Abstract

Glioma is a rare brain tumour with a very poor prognosis and the search for modifiable factors is intense. We reviewed the literature concerning risk factors for glioma obtained in case–control designed epidemiological studies in order to discuss the influence of this methodology on the observed results. When reviewing the association between three exposures, medical radiation, exogenous hormone use and allergy, we critically appraised the evidence from both case–control and cohort studies. For medical radiation and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), questionnaire-based case–control studies appeared to show an inverse association, whereas nested case–control and cohort studies showed no association. For allergies, the inverse association was observed irrespective of study design. We recommend that the questionnaire-based case–control design be placed lower in the hierarchy of studies for establishing cause-and-effect for diseases such as glioma. We suggest that a state-of-the-art case–control study should, as a minimum, be accompanied by extensive validation of the exposure assessment methods and the representativeness of the study sample with regard to the exposures of interest. Otherwise, such studies cannot be regarded as ‘hypothesis testing’ but only ‘hypothesis generating’. We consider that this holds true for all questionnaire-based case–control studies on cancer and other chronic diseases, although perhaps not to the same extent for each exposure–outcome combination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Studies of the aetiology of glioma, the commonest malignant brain tumour, with a very poor prognosis, are urgently needed, specifically to identify modifiable risk factors. The main reason that researchers have used the case–control design as the model of choice for epidemiological studies on the causes of glioma is that it a rare cancer, with an incidence of 4 per 100 000 people (World Standard Population) in Denmark, an incidence typical for a high-income country (Christensen et al, 2003). Furthermore, the design limits the time required to obtain data, the cost is lower than that of more time-consuming designs and a wide range of suspected risk factors can be examined in the same study. In case–control studies, questionnaire data, blood samples and tissue specimens can be obtained from both cases and controls, thereby allowing analysis of both environmental and genetic factors and their interactions.

In questionnaire-based case–control studies, it is anticipated that cases can recall past events with sufficient accuracy. This a priori assumption is somewhat naive in the case of glioma in view of the well-known clinical presentation of the disease. The cancer itself, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and any combination of treatment may strongly influence the overall cognitive capacity of patients. Some have overt cognitive deficits and may therefore be unable to remember past events or have selective recall. Researchers may have to interview a proxy of the patient, as is often the case in case–control studies of risk factors for glioma.

Finding suitable controls presents another challenge. They must be from the same study population as the cases, as the source may influence reported exposures, and selection may be introduced when potential controls decide whether to participate in a study. If these sources of error are systematically different in terms of the exposures of interest from those in the case group, bias will be present. Bias can be addressed partly with statistical tools; however, they require either some idea of the nature and magnitude of bias from validation studies or assumptions about potential bias in sensitivity analyses. Neither necessarily leads to a satisfactory outcome, especially if the results differ substantially according to the assumptions. Despite these potentially serious limitations of case–control studies, there has been no in-depth debate about situations in which questionnaire-based case–control studies are unlikely to provide reliable results. In some narrative syntheses and meta-analytical reviews, the results of such studies contribute equally to the evidence base, even though application of study quality indicators is recommended when summarising evidence. It is therefore important to consider the level of evidence from case–control studies based solely on differential reconstruction of past exposures as compared with that from prospective studies for investigating glioma, when reconstruction of exposure is hampered by the outcome itself.

In this review, we critically appraise the evidence from both case–control and cohort studies of three risk factors for glioma in humans: medical radiation, exogenous hormone use and allergy. The objective is to provide some insight into the difficulty associated with choosing a study design when studying the risk factors for glioma. We also propose considerations for applying scientific weight to the results of case–control studies in this context.

We searched the Medline–PubMed database on 18 November 2015 using the following search strategy:

Search ((‘Glioma/epidemiology’[Majr] OR (glioma AND epidemiology))) AND ((((‘Risk Factors’[Mesh]) OR ‘Environment and Public Health’[Mesh])) OR (Risk OR exposure OR factor* OR cause*)) Filters: Humans; Meta-Analysis; Review; Systematic Reviews

OR

Search (((((‘Glioma/epidemiology’[Majr] OR (glioma AND epidemiology))) AND ((((‘Risk Factors’[Mesh]) OR ‘Environment and Public Health’[Mesh])) OR (Risk OR exposure OR factor* OR cause*))) AND Humans[Mesh])) AND (((‘Case-Control Studies’[Mesh]) OR ‘Cohort Studies’[Mesh]) AND Humans[Mesh]) Filters: Humans

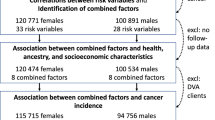

This search provided 3018 hits. Using the inclusion criteria English language paper, adult glioma, case–control study or cohort study and excluding reviews and/or meta-analyses, overview or commentary, qualitative methodology, children and adolescents, genetic exposures and mortality or survival as the outcome, we identified reports of original studies that included the three selected risk factors for glioma. Our search was intended to be neither comprehensive nor systematic for this review. We are aware that we did not identify some studies, such as those in which the word ‘glioma’ was not in the title, abstract or keywords and those in which none of the three risk factors was mentioned in the title or abstract.

From the selected papers, we extracted the characteristics of the study. We then compared the evidence from studies based on recall by cases and controls with that from studies with either a case–control design, with objective (recall-independent) assessment of exposure or a prospective cohort design.

We selected 30 case–control studies and six cohort studies on the association between glioma and medical radiation (Preston-Martin et al, 1989; Neuberger et al, 1991; Schlehofer et al, 1992; Ryan et al, 1992; Zampieri et al, 1994; Ruder et al, 2006; Blettner et al, 2007; Davis et al, 2011), exogenous hormone use (Huang et al, 2004; Hatch et al, 2005; Wigertz et al, 2006; Silvera et al, 2006; Benson et al, 2008, 2015; Felini et al, 2009; Michaud et al, 2010; Kabat et al, 2011; Andersen et al, 2013; Anic et al, 2014; 2015) or allergic diseases (Cicuttini et al, 1997; Schlehofer et al, 1999, 2011; Wiemels et al, 2002, 2004, 2009; Brenner et al, 2002; Schwartzbaum et al, 2003; Schoemaker et al, 2006; Wigertz et al, 2007; Scheurer et al, 2008; Berg-Beckhoff et al, 2009; Il’yasova et al, 2009; 2009; McCarthy et al, 2011; Calboli et al, 2011; Turner et al, 2013; Cahoon et al, 2014). Table 1 lists the key characteristics of the selected studies.

Medical radiation: information from participants only

Ionising radiation is a long-established human carcinogen. Early cohort studies of patients who received radiation treatment to the scalp to treat tinea capitis or skin haemangioma during childhood had an increased risk for glioma, especially after treatment at an early age (see, e.g., Ron et al, 1988). Early case–control studies suggested increased risks for glioma after exposure to dental X-rays or X-rays to the head and neck (Preston-Martin et al, 1989; Neuberger et al, 1991; Ryan et al, 1992; Schlehofer et al, 1992). In contrast, the German part of the Interphone study (a multinational interview-based case–control study on mobile phone use and other risk factors for brain tumours, acoustic neuroma and salivary gland tumours) indicated that exposure to any medical ionising radiation significantly reduced the risk for glioma (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48–0.83) in a study of 366 glioma patients (of whom 11% reported information on exposure through proxies) and 1538 controls (Blettner et al, 2007). Other research groups have reported a similar protective effect of medical ionising radiation. In a study in Italy in 1984, of 195 cases and hospital controls, in which all information was obtained from proxies, the OR for any diagnostic X-ray was 0.4 (95% CI, 0.1–1.0; Zampieri et al, 1994). In two studies in the USA with 798 and 205 cases (proportions of proxies not reported), reduced ORs were found after exposure to full-mouth dental X-rays (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61–0.92; Ruder et al, 2006) and after one or more yearly dental X-rays or three or more full-mouth X-rays (0.60; 95% CI, 0.21–1.73 to 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40–1.21; Davis et al, 2011). In personal communications, we have been informed that medical radiation appears to be protective against glioma in the entire Interphone data set and that similar results were obtained in the Gliogene study. Although authors usually appropriately discuss the possibility of chance findings, residual confounding and (more importantly) recall bias, use of proxies and selection bias, data are required to estimate the magnitude and direction of the potential error; otherwise, most of the conclusions remain speculative. Most case–control studies continue to rely on self-reported information, whereas validation from records of medical radiation or dental records should be a minimal quality assurance component of studies. This may be difficult in countries where X-ray machines are available in all hospitals, big or small, and even in some general practices, so that it would be virtually impossible to review all the records for false negatives (that is, examinations not reported by study participants). It should, however, be feasible on a small sample.

Exogenous hormones: self-reported use versus prescription data

Two methods have been used to collect information on exposure in studies of the relation between use of exogenous hormones and glioma: self-reported use and prescription data. In a case–control study in the USA with 619 women with glioma and 650 controls, self-reported use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was associated with an OR of 0.56 (95% CI, 0.37–0.84; Felini et al, 2009). This result is in line with those of a number of other case–control studies of self-reported use of oral contraceptives or HRT, reported separately (Huang et al, 2004; Hatch et al, 2005; Wigertz et al, 2006; Anic et al, 2014), which did not, however, reach statistical significance. In two case–control studies nested in population-based registries, with data on prescriptions collected prospectively and independently of the study hypothesis, use of HRT did not decrease the risk for glioma, based on 689 cases (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.93–1.40) and 658 cases (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.8–1.1; Benson et al, 2015 and Andersen et al, 2013). These results, based on administrative sources, corroborated those of several very large prospective cohort studies with self-reported data on use of oral contraceptives or HRT obtained before diagnosis of a glioma (Silvera et al, 2006; Benson et al, 2008; Michaud et al, 2010; Kabat et al, 2011). Overall, therefore, relying on self-reported information on use of exogenous hormones obtained retrospectively resulted in systematically lower risk estimates than when exposure was measured prospectively or from prescription data, when no convincing reductions in risk were observed.

Allergy: same direction in risk irrespective of study design

The search of an immune factor that may have a role in glioma aetiology has led to studies of several different definitions of outcomes—ranging from self-reported allergic conditions or autoimmune disorders, discharge records of allergic disorders and use of serum IgE levels as a measure of a hyperactive immune system. Several case–control studies showed consistently that self-reported allergic conditions protect against glioma. For example, in the International Adult Brain Tumour Study, with 1178 glioma patients (26% of whom reported through proxies) and 2493 population controls, an OR of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.49–0.71) was found for any self-reported allergy (Schlehofer et al, 1999). Other case–control studies found similarly reduced ORs; these often had substantial proportions of proxy informants: 44% (Cicuttini et al, 1997), 24% (Wiemels et al, 2002), 24% (Brenner et al, 2002), 13% (Wigertz et al, 2007), 4% (Scheurer et al, 2008), 3% (Berg-Beckhoff et al, 2009), 24% (Wiemels et al, 2009) and 17% (Turner et al, 2013); others did not provide information on the proportion of proxies (Wiemels et al, 2004; Schoemaker et al, 2006; Il’yasova et al, 2009; McCarthy et al, 2011). Two Swedish cohorts who self-reported allergies had non-significantly reduced risks for glioma: OR, 0.45 (95% CI, 0.19–1.07) among twins born in 1986–1925 but a nonsignificantly increased risk (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.48–2.48) among twins born in 1926–1958 (Schwartzbaum et al, 2003). In a combined analysis of the two twin cohorts and discharge records of immune-related diseases, including both atopic allergic diseases as well as autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and so on, as the exposure measure, the risk was reduced but not significantly (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.14–1.48).

The biological marker immunoglobuline E (IgE) may provide more specificity and reduce bias stemming from self-report. In a case–control study from 2004, both self-reported allergies and IgE levels were reversely associated with gliomas in 258 cases and 289 controls but, as expected, concordance between the two outcomes was not high (Wiemels et al, 2004). In a further study from 2009, both self-reported allergies and IgE levels were reversely associated in 535 cases and 532 controls, but analyses showed that IgE levels obtained in glioma patients were affected by treatment with telozomide, underscoring the need for prospectively collected data (Wiemels et al, 2009). A case–control study nested in the EPIC cohort (Schlehofer et al, 2011) and thus with prospectively collected data on serum IgE levels reported a statistically nonsignificant OR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.51–1.06) based on 275 cases. Another case–control study, nested in four large cohorts in the USA with 181 cases of glioma, found an almost identical OR of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.51–1.03) for a serum IgE level above normal (Calboli et al, 2011). A cohort study of hospital discharge records of 4.5 million men with a mean 12-year follow-up and 4383 events of glioma showed that any allergy was associated with an HR for glioma of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.72–1.01) with a latency of >2 years and 0.6 (95% CI, 0.4–0.8) with a latency of >10 years (Cahoon et al, 2014). In a meta-analyses of the 14 studies in the international Gliogene case–control study, published after our literature search, with 4533 cases and 4177 controls and <10% proxies, respiratory allergy was associated with an OR of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.58–0.90; Amirian et al, 2016a).

Imprecisely defined exposures such as allergic disease probably affect the validity of the findings of both case–control and cohort studies. The heterogeneous description of allergy in studies, different levels of detail in self-reporting on individual allergies and use of objective measures of serum IgE levels or discharge records further complicate interpretation of the results. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that most studies of any design, type of measure and size indicate that allergy or a hyperactive immune system, through some as yet unidenfied biological mechanisms might be protective against the development of glioma.

Synthesis of the three examples

In two of our examples, medical radiation and HRT, questionnaire-based case–control studies appeared to show an inverse association, whereas nested case–control and cohort studies showed no association. For allergies, the inverse association is observed irrespective of study design. If the inverse associations with medical radiation and HRT use are spurious, possible explanations are over-reporting by controls, under-reporting by cases or selection bias in relation to the exposure of interest. Over-reporting by controls seems unlikely, unless the time between the reference date (censoring of risk time) and the interview date is long, when controls may incorrectly remember the dates of examinations and report those occurring after censoring of the risk time, as observed in a case–control study on paediatric brain tumours in Germany (Schüz et al, 2001). Selection bias may have some role, as medical radiation and HRT use are more common among more affluent people, while participation as a control is often associated with higher education and income. Underreporting is a concern. It might occur because a patient with the very serious diagnosis of a glioma might view other medical events as less important and could easily be forgotten in an interview. The last finding is curious, because, for environmental exposures, validation studies suggest over-reporting or exaggeration by cases (for instance, in studies on mobile phone use or occupational exposure), perhaps because they try to not miss reporting something they may consider relevant in terms of their cancer diagnosis. (For discussions on bias in case–control studies on brain tumours, see, for example, Vrijheid et al, 2006, 2009).

After 30 years of research, we still do not know much about what causes glioma or protects people from the disease. In the search for causality, many researchers who are systematically evaluating the evidence give more weight to that from cohort studies than from case–control studies (e.g., Cochrane reviews); others go as far as considering case–control studies useful only for hypothesis generating because of their retrospective nature (Mann, 2003). In many systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the peer-reviewed literature; however, there is a tendency to categorise the evidence from case–control studies with evidence derived from prospective cohort studies and to give them equal weight. In studying glioma, we consider it critical that studies based on the recall of patients with a disease that affects the brain and possibly cognition should not be given the same weight as nested case–control studies or cohort studies. In addition to the limitations inherent in questionnaire-based case–control studies on other diseases, the risk for recall bias among cases makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Validation studies of recall of exposures by glioma cases and by controls often show that cases recall the past differently from controls (Vrijheid et al, 2006, 2009). The treatment and even the symptoms that arise before treatment, due to the presence of the tumour, may influence cognitive function, underscoring these objections. In studies of glioma, the widespread acceptance of information obtained from the closest relative—a proxy—adds to the problem of the accuracy of self-reported information. Going back to our examples, would proxies really know about the dental X-rays that the patient had during childhood? Recall bias is an issue not only for the exposure of interest but also for potential confounders in analyses of the exposure–disease relationship, as inaccurately measured confounders obviate appropriate adjustment.

As we have illustrated, studies in which information on exposure is obtained from sources other than memory for both cases and controls and in which the information on outcome is from high quality sources, are more reliable, depending on the completeness and quality of the data that can be obtained.

The cohort design is not free of problems, but it is less vulnerable to methodological errors than case–control studies that rely on the memory of cases and controls. The cohort design is therefore the preferred type for observational studies. Nevertheless, because glioma is a rare event, the case–control design may be the only one possible. During critical appraisal of the evidence derived from such studies, however, quality indicators should be applied, as they should for cohort studies. These quality indicators should address the study population (sampling frame, response rates), exposure measures (ideally showing results from validations), and discussion of potential bias affecting the risk estimation.

The superiority of the cohort design and/or access to data obtained independently of the hypothesis in studies of potential risk factors for cancer have been illustrated by cohort studies of various issues, for example, that abortions increase the risk for breast cancer (Melbye et al, 1997) and that our minds cause cancer (Johansen, 2012). One may say that when studying i.e. low-dose radiation and rare outcomes such as gliomas with complicating problems of recall bias and lack of validation the question cannot be reduced to just choosing cohort studies over case–control studies. Cohort studies may actually not be feasible for evaluation of this exposure. One solution might instead be to extrapolate from cohort studies with greater ranges of exposure like atomic bomb survivors or people exposed to nuclear accidents. Poorly conducted studies give rise to risk, as their outcomes often contribute to public concern and may shift the focus from the relevant to the irrelevant, as for instance in the debate about cancer risks and mobile technologies.

Observational studies on the risk factors for glioma, i.e. reports from the early case–control studies conducted at the University of California at San Francisco (USA; see, e.g., Wrensch et al, 2000) and the University of California at Los Angeles (USA; Preston-Martin et al, 1989), coordinated by the US National Cancer Institute (Inskip et al, 2001), the first international case–control study (Schlehofer et al, 1999), the Interphone study (Cardis et al, 2007) and probably also the most recent Gliogene case–control study (Malmer et al, 2007), do not provide much evidence on what causes this devastating cancer. Thus, despite all the resources that went into those studies, the results did not provide striking evidence on which to base prevention. Nevertheless, as lifestyle and environmental factors were studied comprehensively, the results may suggest that not many of the usual cancer-causing suspects have an important role in glioma aetiology. This is an important finding to be acknowledged and suggests that for the identification of causes novel ideas are needed. Recent reports on genetic risk factors for glioma suggest that these factors do have a crucial role in the risk pattern (Amirian et al, 2016b).

The criteria for causality are the strength of the evidence, consistency across populations, specificity, temporality, dose–response and biological plausibility (Hill, 1965). The temporal criterion should always be addressed in evaluating the evidence, whereas in case–control studies, unless secondary data sources can be used, the information is collected after diagnosis of a disease, that is, the reverse sequence in temporality. Furthermore, there are major problems in self-reporting, as cases are aware of having a fatal disease and may unconsciously change their way of looking at past events. Even physical measurements should be evaluated for the representativeness of contemporary measurements of exposure during the aetiologically relevant period, which might have been decades previously.

On the basis of this review, we recommend that the case–control design be placed lower in the hierarchy of studies for establishing cause-and-effect for diseases such as glioma, which pose challenges for accurate collection of retrospective data. A state-of-the-art case–control study should as a minimum, be accompanied by extensive validation of the exposure assessment methods and the representativeness of the study sample with regard to the exposures of interest. Otherwise, such studies cannot be termed ‘hypothesis testing’ but only ‘hypothesis generating’. We consider that this holds true for all questionnaire-based case–control studies on all cancers and chronic diseases, although perhaps not to the same extent for each exposure–outcome combination. For example, case–control studies clearly linked smoking with lung cancer in the 1950s, prenatal radiation to the fetus with childhood leukemia in the late 1950s/early 1960s, postmenopausal oestrogens with uterine endometrial cancer in the 1960s and diethylstilbestrol with vaginal adenocarcinoma in 1971. Almost all known risk factors for breast cancer were identified in case–control studies and much of the evidence that identified smoking and types of tobacco as the cause of about 50% of bladder cancer was based on case–control studies. However, this list does not include risk factors for glioma and these earlier studies, in some cases, showed risk estimates robust to such a degree that even potential bias could not hamper the associations observed.

We hope that the examples we have provided underscore our points and that our recommendation will be taken into account in ranking the evidence obtained from case–control studies and also in the design of such studies in cancer epidemiology.

References

Amirian ES, Zhou R, Wrensch MR, Olson SH, Scheurer ME, Il'yasova D, Lachance D, Armstrong GN, McCoy LS, Lau CC, Claus EB, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Schildkraut J, Ali-Osman F, Sadetzki S, Johansen C, Houlston RS, Jenkins RB, Bernstein JL, Merrell RT, Davis FG, Lai R, Shete S, Amos CI, Melin BS, Bondy ML (2016a) Approaching a scientific consensus on the association between allergies and glioma risk: a report from the glioma international case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25: 282–290.

Amirian ES, Armstrong GN, Zhou R, Lau CC, Claus EB, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Il'yasova D, Schildkraut J, Ali-Osman F, Sadetzki S, Johansen C, Houlston RS, Jenkins RB, Lachance D, Olson SH, Bernstein JL, Merrell RT, Wrensch MR, Davis FG, Lai R, Shete S, Amos CI, Scheurer ME, Aldape K, Alafuzoff I, Brännström T, Broholm H, Collins P, Giannini C, Rosenblum M, Tihan T, Melin BS, Bondy ML (2016b) The glioma international case-control study: a report from the Genetic Epidemiology of Glioma International Consortium. Am J Epidemiol 183: 85–91.

Andersen L, Friis S, Halls J, Ravn P, Gaist D (2013) Hormone replacement therapy and risk of glioma: a nationwide nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol 37: 876–880.

Anic GM, Madden MH, Nabors B, Olson JJ, LaRocca RV, Thompson ZJ, Pamnani SJ, Forsyth PA, Thompson RC, Egan KM (2014) Reproductive factors and risk of primary brain tumors in women. J Neurooncol 118: 297–304.

Benson VS, Pirie K, Green J, Casabonne D, Berai V the Million Women Study Collaboration (2008) Lifestyle factors and primary glioma and meningioma tumours in the Million Women Study cohort. Br J Cancer 99: 185–190.

Benson VS, Kirichek O, Beral V, Green J (2015) Menopausal hormone therapy and central nervous system tumor risk: large UK prospective study and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 136: 2369–2377.

Berg-Beckhoff G, Schüz J, Blettner M, Münster E, Schlaefer K, Wahrendorf J, Schlehofer B (2009) History of allergic disease and epilepsy and risk of glioma and meningioma (Interphone study group, Germany). Eur J Epidemiol 24: 433–440.

Blettner M, Schlehofer B, Samkange-Zeeb F, Berg G, Schlafer K, Schüz J (2007) Medical exposure to ionising radiation and the risk of brain tumours: Interphone study group, Germany. Eur J Cancer 43: 1990–1998.

Brenner AV, Linet MS, Fine HA, Shapiro WR, Selker RG, Black PM, Inskip PD (2002) History of allergies and autoimmune diseases and risk of brain tumors in adults. Int J Cancer 99: 252–259.

Cahoon EK, Inskip PD, Gridley G, Brenner AV (2014) Immune-related conditions and subsequent risk of brain cancer in a cohort of 4.5 million male US veterans. Br J Cancer 110: 1825–1833.

Calboli FCF, Cox DG, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Ma J, Stampfer M, Willett WC, Tworoger SS, Hunter DJ, Camargo-Jr CA, Michaud DS (2011) Prediagnostic plasma IgE levels and risk of adult glioma in four prospective cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 1588–1595.

Cardis E, Richardson L, Deltour I, Armstrong B, Feychting M, Johansen C, Kilkenny M, McKinney P, Modan B, Sadetzki S, Schüz J, Swerdlow A, Vrijheid M, Auvinen A, Berg G, Blettner M, Bowman J, Brown J, Chetrit A, Christensen HC, Cook A, Hepworth S, Giles G, Hours M, Iavarone I, Jarus-Hakak A, Klaeboe L, Krewski D, Lagorio S, Lönn S, Mann S, McBride M, Muir K, Nadon L, Parent ME, Pearce N, Salminen T, Schoemaker M, Schlehofer B, Siemiatycki J, Taki M, Takebayashi T, Tynes T, van Tongeren M, Vecchia P, Wiart J, Woodward A, Yamaguchi N (2007) The Interphone study: design, epidemiological methods, and description of the study population. Eur J Epidemiol 22: 647–664.

Christensen HC, Kosteljanetz M, Johansen C (2003) Incidences of gliomas and meningiomas in Denmark 1943 to 1997. Neurosurgery 52: 1327–1334.

Cicuttini FM, Hurley SF, Forbes A, Donnan GA, Salzberg M, Giles GG, McNeil JJ (1997) Association of adult glioma with medical conditions, family and reproductive history. Int J Cancer 71: 203–207.

Davis F, Il’yasova D, Rankin K, McCarthy K, McCarthy B, Bigner DD (2011) Medical diagnostic radiation exposures and risk of gliomas. Radiation Res 175: 790–796.

Felini MJ, Olshan AF, Schroeder JC, Carozza SE, Miike R, Rice T, Wrensch M (2009) Reproductive factors and hormone use and risk of adult gliomas. Cancer Causes Control 20: 87–96.

Hill AB (1965) The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 58: 295–300.

Hatch EE, Linet MS, Zhang J, Fine HA, Shapiro WR, Selker RG, Black PM, Inskip P (2005) Reproductive and hormonal factors and risk of brain tumors in adult females. Int J Cancer 114: 797–805.

Huang K, Whelan EA, Ruder AM, Ward EM, Deddens JA, Davis-King KE, Carreón T, Waters MA, Butler MA, Calvert GM, Schulte PA, Zivkovich Z, Heineman EF, Mandel JS, Morton RF, Reding DJ, Rosenman KD the Brain Cancer Collaborative Study Group (2004) Reproductive factors and risk of glioma in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 1583–1588.

Il’yasova D, McCarthy B, Marcello J, Schildkrau JM, Moorman PG, Krishnamachari B, Ali-Osman F, Bigner DD, Davis F (2009) Association between glioma and history of allergies, asthma and eczema: a case-control study with three groups of controls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18: 1232–1238.

Inskip PD, Tarone RE, Hatch EE, Wilcosky TC, Shapiro WR, Selker RG, Fine HA, Black PM, Loeffler JS, Linet MS (2001) Cellular-telephone use and brain tumors. N Engl J Med 344: 79–86.

Johansen C (2012) Mind as a risk factor for cancer – some comments. Psychooncology 21: 922–926.

Kabat GC, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Rohan TE (2011) Reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use and risk of adult glioma in women in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health study. Int J Cancer 128: 944–950.

Malmer B, Adatto P, Armstrong G, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Bernstein JL, Claus E, Davis F, Houlston R, Il'yasova D, Jenkins R, Johansen C, Lai R, Lau C, McCarthy B, Nielsen H, Olson SH, Sadetzki S, Shete S, Wiklund F, Wrensch M, Yang P, Bondy M (2007) Gliogene: an international consortium to understand familial glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 1730–1734.

Mann CJ (2003) Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J 20: 54–60.

McCarthy BJ, Rankin K, Il’yasova D, Erdal S, Vick N, Ali-Osman F, Bigner DD, Davis F (2011) Assessment of type of allergy and antihistamine use in the development of glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 370–378.

Melbye M, Wohlfahrt J, Olsen JH, Frisch M, Westergaard T, Helweg-Larsen K, Andersen PK (1997) Induced abortion and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 336: 81–85.

Michaud DL, Gallo V, Schlehofer B, Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K, Dahm CC, Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Boeing H, Schütze M, Trichopoulou D, Bamia C, Kyrozis A, Sacerdote C, Agnoli C, Palli D, Tumino R, Mattiello A, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ros MM, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, Lund E, Bakken K, Gram IT, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Dorronsoro M, Sánchz MJ, Rodríguez L, Duell EJ, Hallmans G, Melin BS, Manjer J, Borgquist S, Khaw K-T, Wareham N, Allen NE, Tsilidis KK, Romieu I, Rinaldi S, Vineis P, Riboli E (2010) Reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use in relation to risk of glioma and meningioma in a large European cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19: 2562–2569.

Neuberger JS, Brownson RC, Morantz RA, Chin TDY (1991) Association of brain cancer with dental x-rays and occupation in Missouri. Cancer Detect Prev 15: 31–34.

Preston-Martin S, Mack W, Henderson BE (1989) Risk factors for gliomas and meningiomas in males in Los Angeles County. Cancer Res 49: 6137–6143.

Ron E, Modan B, Boice JD Jr (1988) Mortality after radiotherapy for ringworm of the scalp. Am J Epidemiol 127: 713–725.

Ruder AM, Waters MA, Carreón T, Butler MA, Davis-King KE, Calvert GM, Schulte PA, Ward EM, Connally LB, Lu J, Wall D, Zivkovich Z, Heineman EF, Mandel JS, Morton RF, Reding DJ, Rosenman KD Brain Cancer Collaborative Study Group (2006) The Upper Midwest Health Study: a case-control study of primary intracranial gliomas in farm and rural residents. J Agric Saf Health 12: 255–274.

Ryan P, Lee MW, North B, McMichael AJ (1992) Amalgam fillings, diagnostic dental x-rays and tumours of the brain and meninges. Oral Oncol Eur J Cancer 28B: 91–95.

Scheurer ME, El-Zein R, Thompson PA, Aldape KD, Levin VA, Gilbert MR, Weinberg JS, Bondy ML (2008) Long-term anti-inflammatory and antihistamine medication use and adult glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 1277–1281.

Schlehofer B, Blettner M, Becker N, Martinsohn C, Wahrendorf J (1992) Medical risk factors and the development of brain tumors. Cancer 69: 2541–2547.

Schlehofer B, Blettner M, Preston-Martin S, Niehoff D, Wahrendorf J, Arslan A, Ahlbom A, Choi WN, Giles GG, Howe GR, Little J, Ménégoz F, Ryan P (1999) Role of medical history in brain tumour development. Results from the international adult brain tumour study. Int J Cancer 82: 155–160.

Schlehofer B, Siegmund B, Linseisen J, Schüz J, Rohrman S, Becker S, Michaud D, Melin B, Bas Bueno-de-Mesquitaeri H, Peeters PHM, Vineis P, Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K, Romieu I, Boieng H, Aleksandrova K, Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Lagiou P, Sacerdote C, Palli D, Panico S, Sieri S, Tuminoarricarte A, Borgquist S, Manjer J, Gallo V, Allen NE, Key TJ, Riboli E, Kaaks R, Wahrendorf J (2011) Primary brain tumours and specific serum immunoglobulin E: a case-control study nested in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Allergy 66: 1434–1441.

Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow A, Hepworth SJ, McKinney PA, van Tongeren M, Muir KR (2006) History of allergies and risk of glioma in adults. Int J Cancer 119: 2165–2172.

Schüz J, Kaletsch U, Kaatsch P, Meinert R, Michaelis J (2001) Risk factors for pediatric tumors of the central nervous system: results from a German population-based case-control study. Med Pediatr Oncol 36: 274–282.

Schwartzbaum J, Jonsson F, Ahlbom A, Preston-Martin S, Lönn S, Söderberg KC, Feychting M (2003) Cohort studies of association between self-reported allergic conditions, immune-related diagnoses and glioma and meningioma risk. Int J Cancer 106: 423–428.

Silvera SAN, Miller AB, Rohan TE (2006) Hormonal and reproductive factors and risk of glioma: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer 118: 1321–1324.

Turner MC, Krewski D, Armstrong BK, Chetrit A, Giles GG, Hours M, McBride ML, Parent M-E, Sadetzki S, Siemiatycki J, Woodward A, Cardis E (2013) Allergy and brain tumors in the Interphone study: pooled results from Australia, Canada, France, Israel, and New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control 24: 949–960.

Vrijheid M, Deltour I, Krewski D, Sanchez M, Cardis E (2006) The effects of recall errors and of selection bias in epidemiologic studies of mobile phone use and cancer risk. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 16: 371–384.

Vrijheid M, Armstrong BK, Bédard D, Brown J, Deltour I, Iavarone I, Krewski D, Lagorio S, Moore S, Richardson L, Giles GG, McBride M, Parent ME, Siemiatycki J, Cardis E (2009) Recall bias in the assessment of exposure to mobile phones. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 19: 369–381.

Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Sison JD, Miike R, McMillan A, Wrensch M (2002) History of allergies among adults with glioma and controls. Int J Cancer 98: 609–615.

Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Patoka J, Moghadassi M, Chew T, McMillan A, Miike R, Barger G, Wrensch M (2004) Reduced immunoglobulin E and allergy among adults with glioma compared with controls. Cancer Res 64: 8464–8473.

Wiemels JL, Wilson D, Pater C, Patoka J, McCoy L, Rice T, Schwarzbaum J, Heimberger A, Sampson JH, Chang S, Prados M, Wiencke JK, Wrensch M (2009) IgE, allergy, and risk of glioma: update from the San Francisco Bay Area Adult Glioma Study in the temozolomide era. Int J Cancer 125: 680–687.

Wigertz A, Lönn S, Schwartzbaum J, Hall P, Auvinen A, Christensen HC, Johansen C, Klæboe L, Salminen T, Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Tynes T, Feychting M (2007) Allergic conditions and brain tumor risk. Am J Epidemiol 166: 941–950.

Wigertz A, Lönn S, Mathiesen T, Ahlbom A, Hall P, Feychting M the Swedish Interphone Study Group (2006) Risk of brain tumors associated with exposure to exogenous female sex hormones. Am J Epidemiol 164: 629–636.

Wrensch M, Miike R, Lee M, Neuhaus J (2000) Are prior head injuries or diagnostic X-rays associated with glioma in adults? The effects of control selection bias. Neuroepidemiology 19: 234–244.

Zampieri P, Meneghini F, Grigoletto F, Gerosa M, Licata C, Casentini L, Longatti PL, Padoan A, Mingrino S (1994) Risk factors for cerebral glioma in adults: a case-control study in an Italian population. J Neurooncol 19: 61–67.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Johansen, C., Schüz, J., Andreasen, AM. et al. Study designs may influence results: the problems with questionnaire-based case–control studies on the epidemiology of glioma. Br J Cancer 116, 841–848 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.46

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.46

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of a novel antisense lncRNA TP73-AS1 polymorphisms and expression with colorectal cancer susceptibility and prognosis

Genes & Genomics (2022)

-

Searching for causal relationships of glioma: a phenome-wide Mendelian randomisation study

British Journal of Cancer (2021)

-

Testing for causality between systematically identified risk factors and glioma: a Mendelian randomization study

BMC Cancer (2020)

-

Update on the effect of exogenous hormone use on glioma risk in women: a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2018)

-

Impact of atopy on risk of glioma: a Mendelian randomisation study

BMC Medicine (2018)