Abstract

Background:

Limited data suggest that statin use reduces the risk for ovarian cancer.

Methods:

Using Danish nationwide registries, we identified 4103 cases of epithelial ovarian cancer during 2000–2011 and age-matched them to 58 706 risk-set sampled controls. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for epithelial ovarian cancer overall, and for histological types, associated with statin use.

Results:

We observed a neutral association between ever use of statins and epithelial ovarian cancer risk (OR=0.98, 95% CI=0.87–1.10), and no apparent risk variation according to duration, intensity or type of statin use. Decreased ORs associated with statin use were seen for mucinous ovarian cancer (ever statin use: OR=0.63, 95% CI=0.39–1.00).

Conclusions:

Statin use was not associated with overall risk for epithelial ovarian cancer. The inverse association between statin use and mucinous tumours merits further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Identification of protective factors against ovarian cancer has huge public health implications, as this gynaecological cancer continues to have a sinister prognosis (Klint et al, 2010).

It has been suggested that statins protect against the development of cancer, including ovarian cancer (Boudreau et al, 2010). Experimental studies of human cancer cell lines and animal tumour models have demonstrated that statins induce apoptosis (Liu et al, 2009; Matsuura et al, 2011), inhibit angiogenesis (Chen et al, 2012) and suppress tumour growth and metastases (Alonso et al, 1998). Secondary analyses of randomised clinical trials of statin use and coronary heart disease have not had adequate statistical precision to evaluate comprehensively the association between statin use and ovarian cancer risk (Dale et al, 2006), and only four observational studies have specifically reported on the risk for ovarian cancer associated with statin use (Kaye and Jick, 2004; Friedman et al, 2008; Yu et al, 2009; Lavie et al, 2013). This prompted us to examine the association between statin use and ovarian cancer risk in a large nationwide case–control study.

Materials and Methods

Study population and record linkage

Our case–control study was nested in the entire Danish female population (population, 2.8 million), using data from seven nationwide registries. The registries were linked by use of the unique civil registration number assigned to all Danish citizens by the Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011). From the Danish Cancer Registry (Gjerstorff, 2011), we identified all women aged 30–84 years with a histologically verified first diagnosis of well-defined epithelial ovarian cancer during 2000–2011. We required that the cases were resident in Denmark at the start of the Prescription Registry in 1995 and at the date of diagnosis, defined as the index date. We also required the cases to have no history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) before the index date. For each case, we randomly selected 15 age-matched female population controls using risk-set sampling and applying the same selection criteria as for the cases (Rothman et al, 2008; Pedersen, 2011). In addition, we required that the controls have no bilateral oophorectomy before the index date.

All statin (ATC code C10AA) prescriptions redeemed by the cases and controls between January 1995 and 1 year before the index date were obtained from the Danish Prescription Registry (Kildemoes et al, 2011). We defined ‘ever use’ of statin as ⩾2 prescriptions on separate dates and ‘non-use’ as <2 prescriptions. The duration of statin use was defined as the time between the first and last redeemed statin prescription plus 60 days and classified as short-term (<5 years) or long-term (⩾5 years). The intensity of use was defined as the cumulative number of defined daily doses (DDDs) (WHO, 2010) of statins divided by the duration of use in days and classified into approximate tertiles of low, medium or high intensity. Finally, we categorised statins by their lipid solubility into either ‘exclusive use of lipophilic statins’ (simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin) or ‘ever use of hydrophilic statins’ (pravastatin and rosuvastatin).

Statistical analysis

We used conditional logistic regression to estimate age- and multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for ovarian cancer associated with the use of statins. The reference group in all analyses was non-use of statins. Confounding factors were selected a priori and included age, parity, infertility, endometriosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, hysterectomy, tubal sterilisation, education, income, and the use of oral contraceptives, hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), paracetamol and low-dose aspirin. We stratified analyses according to duration and intensity of statin use and tested the combined exposure categories of duration and intensity for trend. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R, version 3.0.2 (R Development Core Team, 2013).

A further description of the included registries, codes for identification of cases, drug use and other characteristics, and additional analyses are provided in the Supplementary text and Supplementary Table 1.

Results

We identified 4103 epithelial ovarian cancer cases (2731 serous, 650 endometrioid, 459 mucinous and 263 clear cell) and 58 706 controls. Only slight differences in characteristics were observed between the cases and controls (Table 1). The prevalence of ever use of statins was similar among cases (10.6%) and controls (11.0%). The vast majority of statin users were exclusive users of lipophilic statins (87.6%).

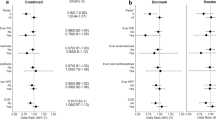

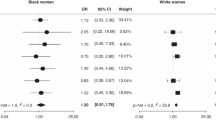

Ever use of statins was not associated with risk for overall epithelial (OR=0.98, 95% CI=0.87–1.10) or serous (OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.90–1.19) ovarian cancer (Table 2). No material risk variation was observed with increasing duration or intensity of statin use, and we found no apparent trends with the intensity of use within strata of short-term (epithelial overall: P trend=0.22; serous: P trend=0.98) or long-term (epithelial overall: P trend=0.68; serous: P trend=0.78) statin use (Table 2).

In analyses of histological types of epithelial ovarian cancer, inverse associations were observed between ever use of statins and risk for endometrioid (OR=0.80, 95% CI=0.58–1.10) and, notably, mucinous tumours (OR=0.63, 95% CI=0.39–1.00). In contrast, we observed an elevated OR for clear cell ovarian cancer (OR=1.48, 95% CI=0.92–2.38) associated with ever statin use. Albeit based on small numbers, reduced ORs were observed for mucinous ovarian cancer with short-term (OR=0.57, 95% CI=0.33–0.96) or high-intensity (OR=0.23, 95% CI=0.07–0.74) statin use. High-intensity statin use was also associated with a reduced OR for endometrioid ovarian cancer (OR=0.54, 95% CI=0.30–0.96), whereas elevated ORs were found for clear cell ovarian cancer in all exposure categories, and notably ⩾5 years of statin use (OR=2.05, 95% CI=0.98–4.29).

Restricting the overall analyses to use of lipophilic statins exclusively yielded risk estimates close to those in the main analysis (presented in Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

Our large population-based case–control study did not support an association between statin use and risk for overall epithelial or serous ovarian cancer, and we observed no variation in risk for these cancers according to duration, intensity or lipophilicity of statin use. With respect to non-serous types of epithelial ovarian cancer, we found inverse associations between statin use and risks for mucinous and endometrioid tumours, whereas the risk estimates were increased for clear cell ovarian cancer. The inverse associations between statin use and mucinous and endometrioid ovarian cancer were largest for high-intensity statin use, whereas risk estimates for clear cell ovarian cancer increased with the duration of statin use; however, the results for non-serous tumours were based on small numbers, and our study did not allow full evaluation of the influence of statin use on risks for these types of ovarian cancer.

Our findings for epithelial ovarian cancer are compatible with those reported by Kaye et al (2004) in a population-based case–control study based on prescription data in the General Practice Research Database. Three other register-based studies (Friedman et al, 2008; Yu et al, 2009; Lavie et al, 2013) reported statistically non-significant inverse associations between statin use and ovarian cancer risk, and a recent meta-analysis (Liu et al, 2014) of the previous studies suggested an inverse relationship between increasing duration of statin use and ovarian cancer risk. In our study; however, we found no risk variation according to the duration of statin use and our evaluation of the risk for epithelial and serous ovarian cancer according to both duration and intensity of use also did not reveal any dose–response patterns.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to report on the association between statin use and specific histological types of epithelial ovarian cancer. Due to the heterogeneous biology of epithelial ovarian cancer (Risch et al, 1996; Kurman and Shih, 2010), any antineoplastic effect of statin use would conceivably vary between individual histological types. We have no ready explanation for the consistent increase in clear cell ovarian cancer in nearly all categories of statin use. In contrast, some evidence may support our finding of an inverse association between statin use and mucinous ovarian cancer as mucinous tumours differ from non-mucinous types of epithelial ovarian cancer with regard to several risk factors (Risch et al, 1996; Soegaard et al, 2007) and tissue of origin (Kurman and Shih, 2010).

In line with the results of a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (Dale et al, 2006), we found no apparent difference in the risk estimates according to the lipophilicity of statins. Other pharmacodynamic aspects include the hepatoselectivity and large hepatic first-pass effect of statins leading to low systemic bioavailability (Gazzerro et al, 2012). Thus, the serum levels of statins during the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia may not be sufficiently high to achieve antineoplastic effects. This might explain the discrepancy between the results of observational studies and those of experimental studies demonstrating apparent antineoplastic effects of statins (Liu et al, 2009; Matsuura et al, 2011).

Our study had several strengths. First, it is the largest of the association between statin use and ovarian cancer risk. Moreover, information was derived from national registries of high quality with complete coverage on all Danish residents. As statins are available only by prescription in Denmark, we captured all statin use from 1995, and the register-based design eliminated selection or recall bias. Furthermore, the distribution of ovarian cancer risk factors among cases and controls were compatible with the literature, providing further reassurance about study validity.

Our study also had limitations. Information on drug use before 1995 was not available, raising a possibility of left truncation prescription data bias. However, the impact of exposure truncation was likely minimal for statins as the use of these agents was limited in Denmark until the mid-1990s (Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group, 1994; Riahi et al, 2001). Non-compliance constituted another source of exposure misclassification. However, we believe that non-compliance had little impact on our results as we defined statin use as ⩾2 prescriptions redeemed on separate dates and the prescription records are based on drugs that are actually purchased at pharmacies (only part of the cost of drugs is reimbursed in Denmark). Adherence to preventive drug therapy is known to be associated with behaviour for improving or maintaining health, that is, the healthy-user effect (Dormuth et al, 2009). Although we evaluated the potential confounding effect of socioeconomic status by adjusting for education and income, we had no information on health-seeking behaviour, such as regular gynaecological examinations, and we cannot rule out potentially important residual confounding by this or other unmeasured factors associated with both statin use and ovarian cancer risk. Finally, our exposure period might have been too short and the statistical precision in estimates of long-term statin exposure too low to appropriately assess the influence of statin use on ovarian cancer risk.

In conclusion, statin use was not associated with risk for overall epithelial or serous ovarian cancer in our study, and we found no consistent trend in ovarian cancer risk with increasing duration or intensity of statin use. Our observation of an inverse association between statin use and risk for mucinous ovarian cancer may be a chance finding; however, as mucinous cancers differ from the other ovarian cancer types in many respects, this finding may warrant further investigation.

Change history

06 January 2015

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Alonso DF, Farina HG, Skilton G, Gabri MR, De Lorenzo MS, Gomez DE (1998) Reduction of mouse mammary tumor formation and metastasis by lovastatin, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 50: 83–93.

Boudreau DM, Yu O, Johnson J (2010) Statin use and cancer risk: a comprehensive review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 9: 603–621.

Chen J, Liu B, Yuan J, Yang J, Zhang J, An Y, Tie L, Pan Y, Li X (2012) Atorvastatin reduces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in human non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs) via inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Mol Oncol 6: 62–72.

Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, Kluger J, White CM (2006) Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. JAMA 295: 74–80.

Dormuth CR, Patrick AR, Shrank WH, Wright JM, Glynn RJ, Sutherland J, Brookhart A (2009) Statin adherence and risk of accidents: a cautionary tale. Circulation 119: 2051–2057.

Friedman GD, Flick ED, Udaltsova N, Chan J, Quesenberry CP Jr., Habel LA (2008) Screening statins for possible carcinogenic risk: up to 9 years of follow-up of 361,859 recipients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 17: 27–36.

Gazzerro P, Proto MC, Gangemi G, Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Pisanti S, Santoro A, Laezza C, Bifulco M (2012) Pharmacological actions of statins: a critical appraisal in the management of cancer. Pharmacol Rev 64: 102–146.

Gjerstorff ML (2011) The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health 39 (7 Suppl): 42–45.

Kaye JA, Jick H (2004) Statin use and cancer risk in the General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer 90: 635–637.

Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J (2011) The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 39 (7 Suppl): 38–41.

Klint A, Tryggvadottir L, Bray F, Gislum M, Hakulinen T, Storm HH, Engholm G (2010) Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with cancer in female genital organs in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol 49: 632–643.

Kurman RJ, Shih I (2010) The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 34: 433–443.

Lavie O, Pinchev M, Rennert HS, Segev Y, Rennert G (2013) The effect of statins on risk and survival of gynecological malignancies. Gynecol Oncol 130: 615–619.

Liu H, Liang SL, Kumar S, Weyman CM, Liu W, Zhou A (2009) Statins induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells through activation of JNK and enhancement of Bim expression. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 63: 997–1005.

Liu Y, Qin A, Li T, Qin X, Li S (2014) Effect of statin on risk of gynecologic cancers: a meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Oncol 133: 647–655.

Matsuura M, Suzuki T, Suzuki M, Tanaka R, Ito E, Saito T (2011) Statin-mediated reduction of osteopontin expression induces apoptosis and cell growth arrest in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep 25: 41–47.

Pedersen CB (2011) The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 39 (7 Suppl): 22–25.

R Development Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria.

Riahi S, Fonager K, Toft E, Hvilsted-Rasmussen L, Bendsen J, Paaske JS, Soerensen HT (2001) Use of lipid-lowering drugs during 1991–98 in Northern Jutland, Denmark. Br J Clin Pharmacol 52: 307–311.

Risch HA, Marrett LD, Jain M, Howe GR (1996) Differences in risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer by histologic type. Results of a case–control study. Am J Epidemiol 144: 363–372.

Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Modern epidemiology. Wolters Kluwer Health 3rd edn Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group (1994) Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 344: 1383–1389.

Soegaard M, Jensen A, Hogdall E, Christensen L, Hogdall C, Blaakaer J, Kjaer SK (2007) Different risk factor profiles for mucinous and nonmucinous ovarian cancer: results from the Danish MALOVA study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 1160–1166.

WHO (2010) Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC Classification and DDDs Assignment 2011: Oslo, Norway.

Yu O, Boudreau DM, Buist DS, Miglioretti DL (2009) Statin use and female reproductive organ cancer risk in a large population-based setting. Cancer Causes Control 20: 609–616.

Acknowledgements

Funding was obtained from Unit of Lifestyle, Virus and Genes, Danish Cancer Society Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Baandrup, L., Dehlendorff, C., Friis, S. et al. Statin use and risk for ovarian cancer: a Danish nationwide case–control study. Br J Cancer 112, 157–161 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.574

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.574

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Use of statins and risks of ovarian, uterine, and cervical diseases: a cohort study in the UK Biobank

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2024)

-

Ovary and uterus related adverse events associated with statin use: an analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies assessing the relationship between statin use and risk of ovarian cancer

Cancer Causes & Control (2020)

-

Statin use and the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers: a meta-analysis

BMC Cancer (2019)

-

DNAJA1 controls the fate of misfolded mutant p53 through the mevalonate pathway

Nature Cell Biology (2016)