Abstract

Background:

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) is associated with a reduced risk of several cancers. However, studies conducted in Mediterranean regions are scanty.

Methods:

To investigate the relation between MD and colorectal cancer risk in Italy, we pooled data from three case–control studies, including a total of 3745 colorectal cancer cases and 6804 hospital controls. Adherence to the MD was assessed using an a priori Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), based on nine components.

Results:

Compared with the lowest adherence to the MD (0–2 MDS), the odds ratio (OR) was 0.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43–0.62) for the highest adherence (7–9 MDS), with a significant inverse trend in risk (P<0.0001). The OR for a 1-point increment in the MDS was 0.89 (95% CI 0.86–0.91). The inverse association was consistent across studies, cancer anatomical subsites and strata of selected covariates.

Conclusions:

This Italian study confirms a favourable role of MD on colorectal cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The role of single foods and nutrients in colorectal carcinogenesis is well documented (World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research, 2012). However, as dietary components are interrelated and may act synergistically, it may be more informative to investigate the relation of colorectal cancer with dietary patterns.

The Mediterranean diet (MD) is characterised by a frequent consumption of vegetables, legumes, fruit and nuts, cereals, fish, and olive oil as the main seasoning fat; a modest intake of wine, generally during meals; a low-to-moderate consumption of dairy products; and a low consumption of meat (Trichopoulou et al, 2000). In terms of nutrients, MD is rich in fibres, antioxidants, folates, flavonoids, and monounsaturated fats (oleic acid), with anticarcinogenic activity (La Vecchia et al, 1997; Rossi et al, 2010; Praud et al, 2014; Rotelli et al, 2015).

A high adherence to the MD has been associated with a reduced risk of several cancers, including those of the digestive system (Bosetti et al, 2013; Filomeno et al, 2014; Praud et al, 2014; Schwingshackl and Hoffmann, 2014). A meta-analysis of five cohort and two case–control studies reported a statistically significant 14% reduction of colorectal cancer risk, similar for cohort and case–control studies (Schwingshackl and Hoffmann, 2014). However, only three studies were conducted in countries with typical MD: a Greek (Kontou et al, 2012) and an Italian (Grosso et al, 2014) case–control studies and an Italian cohort study (Agnoli et al, 2013), part of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (Bamia et al, 2013).

Thus we assessed the relation between the MD and colorectal cancer risk in Italy.

Materials and methods

Study population

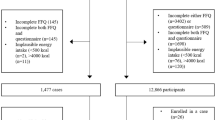

We pooled data from three hospital-based case–control studies on colorectal cancer, including a total of 3745 incident, histologically confirmed colorectal cancer cases and 6804 controls. The oldest study, conducted in 1985–91 in Milan, included 1326 cases (median age 62, range 20–74 years) and 2081 controls (median age 55, range 19–74 years) (La Vecchia et al, 1988); the second study, conducted in 1992–96 in Milan, Genoa, Pordenone, Gorizia, Forlì, Latina, and Naples, included 1953 cases (median age 62, range 19–74 years) and 4154 controls (median age 58, range 19–74 years) (Franceschi et al, 1997); the third study, conducted in 2008–10 in Milan, Pordenone, and Udine, included 466 cases (median age 67, range 35–80 years) and 569 controls (median age 66, range 31–80 years). Overall, 488 cases were cancers of the proximal colon (appendix, caecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon), 1078 of the distal colon (splenic flexure, descending, sigmoid colon), 788 of overlapping or not otherwise specified colon, 1383 of rectum (rectum and rectosigmoid junction), and 8 of not otherwise specified colorectum. Controls were subjects who had not recently changed their diet and had been admitted to the same hospitals as cases for a wide spectrum of acute, non-neoplastic conditions unrelated to known colorectal cancer risk factors (28% traumas, 24% other orthopedic disorders, 23% surgical conditions, 12% eye diseases, 12% other illnesses).

Patients were interviewed in hospital by trained interviewers, using structured questionnaires collecting information on socio-demographic factors, lifestyle habits (including smoking and alcohol drinking), anthropometric measures, physical activity, medical history, and family history of cancer. Information on patients’ usual diet in the 2 years before diagnosis/interview was assessed through food frequency questionnaires, collecting information on weekly consumption of 29 foods in the first study (D'Avanzo et al, 1997), and 78 or 56 foods, respectively, in the other two studies, (Franceschi et al, 1993). Occasional intake (1–3 times per month) was coded as 0.5 per week. The questionnaire of the first study was tested for reproducibility (D'Avanzo et al, 1997), and those of the other two studies for reproducibility (Franceschi et al, 1993; Franceschi et al, 1995; Pearson’s correlation coefficients for most foods 60–80%) and validity (Decarli et al, 1996; subjects correctly classified within one quintile of nutrients were 73%). Intake of nutrients and total energy were computed using Italian food composition databases (Gnagnarella et al, 2004).

The study protocols were approved by the ethical boards, and all participants signed an informed consent. Refusal to participate was <5% for either cases or controls.

Supplementary Table S1 gives the distribution of cases and controls according to main characteristics.

Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS)

Adherence to the traditional MD was assessed through an a priori defined score (Trichopoulou et al, 2003), based on nine dietary components. For components frequently consumed in the MD (vegetables, legumes, fruit/nuts, cereals, fish/seafood, and a high monounsaturated to saturated fat ratio), participants with consumption above or equal to the study- and sex-specific median value among controls were assigned a value of 1 and 0 otherwise. For components less frequently consumed in the MD (dairy and meat/meat products), participants with consumption above or equal to the median value were assigned a value of 0 and 1 otherwise. For alcohol, a value of 1 was assigned to moderate drinkers (drinking below the study- and sex-specific median intake) and a value of 0 to non-drinkers and drinkers with an intake above the median values. Supplementary Table S2 shows the study- and sex-specific median values of each component of the MD among controls. The MDS was calculated for each subject by adding up the points for each of the nine components and ranged between 0 (lowest adherence) and 9 (highest adherence).

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) of colorectal cancer and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated through unconditional logistic regression models, including categorical terms for age, sex, calendar period, centre, education, body mass index, occupational physical activity, family history of intestinal cancer, and study-specific total energy intake. Further adjustment for smoking did not change ORs. The few missing values for adjusting covariates were imputed as median values, but the risk estimates did not change when missing values were considered as indicators or when we restricted the analyses to the individuals with complete data only. Tests for linear trend were based on the likelihood-ratio test between the models with and without a linear term for the score.

Results

High vs low consumption of vegetables (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.63–0.75), legumes (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.64–0.76), fruit and nuts (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.73–0.87), fish (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.71–0.85), monounsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80–0.95), and low vs high consumption of meat (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.79–0.94) were associated with a significantly reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Alcohol intake was not related (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.96–1.18), and high vs low intake of cereals/potatoes (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.24) and low vs high intake of milk/dairy products (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.00–1.19) significantly increased colorectal cancer risk (Table 1).

Compared with a 0–2 MDS (lowest adherence), the OR was 0.52 (95% CI 0.43–0.62) for a 7–9 MDS (highest adherence), with a significant strong inverse trend in risk (Table 2). The OR for a 1-point increment in the MDS was 0.89 (95% CI 0.86–0.91). The corresponding ORs excluding in turn each of the nine components (sensitivity analysis) ranged from 0.87 (95% CI 0.84–0.89) to 0.92 (95% CI 0.89–0.94).

The inverse relation was consistent across strata of age, sex, education, body mass index, physical activity, energy intake, and history of intestinal cancer in first-degree relatives (Supplementary Table S3).

The OR for a 1-point increment in the MSD was 0.90 (95% CI 0.85–0.96) for proximal colon, 0.88 (95% CI 0.84–0.92) for distal colon, 0.85 (95% CI 0.81–0.89) for overlapping and undefined colon, and 0.90 (95% CI 0.86–0.93) for rectal cancer (Table 3).

Discussion

Combining the three Italian studies, the highest adherence to the MD compared with the lowest reduced colorectal cancer risk by about 50%, consistent across the large bowel. We found a stronger inverse association between MD and colorectal cancer than that reported in a Greek case–control study (OR 0.88; Kontou et al, 2012) but similar to that found in an Italian case–control study (OR 0.46; Grosso et al, 2014) and an Italian cohort study (hazard ratio 0.50; Agnoli et al, 2013) and stronger than that found in a meta-analysis (pooled relative risk of 0.86; Schwingshackl and Hoffmann, 2014). However, comparison between studies is difficult because of the differences of dietary habits between various countries, the use of different components and cut points in the MD definition, and the different prevalence of adherence to the MD. The MDS is based on the median consumption among the control group within the study population, and not in absolute terms, and subjects with a higher MDS in this Italian population are likely to have a higher absolute consumption of foods that are typical of the MD.

Limitations of this study include pooling results from studies with different food frequency questionnaire and possible selection and information bias. However, cases and controls were interviewed in the same hospital setting, had similar very high participation rate, and were from comparable catchment area. We excluded from the controls patients admitted for conditions related to known risk factors for colorectal cancer and those with long-term dietary modifications. The strengths of the study include the use of food frequency questionnaires with satisfactory reproducibility (D'Avanzo et al, 1997; Franceschi et al, 1997) and validity (Decarli et al, 1996). Our estimates were adjusted for major confounding variables, and the consistency of the associations across strata of major covariates rules out a major role of residual confounding. Another strength of our study is the large sample size, based on >3700 cases, and the study population with an overall high adherence to MD, allowing for the investigation of high absolute amounts of foods typical of this diet.

Thus this large study conducted in a Mediterranean region confirms a favourable role of MD on colorectal cancer risk.

Change history

27 September 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Agnoli C, Grioni S, Sieri S, Palli D, Masala G, Sacerdote C, Vineis P, Tumino R, Giurdanella MC, Pala V, Berrino F, Mattiello A, Panico S, Krogh V (2013) Italian Mediterranean Index and risk of colorectal cancer in the Italian section of the EPIC cohort. Int J Cancer 132 (6): 1404–1411.

Bamia C, Lagiou P, Buckland G, Grioni S, Agnoli C, Taylor AJ, Dahm CC, Overvad K, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Cottet V, Boutron-Ruault MC, Morois S, Grote V, Teucher B, Boeing H, Buijsse B, Trichopoulos D, Adarakis G, Tumino R, Naccarati A, Panico S, Palli D, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Duijnhoven FJ, Peeters PH, Engeset D, Skeie G, Lund E, Sanchez MJ, Barricarte A, Huerta JM, Quiros JR, Dorronsoro M, Ljuslinder I, Palmqvist R, Drake I, Key TJ, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Romieu I, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Romaguera D, Norat T, Trichopoulou A (2013) Mediterranean diet and colorectal cancer risk: results from a European cohort. Eur J Epidemiol 28 (4): 317–328.

Bosetti C, Turati F, Dal Pont A, Ferraroni M, Polesel J, Negri E, Serraino D, Talamini R, La Vecchia C, Zeegers MP (2013) The role of Mediterranean diet on the risk of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 109 (5): 1360–1366.

D'Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Katsouyanni K, Negri E, Trichopoulos D (1997) An assessment, and reproducibility of food frequency data provided by hospital controls. Eur J Cancer Prev 6 (3): 288–293.

Decarli A, Franceschi S, Ferraroni M, Gnagnarella P, Parpinel MT, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Salvini S, Falcini F, Giacosa A (1996) Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire to assess dietary intakes in cancer studies in Italy. Results for specific nutrients. Ann Epidemiol 6 (2): 110–118.

Filomeno M, Bosetti C, Garavello W, Levi F, Galeone C, Negri E, La Vecchia C (2014) The role of a Mediterranean diet on the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Br J Cancer 111 (5): 981–986.

Franceschi S, Barbone F, Negri E, Decarli A, Ferraroni M, Filiberti R, Giacosa A, Gnagnarella P, Nanni O, Salvini S, La Vecchia C (1995) Reproducibility of an Italian food frequency questionnaire for cancer studies. Results for specific nutrients. Ann Epidemiol 5 (1): 69–75.

Franceschi S, Favero A, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Conti E, Montella M, Giacosa A, Nanni O, Decarli A (1997) Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer in Italy. Int J Cancer 72 (1): 56–61.

Franceschi S, Negri E, Salvini S, Decarli A, Ferraroni M, Filiberti R, Giacosa A, Talamini R, Nanni O, Panarello G, La Vecchia C (1993) Reproducibility of an Italian food frequency questionnaire for cancer studies: results for specific food items. Eur J Cancer 29A (16): 2298–2305.

Gnagnarella P, Parpinel M, Salvini S, Franceschi S, Palli D, Boyle P (2004) The update of the Italian food composition database. J Food Comp Anal 17: 509–522.

Grosso G, Biondi A, Galvano F, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Buscemi S, Drago F, Basile F (2014) Factors associated with colorectal cancer in the context of the Mediterranean diet: a case-control study. Nutr Cancer 66 (4): 558–565.

Kontou N, Psaltopoulou T, Soupos N, Polychronopoulos E, Xinopoulos D, Linos A, Panagiotakos DB (2012) Metabolic syndrome and colorectal cancer: the protective role of Mediterranean diet—a case-control study. Angiology 63 (5): 390–396.

La Vecchia C, Braga C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Russo A, Conti E, Falcini F, Giacosa A, Montella M, Decarli A (1997) Intake of selected micronutrients and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 73 (4): 525–530.

La Vecchia C, Negri E, Decarli A, D'Avanzo B, Gallotti L, Gentile A, Franceschi S (1988) A case-control study of diet and colo-rectal cancer in northern Italy. Int J Cancer 41 (4): 492–498.

Praud D, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Turati F, Ferraroni M, La Vecchia C (2014) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and gastric cancer risk in Italy. Int J Cancer 134 (12): 2935–2941.

Rossi M, Negri E, Parpinel M, Lagiou P, Bosetti C, Talamini R, Montella M, Giacosa A, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2010) Proanthocyanidins and the risk of colorectal cancer in Italy. Cancer Causes Control 21 (2): 243–250.

Rotelli MT, Bocale D, De Fazio M, Ancona P, Scalera I, Memeo R, Travaglio E, Zbar AP, Altomare DF (2015) In-vitro evidence for the protective properties of the main components of the Mediterranean diet against colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Surg Oncol 24 (3): 145–152.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G (2014) Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer 135 (8): 1884–1897.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D (2003) Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 348 (26): 2599–2608.

Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Kuper H, Trichopoulos D (2000) Cancer and Mediterranean dietary traditions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9 (9): 869–873.

World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research (2012) Colorectal Cancer 2011 Report: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Norman Temple for style editing of the manuscript. This work was funded by the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC) and the Italian Ministry of Health, General Directorate of European and International Relations. VR was supported by a fellowship from the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (FIRC no. 18107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rosato, V., Guercio, V., Bosetti, C. et al. Mediterranean diet and colorectal cancer risk: a pooled analysis of three Italian case–control studies. Br J Cancer 115, 862–865 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.245

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.245

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combined associations of a healthy lifestyle and body mass index with colorectal cancer recurrence and survival: a cohort study

Cancer Causes & Control (2024)

-

Dietary choline and sphingomyelin choline moiety intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a case-control study

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2023)

-

Association between nutrient intake related to the one-carbon metabolism and colorectal cancer risk: a case–control study in the Basque Country

European Journal of Nutrition (2023)

-

A comparative examination of colorectal cancer burden in European Union, 1990–2019: Estimates from Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer

European Journal of Nutrition (2021)