Abstract

Background:

Methylation of repetitive elements Alu and LINE-1 in humans is considered a surrogate for global DNA methylation. Previous studies of blood-measured Alu/LINE-1 and cancer risk are inconsistent.

Methods:

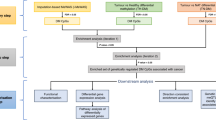

We studied 1259 prospective methylation measurements from blood drawn 1–4 times from 583 participants from 1999 to 2012. We used Cox regression to evaluate time-dependent methylation as a biomarker for cancer risk and mortality, and linear regression to compare mean differences in methylation over time by cancer status and analyse associations between rate of methylation change and cancer.

Results:

Time-dependent LINE-1 methylation was associated with prostate cancer incidence (HR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.01–1.88) and all-cancer mortality (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.03–1.92). The first measurement of Alu methylation (HR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.08–1.79) was associated with all-cancer mortality. Participants who ultimately developed cancer had lower mean LINE-1 methylation than cancer-free participants 10+ years pre-diagnosis (P<0.01). Rate of Alu methylation change was associated with all-cancer incidence (HR: 3.62, 95% CI: 1.09–12.10).

Conclusions:

Our results add longitudinal data on blood Alu and LINE-1 methylation and cancer, and potentially contribute to their use as early-detection biomarkers. Future larger studies are needed and should account for the interval between blood sample collection and cancer diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

DNA methylation aberrations are ubiquitous across various cancers, and are considered a hallmark of cancer (Laird, 2005). In general, cancer is thought to be characterised by global hypomethylation (resulting in increased oncogene expression and genomic instability), and gene-specific promoter hypermethylation (resulting in suppressed DNA repair and other tumour-suppressive functions; Wilson et al, 2007; Ohgane et al, 2008; Hansen et al, 2011). Not only do these methylation changes occur in tumour tissues, but they are frequently mirrored in blood leucocytes (Brennan and Flanagan, 2012; Joyce et al, 2015). Because of the time- and cost-effectiveness and non-invasiveness of blood sample collection, methylation detectable in white blood cells (WBCs) can be collected from healthy individuals for screening before their cancer diagnosis, and has long been a target for researchers attempting to develop new early-detection biomarkers of cancer. As an important, if not essential, part of cancer development, global DNA methylation is one such potential biomarker (Das and Singal, 2004).

Current estimates suggest that over one-third of DNA methylation occurs in repetitive elements (Kochanek et al, 1993; Schmid, 1998). Among these repetitive elements Alu and LINE-1 are the most plentiful families, collectively representing 30% of the human genome (Kazazian and Goodier, 2002; Grover et al, 2004; Babushok and Kazazian, 2007). Because of this high representation, Alu and LINE-1 are often used as surrogates for global DNA methylation (Yang et al, 2004; Weisenberger et al, 2005). Although tissue-specific studies of global DNA methylation have found associations between hypomethylation and increased cancer risk (Cravo et al, 1996; Soares et al, 1999; Bariol et al, 2003; Ehrlich et al, 2006; Van Hoesel et al, 2012), studies involving methylation measured from blood leucocytes have had far more mixed results. Case-control studies found that both hypomethylation (Pufulete et al, 2003; Lim et al, 2008; Moore et al, 2008; Hou et al, 2010; Di et al, 2011) and hypermethylation (Liao et al, 2011; Walters et al, 2013; Neale et al, 2014) were associated with increased cancer risk across multiple tissue types. Prospective studies of global DNA methylation measured at a single time point in blood leucocytes have also found increased cancer risk associated with both global hypomethylation (Gao et al, 2012) and hypermethylation (Andreotti et al, 2014). Furthermore, to our knowledge no prospective study has examined the longitudinal relationship between repeated measures of global DNA methylation and cancer risk over time. There is evidence to suggest a complex biological relationship, with one study suggesting that the timing of blood draws relative to cancer diagnosis matters (Barry et al, 2015), and another finding a ‘U-shaped’ association (Tajuddin et al, 2014).

Faced with these inconsistencies, we set out to use our recently generated multiple measures of Alu and LINE-1 DNA methylation, and perform an update of our previous investigation of global DNA methylation and cancer risk in the Normative Aging Study (NAS; Zhu et al, 2011). The updates to our data set allowed us to increase our sample size, which allows a more thorough analysis of cancer incidence and cancer mortality. Furthermore, the increased follow-up time allows a greater analysis of temporal factors affecting the relationship between global DNA methylation markers and cancer (i.e., the interval between sample collection and cancer diagnosis). Finally, our larger sample allows us to exclude Alu and LINE-1 methylation measures in blood collected after cancer diagnosis, meaning that our new analysis can rule out potential ‘reverse causality’ effects of cancer development on Alu and LINE-1 methylation. Our objective is to leverage additional longitudinal data (and new statistical methods for longitudinal analysis developed by our group) to update our previously published findings regarding Alu and LINE-1 methylation and hazards of cancer incidence and mortality. Our goal is to test the hypothesis that these global DNA methylation surrogates measured in blood leucocytes can be used as biomarkers of cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The NAS was established by the US Department of Veterans Affairs in 1963 with an initial study cohort of 2280 healthy men (aged 21–80 years at enrolment) living in the greater Boston area, of primarily (96%) white race. Since then, participants have been recalled periodically for clinical exams every 3–5 years; starting in 1999 these exams included a 7-ml blood sample for genetic and epigenetic analysis. Between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2012; 802 of 829 active subjects (96.7%) agreed to donate blood for DNA analysis. In total, LINE-1 or Alu methylation was measured at least once in 796 participants. Of these, we excluded 213 participants diagnosed with cancer prior to first blood sample collection, leaving 583 participants cancer-free at the first blood draw for analysis. This population included our previously published study of LINE-1 and Alu methylation and cancer, with an additional 108 cancer cases and 9 new cancer deaths with NAS data collected from 2007 to 2012. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions, and written consent forms were obtained from all participants.

In addition to blood samples, the NAS collected data including anthropometric measurements, standardised medical exams, and questionnaires about medical and smoking history. Our analysis considered the following potential covariates: race (dichotomized as white or non-white), education (<13 years, 13–16 years, >16 years), two cigarette smoking variables (status of never/former/current and pack-years), whether the respondent reported taking two or more alcoholic drinks per day on average, body mass index (BMI) calculated from weight and height measurements, and age. Our multivariable models were also adjusted for WBC count and per cent neutrophils taken from the blood sample, as per previous analyses of blood leucocyte methylation in the NAS (Joyce et al, 2015).

Information on cancer diagnoses was obtained from questionnaires and confirmed via review of medical records and histological reports. In contrast to our previous study (Zhu et al, 2011) of Alu and LINE-1 methylation in the NAS, we excluded participants who had been diagnosed with cancer prior to their first blood draw from all analyses. Among the 583 participants free of cancer at first visit, 138 (23.7%) developed cancer during a median of 10.54 (IQR: 6.02–12.10) years of follow-up, including 46 prostate cancers and 92 other cancers. For participants who died, death certificates were obtained from the appropriate state health department and reviewed to ensure accurate classification of primary cause of death. These included 37 (6.3%) subjects free of cancer at the first blood draw who later died of cancer during median of 11.41 (IQR: 8.43–12.34) years of follow-up, including 5 subjects who died of prostate cancer.

Methylation measurement

The full procedure for blood leucocyte DNA extraction and measurement has been reported previously (Hou et al, 2011). In order to maximise methylation measurement accuracy, we used a pyrosequencing-based assay to measure CpG sites at three positions each for LINE-1 and Alu. All assays used built-in controls. Methylation measurements from each position were averaged via a simple mean, and then standardised by batch number to a mean value of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Figure 1 shows scatter plots of LINE-1 and Alu methylation over time, after batch standardisation. We also show box plots of LINE-1 and Alu methylation over time before (Supplementary Figure 1) and after (Supplementary Figure 2) batch standardisation. Similar to previous reports (Zhu et al, 2011), the within-sample coefficients of variation were 1.6% for Alu and 0.7% for LINE-1.

Statistical analysis

We first examined associations between cancer risk factors at the first visit and global DNA methylation using simple, unadjusted linear regression. Next, we used multiple Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate associations between both first visit and time-dependent global DNA methylation (calculated as the change in methylation between time points for those subjects with multiple measurements), and cancer incidence and mortality. Time-dependent methylation was calculated using all available methylation data, with each subject’s follow-up time divided into intervals by methylation measurement, ensuring that each methylation measurement had its own follow-up period. This included a sensitivity analysis adjusting for batch as a covariate in our models (rather than batch-standardising our methylation measurements) to ensure that this decision in our approach did not meaningfully alter our results. We also examined associations between methylation trajectory and cancer incidence. This was done by comparing the mean difference in methylation between cancer cases and cancer-free individuals each year prior to cancer diagnosis. Owing to low sample size, intervals were collapsed into 5-year increments (<5 years, 5 to <10 years, and >10 years). Logistic regression models corresponding to these categories were run to generate odds ratios stratified by time interval between methylation measurement and cancer diagnosis. We then analysed the relationship between methylation rate of change (in units per year) and cancer incidence and mortality using a linear regression model, to estimate the change in methylation measurement over time for all subjects with multiple measurements, and subsequently treating the β-coefficient from this model as an independent variable in additional Cox regression models. We conducted two additional sensitivity analyses. The first was to repeat the above analyses, but using an exposure created by averaging Alu and LINE-1 methylation measurements weighted by their fractions of genome mass (11% and 17%, respectively, i.e., Alu methylation measurements would be weighted by 11 out of 28 and LINE-1 by 17 out of 28). Qualitatively the results were the same, with most statistical associations attenuated. Therefore, we opted not to report those results (data available upon request). For our second sensitivity analysis, we repeated the above regression models for Alu and LINE-1 measured at each individual position. As these results were not substantively different than those generated using the mean of these positions, we report the mean Alu and LINE-1 results only (data available upon request). All models were adjusted for the covariates listed above. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided tests were used when comparing means and β-coefficients, and P⩽0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Subject characteristics by cancer status have been reported previously (Zhu et al, 2011). Briefly, subjects were male, with a mean age of 72 years at first visit (range 55–100 years), and majority were white (95.5%). Characteristics by LINE-1 and Alu methylation at the first visit are listed in Table 1. Overall, there were no differences in subject characteristics by LINE-1 methylation. However, subjects with higher Alu methylation tended to have a higher BMI (P=0.022) than subjects with lower Alu methylation. The details of our LINE-1 and Alu methylation measurements by batch are provided in Table 2.

Table 3 shows the results of our first visit and time-dependent analyses. For cancer incidence, we found a positive association between risk of developing prostate cancer and LINE-1 methylation, which was significant in the time-dependent analysis (HR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.01–1.88). Alu methylation at the first measurement was directly associated with risk of developing respiratory cancer (HR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.09–3.78). For cancer mortality we found a positive association between risk of cancer mortality and LINE-1 methylation in time-dependent analysis (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.03–1.92), as well as Alu methylation at the first visit (HR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.08–1.79). In addition, Alu methylation at the first measurement was directly associated with risks of dying from digestive (HR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.06–2.29) and respiratory cancers (HR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.10–5.00). Results of our sensitivity analysis adjusting for batch as a covariate, rather than via standardisation, are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2 shows graphs of Alu and LINE-1 methylation by time interval between methylation measurement and cancer diagnosis. On average, subjects who ultimately developed cancer had LINE-1 methylation 0.54 units lower than cancer-free subjects, 10 or more years before diagnosis (P=0.0056). Neither the differences in mean LINE-1 methylation between cancer cases and cancer-free subjects at other time points were not significant, nor were the other differences in mean Alu methylation. The corresponding regression model results can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 4 shows the results of our rate of change analysis. We found significant associations between all-cancer incidence and the rate of change of Alu methylation (in standardised units per year; HR: 3.62, 95% CI: 1.09–12.10). We observed no significant associations between rate of change of LINE-1 methylation and cancer incidence. Neither Alu nor LINE-1 rate of change was associated with cancer mortality (data available upon request). Analysis of the rate of change of other cancers can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

In this study we found higher Alu methylation among participants who were younger and had lower BMI. For cancer incidence, time-dependent LINE-1 methylation was positively associated with risk of prostate cancer only. For cancer mortality, Alu methylation at the first blood draw as well as time-dependent LINE-1 methylation were associated with increased risk of all-cancer mortality. We identified associations between Alu methylation, and respiratory and digestive cancers, however, because of the small number of cases in these analyses our results should be interpreted cautiously. Interestingly, LINE-1 methylation was significantly lower in participants who ultimately developed cancer >10 years prior to conventional diagnosis, whereas a more rapid rate of increase in Alu methylation was significantly associated with risk of developing cancer. The updated results are different from our previous report (Zhu et al, 2011), which might be owing to the much larger number of incident cancer cases in our analysis (138 in our analysis vs 30 in the previous report), as well as our exclusion of prevalent cancers from the mortality analysis (leaving us with 37 deaths due to an incident cancer vs 11 in the previous report).

Although most studies of cancer, and Alu and LINE-1 methylation have found inverse relationships between these methylation measures and cancer, the vast majority of these findings have used tumour tissue, or blood leucocytes collected after cancer diagnosis (Brennan and Flanagan, 2012). Furthermore, two recent meta-analyses found that different measures of global DNA methylation in blood produce different associations with cancer risk, and that the methodological heterogeneity of studies makes drawing conclusions as to its use as a cancer biomarker difficult (Brennan and Flanagan, 2012; Woo and Kim, 2012). The findings of the handful of prospective studies of blood leucocyte Alu or LINE-1 methylation have thus far been less consistent. Three studies of gastric, liver, and breast cancer found no prospective associations between cancer risk and LINE-1 methylation (Balassiano et al, 2011; Brennan et al, 2012; Wu et al, 2012). In another prospective study, LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with breast cancer risk (Deroo et al, 2014), whereas two others found marginally significant associations between LINE-1 hypermethylation, and kidney (Karami et al, 2015) and bladder cancer (Andreotti et al, 2014). A prospective study of Alu methylation found an inverse association between Alu methylation and gastric cancer risk, but only with latencies of >1 year (Gao et al, 2012). These discrepant results are likely owing to high variation in study designs and populations (Brennan and Flanagan, 2012), such as the intervals between blood sample collection and cancer diagnosis, which ranged from 1 to 16 years in those cited above. A recent prospective analysis of prostate cancer patients found that the relationship between Alu methylation and prostate cancer risk varied by length of this interval, with associations between Alu hypermethylation and increased risk appearing only among subjects diagnosed 4 or more years after their blood draw (Barry et al, 2015). Although the effects of various intervals between blood sample collection and cancer diagnosis have not been studied in LINE-1 hypermethylation specifically, this effect may also explain our findings of increased prostate cancer risk with time-dependent LINE-1 methylation.

To our knowledge, few studies have examined associations between global DNA methylation of blood leucocytes collected pre-diagnostically and cancer mortality. Two studies found associations between serum LINE-1 hypomethylation and all-cause mortality in populations composed largely of cancer patients (Tangkijvanich et al, 2007; Ramzy et al, 2011), and our prior analysis of NAS data found associations between both LINE-1 and Alu hypomethylation and all-cancer mortality (Zhu et al, 2011). That our results represent a marked shift from the prior publication is cause for concern. We feel that this is primarily because of the fact that approximately half (59%) of cancer deaths in the previous study were due to cancers diagnosed prior to the first blood draw, potentially obscuring the temporal (and thus causal) relationship. The fact that our mortality analysis was conducted solely on participants who were free of cancer at the first blood draw may explain the discrepancy between our findings and those reported elsewhere in the literature examining cancer mortality among methylation measures obtained pre- and post-diagnosis. Future studies should further examine Alu and LINE-1 methylation as potential prognostic biomarkers for cancer mortality, and the differences in these relationships between methylation measures pre and post diagnosis.

Recent research suggests a dynamic role of Alu methylation during normal development and aging (Luo et al, 2014). Our analysis found a significant association between faster Alu methylation and higher cancer incidence, coupled with what is already known about the involvement of Alu methylation in tumourigenesis, this raises the possibility that Alu may have a dynamic role in cancer development as well. Similarly, we found that on average participants who would ultimately develop cancer had much lower LINE-1 methylation compared with cancer-free participants, but only at ∼10 years before diagnosis. Although both these findings are not unprecedented in this data set (Joyce et al, 2015), the low sample size of the NAS means that these results should be interpreted with caution. Further validation of these longitudinal biomarkers of cancer is required, but, if successful, could yield potent new tools for cancer early detection.

Although methylation of LINE-1 and Alu elements have both been widely used as surrogates for global DNA methylation, growing evidence shows that they each have a distinct functional role potentially affecting cancer development and progression via different mechanisms in methylation regulation, responses to cellular stressors and environmental exposures, and methylation levels (Li and Schmid, 2001; Jones and Baylin, 2002; Biemont and Vieira, 2006; Rusiecki et al, 2008). Even specific LINE-1 loci may exert different effects on disease risk (Nusgen et al, 2015; though there was no evidence for this in our particular data set). Thus, our finding different relationships between Alu and LINE-1 methylation and cancer is unsurprising, despite both being surrogates for global DNA methylation.

Our use of samples collected and stored before cancer diagnosis is a particular strength of this study as it avoids a number of biases inherent in case-control designs, particularly disease- or treatment-induced epigenetic changes. Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. The trade-off to collecting a large quantity of data across multiple follow-up measurements is a relatively low sample size. These factors limited our ability to examine specific subtypes of cancer beyond prostate cancer. In addition, as noted above, our sample was not representative of the general population. Being older, male, white, educated, and/or having a history of military service may all influence both global DNA methylation and cancer. Therefore, our results will need to be confirmed in other, more representative populations. Finally, it should be noted (as it has in both recent meta-analyses (Brennan and Flanagan, 2012; Barchitta et al, 2014) on the subject) that publication bias is a serious and unresolved concern for studies of Alu and LINE-1 methylation, and that care should be taken in the future to report null results.

In conclusion, this prospective study of global DNA methylation and cancer found a series of complex relationships underlying Alu and LINE-1 methylation, cancer incidence and mortality, and time. Alu and LINE-1 hypermethylation of blood leucocytes may be a predictor of cancer incidence, in particular prostate cancer. Furthermore, Alu and LINE-1 methylation may serve as useful prognostic indicators of cancer mortality. The possible use of these two measures as cancer early-detection and prognostic biomarkers, and whether such relationships are consistent with other measures of global DNA methylation, should be validated in larger prospective studies. In addition, the rate of change of Alu methylation and average LINE-1 methylation 10 years pre-diagnostically are interesting (if speculative) findings that need to be confirmed in future research. Taken together, these findings suggest that global DNA methylation has a dynamic role in tumourigenesis and cancer progression, and identify several new avenues of research for the study of Alu and LINE-1 as biomarkers of cancer.

Change history

09 August 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Andreotti G, Karami S, Pfeiffer RM, Hurwitz L, Liao LM, Weinstein SJ, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Silverman DT, Rothman N, Moore LE (2014) LINE1 methylation levels associated with increased bladder cancer risk in pre-diagnostic blood DNA among US (PLCO) and European (ATBC) cohort study participants. Epigenetics 9 (3): 404–415.

Babushok DV, Kazazian HH (2007) Progress in understanding the biology of the human mutagen LINE-1. Hum Mutat 28 (6): 527–539.

Balassiano K, Lima S, Jenab M, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Canzian F, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Meidtner K, Trichopoulou A, Laglou P, Vineis P, Panico S, Palli D, Grioni S, Tumino R, Lund E, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Numans ME, Peeters PH, Ramon Quiros J, Sanchez MJ, Navarro C, Ardanaz E, Dorronsoro M, Hallmans G, Stenling R, Ehrnstrom R, Regner S, Allen NE, Travis RC, Khaw KT, Offerhaus GJ, Sala N, Riboli E, Hainaut P, Scoazec JY, Sylla BS, Gonzalez CA, Herceg Z (2011) Aberrant DNA methylation of cancer-associated genes in gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Cancer Lett 311 (1): 85–95.

Barchitta M, Quattrocchi A, Maugeri A, Vinciguerra M, Agodi A (2014) LINE-1 hypomethylation in blood and tissue samples as an epigenetic marker for cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 9 (10): e109478.

Bariol C, Suter C, Cheong K, Ku SL, Meagher A, Hawkins N, Ward R (2003) The relationship between hypomethylation and CpG island methylation in colorectal neoplasia. Am J Pathol 162 (4): 1361–1371.

Barry KH, Moore LE, Liao LM, Huang WY, Andreotti G, Poulin M, Berndt SI (2015) Prospective study of DNA methylation at LINE-1 and Alu in peripheral blood and the risk of prostate cancer. Prostate 75 (15): 1718–1725.

Biemont C, Vieira C (2006) Genetics: junk DNA as an evolutionary force. Nature 443 (7111): 521–524.

Brennan K, Flanagan JM (2012) Is there a link between genome-wide hypomethylation in blood and cancer risk? Cancer Prev Res 5 (12): 1345–1357.

Brennan K, Garcia-Closas M, Orr N, Fletcher O, Jones M, Ashworth A, Swerdlow A, Thorne H, Riboli E, Vineis P, Dorronsoro M, Clavel-Chapelon F, Panico S, Onland-Moret NC, Trichopoulos D, Kaaks R, Khaw KT, Brown R, Flanagan JM (2012) Intragenic ATM methylation in peripheral blood DNA as a biomarker of breast cancer risk. Cancer Res 72 (9): 2304–2313.

Cravo M, Pinto R, Fidalgo P, Chaves P, Gloria L, Nobre-Leitao C, Costa Mira F (1996) Global DNA hypomethylation occurs in the early stages of intestinal type gastric carcinoma. Gut 39 (3): 434–438.

Das PM, Singal R (2004) DNA methylation and cancer. J Clin Oncol 22 (22): 4632–4642.

Deroo LA, Bolick SC, Xu Z, Umbach DM, Shore D, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP, Taylor JA (2014) Global DNA methylation and one-carbon metabolism gene polymorphisms and the risk of breast cancer in the Sister Study. Carcinogenesis 35 (2): 333–338.

Di JZ, Han XD, Gu WY, Wang Y, Zheng Q, Zhang P, Wu HM, Zhu ZZ (2011) Association of hypomethylation of LINE-1 repetitive element in blood leukocyte DNA with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 12 (10): 805–811.

Ehrlich M, Woods CB, Yu MC, Dubeau L, Yang F, Campan M, Weisenberger DJ, Long T, Youn B, Fiala ES, Laird PW (2006) Quantitative analysis of associations between DNA hypermethylation, hypomethylation, and DNMT RNA levels in ovarian tumors. Oncogene 25 (18): 2636–2645.

Gao Y, Baccarelli A, Shu XO, Ji BT, Yu K, Tarantini L, Yang G, Li HL, Hou L, Rothman N, Zheng W, Gao YT, Chow WH (2012) Blood leukocyte Alu and LINE-1 methylation and gastric cancer risk in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Br J Cancer 106 (3): 585–591.

Grover D, Mukerji M, Bhatnagar P, Kannan K, Brahmachari SK (2004) Alu repeat analysis in the complete human genome: trends and variations with respect to genomic composition. Bioinformatics 20 (6): 813–817.

Hansen KD, Timp W, Bravo HC, Sabunciyan S, Langmead B, McDonald OG, Wen B, Wu H, Liu Y, Diep D, Briem E, Zhang K, Irizarry RA, Feinberg AP (2011) Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nat Genet 43 (8): 768–775.

Hou L, Wang H, Sartori S, Gawron A, Lissowska J, Bollati V, Tarantini L, Zhang FF, Zatonski W, Chow WH, Baccarelli A (2010) Blood leukocyte DNA hypomethylation and gastric cancer risk in a high-risk Polish population. Int J Cancer 127 (8): 1866–1874.

Hou L, Zhang X, Tarantini L, Nordio F, Bonzini M, Angelici L, Marinelli B, Rizzo G, Cantone L, Apostoli P, Bertazzi PA, Baccarelli A (2011) Ambient PM exposure and DNA methylation in tumor suppressor genes: a cross-sectional study. Part Fibre Toxicol 8: 25.

Jones PA, Baylin SB (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 3 (6): 415–428.

Joyce BT, Gao T, Liu L, Zheng Y, Liu S, Zhang W, Penedo F, Dai Q, Schwartz J, Baccarelli AA, Hou L (2015) Longitudinal study of DNA methylation of inflammatory genes and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24 (10): 1531–1538.

Karami S, Andreotti G, Liao LM, Pfeiffer RM, Weinstein SJ, Purdue MP, Hofmann JN, Albanes D, Mannisto S, Moore LE (2015) LINE1 methylation levels in pre-diagnostic leukocyte DNA and future renal cell carcinoma risk. Epigenetics 10 (4): 282–292.

Kazazian HH Jr, Goodier JL (2002) LINE drive. retrotransposition and genome instability. Cell 110 (3): 277–280.

Kochanek S, Renz D, Doerfler W (1993) DNA methylation in the Alu sequences of diploid and haploid primary human cells. EMBO J 12 (3): 1141–1151.

Laird PW (2005) Cancer epigenetics. Hum Mol Genet 14 (Spec No 1): R65–R76.

Li TH, Schmid CW (2001) Differential stress induction of individual Alu loci: implications for transcription and retrotransposition. Gene 276 (1-2): 135–141.

Liao LM, Brennan P, van Bemmel DM, Zaridze D, Matveev V, Janout V, Kollarova H, Bencko V, Navratilova M, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Mates D, Rothman N, Boffetta P, Chow WH, Moore LE (2011) LINE-1 methylation levels in leukocyte DNA and risk of renal cell cancer. PloS One 6 (11): e27361.

Lim U, Flood A, Choi SW, Albanes D, Cross AJ, Schatzkin A, Sinha R, Katki HA, Cash B, Schoenfeld P, Stolzenberg-Solomon R (2008) Genomic methylation of leukocyte DNA in relation to colorectal adenoma among asymptomatic women. Gastroenterology 134 (1): 47–55.

Luo Y, Lu X, Xie H (2014) Dynamic Alu methylation during normal development, aging, and tumorigenesis. BioMed Res Int 2014: 784706.

Moore LE, Pfeiffer RM, Poscablo C, Real FX, Kogevinas M, Silverman D, Garcia-Closas R, Chanock S, Tardon A, Serra C, Carrato A, Dosemeci M, Garcia-Closas M, Esteller M, Fraga M, Rothman N, Malats N (2008) Genomic DNA hypomethylation as a biomarker for bladder cancer susceptibility in the Spanish Bladder Cancer Study: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 9 (4): 359–366.

Neale RE, Clark PJ, Fawcett J, Fritschi L, Nagler BN, Risch HA, Walters RJ, Crawford WJ, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Buchanan DD (2014) Association between hypermethylation of DNA repetitive elements in white blood cell DNA and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 38 (5): 576–582.

Nusgen N, Goering W, Dauksa A, Biswas A, Jamil MA, Dimitriou I, Sharma A, Singer H, Fimmers R, Frohlich H, Oldenburg J, Gulbinas A, Schulz WA, El-Maarri O (2015) Inter-locus as well as intra-locus heterogeneity in LINE-1 promoter methylation in common human cancers suggests selective demethylation pressure at specific CpGs. Clinical Epigenet 7 (1): 17.

Ohgane J, Yagi S, Shiota K (2008) Epigenetics: the DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions in cells. Placenta 29 (Suppl A): S29–S35.

Pufulete M, Al-Ghnaniem R, Leather AJ, Appleby P, Gout S, Terry C, Emery PW, Sanders TA (2003) Folate status, genomic DNA hypomethylation, and risk of colorectal adenoma and cancer: a case control study. Gastroenterology 124 (5): 1240–1248.

Ramzy II, Omran DA, Hamad O, Shaker O, Abboud A (2011) Evaluation of serum LINE-1 hypomethylation as a prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Arab J Gastroenterol 12 (3): 139–142.

Rusiecki JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V, Tarantini L, Moore LE, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC (2008) Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with high serum-persistent organic pollutants in Greenlandic Inuit. Environ Health Perspect 116 (11): 1547–1552.

Schmid CW (1998) Does SINE evolution preclude Alu function? Nucleic Acids Res 26 (20): 4541–4550.

Soares J, Pinto AE, Cunha CV, Andre S, Barao I, Sousa JM, Cravo M (1999) Global DNA hypomethylation in breast carcinoma: correlation with prognostic factors and tumor progression. Cancer 85 (1): 112–118.

Tajuddin SM, Amaral AF, Fernandez AF, Chanock S, Silverman DT, Tardon A, Carrato A, Garcia-Closas M, Jackson BP, Torano EG, Marquez M, Urdinguio RG, Garcia-Closas R, Rothman N, Kogevinas M, Real FX, Fraga MF, Malats N (2014) LINE-1 methylation in leukocyte DNA, interaction with phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase variants and bladder cancer risk. Br J Cancer 110 (8): 2123–2130.

Tangkijvanich P, Hourpai N, Rattanatanyong P, Wisedopas N, Mahachai V, Mutirangura A (2007) Serum LINE-1 hypomethylation as a potential prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta 379 (1-2): 127–133.

Van Hoesel AQ, Van De Velde CJH, Kuppen PJK, Liefers GJ, Putter H, Sato Y, Elashoff DA, Turner RR, Shamonki JM, De Kruijf EM, Van Nes JGH, Giuliano AE, Hoon DSB (2012) Hypomethylation of LINE-1 in primary tumor has poor prognosis in young breast cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134 (3): 1103–1114.

Walters RJ, Williamson EJ, English DR, Young JP, Rosty C, Clendenning M, Walsh MD, Parry S, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Win AK, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA, Buchanan DD (2013) Association between hypermethylation of DNA repetitive elements in white blood cell DNA and early-onset colorectal cancer. Epigenetics 8 (7): 748–755.

Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Long TI, Kim M, Woods C, Fiala E, Ehrlich M, Laird PW (2005) Analysis of repetitive element DNA methylation by MethyLight. Nucleic Acids Res 33 (21): 6823–6836.

Wilson AS, Power BE, Molloy PL (2007) DNA hypomethylation and human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1775 (1): 138–162.

Woo HD, Kim J (2012) Global DNA hypomethylation in peripheral blood leukocytes as a biomarker for cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PloS One 7 (4): e34615.

Wu HC, Wang Q, Yang HI, Tsai WY, Chen CJ, Santella RM (2012) Global DNA methylation levels in white blood cells as a biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a nested case-control study. Carcinogenesis 33 (7): 1340–1345.

Yang AS, Estecio MR, Doshi K, Kondo Y, Tajara EH, Issa JP (2004) A simple method for estimating global DNA methylation using bisulfite PCR of repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res 32 (3): e38.

Zhu ZZ, Sparrow D, Hou L, Tarantini L, Bollati V, Litonjua AA, Zanobetti A, Vokonas P, Wright RO, Baccarelli A, Schwartz J (2011) Repetitive element hypomethylation in blood leukocyte DNA and cancer incidence, prevalence, and mortality in elderly individuals: the Normative Aging Study. Cancer Causes Control 22 (3): 437–447.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ziff Fund at the Harvard University Center for the Environment, NIEHS grants RO1-ES015172, 2RO1-ES015172, and ES014663. The Normative Aging Study is supported by the Cooperative Studies Program/Epidemiology Research and Information Center of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and is a component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center, Boston, MA, USA. In addition, this publication was made possible by USEPA grant RD-832416 and RD-83479801. LH received additional support from the Northwestern University Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center Rosenberg Research Fund. AB and JS received additional support from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS R01-ES021733, NIEHS R01-ES015172, and NIEHS P30-ES00002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Disclaimer

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USEPA. Further, USEPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication.

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Joyce, B., Gao, T., Zheng, Y. et al. Prospective changes in global DNA methylation and cancer incidence and mortality. Br J Cancer 115, 465–472 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.205

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.205

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinal study of leukocyte DNA methylation and biomarkers for cancer risk in older adults

Biomarker Research (2019)

-

Endogenous sex hormone exposure and repetitive element DNA methylation in healthy postmenopausal women

Cancer Causes & Control (2017)