Abstract

Background:

Tubal ligation is known to be associated with a reduction in ovarian cancer risk. Associations with breast, endometrial and cervical cancers have been suggested. We investigated associations for 26 site-specific cancers in a large UK cohort.

Methods:

Study participants completed a questionnaire on reproductive and lifestyle factors in 1996–2001, and were followed for cancer and death via national registries. Using Cox regression models, we estimated adjusted relative risks (RRs) for 26 site-specific cancers among women with vs without tubal ligation.

Results:

In 1 278 783 women without previous cancer, 167 430 incident cancers accrued during 13.8 years’ follow-up. Significantly reduced risks were found in women with tubal ligation for cancers of the ovary (RR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.76–0.85; P<0.001; n=8035), peritoneum (RR=0.81, 0.66–0.98; P=0.03; n=730), and fallopian tube (RR=0.60, 0.37–0.96; P=0.04; n=168). No significant associations were found for endometrial, breast, or cervical cancers.

Conclusions:

The reduced risks of ovarian, peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers are consistent with hypotheses of a common origin for many tumours at these sites, and with the suggestion that tubal ligation blocks cells, carcinogens or other agents from reaching the ovary, fallopian tubes and peritoneal cavity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Tubal ligation (female sterilisation) is known to be associated with a reduced risk of ovarian cancer (Sieh et al, 2013). Reports of associations with other cancers have varied. In particular, several investigators have described associations with breast (Irwin et al, 1988; Kreiger et al, 1999), endometrial (Kjaer et al, 2004), cervical (Mathews et al, 2012) and anal cancers (Coffey et al, 2015). We report here the associations between tubal ligation and risk of 26 site-specific cancers in a large cohort of UK women.

Materials and Methods

Study design, data collection and follow-up

The Million Women Study is a prospective study of 1.3 million UK women, recruited in 1996–2001. Participants completed a questionnaire at recruitment, on socio-demographic, reproductive and lifestyle factors. Information on tubal ligation came from responses to the question ‘Have you been sterilised (had your tubes tied)?’ on the recruitment questionnaire. The study design and methods have been described previously (The Million Women Study Collaborative Group, 1999; Million Women Study Collaborators, 2003) and questionnaires can be viewed online at http://www.millionwomenstudy.org.

Follow-up for outcomes was based on routine registers: participants have been flagged on the NHS Central Register for cancer registrations and deaths. Information on cancer provided to investigators includes the date of registration and cancer site (coded using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 1992). All participants gave written consent to follow-up at recruitment. Ethical approval was granted by the Oxford and Anglia Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC 97/01).

Statistical analysis

Women were excluded from the analyses if they had invasive cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer (ICD-10 code C44) before recruitment (n=66 221 (5%)), or missing data on tubal ligation (n=40 612 (3%)). The remaining women (n=1 278 783) contributed person-years from the date of recruitment until the earliest of the date of registration of any cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer), the date of death, or last date of follow-up (31st December 2013). About 1% of participants were lost to follow-up and contributed person-years until the date they were lost.

Cox (proportional hazards) regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (referred to as relative risks (RRs)) of developing a given cancer by tubal ligation status. Attained age was the underlying time variable. Analyses were run separately for each of 26 cancer types or sites, defined by ICD-10 code, and for all cancer (any invasive cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer, ICD-10 C44). Analyses were limited to cancer types for which 500 or more cases with an identified primary site had accrued. In addition, we conducted an analysis for fallopian tube cancers (ICD-10 C57.0), despite having fewer than 500 cases, as there is a reasonable prior hypothesis that surgery to the fallopian tube might affect the incidence of cancer at this site.

All analyses were stratified by geographical region (10 regions corresponding to the areas covered by the cancer registries) and quintiles of socioeconomic status (based on the Townsend deprivation index) (Townsend et al, 1988), and additionally adjusted for parity (0, 1, 2, 3+), age at first birth (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30+), smoking (never, past, current <10 cigarettes/day, current 10–19 cigarettes/day, current 20+ cigarettes/day), average alcohol intake per week (none, ⩽7 units, >7 & ⩽14 units, >14 units), frequency of strenuous exercise (

All adjustment variables were as reported at recruitment. For adjustment and stratification variables, missing values were assigned to a separate category. Exposure information was either missing or reported as unknown for ⩽6% of women for all potential confounders. Analyses of ovarian cancer risk were restricted to women without bilateral oophorectomy; those of endometrial and cervical cancer were restricted to women without hysterectomy; those of fallopian tube cancer were restricted to women without either bilateral oophorectomy or hysterectomy (as the fallopian tubes might potentially be removed as part of either surgery). Analyses were performed in Stata-14 (StataCorp, 2015). Figures were drawn in R (R Development Core Team, 2015) using Matthew Arnold’s ‘Jasper’ package (Arnold, 2015).

Results

The study population included 1 278 783 women without prior cancer, average age 56.1 (s.d. 4.9) at recruitment, 23% of whom reported a tubal ligation, at an average age of 34.5 (s.d. 5.3). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the cohort. A total of 167 430 cancers accrued, after a mean follow-up of 13.8 years (s.d. 3.4). The average age at cancer diagnosis was 65.6 years (s.d. 6.5). There was no association between tubal ligation and risk of all cancers combined (RR=1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.98–1.01).

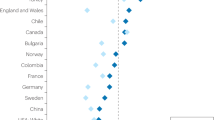

Figure 1 displays adjusted RRs and 95% CIs of 26 site- or type-specific cancers among women with vs without tubal ligation. There was a 20% reduction for ovarian cancer risk (RR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.76–0.85; P<0.001) and a reduction of similar magnitude for peritoneal cancers (RR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.66–0.98; P=0.03) (ICD-10 code C48, which includes both peritoneal and retroperitoneal cancers). We found a large reduction in risk of cancers of the fallopian tube, but confidence intervals were wide (RR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.37–0.96, P=0.04).

Relative risk of cancer incidence by site or type among women with vs without tubal ligation. Results are adjusted for age, region, socioeconomic status, parity, age at first birth, hysterectomy, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, body mass index, and use of the oral contraceptive pill or menopausal hormones. The analysis of fallopian tube cancer is restricted to women without bilateral oophorectomy or hysterectomy. The analysis of ovarian cancer is restricted to women without bilateral oophorectomy. Analyses of endometrial and cervical cancer are restricted to women without hysterectomy.

We also found increased risk of anal cancer (RR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.11–1.63; P=0.002), as previously reported (Coffey et al, 2015).

The small increase in risk of lung cancer (RR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.05–1.13) may well be due to residual confounding from smoking — as women with tubal ligation were much more likely to be current smokers, and to smoke more cigarettes per day, than women without tubal ligation. There was no association between tubal ligation and lung cancer risk among never-smokers (RR=1.04; 95% CI: 0.91–1.19).

There were no significant associations between tubal ligation and risk of cancers at the other sites, including cancers of the endometrium, cervix, breast and colorectum.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive analysis so far of the association between tubal ligation and subsequent risk of cancer. We found that tubal ligation was significantly associated with reduced risks of ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube cancers, and an increased risk of anal cancer, but was not associated with breast, endometrial or cervical cancer, as had been suggested by others.

The reduction in ovarian cancer risk has been reported by others (Cibula et al, 2011; Rice et al, 2012; Sieh et al, 2013). We previously reported significant heterogeneity by histological type of ovarian cancer, finding that tubal ligation was associated with a modest reduction of serous tumours overall (RR=0.84, 95% CI: 0.77–0.92), and about a 20% reduction in risk of high-grade serous carcinoma, and almost a halving of risk of endometrioid and clear cell ovarian tumours (Gaitskell et al, 2016). These findings are consistent with hypotheses regarding possible different origins of the ovarian cancer histotypes, and that many cases of high-grade serous ovarian cancer may arise from precursor lesions within the fallopian tubes, while some endometrioid and clear cell tumours may develop from endometriosis (Kurman and Shih, 2011; Prat, 2012). Although the precise mechanism by which tubal ligation reduces the risk of ovarian cancer is unclear, part of the explanation could be that it acts as a physical barrier to pro-cancerous substances passing through the fallopian tubes to the ovaries (whether endometriosis, fallopian tube epithelial cells, infectious agents, or exogenous carcinogens).

Few other studies have reported on the association between tubal ligation and risk of peritoneal cancer, and they have tended to be limited by small numbers of cases. Our study included 730 cases of peritoneal cancer; two retrospective studies have reported their findings—one study including 62 cases found no association (Grant et al, 2010); and another including 22 cases reported a reduced risk (Purdie et al, 1995; Green et al, 1997).

We believe that this is the first study to report that tubal ligation is associated with a significant reduction in risk of fallopian tube cancer (Riska et al, 2007; Vicus et al, 2010).

Our finding that tubal ligation is associated with a reduction in risk of ovarian, peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers perhaps reflects their histological and clinical similarity, and possible similar site of origin (Kurman et al, 2014). The majority of the peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers with specified histology were serous carcinomas, which is also the most common histotype of ovarian cancer (Gaitskell et al, 2016). There is increasing evidence from histological, molecular and genetics studies that many high-grade serous carcinomas found in the ovary or peritoneum may have originated from precursor lesions in the fallopian tube (reviewed in (Nik et al, 2014; Perets and Drapkin, 2016)).

As the majority of the putative precursor lesions for high-grade serous cancers are found within the fimbrial end of the fallopian tube (Przybycin et al, 2010; Gilks et al, 2015), adjacent to the ovary, it is perhaps surprising that tubal ligation (which normally involves surgery to the mid-portion of the tube) should reduce the risk of such tumours. It may be that, historically, some surgical sterilisation procedures involved cutting and removing a portion of the fallopian tube, rather than simply clipping the tube (as is now more common). Alternatively, it may be that surgery causes local vascular changes with consequent effects on the tubal epithelium. One of the limitations of our study is that we do not have information on the type of surgical procedure performed, and thus are unable to explore possible differences in association between different surgical techniques.

For endometrial cancer, a reduced risk associated with tubal ligation was reported in a Danish cohort (Kjaer et al, 2004), but we and others have not replicated this association (Castellsague et al, 1996; Lacey et al, 2000). One group of investigators reported that tubal ligation was associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer (Mathews et al, 2012), but again, neither other findings (Li and Thomas, 2000) nor ours replicated this.

Reports of the relationship between tubal ligation and breast cancer risk have been varied, including suggestions of either a reduced (Kreiger et al, 1999; Calle et al, 2001) or increased risk (Irwin et al, 1988), although the majority of studies reported no significant association (Brinton et al, 2000; Eliassen et al, 2006; Iversen et al, 2007; Dorjgochoo et al, 2009; Press et al, 2011; Gaudet et al, 2013; Nichols et al, 2013), consistent with our findings.

We have previously reported in detail on the risk factors for anal cancer in the Million Women Study (Coffey et al, 2015); factors associated with an increased risk of anal cancer included tubal ligation, nulliparity, smoking, past use of the oral contraceptive pill, and not living with a partner. The strongest association was with a history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (RR=4.03, 95% CI: 2.59–6.28), reflecting the importance of high-risk strains of human papilloma virus as causative agents of both cervical (Walboomers et al, 1999) and anal (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2009) cancers. It is unclear why tubal ligation should be associated with an increased risk of anal cancer, and it may be that this apparent association reflects confounding by sexual behaviour and exposure to human papilloma virus. For example, as tubal ligation is usually performed for permanent contraception, it is likely to be more common among women who are sexually active, and who thus may be more likely to be exposed to sexually-transmitted infections, such as human papilloma virus, and the consequent increased risk of anal cancer.

There have been reports on possible relationships between tubal ligation and other cancers, including possible reductions in risk of colorectal (Cape and Kreiger, 1999; Rosenblatt et al, 2004) and stomach cancer (Dorjgochoo et al, 2009), and increased risks of thyroid cancer (Braganza et al, 2014) and lymphatic and haematopoietic malignancies (Kjaer et al, 2004). We did not replicate any of these findings.

The large size of the cohort, the individual information on possible confounding factors, and the complete and long follow-up, provided reliable estimates of risks associated with tubal ligation for 26 specific cancer sites, even relatively uncommon ones. We found no association between tubal ligation and the risk of cancers of the endometrium, breast, or cervix. By contrast, tubal ligation is associated with a clear reduction in risk of ovarian cancer, a reduction of similar magnitude of peritoneal cancer, and a reduction of fallopian tube cancer. That tubal ligation is associated with a reduced risk of cancers of the ovary, peritoneum and fallopian tube, but not of other hormonally-related cancers, is consistent with the hypothesis that many of the cancers at these sites have a shared origin in the fallopian tube, and that tubal ligation reduces cancer risk by acting as a barrier to cells, carcinogens or other agents reaching the ovary and peritoneal cavity, rather than by affecting hormone levels.

Change history

26 April 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arnold M (2015) Jasper: Jasper makes plots. R package version 2-192.

Braganza MZ, de Gonzalez AB, Schonfeld SJ, Wentzensen N, Brenner AV, Kitahara CM (2014) Benign breast and gynecologic conditions, reproductive and hormonal factors, and risk of thyroid cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 7 (4): 418–425.

Brinton LA, Gammon MD, Coates RJ, Hoover RN (2000) Tubal ligation and risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 82 (9): 1600–1604.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker KA, Wingo PA, Petrelli JM, Thun MJ (2001) Tubal sterilization and risk of breast cancer mortality in US women. Cancer Causes Control 12 (2): 127–135.

Cape DB, Kreiger N (1999) Gynaecological surgical procedures and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Eur J Cancer Prev 8 (6): 495–500.

Castellsague X, Thompson WD, Dubrow R (1996) Tubal sterilization and the risk of endometrial cancer. Int J Cancer 65 (5): 607–612.

Cibula D, Widschwendter M, Majek O, Dusek L (2011) Tubal ligation and the risk of ovarian cancer: review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 17 (1): 55–67.

Coffey K, Beral V, Green J, Reeves G, Barnes I (2015) Lifestyle and reproductive risk factors associated with anal cancer in women aged over 50 years. Br J Cancer 112 (9): 1568–1574.

Dorjgochoo T, Shu XO, Li HL, Qian HZ, Yang G, Cai H, Gao YT, Zheng W (2009) Use of oral contraceptives, intrauterine devices and tubal sterilization and cancer risk in a large prospective study, from 1996 to 2006. Int J Cancer 124 (10): 2442–2449.

Eliassen AH, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Hankinson SE (2006) Tubal sterilization in relation to breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer 118 (8): 2026–2030.

Gaitskell K, Green J, Pirie K, Reeves G, Beral V on behalf of the Million Women Study Collaborators (2016) Tubal ligation and ovarian cancer risk in a large cohort: Substantial variation by histological type. Int J Cancer 138 (5): 1076–1084.

Gaudet MM, Patel AV, Sun J, Teras LR, Gapstur SM (2013) Tubal sterilization and breast cancer incidence: results from the cancer prevention study II nutrition cohort and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 177 (6): 492–499.

Gilks CB, Irving J, Kobel M, Lee C, Singh N, Wilkinson N, McCluggage WG (2015) Incidental nonuterine high-grade serous carcinomas arise in the fallopian tube in most cases: further evidence for the tubal origin of high-grade serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 39 (3): 357–364.

Grant DJ, Moorman PG, Akushevich L, Palmieri RT, Bentley RC, Schildkraut JM (2010) Primary peritoneal and ovarian cancers: an epidemiological comparative analysis. Cancer Causes Control 21 (7): 991–998.

Green A, Purdie D, Bain C, Siskind V, Russell P, Quinn M, Ward B (1997) Tubal sterilisation, hysterectomy and decreased risk of ovarian cancer. Survey of Women's Health Study Group. Int J Cancer 71 (6): 948–551.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2009) A review of human carcinogens. Part B: Biological agents: Human Papillomaviruses Vol. 100B. IARC Press: Lyon, France.

Irwin KL, Lee NC, Peterson HB, Rubin GL, Wingo PA, Mandel MG (1988) Hysterectomy, tubal sterilization, and the risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 127 (6): 1192–1201.

Iversen L, Hannaford PC, Elliott AM (2007) Tubal sterilization, all-cause death, and cancer among women in the United Kingdom: evidence from the Royal College of General Practitioners' Oral Contraception Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196 (5): 447 e1–447 e8.

Kjaer SK, Mellemkjaer L, Brinton LA, Johansen C, Gridley G, Olsen JH (2004) Tubal sterilization and risk of ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer. A Danish population-based follow-up study of more than 65 000 sterilized women. Int J Epidemiol 33 (3): 596–602.

Kreiger N, Sloan M, Cotterchio M, Kirsh V (1999) The risk of breast cancer following reproductive surgery. Eur J Cancer 35 (1): 97–101.

Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH (Eds) (2014) WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. 4th edn. IARC: Lyon.

Kurman RJ, Shih IeM (2011) Molecular pathogenesis and extraovarian origin of epithelial ovarian cancer—shifting the paradigm. Hum Pathol 42 (7): 918–931.

Lacey JV Jr, Brinton LA, Mortel R, Berman ML, Wilbanks GD, Twiggs LB, Barrett RJ (2000) Tubal sterilization and risk of cancer of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 79 (3): 482–484.

Li H, Thomas DB (2000) Tubal ligation and risk of cervical cancer. The World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Contraception 61 (5): 323–328.

Mathews CA, Stoner JA, Wentzensen N, Moxley KM, Tenney ME, Tuller ER, Myers T, Landrum LM, Lanneau G, Zuna RE, Gold MA, Wang SS, Walker JL (2012) Tubal ligation frequency in Oklahoma women with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 127 (2): 278–282.

Million Women Study Collaborators (2003) Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet 362 (9382): 419–427.

Nichols HB, Baird DD, DeRoo LA, Kissling GE, Sandler DP (2013) Tubal ligation in relation to menopausal symptoms and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer 109 (5): 1291–1295.

Nik NN, Vang R, Shih IeM, Kurman RJ (2014) Origin and pathogenesis of pelvic (ovarian, tubal, and primary peritoneal) serous carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol 9: 27–45.

Perets R, Drapkin R (2016) It's totally tubular...riding the new wave of ovarian cancer research. Cancer Res 76 (1): 10–17.

Prat J (2012) Ovarian carcinomas: five distinct diseases with different origins, genetic alterations, and clinicopathological features. Virchows Arch 460 (3): 237–249.

Press DJ, Sullivan-Halley J, Ursin G, Deapen D, McDonald JA, Strom BL, Norman SA, Simon MS, Marchbanks PA, Folger SG, Liff JM, Burkman RT, Malone KE, Weiss LK, Spirtas R, Bernstein L (2011) Breast cancer risk and ovariectomy, hysterectomy, and tubal sterilization in the women's contraceptive and reproductive experiences study. Am J Epidemiol 173 (1): 38–47.

Przybycin CG, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, Shih Ie M, Vang R (2010) Are all pelvic (nonuterine) serous carcinomas of tubal origin? Am J Surg Pathol 34 (10): 1407–1416.

Purdie D, Green A, Bain C, Siskind V, Ward B, Hacker N, Quinn M, Wright G, Russell P, Wright G, Susil B (1995) Reproductive and other factors and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: an Australian case-control study. Survey of Women's Health Study Group. Int J Cancer 62 (6): 678–684.

R Development Core Team (2015) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria.

Rice MS, Murphy MA, Tworoger SS (2012) Tubal ligation, hysterectomy and ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. J Ovarian Res 5 (1): 13.

Riska A, Sund R, Pukkala E, Gissler M, Leminen A (2007) Parity, tubal sterilization, hysterectomy and risk of primary fallopian tube carcinoma in Finland, 1975–2004. Int J Cancer 120 (6): 1351–1354.

Rosenblatt KA, Gao DL, Ray RM, Nelson ZC, Thomas DB (2004) Contraceptive methods and induced abortions and their association with the risk of colon cancer in Shanghai, China. Eur J Cancer 40 (4): 590–593.

Sieh W, Salvador S, McGuire V, Weber RP, Terry KL, Rossing MA, Risch H, Wu AH, Webb PM, Moysich K, Doherty JA, Felberg A, Miller D, Jordan SJ, Goodman MT, Lurie G, Chang-Claude J, Rudolph A, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Hogdall E, Bandera EV, Olson SH, King MG, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Kiemeney LA, Marees T, Massuger LF, van Altena AM, Ness RB, Cramer DW, Pike MC, Pearce CL, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM, Whittemore AS (2013) Tubal ligation and risk of ovarian cancer subtypes: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Int J Epidemiol 42 (2): 579–589.

StataCorp (2015) Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. StataCorp LP: College Station, TX.

The Million Women Study Collaborative Group (1999) The Million Women Study: design and characteristics of the study population. Breast Cancer Res 1 (1): 73–80.

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A (1988) Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. Croom Helm: London.

Vicus D, Finch A, Rosen B, Fan I, Bradley L, Cass I, Sun P, Karlan B, McLaughlin J, Narod SA Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group (2010) Risk factors for carcinoma of the fallopian tube in women with and without a germline BRCA mutation. Gynecol Oncol 118 (2): 155–159.

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N (1999) Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 189 (1): 12–19.

World Health Organization (1992) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision edn. World Health Organization: Geneva.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the women who participated in the Million Women Study, and the staff from the NHS Breast Screening Centres. Authors gratefully acknowledge the past and present members of Professor Ahmed’s research group (especially Dr Yiyan Zheng, Dr Karin Hellner, Dr Sandra Herrero Gonzalez, David Mannion, Dr Fabrizio Miranda, Mr Pubudu Pathiraja, and Charlotte Taylor), whose questions and discussions initially provoked these analyses. Authors also thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions—particularly Dr Steven Narod for proposing that we conduct analyses on fallopian tube cancer. The Million Women Study is funded by Cancer Research UK (Grant No. C570/A16491) and the UK Medical Research Council (Grant No. MR/K02700X/1). This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Grant Number C38302/A17318, through a CRUK Oxford Centre Clinical Research Training Fellowship for KG.

Million Women Study Co-ordinating Centre StaffHayley Abbiss, Simon Abbott, Rupert Alison, Naomi Allen, Miranda Armstrong, Krys Baker, Angela Balkwill, Emily Banks, Isobel Barnes, Valerie Beral, Judith Black, Roger Blanks, Kathryn Bradbury, Anna Brown, Benjamin Cairns, Karen Canfell, Dexter Canoy, Andrew Chadwick, Barbara Crossley, Francesca Crowe, Dave Ewart, Sarah Ewart, Lee Fletcher, Sarah Floud, Toral Gathani, Laura Gerrard, Adrian Goodill, Jane Green, Lynden Guiver, Michal Hozak, Isobel Lingard, Sau Wan Kan, Oksana Kirichek, Nicky Langston, Bette Liu, Kath Moser, Kirstin Pirie, Gillian Reeves, Keith Shaw, Emma Sherman, Helena Strange, Sian Sweetland, Sarah Tipper, Ruth Travis, Lyndsey Trickett, Lucy Wright, Owen Yang, Heather Young.

Million Women Study Advisory CommitteeEmily Banks, Valerie Beral, Lucy Carpenter, Carol Dezateux, Jane Green, Julietta Patnick, Richard Peto, Cathie Sudlow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Members of the Million Women Study collaborators are listed before the references.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gaitskell, K., Coffey, K., Green, J. et al. Tubal ligation and incidence of 26 site-specific cancers in the Million Women Study. Br J Cancer 114, 1033–1037 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.80

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.80

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chancen und Limitationen der nichthormonellen Kontrazeption

Die Gynäkologie (2024)

-

A systematic review and meta-analysis on tubal ligation and breast cancer risk

Systematic Reviews (2022)

-

Comparing options for females seeking permanent contraception in high resource countries: a systematic review

Reproductive Health (2021)

-

Tubal ligation and endometrial Cancer risk: a global systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Cancer (2019)

-

Survey of pelvic reconstructive surgeons on performance of opportunistic salpingectomy at the time of pelvic organ prolapse repair

International Urogynecology Journal (2019)