Abstract

Background:

Increasing data suggest that aspirin use may improve cancer survival; however, the evidence is sparse for ovarian cancer.

Methods:

We examined the association between postdiagnosis use of low-dose aspirin and mortality in a nationwide cohort of women with epithelial ovarian cancer between 2000 and 2012. Information on filled prescriptions of low-dose aspirin, dates and causes of death, and potential confounding factors was obtained from nationwide Danish registries. We used Cox regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ovarian cancer-specific or other-cause mortality associated with low-dose aspirin use.

Results:

Among 4117 patients, postdiagnosis use of low-dose aspirin was associated with HRs of 1.02 (95% CI: 0.87–1.20) for ovarian cancer mortality and 1.06 (95% CI: 0.77–1.47) for other-cause mortality. Hazard ratios remained neutral according to patterns of low-dose aspirin use, including prediagnosis use or established mortality predictors.

Conclusions:

Low-dose aspirin use did not reduce mortality among ovarian cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite some advances in treatment modalities, the survival of ovarian cancer has hardly improved for decades and identification of modifiable factors that can improve the prognosis of ovarian cancer patients remains a high priority (Allemani et al, 2015).

Several epidemiologic studies suggest improved cancer outcomes with regular aspirin use among patients with clinically manifest cancer, and a number of randomised clinical trials are currently ongoing to evaluate the role of aspirin in the treatment of common cancers, notably colorectal cancer (Coyle et al, 2016; Elwood et al, 2016). The exact mechanisms behind the antineoplastic effects of aspirin remain to be established (Thun et al, 2012; Umar et al, 2016). For ovarian cancer, some studies in murine models and human cell lines have demonstrated an interaction between platelets and proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis of ovarian tumours, suggesting a role for aspirin via the antiplatelet effect (Cooke et al, 2015; Cho et al, 2017); however, other mechanisms have also been suggested (Hudson et al, 2008; Gates et al, 2010). Only few epidemiologic studies of ovarian cancer patients have evaluated outcomes associated with aspirin use and the results have been too equivocal to allow efficient design of clinical trials (Minlikeeva et al, 2015; Nagle et al, 2015; Bar et al, 2016; Dixon et al, 2017; Verdoodt et al, 2017b). A pooled analysis of 12 studies within the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC) reported a neutral association between aspirin use and overall survival among ovarian cancer patients; however, aspirin exposure was self-reported and only prediagnosis use was evaluated (Dixon et al, 2017). The influence of postdiagnosis aspirin use, a clinically more relevant exposure, has been explored in only one small cohort study reporting a statistically significant 50% reduction in overall mortality with aspirin use (Bar et al, 2016). This prompted us to conduct a cohort study of postdiagnosis low-dose aspirin use and mortality among ovarian cancer patients in Denmark, using the unique Danish nationwide registries.

Materials and methods

From the Danish Cancer Registry, we identified all women aged 30–84 years with incident primary epithelial ovarian cancer between 2000 and 2012 and no history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer). Information on filled prescriptions for low-dose aspirin and other drugs, tumour and patient characteristics, comorbid conditions, and mortality outcomes were retrieved from nationwide demographic, prescription, and patient registries, using the unique civil registration number assigned to all Danish residents for linkage. The Supplementary Material provides a detailed description of the registries, with codes for ovarian cancer, drug exposure, and covariates.

The study outcomes were ovarian cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. Patients were followed from 1 year after ovarian cancer diagnosis until death, migration, or end of the study (31 December 2013).

We defined postdiagnosis use of low-dose (75–150 mg) aspirin as ⩾1 prescription filled after the ovarian cancer diagnosis. Prediagnosis use of low-dose aspirin was defined as ⩾1 prescription within 5 years before the ovarian cancer diagnosis. In the primary analysis, we assessed postdiagnosis use of low-dose aspirin as a time-varying covariate lagged by 1 year (Chubak et al, 2013). Thus, postdiagnosis low-dose aspirin users were regarded as non-users until 1 year after their first prescription.

In secondary analyses, we evaluated the influence of timing of low-dose aspirin use by developing a supplementary time-varying exposure matrix: (1) no pre- or postdiagnosis use (reference group), (2) prediagnosis use only, (3) pre- and postdiagnosis use, and (4) postdiagnosis use only.

In two sensitivity analyses with fixed exposure periods, low-dose aspirin use was assessed from time of diagnosis until the start of follow-up at 1 or 3 years following the ovarian cancer diagnosis, and was considered invariable thereafter (Verdoodt et al, 2017a).

We used Cox proportional hazard regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between postdiagnosis low-dose aspirin use and ovarian cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. Minimally adjusted analyses included age at diagnosis, clinical stage, and year of diagnosis. Fully adjusted models further included tumour histology, chemotherapy, highest achieved education, disposable income, marital status, comorbid conditions, and non-aspirin drug use (Table 1 and Supplementary Material). The proportional hazards assumption was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Finally, we evaluated the influence of competing risks as a result of death from other causes using the subdistribution hazards model proposed by Fine and Gray adapted for time-dependent covariates (Fine and Gray, 1999).

All analyses were performed using the R statistical software version 3.2.3 and the survival package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015; Therneau, 2015). STROBE guidelines were used to outline this study (von Elm et al, 2007). The Danish Data Protection Agency and Statistics Denmark’s Scientific Board approved the study. According to Danish law, ethical approval is not required for registry-based studies (Thygesen et al, 2011).

Results

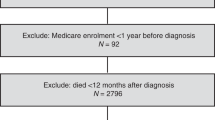

Among 5439 eligible women with a primary diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer, 4117 were alive 1 year after the diagnosis and included in our study. During a mean follow-up of 3.6 years (maximum 13 years), 2245 (55%) patients died and of these, 1903 (85%) women died from ovarian cancer. Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

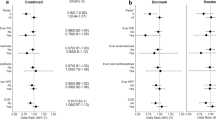

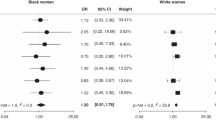

In the primary, time-varying analysis, we saw no association between postdiagnosis use of low-dose aspirin and ovarian cancer (HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.87–1.20) or other-cause (HR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.77–1.47) mortality (Table 2). Further, we observed no substantial variation in HRs according to estimated dose (tablet size), cumulative amount of postdiagnosis low-dose aspirin use, or with timing of use (Table 2). Stratification according to tumour histology (Table 3), age at diagnosis, clinical stage, or year of diagnosis (Online Supplementary eTable 2) did not materially influence the associations.

We also observed overall neutral associations for ovarian cancer-specific and other-cause mortality in sensitivity analyses, except for an increased HR with short duration of low-dose aspirin use in the 3-year analysis; however, these estimates were based on small numbers (Supplementary eTable 3). Finally, analyses accounting for competing risks (Fine and Gray) exhibited results similar to those of the primary analyses (data not shown).

Discussion

Our finding of a null association between use of low-dose aspirin and mortality after ovarian cancer is compatible with the results of the OCAC study based on prediagnosis use, but our results are in contrast to a previous study reporting a substantial reduction in overall mortality among ovarian cancer patients with postdiagnosis aspirin use (Bar et al, 2016). However, besides a small sample size, the latter cohort study was prone to time-related bias which are likely to have influenced the estimates (Chubak et al, 2013).

In our study, we evaluated the influence of low-dose aspirin on mortality after ovarian cancer, assuming that one tablet was equivalent to daily use. Higher dosages of aspirin might be required to obtain a beneficial effect on ovarian cancer prognosis; however, this is not readily supported by analyses of various patterns of low-dose aspirin use in our study, or the similar associations for low-dose (<100 mg) and higher-dose (>100 mg) aspirin in the OCAC study (Dixon et al, 2017). Moreover, for cancer in general, there is no solid evidence that doses of aspirin higher than those used in cardioprotection (75–150 mg) would provide stronger anticancer effects (Coyle et al, 2016; Elwood et al, 2016).

Among the strengths of our study were the nationwide cohort, large study size, high-quality and continuously updated registry data, and complete follow-up. The use of the Danish Prescription Registry ensured complete assessment of prescription drug use. The study design eliminated recall bias, and minimised selection bias and time-related biases.

A limitation of our study was the lack of data on over-the-counter (OTC) purchases of aspirin. However, in Denmark, most (>90%) of the total sales of low-dose aspirin are prescribed (Schmidt et al, 2014), and this proportion may even be higher in cancer patients who are typically under close medical surveillance. High-dose (500 mg) aspirin preparations are mainly sold OTC in Denmark, and thus use of aspirin at this dose may have driven a possible slight inverse association towards the null given that high-dose aspirin is more likely to be used by non-users of low-dose aspirin than among users. However, high-dose aspirin is mainly used for short-term treatment of transient, non-cancer-related pain and therefore OTC use of high-dose aspirin likely resulted in at most minor misclassification of long-term aspirin use. Moreover, the absence of any material differences in associations with increasing dose and cumulative amount of low-dose aspirin indicates that OTC sales of high-dose aspirin likely did not have major impact on our results. Furthermore, in Denmark, regular use of drugs, including high-dose aspirin, is generally prescribed because of at least 50% cost reimbursement and the need for medical surveillance for adverse effects (Schmidt et al, 2014). In our study population, only five patients filled a minimum of one prescription for high-dose aspirin, thus suggesting that use of aspirin at this dose was indeed only sporadical. Still, although we adjusted for several potential confounding factors, residual confounding could have been introduced by lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, smoking and obesity, or other unmeasured factors potentially associated with both low-dose aspirin use and ovarian cancer mortality.

In conclusion, we found no evidence of reduced mortality among ovarian cancer patients associated with postdiagnosis use of low-dose aspirin.

Change history

20 February 2018

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, Harewood R, Spika D, Wang XS, Bannon F, Ahn JV, Johnson CJ, Bonaventure A, Marcos-Gragera R, Stiller C, Azevedo e Silva G, Chen WQ, Ogunbiyi OJ, Rachet B, Soeberg MJ, You H, Matsuda T, Bielska-Lasota M, Storm H, Tucker TC, Coleman MP (2015) Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet 385: 977–1010.

Bar D, Lavie O, Stein N, Feferkorn I, Shai A (2016) The effect of metabolic comorbidities and commonly used drugs on the prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 207: 227–231.

Cho MS, Noh K, Haemmerle M, Li D, Park H, Hu Q, Hisamatsu T, Mitamura T, Mak SLC, Kunapuli S, Ma Q, Sood AK, Afshar-Kharghan V (2017) Role of ADP receptors on platelets in the growth of ovarian cancer. Blood 30 (10): 1235–1242.

Chubak J, Boudreau DM, Wirtz HS, McKnight B, Weiss NS (2013) Threats to validity of nonrandomized studies of postdiagnosis exposures on cancer recurrence and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 105: 1456–1462.

Cooke NM, Spillane CD, Sheils O, O'Leary J, Kenny D (2015) Aspirin and P2Y12 inhibition attenuate platelet-induced ovarian cancer cell invasion. BMC Cancer 15: 627.

Coyle C, Cafferty FH, Langley RE (2016) Aspirin and colorectal cancer prevention and treatment: is it for everyone? Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 12: 27–34.

Dixon SC, Nagle CM, Wentzensen N, Trabert B, Beeghly-Fadiel A, Schildkraut JM, Moysich KB, deFazio A, Risch HA, Rossing MA, Doherty JA, Wicklund KG, Goodman MT, Modugno F, Ness RB, Edwards RP, Jensen A, Kjaer SK, Hogdall E, Berchuck A, Cramer DW, Terry KL, Poole EM, Bandera EV, Paddock LE, Anton-Culver H, Ziogas A, Menon U, Gayther SA, Ramus SJ, Gentry-Maharaj A, Pearce CL, Wu AH, Pike MC, Webb PM (2017) Use of common analgesic medications and ovarian cancer survival: results from a pooled analysis in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Br J Cancer 116: 1223–1228.

Elwood PC, Morgan G, Pickering JE, Galante J, Weightman AL, Morris D, Kelson M, Dolwani S (2016) Aspirin in the treatment of cancer: reductions in metastatic spread and in mortality: a systematic review and meta-analyses of published studies. PLoS One 11: e0152402.

Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509.

Gates MA, Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Hankinson SE (2010) Analgesic use and sex steroid hormone concentrations in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19: 1033–1041.

Hudson AG, Gierach GL, Modugno F, Simpson J, Wilson JW, Evans RW, Vogel VG, Weissfeld JL (2008) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and serum total estradiol in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 680–687.

Minlikeeva AN, Freudenheim JL, Lo-Ciganic WH, Eng KH, Friel G, Diergaarde B, Modugno F, Cannioto R, Gower E, Szender JB, Grzankowski K, Odunsi K, Ness RB, Moysich KB (2015) Use of common analgesics is not associated with ovarian cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24: 1291–1294.

Nagle CM, Ibiebele TI, DeFazio A, Protani MM, Webb PM (2015) Aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen and ovarian cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol 39: 196–199.

R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Online] R Core Team: Vienna, Austria. Available at: https://www.r-project.org/ . Accessed on 1 January 2017.

Schmidt M, Hallas J, Friis S (2014) Potential of prescription registries to capture individual-level use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Denmark: trends in utilization 1999–2012. Clin Epidemiol 6: 155–168.

Therneau T (2015) A Package for Survival Analysis in S, version 2.38 [Online]. Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival . Accessed on 1 January 2017.

Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, Patrono C (2012) The role of aspirin in cancer prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 9: 259–267.

Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Brønnum-Hansen H (2011) Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 39: 12–16.

Umar A, Steele VE, Menter DG, Hawk ET (2016) Mechanisms of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer prevention. Semin Oncol 43: 65–77.

Verdoodt F, Kjaer Hansen M, Kjaer SK, Pottegard A, Friis S, Dehlendorff C (2017a) Statin use and mortality among ovarian cancer patients: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer 141: 279–286.

Verdoodt F, Kjaer SK, Friis S (2017b) Influence of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAID use on ovarian and endometrial cancer: summary of epidemiologic evidence of cancer risk and prognosis. Maturitas 100: 1–7.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 147: 573–577.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Sapere Aude-program of the Danish Council for Independent Research (Det Frie Forskningsråd Sapere Aude-program, project No. 6110-00596B), and the Mermaid project (Mermaid III).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Verdoodt, F., Kjaer, S., Dehlendorff, C. et al. Aspirin use and ovarian cancer mortality in a Danish nationwide cohort study. Br J Cancer 118, 611–615 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.449

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.449