Abstract

Background:

Combined oral contraceptive (COC) use reduces epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) risk. However, little is known about risk with COC use before the first full-term pregnancy (FFTP).

Methods:

This Canadian population-based case–control study (2001–2012) included 854 invasive cases/2139 controls aged ⩾40 years who were parous and had information on COC use. We estimated odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for study site, age, parity, breastfeeding, age at FFTP, familial breast/ovarian cancer, tubal ligation, and body mass.

Results:

Among parous women, per year of COC use exclusively before the FFTP was associated with a 9% risk reduction (95% CI=0.86–0.96). Results were similar for high-grade serous and endometrioid/clear cell EOC. In contrast, per year of use exclusively after the FFTP was not associated with risk (aOR=0.98, 95% CI=0.95–1.02).

Conclusions:

Combined oral contraceptive use before the FFTP may provide a risk reduction that remains for many years, informing possible prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Combined oral contraceptive (COC) use is an established factor that consistently reduces the risk for epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC; Beral et al, 2008). Less is known about the association between EOC risk and COC use with respect to the timing of full-term births. Increasing parity reduces EOC risk (Hankinson and Danforth, 2006), but it is difficult to tease apart the independent effects of COC use and parity. The total number of ovulatory years between menarche and menopause has been used, but this does not address the timing of COC use with respect to full-term births. Studies of breast cancer (Schlesselman, 1989; Romieu et al, 1990; Kahlenborn et al, 2006) and endometrial cancer (Cook et al, 2014) have reported a long-term effect with the use of COCs before the first full-term pregnancy (FFTP) among parous women. We therefore investigated the EOC risk associated with COC use, focusing on COC use before the FFTP.

Materials and methods

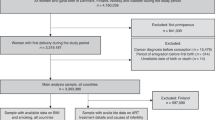

This Canadian population-based case–control study has been previously described (Cook et al, 2016) including ethics approvals (Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, Calgary, Alberta (AB) and Research Ethics Board, British Columbia (BC) Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC) and written informed consent. Briefly, cases were identified from the population-based BC and AB cancer registries who were: age 20–79 years (40–79 in AB); diagnosed with first primary, incident, histologically confirmed EOC (invasive EOC in AB); and able to complete study in English. A total of 1505 cases (60% of 2522 eligible) completed the study. Eligible controls identified from provincial health rosters and a mammography screening program (Eheman et al, 2014) were: aged 20–79 years (40–79 in AB); able to complete study in English; and, had at least one ovary. A total of 2564 (53% of 4838 eligible) completed the study.

Risk factor information was ascertained through the diagnosis date (month/year) for cases and an assigned reference date (month/year) for controls based on an age-frequency match with cases. Respondents completed a self-administered questionnaire (BC before 2005) or a telephone interview (AB and BC after 2005). In additional to demographic, lifestyle, and medical/reproductive factors, women provided information on COC use, including dates or ages of use. Specific COC names were not ascertained. Histotypes were determined by re-review of haematoxylin and eosin slides according to contemporary criteria (Köbel et al, 2014) for 979 women (85.6%).

The analysis was restricted to those ⩾40 years of age at diagnosis/reference date (1144 invasive cases and 2513 controls). Combined oral contraceptive use was evaluated as: non-use (never or <0.5 years) vs ever use (⩾0.5 years); continuous duration (years, ever users only) and, as categorical duration (non-use, <5 years, 5–10, ⩾10 years, and unknown). We used logistic regression to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in R software (R Development Team, 2015). All variables in Table 1 were evaluated as potential confounders. Final aORs included matching variables (Alberta, BC before 2005, BC after 2005, and 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ⩾70 years of age), parity (0, 1, 2, ⩾3 or 1, 2, ⩾3 when restricted to parous women), age at FTTP (⩽24, 25–29, ⩾30 years), breastfeeding (never, ever), first degree family female breast or ovarian cancer (no, yes), tubal ligation (no, yes), and BMI (<25, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, ⩾35 kg m−2). Other variables did not alter the estimated ORs by more than 10%. Histotype-specific analyses were restricted to high-grade serous and combined endometrioid/clear cell, due to few cases of other histotypes. Because COC use exclusively before and exclusively after the FFTP were mutually exlcusive, they were modelled simultaneously, allowing direct comparisons of the two risk estimates using contrasts (Montgomery, 2012).

Results

Characteristics of parous cases and controls are described in Table 1. Combined oral contraceptive use was common among parous women, reported by 61% of cases and 80% of controls. With respect to the timing of COC use (Table 2), use of COCs before and after the FFTP (aOR=0.45, 95% CI=0.34–0.59; per year of use: aOR=0.94, 95% CI=0.91–0.98) as well as exclusive use before the FFTP (aOR=0.56, 95% CI=0.42–0.75; per year of use: aOR=0.91, 95% CI=0.86–0.96) was associated with a reduced risk for EOC. Similarly, both before and after the FFTP as well as use exclusively before the FFTP was associated with a reduced risk for both high-grade serous (aOR=0.50, 95% CI=0.35–0.72 and aOR=0.49, 95% CI=0.35–0.70, respectively) and endometrioid/clear cell (aOR=0.52, 95% CI=0.29–0.92 and aOR=0.47, 95% CI=0.27–0.83, respectively) EOC. In contrast, COC use exclusively after the first birth was associated with a smaller reduction in EOC risk (aOR=0.78, 95% CI=0.61–1.01) that was suggestive but there was no association with increasing duration (per year of use aOR=0.98, 95% CI=0.95–1.02). When the risk estimate for exclusive use before the FFTP was compared (via contrasts) with the risk estimate for exclusive use after, the aORs were found to be significantly different (P-value, <0.01) (Table 2).

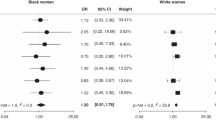

When we stratified by age at FFTP, COC use before and after as well as exclusively before the FFTP was consistently associated with a reduction in EOC risk regardless of age at first birth, a consistency that was not seen with COC use exclusively after the FFTP (Figure 1), although some results were unstable. Similar results were noted when stratified by parity, although risk estimates were more similar for parity ⩾3 (Figure 1).

Combined oral contraceptive use with respect to the FFTP by age at first birth ( A ) and by number of births (parity) ( B ) among parous women. The aORs are adjusted for the following: study site (Alberta, BC before 2005, BC after 2005); age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ⩾70 years); parity in Panel A only (1, 2, ⩾3); age at FFTP in Panel B only (⩽24, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, ⩾35 years); breastfeeding (never, ever); first degree female family history of breast or ovarian cancer (no, yes); tubal ligation (no, yes); BMI (<25, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, ⩾35 kg m−2).

The association of COC use and EOC risk for our entire study population (both parous and non-parous women combined) was consistent with the reported literature (Supplementary Tables 1–4). Any COC use was associated with a reduction in risk (aOR=0.58, 95% CI=0.49, 0.69). Among COC users, risk was most strongly reduced with longer durations of use overall, within more recent time since last use, and for younger ages at first use.

Conclusion

When we assessed the timing of COC use exclusively before the FFTP among parous women, we found a strong reduction in risk (∼40%), which was almost as strong as the ∼50% risk reduction seen with COC before and after the FFTP. Even for fairly short-term COC use (<5 years) before the FFTP there was a significant and substantial reduction in risk years later in parous women. This result is surprising, given that these women all experienced the reduction in risk associated with being parous, and given that the literature (Beral et al, 2008) and our own results for parous and non-parous women indicating that last use of COCs in the more distant past is associated with weaker reductions in risk. In contrast, the effect of such use after the FTTP was of lesser magnitude, despite the assumption that the cessation of ovulation in these women should have equivalent effects regardless of the timing of COCs.

Consistent with our findings, other studies have reported that any use of COCs before age 20 years (Ness et al, 2000; Kumle et al, 2004; Beral et al, 2008; Lurie et al, 2008) or 25 years (Bosetti et al, 2002) is associated with a reduced EOC risk of 29–50% many years later. Ours is the first study to assess COC use exclusively before and after the FFTP to evaluate the timing of COC use with pregnancy.

Although the more immediate effects of COC use on biological end points such as hormone levels, gene expression, and ovulation are well documented, the long-term effects on EOC risk are largely attributed to fewer ovulations during reproductive life (Fathalla, 1971), with the assumption that the timing of ovulation reduction does not matter. Our results could be due, in part, to fewer ovulations because of COC use, but it is not clear why use before the FFTP would have such a strong, lasting impact on EOC risk. In breast cancer, the elevated risk noted with COC use before the FFTP has been hypothesised to be related to the carcinogenic susceptibility of undifferentiated breast tissue at this time (Romieu et al, 1990), and in endometrial cancer the reduction in risk with early COC use is unknown but may be related to a lasting effect on hormone levels that reduce cellular proliferation (Chan et al, 2007). Whether such mechanisms are also applicable to a long-lasting reduction in EOC risk is not clear. Regardless of the tissue of origin for EOC (fallopian tube, endometrium, ovary, etc.), our results suggest that the timing of ovulation reduction is important, and that there may be other long-term mechanisms for an EOC risk reduction beyond ovulation that manifest before the FFTP.

Study strengths include the population-based design; large sample size; restriction to first primary, histologically confirmed invasive EOC; detailed information on parity; assessment of contemporary histotypes (Köbel et al, 2014); high prevalence of COC use; and, restriction to parous women with adjustment for parity, thus minimising confounding by parity. Limitations include: no COC name/dosage information; cases recalling past COC use more fully than controls (but that would bias risk estimates to the null value); relatively low response percentage among the control women; and, possible residual confounding. In addition, COC use in this study represents formulations of COC available in the past, and current formulations may not have the same long-term effects.

In summary, the significant reduction in EOC risk observed with COC use before the FFTP among parous women is a novel and requires replication. Despite the consistently reported risk reduction in EOC with COCs, questions remain about the timing of use and the underlying biological mechanisms of long-term effects to guide future EOC risk prediction (Pearce et al, 2015) and directed chemoprevention strategies for high-risk women (Walker et al, 2015).

Change history

17 January 2017

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G (2008) Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23 257 women with ovarian cancer and 87 303 controls. Lancet 371: 303–314.

Bosetti C, Negri E, Trichopoulos D, Franceschi S, Beral V, Tzonou A, Parazzini F, Greggi S, La Vecchia C (2002) Long-term effects of oral contraceptives on ovarian cancer risk. Int J Cancer 102: 262–265.

Chan M-F, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Khaw KT (2007) Past oral contraceptive and hormone therapy use and endogenous hormone concentrations in postmenopausal women. Menopause 15: 332–339.

Cook LS, Dong Y, Round P, Huang X, Magliocco AM, Friedenreich CM (2014) Hormone contraception before the first birth and endometrial cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23: 356–361.

Cook LS, Leung ACY, Swenerton K, Gallagher RP, Magliocco A, Steed H, Koebel M, Nation J, Eshragh S, Brooks-Wilson A, Le ND (2016) Adult lifetime alcohol consumption and invasive epithelial ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case-control study. Gynecol Oncol 140: 277–284.

Eheman CR, Leadbetter S, Benard VB, Blyth Ryerson A, Royalty JE, Blackman D, Pollack LA, Adams PW, Babcock F (2014) National breast and cervical cancer early detection program data validation project. Cancer 120 (Suppl 16): 2597–2603.

Fathalla MF (1971) Incessant ovulation—a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet 2: 163.

Hankinson SE, Danforth KN (2006) Ovarian Cancer. Oxford University Press: Oxford; New York.

Kahlenborn C, Modugno F, Potter DM, Severs WB (2006) Oral contraceptive use as a risk factor for premenopausal breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 81: 1290–1302.

Köbel M, Bak J, Bertelsen BI, Carpen O, Grove A, Hansen ES, Jakobsen AML, Lidang M, Masback A, Tolf A, Gilks CB, Carlson JW (2014) Ovarian carcinoma histotype determination is highly reproducible, and is improved through the use of immunohistochemistry. Histopathology 64: 1004–1013.

Kumle M, Weiderpass E, Braaten T, Adami HO, Lund E, Norwegian-Swedish Women's L, Health Cohort S (2004) Risk for invasive and borderline epithelial ovarian neoplasias following use of hormonal contraceptives: the Norwegian-Swedish Women's Lifestyle and Health Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 90: 1386–1391.

Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Thompson PJ, Mcduffie KE, Carney ME, Terada KY, Goodman MT (2008) Combined oral contraceptive use and epithelial ovarian cancer risk: time-related effects. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 19: 237–243.

Montgomery D (2012) Design and Analysis of Experiments. Wiley E-Text.

Ness RB, Grisso JA, Klapper J, Schlesselman JJ, Silberzweig S, Vergona R, Morgan M, Wheeler JE (2000) Risk of ovarian cancer in relation to Oestrogen and progestin dose and use characteristics of oral contraceptives. SHARE Study Group. Steroid Hormones and Reproductions. Am J Epidemiol 152: 233–241.

Pearce CL, Stram DO, Ness RB, Stram DA, Roman LD, Templeman C, Lee AW, Menon U, Fasching PA, Mcalpine JN, Doherty JA, Modugno F, Schildkraut JM, Rossing MA, Huntsman DG, Wu AH, Berchuck A, Pike MC, Pharoah PD (2015) Population distribution of lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24: 671–676.

R Development Core Team (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.

Romieu I, Berlin JA, Colditz G (1990) Oral contraceptives and breast cancer. Review and meta-analysis. Cancer 66: 2253–2263.

Schlesselman JJ (1989) Cancer of the breast and reproductive tract in relation to use of oral contraceptives. Contraception 40: 1–38.

Walker JL, Powell CB, Chen LM, Carter J, Bae Jump VL, Parker LP, Borowsky ME, Gibb RK (2015) Society of gynecologic oncology recommendations for the prevention of ovarian cancer. Cancer 121: 2108–2120.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by two grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and by a grant from WorkSafe BC (formerly, the Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia). LSC receives support from the UNM Comprehensive Cancer Center, a recipient of NCI Cancer Support Grant 2 P30 CA118100-11. This research was presented as an oral presentation at the March 2016 ASPO meeting in Columbus, Ohio and published in abstract form. (LSC, CR Pestak, ACY Leung, Le N (2016) Hormone contraception before the first birth and ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 25: 561).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, L., Pestak, C., Leung, A. et al. Combined oral contraceptive use before the first birth and epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Br J Cancer 116, 265–269 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.400

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.400