited Runx2 expression in mesenchymal stem cells through RhoA-ERK1/2 pathway. J Cell Physiol 2011; 226: 2159–2169.

Gallagher ED, Gutowski S, Sternweis PC, Cobb MH . RhoA binds to the amino terminus of MEKK1 and regulates its kinase activity. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 1872–1877.

Ung CY, Li H, Ma XH, Jia J, Li BW, Low BC et al. Simulation of the regulation of EGFR endocytosis and EGFR-ERK signaling by endophilin-mediated RhoA-EGFR crosstalk. FEBS Lett 2008; 582: 2283–2290.

von Kriegsheim A, Baiocchi D, Birtwistle M, Sumpton D, Bienvenut W, Morrice N et al. Cell fate decisions are specified by the dynamic ERK interactome. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11: 1458–1464.

Machacek M, Hodgson L, Welch C, Elliott H, Pertz O, Nalbant P et al. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature 2009; 461: 99–103.

Boulter E, Garcia-Mata R, Guilluy C, Dubash A, Rossi G, Brennwald PJ et al. Regulation of Rho GTPase crosstalk, degradation and activity by RhoGDI1. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12: 477–483.

Duhamel S, Hebert J, Gaboury L, Bouchard A, Simon R, Sauter G et al. Sef downregulation by Ras causes MEK1/2 to become aberrantly nuclear localized leading to polyploidy and neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 626–635.

Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Gotoh Y, Nishida E . Cytoplasmic localization of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase directed by its NH2-terminal, leucine-rich short amino acid sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 20024–20028.

Nobes CD, Hall A . Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion, and adhesion during cell movement. J Cell Biol 1999; 144: 1235–1244.

Shin S, Dimitri CA, Yoon SO, Dowdle W, Blenis J . ERK2 but not ERK1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation via DEF motif-dependent signaling events. Mol Cell 2010; 38: 114–127.

Luo H, Yang Y, Duan J, Wu P, Jiang Q, Xu C . PTEN-regulated AKT/FoxO3a/Bim signaling contributes to reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in selenite-treated colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e481.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Pan Lin for her expertise in IHC. We thank Ms. Zhang Xiaoyan for her help with the TUNEL assay. We thank Mr. Wang Zhifu, Qu Xuebin and Wang Tao for their help. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 31170788, 30970655), the National Natural Science Foundation for Young Scholars of China (Grant No: 31101018), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Grant No: 5082015), the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (Grant No: 20091106110025) and the National Laboratory Special Fund (Grant No: 2060204).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by G Ciliberto

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, F., Jiang, Q., Shi, K. et al. RhoA modulates functional and physical interaction between ROCK1 and Erk1/2 in selenite-induced apoptosis of leukaemia cells. Cell Death Dis 4, e708 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.243

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.243

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Apigenin Attenuates Hippocampal Microglial Activation and Restores Cognitive Function in Methotrexate-Treated Rats: Targeting the miR-15a/ROCK-1/ERK1/2 Pathway

Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

ROCK1 activation-mediated mitochondrial translocation of Drp1 and cofilin are required for arnidiol-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2020)

-

Novel Insights into the Roles of Rho Kinase in Cancer

Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis (2016)

-

miR-125a-3p and miR-483-5p promote adipogenesis via suppressing the RhoA/ROCK1/ERK1/2 pathway in multiple symmetric lipomatosis

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

RhoA/mDia-1/profilin-1 signaling targets microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2015)