Abstract

Background:

The Mullerian ducts are the embryological precursors of the female reproductive tract, including the uterus; anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) has a key role in the regulation of foetal sexual differentiation. Anti-Mullerian hormone inhibits endometrial tumour growth in experimental models by stimulating apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. To date, there are no prospective epidemiologic data on circulating AMH and endometrial cancer risk.

Methods:

We investigated this association among women premenopausal at blood collection in a multicohort study including participants from eight studies located in the United States, Europe, and China. We identified 329 endometrial cancer cases and 339 matched controls. Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in blood were quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) across tertiles and for a doubling of AMH concentrations (ORlog2). Subgroup analyses were performed by ages at blood donation and diagnosis, oral contraceptive use, and tumour characteristics.

Results:

Anti-Mullerian hormone was not associated with the risk of endometrial cancer overall (ORlog2: 1.07 (0.99–1.17)), or with any of the examined subgroups.

Conclusions:

Although experimental models implicate AMH in endometrial cancer growth inhibition, our findings do not support a role for circulating AMH in the aetiology of endometrial cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In early gestation, male and female embryos have both Wolffian ducts, which subsequently develop into the male genital tracts in the male fetus, and Mullerian ducts, which develop into the uterus, the fallopian tubes, and the upper vagina in female fetus (Sobel et al, 2004). The anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), also known as the Mullerian-inhibiting substance (MIS), is secreted by the Sertoli cells of the testes and is responsible for the regression of the Mullerian ducts during foetal life in males (MacLaughlin and Donahoe, 2010). In female fetuses, absence of AMH production during this period allows development of the female genital tracts from the Mullerian ducts.

In females, AMH is secreted by the granulosa cells of the growing ovarian follicles and serves as a sensitive marker of ovarian reserve; its concentrations are very low at birth, increase significantly at puberty, remain stable thereafter until age ∼25 years, and then slowly decline to be undetectable at the onset of menopause, when the ovarian follicle pool is exhausted (Dewailly et al, 2014). The clinical use of AMH is well established. In females, serum AMH is utilised for monitoring patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumours, with up to 90% of cases presenting with high AMH concentrations (Geerts et al, 2009), and AMH concentrations can be predictive of ovarian response after in vitro fertilisation treatments (Fleming et al, 2015). Further, AMH is under discussion to become a diagnostic criterion for patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), as AMH levels are two to four times higher in women with PCOS as compared with healthy women (Garg and Tal, 2016).

Anti-Mullerian hormone activates downstream pathways notable for differentiation and growth inhibition by binding to its specific type II receptor (AMHRII), and in vitro experimental models have shown that AMH inhibits endometrial cancer growth by apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in AMHRII-positive endometrial cancer cell lines (Kim et al, 2014). Renaud et al (2005) provided the first evidence for a potential inhibitory effect of AMH in endometrial cancer, showing that AMH inhibits endometrial cancer growth by apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in AMHRII-positive endometrial cancer cell lines.

In 2012, endometrial cancer, also referred to as cancer of the corpus uteri, was predicted to be diagnosed in more than 47 000 women in the United States (Siegel et al, 2012) with more than 300 000 incident cases worldwide (Ferlay et al, 2014). Although this cancer is frequently diagnosed when still localised, ∼30% of cases are diagnosed at more advanced stages (regional/distant; Howlader et al, 2017) according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the National Cancer Institute. Established risk factors for endometrial cancer are obesity and use of exogenous oestrogen after menopause; however, these factors can only explain about half of the endometrial cancer cases in Western countries (Arnold et al, 2015).

To date, there are no prospective epidemiologic data on the association between AMH and risk of endometrial cancer. However, given experimental data, we hypothesised that higher circulating AMH levels may confer a relative protection against the development of endometrial cancer. We investigated this hypothesis in a nested case–control study including premenopausal women from cohort studies within the Prospective Study of AMH and Gynecologic Cancer Risk.

Materials and methods

Study population

This nested case–control study included participants from eight prospective cohort studies located in the United States, Europe, and China. The following studies contributed to this investigation: Columbia, Missouri Serum Bank (USA; Dorgan et al, 2009), the Campaign Against Cancer and Heart Disease (CLUE I/II; USA; McSorley et al, 2007), the New York University Women’s Health Study (NYUWHS; USA; Clendenen et al, 2016), the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC; Europe; Dossus et al, 2010), the Guernsey Cohort Study (UK; Wang et al, 2014), the Hormones and Diet in the Etiology of Breast Cancer (ORDET; Italy; Clendenen et al, 2016), the Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study (NSHDS; Sweden; Clendenen et al, 2016), and the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS; China; Dorjgochoo et al, 2009).

In each of the cohort studies, blood samples were collected using standardised protocols. Samples were stored at ⩽−70 oC in all studies except the Guernsey study; samples from this study were stored at −20 °C. Detailed information on each of the contributing cohorts is provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the collaborating institutions and the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA. All participants provided informed consent.

Ascertainment of cases

Our investigation was limited to premenopausal participants, who were younger than 47 years at blood collection, as AMH concentrations decline with age and are undetectable after menopause. Cases included women diagnosed with incident, primary endometrial cancer ascertained by self-report with medical record confirmation and/or linkages to cancer registries. All cases had no history of cancer, with the possible exception of non-melanoma skin cancer, before the diagnosis of endometrial cancer and did not report prior hysterectomy. Tumour characteristics (i.e., histology, stage, and grade) were obtained from cancer registries, pathology reports, and medical records. We identified a total of 329 eligible endometrial cancer cases diagnosed after blood collection. Six of these cases were diagnosed with synchronous ovarian cancer (none of which were of granulosa tumours); these cases were excluded in sensitivity analyses.

Control selection

Eligible controls were premenopausal women younger than 47 years at blood collection and were cancer-free (except non-melanoma skin cancer) and not reporting prior hysterectomy at the index date of their matched case. For every cohort, except NSHDS, one control was matched to each case; NSHDS matched up to two controls per case. All studies matched cases and controls on age and date at blood collection; additional matching factors specific to each cohort included study centre, time of day at blood collection, fasting status, and menstrual cycle phase (matching factors by study provided in Supplementary Table 1). A total of 339 matched controls were identified.

Participating cohorts contributed between 10 cases/10 controls (Columbia Serum Bank) to 102 cases/102 controls (CLUEI/II; Table 1).

Case characteristics

Histology data were available for 309 cases (94%). The majority of cases were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS; n=166, 54%), followed by endometrioid tumours (n=96, 31%) and others (n=47, 15%; e.g., serous (n=10), mucinous (n=6)). The majority of cases had data on stage (n=227; 69%) and grade (n=219; 67%) at diagnosis. Well-differentiated tumours (i.e., grade 1) were classified as ‘low grade’ (n=118; 54%), whereas moderately and poorly/undifferentiated tumours (i.e., grades 2 and 3) were classified as ‘high grade’ (n=101; 46%). Data on histology and grade were used to classify 82% of tumours into Type I and Type II. We classified endometrioid adenocarcinoma (ICD-O-2 codes: 8380, 8381, 8382, and 8383) with grades 1 and 2, adenocarcinoma NOS (8140), and adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (8560, 8570) as Type I (90%, n=242), and endometrioid adenocarcinoma with grade 3, serous/papillary serous (8441, 8460, 8461) and mixed cell adenocarcinoma (8323) as type II tumours (Setiawan et al, 2013).

Covariate data

Each participating cohort provided data on covariates; these data were collected at the time of blood collection and were centrally collated and harmonised. Information on demographics, lifestyle, reproductive history, and medical history was obtained via self-report and interview (Supplementary Table 1).

Laboratory assays – AMH

Blood samples from each cohort were sent to a single laboratory at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) for AMH assays. This investigation used serum or plasma samples, depending on sample availability. Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in paired serum and plasma samples from the same individuals are highly correlated (r⩾0.98; Merhi et al, 2008) and we observed no difference in the mean AMH concentrations among participants with serum or plasma in the two studies that provided samples in both matrices (CLUEI/II: P=0.84; EPIC: P=0.88). Further, matrix (serum or plasma) was the same for each case and her matched control. Specimens of individually matched case and control subjects were always included in the same laboratory batch, alongside blinded quality-control samples. The technicians performing the assays were blinded to the case, control, or quality-control status of the specimens. Concentrations of AMH were measured using a commercially available picoAMH enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Ansh Catalog no. AL-124, Webster, TX, USA); the assay limit of detection was 0.02 ng ml−1. The overall coefficient of variation for AMH based on the study blinded pooled quality-control samples was 13.9%.

Laboratory assays – androgens and sex hormone-binding globulin

Androgens were measured for assessment as potential confounders. Where available, we used existing data on testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). These data were available from previous studies for at least a subset of participants in four of the participating cohorts (CLUE, EPIC, NYUWHS, and NSHDS; n=193, 29%). Laboratory methods for these measurements are provided in Supplementary Table 1. For participants without existing data on androgens or SHBG, participating cohorts were asked to provide additional serum (or plasma) volume for these assays. Samples from 235 participants from the Columbia, EPIC, Guernsey, NYUWHS, and ORDET cohorts were centrally assayed at the laboratory of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ; Heidelberg, Germany). Direct radioimmunoassays (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) were used to measure testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEAS. SHBG was measured using an immunoradiometric assay (Cis-Bio, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). The overall coefficients of variation for samples assayed at DKFZ were <22% for all androgens and 21% for SHBG.

Statistical analyses

Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations were log2-transformed to normalise the distribution; this transformation also allows an estimation of the effect of a doubling of AMH (i.e., one-unit increase in log2-transformed AMH corresponds to a doubling). The extreme Studentised deviate many-outlier procedure was used to identify outliers (Rosner, 1983); no outliers were identified. Tertiles of AMH were defined using the study-specific distribution in controls; P for trend was calculated using tertile medians. Given that age is a very strong determinant of AMH concentrations, cases and controls were matched on age at blood draw and in addition all models were adjusted for age. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) across tertiles of AMH concentrations and for a doubling of AMH concentrations (ORlog2).

To assess between-study heterogeneity, we used a random effects model as proposed by DerSimonian and Laird (1986); we observed no significant between-study heterogeneity. Therefore, we present results based on the pooled participant data.

We evaluated the effect of potential confounders (i.e., age at menarche (continuous, 25% missing), body mass index (BMI; continuous, 21% missing), ever use of oral contraceptives (OC; no, yes, 23% missing), total number of pregnancies (0, 1, 2, 3, ⩾4; 27% missing), smoking status (never, past, current; 4% missing)) using multiple imputations with 10 imputed data sets and adjusted OR estimates calculated in each of the multiple-imputed data sets and pooled using Rubin’s rule (Raghunathan et al, 2010). None of the potential confounders were retained in the final models since effect estimates were not influenced by statistical adjustment (<10% change after adjustment), and statistical significance of the observed associations was not affected.

Data on circulating androgen concentrations were available for 221 cases and 207 controls (64%). Adjustments for androgens or SHBG in subjects with available data had a negligible effect on risk estimates (<10% change after adjustment), and thus these markers were not retained in the final models.

Polytomous conditional logistic regression models were used to examine heterogeneity of associations between AMH concentrations and endometrial cancer by subtype defined by tumour-related characteristics (e.g., histology and age at diagnosis). Statistical heterogeneity of associations in stratified analyses was assessed via a likelihood ratio test comparing a model allowing the association for the risk factor of interest to vary by subgroup vs one assuming the same association (Wang et al, 2016). We evaluated heterogeneity by oral contraceptive use and age at blood draw by including a multiplicative interaction term in the models and evaluating the Wald P-value.

We conducted sensitivity analyses excluding women diagnosed at ⩽1 or ⩽2 years after blood donation to evaluate any effect of subclinical endometrial cancer on AMH concentrations, as well as the exclusion of women with synchronous ovarian cancer. Further sensitivity analyses excluded current OC users, as AMH levels are lower in current users compared with former or never users (Dolleman et al, 2013).

Given the final sample size of 329 cases and 339 controls, this study had statistical power to detect an OR of 0.61 or 1.64 with 80% power and 95% confidence when examining tertiles. This uses the observed within-matched pair correlation of MIS levels of 0.16. The study was slightly better powered than the protocol-specified detectable effect of 0.56 or 1.80, which had anticipated 342 matched pairs but also a larger within-matched pair correlation that would have reduced power. The study was also able to detect an ORlog2 of 0.87 or 1.15 for a one-unit change in log2-transformed AMH for endometrial cancer overall based on the observed log-2 transformed AMH s.d. of 2.26. Statistical power was more limited in small subgroups (e.g., type II disease (n=28 cases), 80% power, 95% confidence, and minimum detectable ORlog2 of 0.63 or 1.60).

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analyses System (SAS) software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

The median age at blood draw in the study population was 41.5 years, ranging from 38 years in Guernsey and CLUE to 44 years in SWHS (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Relative to controls, cases had a somewhat higher median BMI (kg m−2; cases: 24.8; controls: 23.7), a higher percentage was nulliparous (cases: 25%; controls: 20%), and a lower percentage reported ever OC use (cases: 46%; controls: 56%). The median age at diagnosis was 54 years and a median of 12 years elapsed between blood draw and diagnosis. As expected, AMH was inversely correlated with age at blood collection (Spearman: rcases=−0.50, rcontrols=−0.43, both P<0.01). Weak correlations were observed between androgens and SHBG and AMH (Spearman: rcases=−0.27 (SHBG) to 0.19 (testosterone), rcontrols=−0.03 (DHEAS) to 0.15 (testosterone)).

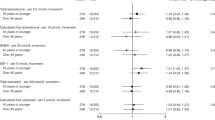

We observed no significant association between AMH and risk of endometrial cancer overall (ORlog2=1.07 [0.99–1.17]), and results from the pooled individual-level data were similar to those from the meta-analysis (ORlog2, meta-analysis=1.05 [0.97–1.15]; Phet=0.46; Figure 1). Similarly, we observed no association comparing extreme tertiles (OR T3vs.T1=1.29 [0.82–2.03]; Table 3).

Results did not significantly differ by disease subtype (e.g., by histology, Phet=0.86, endometrioid, ORT3vs.T1=1.12 [0.49–2.57], Ptrend=0.46; adenocarcinoma, NOS, OR T3vs.T1=1.47 [0.78–2.75], Ptrend=0.08; Table 3), age at blood donation (Phet=0.13), or ever OC use (Phet=0.85). In analyses stratified by cancer-related characteristics, we observed no heterogeneity by age at diagnosis (Phet=0.77), time between blood donation and diagnosis (Phet=0.81), tumour grade (Phet=0.68), stage (Phet=0.53), or Type I/II classification (Phet=0.70).

Results were similar when restricting analyses to women not using oral contraceptives at blood collection (n=291 sets; ORT3 vs. T1=1.19 [0.73–1.93], Ptrend=0.15; ORlog2=1.06 [0.98–1.16]), or to women diagnosed more than 1 year after blood draw (n=323 sets) or 2 years after blood draw (n=315 sets; data not shown). Exclusion of the six cases with synchronous ovarian cancer did not have an impact on the observed effect estimates.

Discussion

We conducted a world-wide collaborative investigation, including eight prospective cohort studies, and present the first data on pre-diagnosis AMH concentrations and subsequent risk of endometrial cancer. We observed no association between AMH concentrations and risk of endometrial cancer overall, or in analyses stratified by age at blood draw, oral contraceptive use, or cancer-related characteristics.

To date, evidence for an involvement of AMH in the development of endometrial cancer risk comes from experimental models (reviewed in Kim et al (2014)). Experimental data have shown that AMH inhibits growth of human endometrial cancer cell lines that express the AMHRII by causing cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase and inducing apoptosis. Anti-Mullerian hormone regulates the proteins p107 and p130, responsible for G1-to-S phase transition and cell cycle exit, respectively, as well as the transcription factor E2F1, which leads to decreased cell division (Renaud et al, 2005). It should be noted that the concentrations used in these experimental models were reported to be double the dose required to induce Mullerian duct regression in culture (Renaud et al, 2005). Similar inhibitory effects have been observed in experimental models of endometrial stromal cells (Wang et al, 2009) and of endometriosis (reviewed in Kim et al (2014); Signorile et al (2014)). In terms of epidemiologic data, prior studies have noted lower AMH concentrations among women with endometriosis, although findings to date are somewhat inconsistent (reviewed in Sanchez et al (2016)), and one previous retrospective case–control study observed no difference in circulating AMH concentrations between endometrial cancer cases and controls (Dogan et al, 2015). In terms of another gynaecologic cancer, experimental data support a role for AMH in the inhibition of epithelial ovarian cancer growth and proliferation (Donahoe et al, 1981; Chin et al, 1991; Kim et al, 1992; Stephen et al, 2002; Chang et al, 2011; Park et al, 2017), although epidemiologic data on AMH and epithelial ovarian cancer are limited (Schock et al, 2014). With respect to non-epithelial ovarian cancers, AMH is a marker for ovarian adult granulosa cell tumours (Geerts et al, 2009; Farkkila et al, 2015; Haltia et al, 2017). Epidemiologic studies to date consistently support a positive association between circulating AMH concentrations and breast cancer risk (Dorgan et al, 2009; Nichols et al, 2015; Eliassen et al, 2016). Our findings of a suggestive positive trend for endometrial cancer overall are in line with these observations for breast cancer.

A possible explanation for the lack of association in our study is the hypothesised AMH autocrine/paracrine system in the adult endometrium (Wang et al, 2009); it is plausible that circulating concentrations do not reflect AMH concentrations or activity in the endometrium, and thus do not exert an endocrine effect. This is supported by one study among 55 patients with endometriosis and 45 healthy women that observed that circulating AMH concentrations were unaffected by higher AMH mRNA and protein expression in endometriosis lesions (Carrarelli et al, 2014). Further support for a paracrine effect of AMH comes from the observation that AMH secreted by each testis, in genetically male embryos, induces regression of only the ipsilateral Mullerian duct (Behringer, 1995).

Strengths of our study include its prospective design, and relatively large sample size, given AMH can only be measured before the menopause. Individual-level data on study subjects were uniformly harmonised, standardising covariate categorisation for the statistical analysis, and all AMH assays were performed in a single laboratory using an ultrasensitive AMH assay that is valid and reproducible (Welsh et al, 2014; Burks et al, 2015). A limitation of our study is that only one AMH measurement was obtained. However, the intraclass correlation of AMH concentrations over 1 year is high (r=0.87; Dorgan et al, 2010), and AMH concentrations track well over time in the same woman before menopause (r=0.66 for two measurements 4 years apart; van Rooij et al, 2005); thus, any misclassification of AMH concentrations is likely to be small. All cases included in this study were diagnosed with incident, primary endometrial cancer and six of these cases were diagnosed with synchronous ovarian cancer; none of the cases included in this study had synchronous ovarian granulosa cell tumours, which would have caused elevated AMH concentrations. Exclusion of the six cases with synchronous ovarian cancer did not have an impact on the observed effect estimates. Samples utilised in this study were from established biorepositories, and have been in storage for up to decades. However, no association between storage time and AMH concentrations was observed in our previous cross-sectional study (Jung et al, 2017). Finally, the median age at diagnosis in this study was 54 years; this is younger than the median age at diagnosis in the population at large (e.g., median age at diagnosis in the United States: 62 years) (Howlader et al, 2017). It is plausible that the results observed here for endometrial cancer with younger age at diagnosis are not generalisable to women with later disease onset.

Anti-Mullerian hormone has been proposed as a potential treatment for endometrial cancers (Kim et al, 2014). However, although experimental models demonstrate an inhibiting effect of AMH on endometrial cancer growth, our findings in premenopausal women do not support a role for circulating AMH concentrations in the aetiology of endometrial cancer.

Change history

26 October 2017

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan AG, Stevens GA, Ezzati M, Ferlay J, Miranda JJ, Romieu I, Dikshit R, Forman D, Soerjomataram I (2015) Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 16 (1): 36–46.

Behringer RR (1995) The mullerian inhibitor and mammalian sexual development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 350 (1333): 285–288, discussion 289.

Burks HR, Ross L, Opper N, Paulson E, Stanczyk FZ, Chung K (2015) Can highly sensitive antimullerian hormone testing predict failed response to ovarian stimulation? Fertil Steril 104 (3): 643–648.

Carrarelli P, Rocha AL, Belmonte G, Zupi E, Abrao MS, Arcuri F, Piomboni P, Petraglia F (2014) Increased expression of antimullerian hormone and its receptor in endometriosis. Fertil Steril 101 (5): 1353–1358.

Chang HL, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Nicolaou F, Li X, Wei X, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK (2011) Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits invasion and migration of epithelial cancer cell lines. Gynecol Oncol 120 (1): 128–134.

Chin TW, Parry RL, Donahoe PK (1991) Human mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 51 (8): 2101–2106.

Clendenen TV, Hertzmark K, Koenig KL, Lundin E, Rinaldi S, Johnson T, Krogh V, Hallmans G, Idahl A, Lukanova A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A (2016) Premenopausal circulating androgens and risk of endometrial cancer: results of a prospective study. Horm Cancer 7 (3): 178–187.

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7 (3): 177–188.

Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R, Griesinger G, Kelsey TW, La Marca A, Lambalk C, Mason H, Nelson SM, Visser JA, Wallace WH, Anderson RA (2014) The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update 20 (3): 370–385.

Dogan NU, Kerimoglu OS, Karabagli P, Pekin A, Yilmaz SA, Incesu F, Celik C (2015) Anti-Mullerian hormone is associated with extrauterine involvement and stage of disease in patients with endometrial cancer. J Obstetr 35 (2): 178–182.

Dolleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dolle ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ, van der Schouw YT (2013) Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Mullerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 (5): 2106–2115.

Donahoe PK, Fuller AF Jr ., Scully RE, Guy SR, Budzik GP (1981) Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits growth of a human ovarian cancer in nude mice. Ann Surg 194 (4): 472–480.

Dorgan JF, Spittle CS, Egleston BL, Shaw CM, Kahle LL, Brinton LA (2010) Assay reproducibility and within-person variation of Mullerian inhibiting substance. Fertil Steril 94 (1): 301–304.

Dorgan JF, Stanczyk FZ, Egleston BL, Kahle LL, Shaw CM, Spittle CS, Godwin AK, Brinton LA (2009) Prospective case-control study of serum mullerian inhibiting substance and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (21): 1501–1509.

Dorjgochoo T, Gao YT, Chow WH, Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Cai Q, Rothman N, Cai H, Franke AA, Zheng W, Dai Q (2009) Plasma carotenoids, tocopherols, retinol and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women Health Study (SWHS). Breast Cancer Res Treat 117 (2): 381–389.

Dossus L, Rinaldi S, Becker S, Lukanova A, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Stegger J, Overvad K, Chabbert-Buffet N, Jimenez-Corona A, Clavel-Chapelon F, Rohrmann S, Teucher B, Boeing H, Schutze M, Trichopoulou A, Benetou V, Lagiou P, Palli D, Berrino F, Panico S, Tumino R, Sacerdote C, Redondo ML, Travier N, Sanchez MJ, Altzibar JM, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Duijnhoven FJ, Onland-Moret NC, Peeters PH, Hallmans G, Lundin E, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Allen N, Key TJ, Slimani N, Hainaut P, Romaguera D, Norat T, Riboli E, Kaaks R (2010) Obesity, inflammatory markers, and endometrial cancer risk: a prospective case-control study. Endocr Relat Cancer 17 (4): 1007–1019.

Eliassen AH, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Rosner B, Hankinson SE (2016) Plasma anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women in the nurses' health studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 25 (5): 854–860.

Farkkila A, Koskela S, Bryk S, Alfthan H, Butzow R, Leminen A, Puistola U, Tapanainen JS, Heikinheimo M, Anttonen M, Unkila-Kallio L (2015) The clinical utility of serum anti-Mullerian hormone in the follow-up of ovarian adult-type granulosa cell tumors—a comparative study with inhibin B. Int J Cancer 137 (7): 1661–1671.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F (2014) Globocan 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO: Lyon, France. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr. (Accessed on 20/03/2017).

Fleming R, Seifer DB, Frattarelli JL, Ruman J (2015) Assessing ovarian response: antral follicle count versus anti-Mullerian hormone. Reprod Biomed Online 31 (4): 486–496.

Garg D, Tal R (2016) The role of AMH in the pathophysiology of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Reprod Biomed Online 33 (1): 15–28.

Geerts I, Vergote I, Neven P, Billen J (2009) The role of inhibins B and antimullerian hormone for diagnosis and follow-up of granulosa cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19 (5): 847–855.

Haltia UM, Hallamaa M, Tapper J, Hynninen J, Alfthan H, Kalra B, Ritvos O, Heikinheimo M, Unkila-Kallio L, Perheentupa A, Farkkila A (2017) Roles of human epididymis protein 4, carbohydrate antigen 125, inhibin B and anti-Mullerian hormone in the differential diagnosis and follow-up of ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol 144 (1): 83–89.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (2017) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014. Based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/.

Jung S, Allen N, Arslan AA, Baglietto L, Brinton LA, Egleston BL, Falk R, Fortner RT, Helzlsouer KJ, Idahl A, Kaaks R, Lundin E, Merritt M, Onland-Moret C, Rinaldi S, Sanchez MJ, Sieri S, Schock H, Shu XO, Sluss PM, Staats PN, Travis RC, Tjonneland A, Trichopoulou A, Tworoger S, Visvanathan K, Krogh V, Weiderpass E, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Zheng W, Dorgan JF (2017) Demographic, lifestyle, and other factors in relation to antimullerian hormone levels in mostly late premenopausal women. Fertil Steril 107 (4): 1012–1022 e2.

Kim JH, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK (2014) Mullerian inhibiting substance/anti-Mullerian hormone: a novel treatment for gynecologic tumors. Obstetr Gynecol Sci 57 (5): 343–357.

Kim JH, Seibel MM, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK, Ransil BJ, Hametz PA, Richards CJ (1992) The inhibitory effects of mullerian-inhibiting substance on epidermal growth factor induced proliferation and progesterone production of human granulosa-luteal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75 (3): 911–917.

MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK (2010) Mullerian inhibiting substance/anti-Mullerian hormone: a potential therapeutic agent for human ovarian and other cancers. Future Oncol 6 (3): 391–405.

McSorley MA, Alberg AJ, Allen DS, Allen NE, Brinton LA, Dorgan JF, Pollak M, Tao Y, Helzlsouer KJ (2007) C-reactive protein concentrations and subsequent ovarian cancer risk. Obstetr Gynecol 109 (4): 933–941.

Merhi ZO, Messerlian GM, Minkoff H, Eklund EE, Macura J, Feldman J, Rodriguez C, Seifer DB (2008) Comparison of serum and plasma measurements of Mullerian inhibiting substance. Fertil Steril 89 (6): 1836–1837.

Nichols HB, Baird DD, Stanczyk FZ, Steiner AZ, Troester MA, Whitworth KW, Sandler DP (2015) Anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations in premenopausal women and breast cancer risk. Cancer Prev Res 8 (6): 528–534.

Park SH, Chung YJ, Song JY, Kim SI, Pepin D, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK, Kim JH (2017) Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits an ovarian cancer cell line via beta-catenin interacting protein deregulation of the Wnt signal pathway. Int J Oncol 50 (3): 1022–1028.

Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P (2010) A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol 27: 85–95.

Renaud EJ, MacLaughlin DT, Oliva E, Rueda BR, Donahoe PK (2005) Endometrial cancer is a receptor-mediated target for mullerian inhibiting substance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 (1): 111–116.

Rosner B (1983) Percentage points for a generalized ESD many-outlier procedure. Technometrics 25 (2): 165–172.

Sanchez AM, Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Pagliardini L, Candiani M, Vigano P (2016) Endometriosis as a detrimental condition for granulosa cell steroidogenesis and development: From molecular alterations to clinical impact. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 155 (Pt A): 35–46.

Schock H, Lundin E, Vaarasmaki M, Grankvist K, Fry A, Dorgan JF, Pukkala E, Lehtinen M, Surcel HM, Lukanova A (2014) Anti-Mullerian hormone and risk of invasive serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 25 (5): 583–589.

Setiawan VW, Yang HP, Pike MC, McCann SE, Yu H, Xiang YB, Wolk A, Wentzensen N, Weiss NS, Webb PM, van den Brandt PA, van de Vijver K, Thompson PJ, Group TANECS, Strom BL, Spurdle AB, Soslow RA, Shu XO, Schairer C, Sacerdote C, Rohan TE, Robien K, Risch HA, Ricceri F, Rebbeck TR, Rastogi R, Prescott J, Polidoro S, Park Y, Olson SH, Moysich KB, Miller AB, McCullough ML, Matsuno RK, Magliocco AM, Lurie G, Lu L, Lissowska J, Liang X, Lacey JV, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankinson SE, Hakansson N, Goodman MT, Gaudet MM, Garcia-Closas M, Friedenreich CM, Freudenheim JL, Doherty J, De Vivo I, Courneya KS, Cook LS, Chen C, Cerhan JR, Cai H, Brinton LA, Bernstein L, Anderson KE, Anton-Culver H, Schouten LJ, Horn-Ross PL (2013) Type I and II Endometrial Cancers: Have They Different Risk Factors? J Clin Oncol 31 (20): 2607–2618.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62 (1): 10–29.

Signorile PG, Petraglia F, Baldi A (2014) Anti-mullerian hormone is expressed by endometriosis tissues and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in endometriosis cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 33: 46.

Sobel V, Zhu YS, Imperato-McGinley J (2004) Fetal hormones and sexual differentiation. Obstetr Gynecol Clin N Am 31 (4): 837–856, x-xi.

Stephen AE, Pearsall LA, Christian BP, Donahoe PK, Vacanti JP, MacLaughlin DT (2002) Highly purified mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits human ovarian cancer in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 8 (8): 2640–2646.

van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, Scheffer GJ, Looman CW, Habbema JD, de Jong FH, Fauser BJ, Themmen AP, te Velde ER (2005) Serum antimullerian hormone levels best reflect the reproductive decline with age in normal women with proven fertility: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril 83 (4): 979–987.

Wang J, Dicken C, Lustbader JW, Tortoriello DV (2009) Evidence for a Mullerian-inhibiting substance autocrine/paracrine system in adult human endometrium. Fertil Steril 91 (4): 1195–1203.

Wang M, Spiegelman D, Kuchiba A, Lochhead P, Kim S, Chan AT, Poole EM, Tamimi R, Tworoger SS, Giovannucci E, Rosner B, Ogino S (2016) Statistical methods for studying disease subtype heterogeneity. Stat Med 35 (5): 782–800.

Wang XS, Tipper S, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Key TJ, Travis RC (2014) First-morning urinary melatonin and breast cancer risk in the Guernsey Study. Am J Epidemiol 179 (5): 584–593.

Welsh P, Smith K, Nelson SM (2014) A single-centre evaluation of two new anti-Mullerian hormone assays and comparison with the current clinical standard assay. Hum Reprod 29 (5): 1035–1041.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 CA163018 to JF Dorgan. RT Fortner was supported by a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship of the European Commission's Seventh Framework Programme (MC-IIF-623984). Cancer incidence data for CLUE were provided by the Maryland Cancer Registry, Center for Cancer Surveillance and Control, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 201W. Preston Street, Room 400, Baltimore, MD 21201, http://phpa.dhmh.maryland.gov/cancer, 410–767–4055. We acknowledge the State of Maryland, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund, and the National Program of Cancer Registries of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the funds that support the collection and availability of the cancer registry data. The NYU Women’s Health Study is supported by grants R01 CA178949, CA098661, UM1 CA182934, and centre grants P30 CA016087 and P30 ES000260. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study is supported by NIH grants R37 CA070867 and UM1 CA182910. The coordination of EPIC is financially supported by the European Commission (DG-SANCO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The national cohorts are supported by Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM; France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Deutsche Krebshilfe, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, and Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Germany); the Hellenic Health Foundation (Greece); Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro-AIRC-Italy and National Research Council (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Statistics Netherlands (the Netherlands); ERC-2009-AdG 232997 and Nordforsk, Nordic Centre of Excellence programme on Food, Nutrition and Health (Norway); Health Research Fund (FIS), PI13/00061 to Granada; PI13/01162 to EPIC-Murcia, Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, ISCIII RETIC (RD06/0020; Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council and County Councils of Skåne and Västerbotten (Sweden); Cancer Research UK (14136 to EPIC-Norfolk; C570/A16491 and C8221/A19170 to EPIC-Oxford), Medical Research Council (1000143 to EPIC-Norfolk, MR/M012190/1 to EPIC-Oxford; UK).

Disclaimer

The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Data sharing

For information on how to submit an application for gaining access to EPIC data and/or biospecimens, please follow the instructions at http://epic.iarc.fr/access/index.php.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fortner, R., Schock, H., Jung, S. et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone and endometrial cancer: a multi-cohort study. Br J Cancer 117, 1412–1418 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.299

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.299

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

BMP signaling in cancer stemness and differentiation

Cell Regeneration (2023)

-

The association between the levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and dietary intake in Iranian women

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2021)