Abstract

Background:

Evidence for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) preventing head and neck cancer (HNC) is inconclusive; however, there is some suggestion that aspirin may exert a protective effect.

Methods:

Using data from the United States National Cancer Institute Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, we examined the association between aspirin and ibuprofen use and HNC.

Results:

Regular aspirin use was associated with a significant 22% reduction in HNC risk. No association was observed with regular ibuprofen use.

Conclusion:

Aspirin may have potential as a chemopreventive agent for HNC, but further investigation is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Over 600 000 cases of head and neck cancer (HNC) occur annually (Freedman et al, 2007). Primary risk factors include tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption (WHO, 2009). Head and neck cancer is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality (Jayaprakask et al, 2006).

Several studies have shown non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce cancer risk (Rothwell et al, 2010, Bosetti et al, 2012). A systematic review by our group investigated the association between NSAID use and HNC (Wilson et al, 2011). Five studies met the inclusion criteria but each had significant limitations, including small sample size, lack of information on over-the-counter NSAID use and important confounding factors (Bosetti et al, 2003; Friis et al, 2003, 2006). Two studies indicated a protective effect of aspirin on HNC risk (Bosetti et al, 2003; Jayaprakash et al, 2006).

An upregulation of the expression of the inducible, inflammatory cyclo-oxygenase enzyme (COX-2) has been observed in many cancers, including HNC, and premalignant head and neck lesions (Mohan and Epstein, 2003; Altorki et al, 2004). It is thought NSAIDs may prevent cancer development by inhibiting COX-2 and the downstream biological pathways implicated in carcinogenesis (Liao et al, 2007); other COX-2 independent pathways have also been suggested (Hwang et al, 2002: Kashfi, Ragas, 2005).

Using data from the National Cancer Institute Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) randomised controlled screening trial a large scale prospective investigation of the effect of aspirin and ibuprofen on HNC risk was undertaken.

Materials and methods

The PLCO trial design is described in detail elsewhere (Prorok et al, 2000). Between November 1993 and September 2001, almost 155 000 participants aged 55–74 years were recruited from ten US screening centres and randomly assigned to an intervention arm (screened for colorectal, lung, and ovarian or prostate cancer) or usual care arm. Over 99% of participants were followed up annually for cancer diagnosis and death. Cancer confirmation was ascertained from diagnostic information.

This investigation includes cases from both arms of the PLCO trial with no previous cancer history who completed the baseline questionnaire and provided information on aspirin and ibuprofen use. Participants were followed from enrolment to 31 December 2006.

Cases were defined as individuals diagnosed with a primary HNC at least 1 year after completion of the baseline questionnaire. Head and neck cancer sites comprised International Classification of Disease for Oncology version-2 topography codes C00.0-C14.8 and C30.0–C32.9. Lip cancers were excluded as the primary aetiology (exposure to UV light) was considered dissimilar to that of other included cancer sites.

Information on demographic characteristics, medical history, aspirin or ibuprofen use, anthropometric measures, and lifestyle was collected at baseline using a comprehensive self-completed questionnaire. Aspirin and ibuprofen use elicited a yes/no response to the following questions: during the last 12 months have you regularly used ‘aspirin or aspirin-containing products such as Bayer, Bufferin, or Anacin’, or ‘ibuprofen containing products such as Advil, Nuprin or Motrin’. Regular use was not defined. Self-reported frequency of use was measured by the number of tablets usually taken: 1 per day, ⩾2 per day; 1 per week, 2 per week, 3–4 per week;<2 per month, 2–3 per month, this was further categorised into daily and weekly/monthly use. Further information on frequency of use and dose usually taken (aspirin use only), was available in a supplementary questionnaire (SQX) completed between 2006 and 2007. Current body mass index (BMI) was calculated and categorised according to the World Health Organisation classification. Current smoking status was defined as never or ever use. Maximum cigarette pack years were calculated and categorised into quartiles. Self-reported alcohol consumption in the 12 months preceding interview was obtained at baseline for individuals in the screening arm.

Analysis

Using Cox proportional hazard modelling unadjusted and multi-variable adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for HNC risk were estimated. Participants were censored at the earliest of HNC diagnosis, death or 31 December 2006. Biologically plausible confounding variables were initially included in the model and excluded if P-values were >0.10. The possibility of aspirin users also using ibuprofen, and vice versa, was included as a possible confounder in the respective models. Body mass index values <12 and >60 kg m−2 were excluded from the model as possible outliers using listwise deletion.

A subanalysis using participants with information on alcohol use was conducted. Adjusted hazard ratios were calculated with, and without, alcohol as a covariate to establish if alcohol use altered the risk estimate. Tests for interactions between aspirin/ibuprofen use and smoking status and alcohol use were conducted. The effect of aspirin use on HNC risk was assessed by increasing alcohol use within those individuals in the screening arm who had information on alcohol use. Using available histological data a restricted analysis was conducted using only squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) HNCs.

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA, version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Tests of statistical significance were two-sided. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

After initial exclusions, 142 034 individuals remained eligible for analysis. The mean follow-up time was ∼9 years (range 0–13.1 years), with a total person years of follow-up of 1 276 115 years. During follow-up, 316 individuals had a confirmed HNC. Cohort characteristics are shown in Table 1.

At baseline, 49.2% and 29.6% of participants reported regular aspirin and ibuprofen use, respectively. The later SQX provided an indication of aspirin strength; most non-HNC cases reporting daily usage in both questionnaires were taking low dose (81 mg) aspirin. Those reporting weekly/monthly use in the SQX tended to take higher doses (325 mg). A shift to increased frequency of use, particularly by those reporting weekly/monthly uses was also observed.

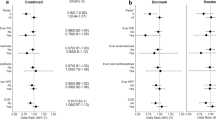

Unadjusted and multi-variable adjusted HRs for aspirin and ibuprofen use and HNC risk are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for possible confounders, a decreased risk of HNC was observed with regular aspirin use (AHR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98). A significant reduction of HNC risk was observed between weekly and monthly aspirin use; daily aspirin use was not significantly associated with a reduced HNC risk, Table 2. No association was observed between ibuprofen use and HNC. When analyses were restricted SCC sites estimates for regular aspirin and ibuprofen use were similar to all HNCs (AHR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56–0.93; AHR 0.96, 95% CI 0.71–1.29, respectively).

The subtype specific analyses showed a significant protective association between aspirin use and laryngeal cancer (AHR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45–0.99). An inverse, but non-significant, association between aspirin use and cancers of the oropharynx, and ‘other sites combined’ was observed (Supplementary Data, Table 1).

Including alcohol use as a possible confounder, the AHRs did not alter for aspirin or ibuprofen use. A significant interaction (P=0.004) between alcohol and aspirin was observed. Stratification by increasing alcohol use revealed an increasing reduction in HNC risk in aspirin users compared with non-users. No protective association was observed in non-alcohol users (Table 3). No interaction between aspirin/ibuprofen use and tobacco use was evident.

Discussion

Consistent with other studies (Bosetti et al, 2003; Jayaprakash et al, 2006; Ahmadi et al, 2010), we report a significant reduction in HNC risk with aspirin use, with the strongest protective effect for laryngeal cancers. No association was observed between HNC and ibuprofen use.

No association with ibuprofen use was observed. Compared with aspirin use, ibuprofen use was more infrequent and taken by proportionately fewer individuals; the reduction in power may, therefore, explain the lack of association. In addition, our analysis revealed a slight, non-significant, reduction in HNC risk with increased frequency of ibuprofen use, suggesting a possible causal effect. Alternatively, aspirin may exert different COX-2 independent effects on reducing cancer compared with ibuprofen (Elwood et al, 2009). A greater reduction in HNC risk was observed with weekly/monthly aspirin use than daily use. The later SQX indicated an increase in dosage and frequency of use among weekly/monthly aspirin users, which may explain the absence of a protective trend with increased frequency of use.

There was a near negligible difference between risk estimates with alcohol included in the model. Cohort alcohol intake was relatively low, possibly explaining the lack of effect on the HRs. Interaction analyses suggested that alcohol may be modifying the effect of aspirin use on HNC risk. A subanalysis in individuals with information on alcohol use revealed an increasing reduction in HNC risk, albeit non-significant, with aspirin use among participants with increasing alcohol use. The exact mechanism by which this may be occurring is uncertain. Ethanol found in alcohol has been reported to act as a local irritant (Llewellyn et al, 2001) potentially leading to localised inflammation, which may possibly explain the observed reduction in HNC in aspirin users who consume alcohol. Previous studies have not reported alcohol as a possible effect modifier, further investigation is merited.

The site-specific analysis observed a significant protective effect with aspirin use and laryngeal cancer. The AHR was reduced for cancers of the oropharynx; however, the association was not significant (AHR 0.70 95% CI 0.41–1.19), possibly due to the small numbers involved. Jayaprakash et al (2006) observed a similar reduction in oropharyngeal cancer risk with aspirin use. The majority of oropharyngeal sites have been described as human papillomavirus (HPV)-related (Ramqvist and Dalianis, 2010). There is some evidence to suggest an upregulation of COX-2 in HPV-infected tissues (Subbaramiah and Dannenberg, 2007).

Strengths of this study include the ability to control for important confounders, specifically tobacco use. Follow-up time was fairly long; follow-up exceeded 99%. The study was limited by the lack of complete information on alcohol use, with information only available in the screening arm. However, there was little difference between participant characteristics within the two study arms and adjustment for alcohol had no effect on the point estimates. Dosage was from a later questionnaire and could only provide an indication of possible dosage.

This study supports the view that aspirin may have potential as a chemopreventive agent for HNC. There was little evidence to suggest that ibuprofen use was associated with reduced HNC risk. Further studies are required, in particular, those examining the strength and duration of aspirin use that may be required to exert a protective effect.

Change history

19 March 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ahmadi N, Goldman R, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch F, Noone A, Kosti O, Davidson BJ (2010) Decreased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. (published online). Int J Otolaryngol doi:10.1155/2010/424161

Altorki HK, Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ (2004) COX-2 Inhibition in upper aerodigestive tract tumors. Semin Onco 31: 30–35

Bosetti C, Rosato V, Gallus S, Cuzick J, La Vecchia C (2012) Aspirin and cancer risk: a quantitative review to 2011. Ann Oncol 23: 1403–1415

Bosetti C, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Negri E, Garavello W, La Vecchia C (2003) Aspirin use and cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Br J Cancer 88: 672–674

Elwood PC, Gallagher AM, Duthie GG, Mur LA, Morgan G (2009) Aspirin, salicylates, and cancer. Lancet 373: 1301–1309

Freedman ND, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Abnet CC (2007) Alcohol and head and neck cancer risk in a prospective study. Br J Cancer 96: 1469–1474

Friis S, Poulsen A, Pedersen L, Baron JA, Sorensen HT (2006) Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of oral cancer: a cohort study. Br J Cancer 95: 363–365

Friis S, Sørensen HT, McLaughlin JK, Johnsen SP, Blot WJ, Olsen JH (2003) A population-based cohort study of the risk of colorectal and other cancers among users of low-dose aspirin. Br J Cancer 88: 684–688

Hunter KD, Parkinson K, Harrison PR (2005) Profiling early head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 127–135

Hwang DH, Fung V, Dannenberg AJ (2002) National Cancer Institute workshop on chemopreventive properties of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: role of cox-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Neoplasia 4: 91–97

Jayaprakash V, Rigual NR, Moysich KB, Loree TR, Nasca MA, Menezes RJ, Reid ME (2006) Chemoprevention of head and neck cancer with aspirin: a case-control study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 132: 1231–1236

Kashfi K, Ragas B (2005) Cancer prevention: a new era beyond cyclooxygenase-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314: 1–8

Liao Z, Mason KA, Milas L (2007) Cyclo-oxygenase-2 and its inhibition in cancer. Is there a role? Drugs 67: 821–845

Llewellyn CD, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya KAAS (2001) Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity in young people – a complete literature review. Oral Oncol 37: 401–418

Mohan S, Epstein JB (2003) Carcinogenesis and cyclooxygenase: the potential role of COX-2 inhibition in upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol 39: 537–546

Pereg D, Lishner M (2005) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention and treatment of cancer. J. Intern Med 258: 115–123

Prorok PC, Andriole GL, Bresalier RS, Buys SS, Chia D, Crawford ED, Fogel R, Gelmann EP, Gilbert F, Hasson MA, Hayes RB, Johnson CC, Mandel JS, Oberman A, O'Brien B, Oken MM, Rafla S, Reding D, Rutt W, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi L, Gohagan JK Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial Project Team (2000) Design of the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial. Control Clin Trials 21: 273S–309S

Ramqvist T, Dalianis T (2010) Oropharyngeal cancer epidemic and human papillomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1671–1677

Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, Meade TW (2010) Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of fi ve randomised trials. Lancet 376: 1741–1750

Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ (2007) Cyclooxygenase-2 transcription is regulated by human papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins: evidence of a corepressor/coactivator exchange. Cancer Res 67: 3976–3985

Wang Z (2005) The role of COX-2 in oral cancer development, and chemoprevention/ treatment of oral cancer by selective COX-2 inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des 11: 1771–1777

Wilson JC, Anderson LA, Murray LJ, Hughes CM (2011) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and aspirin use and the risk of head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control 22: 803–810

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by contracts from the Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute; NIH, DHHS. We thank Drs Christine Berg and Philip Prorok, Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, the Screening Centre investigators and staff of the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial; Mr Tom Riley and staff, Information Management Services, Inc.; Ms Barbara O’Brien and staff, Westat, Inc. Most importantly, we acknowledge the study participants for their contributions to making this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, J., Murray, L., Hughes, C. et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and aspirin use and the risk of head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer 108, 1178–1181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.73

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.73

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Aspirin sensitivity of PIK3CA-mutated Colorectal Cancer: potential mechanisms revisited

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2022)

-

Low-dose aspirin confers a survival benefit in patients with pathological advanced-stage oral squamous cell carcinoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Associations between aspirin use and the risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of observational studies

BMC Cancer (2018)

-

Aspirin and the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases: An Approach Based on Individualized, Integrated Estimation of Risk

High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention (2017)