Abstract

Background:

We conducted a population-based cohort study to assess whether tamoxifen treatment is associated with an increased incidence of diabetes.

Methods:

Data obtained from the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database were used for a population-based cohort study. The study cohort included 22 257 breast cancer patients diagnosed between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2004. Among them, 15 210 cases received tamoxifen treatment and 7047 did not. Four subjects without breast cancer were frequency-matched by age and index year as the control group. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Results:

Breast cancer patients exhibited a 14% higher rate of developing diabetes (adjusted HR=1.14, 95% CI=1.08–1.20) compared with non-breast cancer controls, but the significant difference was limited to tamoxifen users. In addition, tamoxifen users exhibited a significantly increased risk of diabetes compared with non-tamoxifen users among women diagnosed with breast cancer (adjusted HR=1.31, 95% CI=1.19–1.45). Stratification by age groups indicated that both younger and older women diagnosed with breast cancer exhibited a significantly higher risk of diabetes than the normal control subjects did, and tamoxifen users consistently exhibited a significantly higher diabetes risk than non-tamoxifen users or normal control subjects did, regardless of age. Both recent and remote uses of tamoxifen were associated with an increased likelihood of diabetes.

Conclusions:

The results of this population-based cohort study suggested that tamoxifen use in breast cancer patients might increase subsequent diabetes risk. The underlying mechanism remains unclear and further larger studies are mandatory to validate our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Both cancer and diabetes are common diseases worldwide. According to the 2012 statistics of the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, cancer and diabetes are the first and fifth leading causes of death, respectively (Department of Health, Taiwan, 2012). Breast cancer has been the most common type of cancer diagnosed among women in Taiwan since 1996. The age-adjusted incidence rate has increased steadily, and it reached 74.63 new cases per 100 000 people in 2011 (Cancer Statistics Annual Report, 2014). The relationship between diabetes and breast cancer has been widely studied, but most studies have focused on the breast cancer risk among diabetes patients and have revealed that diabetes is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Larsson et al, 2007; La Vecchia et al, 2011; Cleveland et al, 2012; Hardefeldt et al, 2012). Conversely, studies exploring the potential of a reverse relationship (i.e., subsequent development of diabetes after the diagnosis of breast cancer) have been limited (Lipscombe et al, 2006; Bordeleau et al, 2011; Lipscombe et al, 2012). A previous Canadian cross-sectional study revealed that the prevalence of newly diagnosed diabetes is increased among prior breast cancer patients (Lipscombe et al, 2006). In another nested case–control study, the authors observed that current tamoxifen therapy is associated with an increased incidence of diabetes in older breast cancer patients (Lipscombe et al, 2012).

Tamoxifen is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator and binds to oestrogen receptor as partial agonist or antagonist in a manner depending on target tissue (Yeh et al, 2014). It is one of the most widely used hormonal therapies and has proven effective in both early and advanced stages of breast cancer (MacGregor and Jordan, 1998). More than 67% of breast cancers have been reported as being sensitive to tamoxifen therapy (Rakha et al, 2007; Yang et al, 2012). In general, tamoxifen therapy is relatively tolerable with a fair adherence rate (Wigertz et al, 2012). The well-documented side effects of tamoxifen include thromboembolism, symptoms of menopause, and endometrial cancer (McCarthy, 2004; Amir et al, 2011; Lipscombe et al, 2012). The risk of diabetes and tamoxifen use might plausibly be linked based on the observation of the oestrogen inhibition effect of tamoxifen and interactive roles of insulin and oestrogen (Bryzgalova et al, 2006; Lundholm et al, 2008; Rondini et al, 2011).

Based on a review of the literature, no data are available on tamoxifen use and diabetes risk in premenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer. We conducted this population-based cohort study to determine the possible association of tamoxifen and diabetes among Asian female breast cancer patients aged 20 years or older.

Materials and Methods

Data source

The National Health Insurance (NHI) Programme was established in Taiwan in 1995, and it covers ∼99% of the Taiwanese population and contracts with 97% of hospitals as well as 92% of clinics nationwide (department of health). The National Health Research Institutes maintains the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) and releases it annually to the public for research purposes. In this study, we used the registry for Catastrophic Illnesses Patient Database (CIPD). The NHI programme includes a catastrophic illness programme, in which insurants diagnosed with major diseases, such as cancers, chronic mental illness, and several autoimmune diseases, can enrol. The CIPD contains medical information including inpatient and outpatient care facilities, drug prescriptions, sex, date of birth, dates of visits or hospitalisations, and diagnoses coded in the format of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of China Medical University (CMU-REC-101-012).

Study cohorts

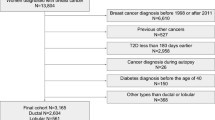

In this cohort study, we selected 22 257 women aged 20 years or older, newly diagnosed with breast cancer (ICD-9-CM code 174) during the period of 2000–2004, from the CIPD as the case group, which was divided into two groups based on tamoxifen use status. Among them, 15 210 patients used tamoxifen and 7047 did not. The index date for each patient was the first prescription of tamoxifen. For each case patient, four control women were selected to form the control group, who were frequency-matched for age (in 5-year age bands) and index year. A total of 89 028 subjects formed the cancer-free healthy control group. All participants with a history of type 2 diabetes or cancer before index the date were excluded from this analysis. They were followed up until they were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250.x2), or until the participants were censored because of loss to follow-up, withdrawal from the NHI system, or the end of 2011.

The sociodemographic factors studied included age and insured amount. Age was categorised into two levels: 20–54 and ⩾55 (in years). Amount of insurance premium was categorised into three levels: <15 000, 15 000–29 999, and ⩾30 000 New Taiwan dollars per month. We obtained records of comorbidities before the index date. The insurance premium amount of an individual was determined by her work salary. The comorbidities included coronary artery disease (CAD; ICD-9-CM codes 410–414), congestive heart failure (ICD-9-CM code 428), stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430–438), hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), and hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), which were potential confounders in the association between breast cancer and type 2 diabetes. Patients used steroids, thiazide diuretics, and statins before enrolment may influence glucose metabolism, and the information was also reviewed from the database.

Statistical analysis

We used chi-square test and t-test to compare the distributions of age (20–54 and ⩾55 years) and comorbidities between the case and control groups. Survival analysis was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and significance was determined using log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression model to assess the independent effect of tamoxifen treatment by adjusting for the other variables in the model. We also evaluated the effect of duration of tamoxifen therapy (⩽180 and >180 days) on risk of type 2 diabetes among patients with breast cancer. All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS software Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.), and significance was determined by a two-tailed P-value <0.05.

Results

Baseline demographic factors and comorbidities of study participants are listed in Table 1, according to breast cancer status. The study included a cohort containing 22 257 women patients with breast cancer and 89 028 women individuals without cancer with a similar average age (50 years). Of these, 5079 and 7879 subjects were lost to follow-up in the breast cancer group and control group, respectively. Compared with the subjects without breast cancer, the patients with breast cancer exhibited a higher prevalence of lower insured amount (45.31% vs 20.05%), use of steroids (53.05% vs 47.65%), thiazide diuretics (16.20% vs 15.59%), and statins (5.24% vs 4.37%), and a lower prevalence of CAD (10.20% vs 10.72%), stroke (1.19% vs 1.40%), and hyperlipidemia (13.78% vs 14.39%). Overall, the median follow-up years were 7.73 years (range 0.002–11.98 years) in the breast cancer cohort and 7.73 years (range 0.002–11.96 years) in the non-cancer cohort.

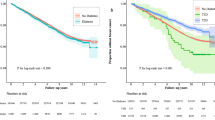

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated that patients with breast cancer exhibited significantly higher risk of type 2 diabetes than the cancer-free healthy control subjects did (log-rank test, P<0.001; Figure 1). Among breast cancer survivors, tamoxifen treatment was significantly associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes (log-rank test, P=0.01; Figure 2). The incidence rate of type 2 diabetes was higher in the cohort of breast cancer than that in the control group (13.13 vs 11.38 per 1000 person-years), with a HR of 1.14 (95% CI=1.08–1.20) when adjusting for age, insured amount, comorbidities, steroids, thiazide diuretics, and statins (Table 2). Among breast cancer patients, only tamoxifen users exhibited a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes compared with the control group. In addition, a statistically significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes was observed in breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen treatment compared with those without tamoxifen treatment (adjusted HR=1.31, 95% CI=1.19–1.45). After age stratification, we observed that both younger (20–54 years) and older (⩾55 years) age groups of breast cancer patients exhibited a significantly higher risk of diabetes than the control group did, but the significant findings were limited to tamoxifen users. When we focused on breast cancer patients, both age groups of tamoxifen users exhibited a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes compared with their counterparts without tamoxifen treatment (Table 3).

Compared with breast cancer patients without using tamoxifen, both breast cancer patient groups with ⩽180 and >180 days of tamoxifen therapy had significantly higher risks of type 2 diabetes, as shown in Table 4 (adjusted HR=2.12, 95% CI=1.83–2.44 and adjusted HR=1.20, 95% CI=1.08–1.33, respectively). Furthermore, we divided the breast cancer cohort into two subgroups according to aromatase inhibitor treatment to examine the combination effects of tamoxifen therapy and aromatase inhibitor treatment. We observed that only patients using tamoxifen-alone treatment had a significantly higher risk of type 2 diabetes than those without using tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor treatment (adjusted HR=1.32, 95% CI=1.19–1.47). By contrast, patients with aromatase inhibitor treatment (regardless of tamoxifen use or not) had significantly lower risks of type 2 diabetes than those without any hormone treatment, as shown in Table 5.

Discussion

In this population-based study, we observed a significant 14% increased rate of developing diabetes in breast cancer survivors compared with non-breast cancer control subjects, but the significant difference was only observed in tamoxifen users. When we focused on breast cancer survivors, the adjusted analysis still revealed that tamoxifen group had a significantly increased risk of diabetes compared with the non-tamoxifen group. Our data highlight developing diabetes as a possible side effect of tamoxifen use.

Previous studies have suggested that diabetes is an independent risk factor for breast cancer (Larsson et al, 2007; La Vecchia et al, 2011; Cleveland et al, 2012; Hardefeldt et al, 2012). Conversely, few researchers have considered the reverse hypothesis that breast cancer patients have a higher risk of developing subsequent diabetes. Lipscombe et al first explored the prevalence of breast cancer in the prediabetes phase through a cross-sectional study and observed an increased prevalence of prior breast cancer in women with newly diagnosed diabetes. They concluded that breast cancer prevalence is increased in women who subsequently develop diabetes, supporting the hypothesis that insulin resistance promotes breast cancer in the prediabetes phase (Lipscombe et al, 2006). Bordeleau et al (2011) observed that after a diagnosis of breast cancer, women exhibiting BRCA1 or BRCA2 faced a two-fold increase in the risk of diabetes. However, these highly selected patients were genetically predisposed to breast cancer and were more likely to be younger at diagnosis. A recent population-based retrospective cohort study focused on postmenopausal (⩾55 years) breast cancer survivors and highlighted a modest increase in the incidence of diabetes among this group (Lipscombe et al, 2013). We enrolled both premenopausal and postmenopausal women and observed a significant 14% increased rate of developing diabetes in breast cancer survivors compared with non-breast cancer control women as an entire age group. Figure 1 indicates that the risk of diabetes among women diagnosed with breast cancer increased gradually over time, which is consistent with a previous study (Lipscombe et al, 2013). To ensure an appropriate comparison with that study, we set the cut-off point at 55 years. Our results indicated that both younger and older women diagnosed with breast cancer were at higher risks than normal control subjects of developing diabetes. In addition to breast cancer, researchers have also considered the possibility that treatment of breast cancer might also promote diabetes. Another study revealed that tamoxifen therapy administered to older breast cancer survivors was associated with a significantly increased risk of diabetes (Lipscombe et al, 2012).

Tamoxifen was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States in 1977 for the treatment of women diagnosed with advanced breast cancer and several years later for the adjuvant treatment of primary breast cancer (Osborne, 1998). Because it is the most commonly prescribed hormone therapy for breast cancer patients (Goldhirsch et al, 2005), a low hazard–benefit ratio might have crucial clinical implications. This would be of interest to both the public and the medical profession. A large population-based study might clarify this uncertainty. Therefore, we conducted the current study to identify a relationship between tamoxifen use and diabetes risk.

Our analyses indicated that tamoxifen users were at a higher risk of developing diabetes compared with breast cancer patients who were not prescribed tamoxifen, regardless of age. This finding is partially consistent with the nested case–control study of Lipscombe et al (2012), who investigated women older than 65 years diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and observed that the current or recent past use of tamoxifen was associated with an increased incidence of diabetes in older patients, but remote use of tamoxifen (defined in their study as >180 days but <5 years) was not associated with an increased likelihood of diabetes. Our study showed that tamoxifen users exhibited a significantly increased risk of diabetes when compared with subjects without breast cancer in both younger and older groups. In addition, both recent and remote uses of tamoxifen were associated with significantly higher risks of diabetes. The possibility that diabetes predisposes to breast cancer or that a common underlying factor may predispose to both diabetes and breast cancer is an issue which needs to be considered; however, it is less likely because Figure 2 illustrates increased diabetes risk for tamoxifen users among women diagnosed with breast cancer over time.

Increased diabetes risk among tamoxifen users may be an oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer effect rather than a tamoxifen effect. To clarify this concern, we did a further analysis of joint effects of tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor and found that only tamoxifen-alone group had a significantly increased risk. In fact, aromatase inhibitor seems to play a protective role in the development of diabetes among breast cancer patients, but further exploration of it is out of our current investigation. The underlying mechanisms of the possible link between tamoxifen use and diabetes risk remain unclear. It is plausible to assume that because oestrogen has been suggested to play a role in blood sugar control (Godsland, 2005; Bryzgalova et al, 2006; Lundholm et al, 2008; Liu and Mauvais-Jarvis, 2009; Tiano and Mauvais-Jarvis, 2012). The oestrogen inhibition effect of tamoxifen may modulate the interactive role of insulin and oestrogen (Bryzgalova et al, 2006; Lundholm et al, 2008; Rondini et al, 2011). A previous study disclosed that the oestrogen receptor alpha gene increases susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese women (Huang et al, 2006). An animal study also revealed that oestrogen can prevent insulin-deficient diabetes in mice (Le May et al, 2006). Furthermore, tamoxifen use can lead to hypertriglyceridemia and fatty liver disease, both of which are features of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (Elisaf et al, 2000; Sakhri et al, 2010; Lipscombe et al, 2013). In addition, previous studies have indicated that type 1 insulin-like growth factor (IGF) is an independent prognostic marker for oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen, because tamoxifen resistance was primarily mediated by IGF signalling activation (Fagan et al, 2012; Winder et al, 2014), and tamoxifen treatment has been demonstrated to reduce IGF levels (Ho et al, 1998); conversely, low levels of IGF binding protein-1 have been suggested to predict the long-term development of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged populations (Lewitt et al, 2008; Petersson et al, 2009).

Chemotherapy might also play a role in the initiation of diabetes among breast cancer patients, and Lipscombe et al (2013) observed that women who received adjuvant chemotherapy experienced a higher rate of diabetes within the first 2 years of breast cancer diagnosis compared with age-matched control subjects without cancer. To eliminate the possible confounding effect of chemotherapy, we adjusted for chemotherapy as well as other treatments in the analyses.

A strength of this study was the use of a population-based nationwide database; however, there were several limitations that warrant mention. First, selection bias might have existed based on the assumption that patients diagnosed with breast cancer or treated with tamoxifen tend to be monitored more closely with more opportunities for diabetes screening. However, this concern can be diminished because the risk of diabetes among breast cancer patients increased gradually over time whereas the influence of enhanced health care might be expected to be greater in the period after cancer diagnosis (Lipscombe et al, 2013). Second, a survival bias cannot be completely excluded as women taking tamoxifen usually have a better prognosis and are more likely to survive long enough to develop diabetes. Third, information regarding the life style or behaviour of subjects is unavailable in the NHIRD, rendering it impossible to adjust for health-related behavioural factors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, which can increase the risk of breast cancer (Gao et al, 2013). Conversely, smoking is thought to be an independent risk factor for diabetes and light-to-moderate alcohol consumption was suggested to be associated with a reduced risk of diabetes (Hu, 2011). Fourth, obesity is a well-known risk factor for both breast cancer and diabetes (Kim et al, 2012; Ligibel and Strickler, 2013). In addition, breast cancer survivors have been shown to gain weight, and as many as 50–96% of women experience significant weight gain during treatment (Rock and Demark-Wahnefried, 2002), which is associated with adverse health consequences, including diabetes (Vance et al, 2011). The NHIRD, however, does not provide body weight or body mass index information, and we were unable to conduct sophisticated tests by adjusting for these variables. Fifth, the NHIRD lacks oestrogen receptor status, so we cannot provide more compelling evidence by testing tamoxifen as a risk factor for diabetes among age-adjusted oestrogen-receptor-positive cancer patients. Sixth, the family history of diabetes and the history of gestational diabetes are also unavailable in the NHIRD, so we cannot adjust their impact on the relationship between breast cancer and diabetes. Finally, menopause information is not recorded in the NHIRD; therefore, we could not precisely determine any distinct effects of tamoxifen on diabetes between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. We used 55 years as a cut-off age for analyses. Despite the limitations of the administrative data, the information regarding the use of tamoxifen in breast cancer patients and diabetes diagnoses were highly reliable.

In summary, women diagnosed with breast cancer exhibited a higher risk of subsequent diabetes development and tamoxifen might partially account for this increased risk. In addition to the possible common risk factors shared by breast cancer and diabetes, tamoxifen might link to diabetes through some plausible mechanisms. Although this potential side effect raises concerns, the benefits of tamoxifen in treating breast cancer are well established and far outweigh the potential risks. Additional large population-based case–control studies are required to verify our findings before any confirmatory conclusion can be made.

Change history

28 October 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Amir E, Seruga B, Niraula S, Carlsson L, Ocaña A (2011) Toxicity of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 1299–1309.

Bordeleau L, Lipscombe L, Lubinski J, Ghadirian P, Foulkes WD, Neuhausen S, Ainsworth P, Pollak M, Sun P, Narod SA Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group (2011) Diabetes and breast cancer among women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer 117: 1812–1818.

Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Ahren B, Zierath JR, Galuska D, Steiler TL, Dahlman-Wright K, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA, Efendic S, Khan A (2006) Evidence that oestrogen receptor-alpha plays an important role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice: insulin sensitivity in the liver. Diabetologia 49: 588–597.

Cancer Statistics Annual Report (2014) Taiwan Cancer Registry. [Online]. Available at http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/main.php?Page=N2 . Accessed 27 August 2014.

Cleveland RJ, North KE, Stevens J, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Gammon MD (2012) The association of diabetes with breast cancer incidence and mortality in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project. Cancer Causes Control 23: 1193–1203.

Department of Health, Taiwan (2012) Mortality statistics of Taiwan in 2012. Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan. [Online]. Available at http://health99.hpa.gov.tw/Hot_News/h_NewsDetailN.aspx?TopIcNo=6798 . Accessed 11 April 2014.

Elisaf MS, Nakou K, Liamis G, Pavlidis NA (2000) Tamoxifen-induced severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis. Ann Oncol 11: 1067–1069.

Fagan DH, Uselman RR, Sachdev D, Yee D (2012) Acquired resistance to tamoxifen is associated with loss of the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor: implications for breast cancer treatment. Cancer Res 72: 3372–3380.

Gao CM, Ding JH, Li SP, Liu YT, Qian Y, Chang J, Tang JH, Tajima K (2013) Active and passive smoking, and alcohol drinking and breast cancer risk in Chinese women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14: 993–996.

Godsland IF (2005) Oestrogens and insulin secretion. Diabetologia 48: 2213–2220.

Goldhirsch A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ (2005) Meeting highlights: international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2005. Ann Oncol 16: 1569–1583.

Hardefeldt PJ, Edirimanne S, Eslick GD (2012) Diabetes increases the risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer 19: 793–803.

Ho GH, Ji CY, Phang BH, Lee KO, Soo KC, Ng EH (1998) Tamoxifen alters levels of serum insulin-like growth factors and binding proteins in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective paired cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 5: 361–367.

Hu FB (2011) Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care 34: 1249–1257.

Huang Q, Wang TH, Lu WS, Mu PW, Yang YF, Liang WW, Li CX, Lin GP (2006) Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphism associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the serum lipid concentration in Chinese women in Guangzhou. Chin Med J (Engl) 119: 1794–1801.

Kim CH, Kim HK, Bae SJ, Kim EH, Park JY (2012) Independent impact of body mass index and metabolic syndrome on the risk of type 2 diabetes in Koreans. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 10: 321–325.

La Vecchia C, Giordano SH, Hortobagyi GN, Chabner B (2011) Overweight, obesity, diabetes, and risk of breast cancer: interlocking pieces of the puzzle. Oncologist 16: 726–729.

Larsson SC, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A (2007) Diabetes mellitus and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 121: 856–862.

Le May C, Chu K, Hu M, Ortega CS, Simpson ER, Korach KS, Tsai MJ, Mauvais-Jarvis F (2006) Estrogens protect pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis and prevent insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9232–9237.

Lewitt MS, Hilding A, Ostenson CG, Efendic S, Brismar K, Hall K (2008) Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 in the prediction and development of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Swedish men. Diabetologia 51: 1135–1145.

Ligibel JA, Strickler HD (2013) Obesity and its impact on breast cancer: tumor incidence, recurrence, survival, and possible interventions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book pp 52–59.

Lipscombe LL, Fischer HD, Yun L, Gruneir A, Austin P, Paszat L, Anderson GM, Rochon PA (2012) Association between tamoxifen treatment and diabetes: a population-based study. Cancer 118: 2615–2622.

Lipscombe LL, Goodwin PJ, Zinman B, McLaughlin JR, Hux JE (2006) Increased prevalence of prior breast cancer in women with newly diagnosed diabetes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 98: 303–309.

Lipscombe LL, Chan WW, Yun L, Austin PC, Anderson GM, Rochon PA (2013) Incidence of diabetes among postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. Diabetologia 56: 476–483.

Liu S, Mauvais-Jarvis F (2009) Rapid, nongenomic estrogen actions protect pancreatic islet survival. Islets 1: 273–275.

Lundholm L, Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Portwood N, Fält S, Berndt KD, Dicker A, Galuska D, Zierath JR, Gustafsson JA, Efendic S, Dahlman-Wright K, Khan A (2008) The estrogen receptor {alpha}-selective agonist propyl pyrazole triol improves glucose tolerance in ob/ob mice; potential molecular mechanisms. J Endocrinol 199: 275–286.

MacGregor JI, Jordan VC (1998) Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev 50: 151–196.

McCarthy NJ (2004) Care of the breast cancer survivor: increased survival rates present a new set of challenges. Postgrad Med 116: 39–40, 42, 45-46.

Osborne CK (1998) Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 339: 1609–1618.

Petersson U, Ostgren CJ, Brudin L, Brismar K, Nilsson PM (2009) Low levels of insulin-like growth-factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) are prospectively associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT): the Söderåkra Cardiovascular Risk Factor Study. Diabetes Metab 35: 198–205.

Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Green AR, Paish EC, Powe DG, Gee J, Nicholson RI, Lee AH, Robertson JF, Ellis IO (2007) Biologic and clinical characteristics of breast cancer with single hormone receptor positive phenotype. J Clin Oncol 25: 4772–4778.

Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W (2002) Nutrition and survival after the diagnosis of breast cancer: a review of the evidence. J Clin Oncol 20: 3302–3316.

Rondini EA, Harvey AE, Steibel JP, Hursting SD, Fenton JI (2011) Energy balance modulates colon tumor growth: interactive roles of insulin and estrogen. Mol Carcinog 50: 370–382.

Sakhri J, Ben Salem C, Harbi H, Fathallah N, Ltaief R (2010) Severe acute pancreatitis due to tamoxifen-induced hypertriglyceridemia with positive rechallenge. JOP 11: 382–384.

Tiano JP, Mauvais-Jarvis F (2012) Importance of oestrogen receptors to preserve functional β-cell mass in diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8: 342–351.

Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R (2011) Weight gain in breast cancer survivor: prevalence, pattern, and health consequence. Obes Rev 12: 282–294.

Wigertz A, Ahlgren J, Holmqvist M, Fornander T, Adolfsson J, Lindman H, Lindman H, Bergkvist L, Lambe M (2012) Adherence and discontinuation of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer patients: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133: 367–373.

Winder T, Giamas G, Wilson PM, Zhang W, Yang D, Bohanes P, Ning Y, Gerger A, Stebbing J, Lenz HJ (2014) Insulin-like growth factor receptor polymorphism defines clinical outcome in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Pharmacogenomics J 14: 28–34.

Yang LH, Tseng HS, Lin C, Chen LS, Chen ST, Kuo SJ, Chen DR (2012) Survival benefit of tamoxifen in estrogen receptor-negative and progesterone receptor-positive low grade breast cancer patients. J Breast Cancer 15: 288–295.

Yeh WL, Lin HY, Wu HM, Chen DR (2014) Combination treatment of tamoxifen with risperidone in breast cancer. PLoS One 9: e98805.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the study projects in China Medical University (CMU102-BC-2); Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW103-TDU-B-212-113002); Health and Welfare Surcharge of Tobacco Products; China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence (MOHW103-TD-B-111-03, Taiwan); and International Research-Intensive Centers of Excellence in Taiwan (I-RiCE; NSC101-2911-I-002-303). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding received for this study.

Author contributions

L-MS, J-AL, and C-HK contributed to conception and design. Administrative support was provided by H-JC and C-HK. L-MS and C-HK participated in collection and assembly of data. L-MS, H-JC, and C-HK contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors wrote the manuscript and gave final approval.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, LM., Chen, HJ., Liang, JA. et al. Association of tamoxifen use and increased diabetes among Asian women diagnosed with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 111, 1836–1842 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.488

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.488

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Diabetes mellitus in breast cancer survivors: metabolic effects of endocrine therapy

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2024)

-

Development of cardiometabolic risk factors following endocrine therapy in women with breast cancer

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2023)

-

Breast cancer and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2023)