Abstract

Background:

Nuclear factor κB (NFκB) has a critical role in the pathophysiology of multiple myeloma. Targeting NFκB is an important strategy for anti-myeloma drug discovery.

Methods:

Luciferase assay was used to evaluate the effects of DETT on NFκB activity. Annexin V–PI double staining and immunoblotting were used to evaluate DETT-induced cell apoptosis and suppression of NFκB signalling. Anti-myeloma activity was studied in nude mice.

Results:

DETT downregulated IKKα, β, p65, and p50 expression and inhibited phosphorylation of p65 (Ser536) and IκBα. Simultaneously, DETT increased IκBα, an inhibitor of the p65/p50 heterodimer, even in the presence of stimulants lipopolysaccharide, tumour necrosis factor-α, or interleukin-6. DETT inhibited NFκB transcription activity and downregulated NFκB-targeted genes, including Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and XIAP as measured by their protein expression. Deregulation of NFκB signalling by DETT resulted in MM cell apoptosis characterised by cleavage of caspase-3, caspase-8, and PARP. Notably, this apoptosis was partly blocked by the activation of NFκB signalling in the presence of TNFα and IL-6. Moreover, DETT delayed myeloma tumour growth in nude mice without overt toxicity.

Conclusion:

DETT displays a promising potential for MM therapy as an inhibitor of the NFκB signalling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy derived from plasma cells and is characterised by malignant monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, multiple bone lesions, and hypercalcemia. It accounts for 2% of all cancers and leads the second place in hematological malignancies (Raab et al, 2009). In the past decade, several novel drugs have been marketed for MM therapy, including proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and carfilzomib, and immunomodulators thalidomide and its analogs. However, MM remains incurable because of its complicated pathophysiology. Novel anti-MM drugs are in high demand.

Nuclear factor κB (NFκB) is a nuclear transcription factor that regulates the expression of a number of genes critical for cell proliferation, viral replication, tumourigenesis, inflammation, and various autoimmune diseases (Aggarwal et al, 2006). In mammals, the NFκB family is comprised of five different members: c-Rel, p65 (Rel A), Rel B, p50/p105 (NFκB1), and p52/p100 (NFκB2). The heterodimer p50/p65 is the most common complex in many cell types (May and Ghosh, 1998; Barkett and Gilmore, 1999). In non-stimulated cells, inactive NFκB complexes are bound with a class of inhibitor proteins called IκB, including IκBα, IκBβ, IκBγ, and the product of the putative proto-oncogene bcl-3 (Whiteside et al, 1997; May and Ghosh, 1998). When IκB is phosphorylated and subsequently degraded by the proteasome, NFκB is released from IκB and is translocated to the nucleus where it modulates gene expression (Barkett and Gilmore, 1999). Nuclear translocation of NFκB can be induced by a variety of stimuli, including tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and interleukins (Bitzer et al, 2000).

Recent evidence indicates that NFκB and its signalling pathways are constitutively activated in both myeloma cell lines and primary myeloma cells (Annunziata et al, 2007; Demchenko and Kuehl, 2010). Inhibition of NFκB signals by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induces MM cell apoptosis, suggesting that NFκB is a potential target for anti-MM drug discovery. In the present study, we found that one of the tetrahydro-2H-1,3,5-thiadiazine-2-thione derivatives displayed potent anti-myeloma activity by inhibiting the NFκB signalling pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and chemicals

Human MM cell lines KMS11, LP1, OCI-My5, OPM2, RPMI-8226, and U266 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and were grown in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium as described previously (Mao et al, 2007). DETT or 3,5-diethyl-1,3,5-thiadiazinane-2-thione (Figure 2A) was purchased from Maybridge, Tintagel, UK.

Determination of apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, San Jose, CA, USA) with Annexin V–FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) as described previously (Ling et al, 2012).

Cell lysates preparation

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in an ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM EGTA, 12 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 10 mM NaF, 16 mg ml−1 benzamidine hydrochloride, and cocktail protease inhibitors (10 mg ml−1 phenanthroline, 10 mg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 mg ml−1 leupeptin, 10 mg ml−1 pepstatin, and 1 nM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride; Mao et al, 2011). Cell lysates were then clarified at high speed at 4 °C.

To isolate cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared using the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit (Beyotime, Nantong, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA protocol (Beyotime).

Western blotting

Forty micrograms of total proteins were subject to fractionation on a SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and followed by immunoblotting assay as described previously (Li et al, 2013). Primary antibodies, including PARP, CCND2, Bcl-2, XIAP, Bim, caspase-3, caspase-8, NFκB, IκBα, phospho-IκBα, p105, p50, p65, phospho-p65, IKKα, IKKβ, and Histone H3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The GAPDH antibody was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Beyotime. Signal detection was performed by the Enhanced Chemical Luminescence method (Beyotime) or by the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transient transfection, luciferase, and β-galactosidase assays

HEK293T cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes (Nest Biotechnology Co., Wuxi, China). When cells were 60% confluent, the medium was replaced with serum-free Opti-MEM (Gibco BRL, Shanghai, China). Cells were cotransfected with the pNFκB-Luciferase reporter plasmid (pNFκB-Luc, Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) and the pGL4-β-galactosidase vector (Promega, Beijing, China) using 25KD PEI (Sigma) as the gene carrier. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were trypsinised, and equal numbers of cells were plated in 24-well plates for 12 h. Cells were then treated with 0, 15, or 30 μ M of DETT for 9 h, followed by stimulation with or without LPS (5 μg ml−1) for 3 h. Luciferase assays and β-gal enzyme assays were performed 12 h after addition of DETT according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalised to β-gal expression for each sample (Mao et al, 2007). All transfection experiments were performed in duplicate.

Multiple myeloma xenograft model

Female BALB/c nude mice (5–6 weeks old) were obtained from Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd, Shangai, China (Zhang et al, 2013). All animal studies were conducted according to the protocols approved by the Ethical Committee of Experimental Animals of Soochow University. All mice were subcutaneously inoculated with RPMI-8226 cells (3 × 107 cells per injection) in the right flank in 200 μl of sterile PBS containing 100 μl of Matrigel (BD Pharmingen). When tumours were measurable, mice were randomly assigned into two groups, one group was orally administrated DETT (50 mg kg−1day−1, 1/12 LD50) and the other received vehicle. Tumour sizes and mice body weights were monitored every other day as described previously (Mao et al, 2011). Mice were killed 20 days after treatment with DETT, and all tumours were excised. After weighing and size measurement, tumour samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C for further study. To examine the NFκB signals in tumour tissues after DETT treatment, tumour tissues were subject to western blotting assay against p65, p50, and PARP as described previously (Mao et al, 2008).

Statistical analysis

When it was applicable, statistical significance was analyzed by using the Student’s t-test.

Results

DETT inhibits the NFκB signalling pathway in MM cells

NFκB is critical for MM cell proliferation and survival (Annunziata et al, 2007; Demchenko and Kuehl, 2010), but there was little evidence to visualise NFκB expression in MM cells, therefore we first evaluated NFκB components in a panel of MM cells. Immunoblotting analysis on six MM cell lines revealed that both p105 and p65 were universally highly expressed in all the cell lines. IKKα, β, p50, IκBα, and phosphorylated p65 were highly expressed in four of the six cell lines examined (Figure 1), suggesting that NFκB were important for MM cell proliferation and survival.

Constitutive expression of the NF κ B signalling components in MM cells. MM cell lines LP1, RPMI-8226 (8226), OCI-My5 (My5), U266, OPM2, and KMS11 were prepared for the whole-cell lysates in the RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% SDS. Immunoblotting analyses were performed against specific antibodies as indicated.

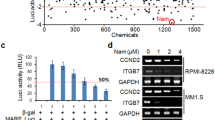

Because NFκB is a ubiquitous transcription factor, we next designed a NFκB responsive element–driven luciferase reporter to evaluate DETT activity. A luciferase reporter specifically responsive to NFκB was transfected into HEK293T cells followed by DETT treatment in the presence or absence of 5 μg ml−1 LPS. As shown in Figure 2B, DETT suppressed baseline activity of NFκB-driving luciferase. More impressively, it suppressed LPS-induced NFκB activity by 80% compared with the control. To further understand how DETT blocked the NFκB pathway, we measured the changes of protein expression of the NFκB-associated members in MM cell lines OCI-My5 and RPMI-8226 after treatment with increasing concentrations of DETT for 24 h. As shown in Figure 2C, all components, including IKKα, β, p65, phospho-p65, and phospho-IκBα, were downregulated by DETT. In contrast, total IκBα was significantly increased following DETT treatment (Figure 2C).

DETT inhibits NF κ B activity. (A) The structure of the DETT. (B) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with NFκB-luciferase reporter and β-gal expression plasmids. Twenty-four hours later, cells were trypsinised, and equal numbers of cells were plated in 24-well plates and cultured for 12 h. Cells were then treated with 0, 15, or 30 μ M of DETT for 9 h, followed by stimulation with or without LPS (5 μg ml−1) for 3 h. Then luciferase activity was measured using Bright-Glo reagents (Promega). #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared with the control. (C) RPMI-8226 and OCI-My5 cells were treated with DETT (0, 15, or 30 μM) for 24 h and analyzed by western blotting against specific antibodies as indicated. (D) RPMI-8226 cells were pre-treated with DETT at 0, 15, or 30 μM for 24 h, followed by addition of TNFα (T, 50 ng ml−1, 20 min) or LPS (L, 5 μg ml−1, 3 h). Whole-cell lysates were then prepared for NFκB analysis against specific antibodies.

Phosphorylation of p65 (Ser536) mediated by IKKs (Sakurai et al, 1999) facilitates p65 nuclear translocation and DNA binding (Zhong et al, 2002). Because both IKKα and β were downregulated by DETT (Figure 2C), we wondered whether DETT could suppress p65 phosphorylation in the presence of NFκB signalling stimulants TNFα and LPS. To determine this, MM cells were treated with DETT for 24 h followed by addition of TNFα (20 min) or LPS (3 h). Immunoblotting assays revealed that both TNFα and LPS induced p65 phosphorylation, but it was completely abolished by DETT (Figure 2D). Notably, consistent with the change of phospho-p65, phospho-IκBα was also decreased, whereas total IκBα was increased by DETT (Figure 2D).

DETT suppressed NFκB activity in a manner different from bortezomib

Bortezomib is a potent anti-MM drug by inhibiting the proteasomes, stabilising IκBα, and suppressing p65/p50 activation. Because DETT was also able to inhibit NFκB signals, we wondered whether these two agents act in a similar manner. To this end, OCI-My5 and RPMI-8226 were treated with DETT or bortezomib followed by analysis of the NFκB signalling. Immunoblotting revealed that DETT and bortezomib exerted similar effects on p65, p50, and phospho-p65. Both agents decreased phospho-p65, p65, and p50 in the cytosol and suppressed p65 phosphorylation in the nuclear fragment, while total p65 and p50 were not affected (Figure 3A). However, their effects on IκBα were different. As shown in Figure 3B, bortezomib stabilised phospho-IκBα, while DETT decreased phospho-IκBα in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3B); accordingly, total IκBα was increased by DETT but not by bortezomib (Figure 3B). This result suggested bortezomib stabilises IκBα protein by inhibiting proteasomes (Murray and Norbury, 2000), while DETT probably inhibits IKKs, thus decreasing phosphorylation of IκBα and preventing it from degradation (Figure 2).

DETT protects I κ B α in a manner different from bortezomib. RPMI-8226 and OCI-My5 cells were treated with DETT (0, 15, or 30 μM) or bortezomib (BZ, 20 nM) for 24 h, and whole-cell lysates were then prepared to isolate the nuclear and cytosolic fragments for western blotting assays against specific antibodies. (A) Expression of p-p65, p65 and p50 in the cytosol and nuclear fragments. (B) Expression of p-IκBα and IκBα in the whole cell lysates.

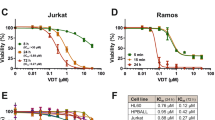

DETT significantly induces MM cell apoptosis

As a ubiquitous transcription factor, NFκB modulates a broad panel of signal transduction involved in cell proliferation, survival, and anti-apoptosis, therefore inhibition of NFκB can lead to MM cell death (Yinjun et al, 2005; Fabre et al, 2012). To check whether DETT was able to induce MM cell apoptosis, six MM cell lines, including KMS11, LP1, OCI-My5, OPM2, RPMI-8226, and U266, were treated with DETT (20 μ M) for 24 h, followed by Annexin V and PI double staining and flow cytometric analyses. As shown in Figure 4, DETT induced >45% apoptosis in LP1, OPM2, and OCI-My5 and >39% death in RPMI-8226. In contrast, there were fewer apoptotic cells in U266 and KMS11. Interestingly, these two cell lines only expressed very faint phospho-p65 (Figure 1), thus these results suggested that DETT induced MM cell apoptosis wherein p65 phosphorylation was probably critical in DETT-mediated cell death.

To confirm apoptosis induced by DETT, we next examined the apoptotic signalling in these cell lines. Western blotting analysis revealed that PARP was markedly cleaved by DETT in LP1, OCI-My5, OPM2, and RPMI-8226 cells but less cleaved in U266 and KMS11 (Figure 5A), which was consistent with the apoptotic analysis by flow cytometry (Figure 4). Therefore, these data further demonstrated that DETT-induced MM cell apoptosis is highly associated with NFκB signalling. To further characterise DETT-induced MM cell apoptosis, we evaluated activation of caspase-3 and -8 in OCI-My5 and RPMI-8226 cells. As shown in Figure 5B, DETT induced cleavage of PARP, caspase-3, and -8 in a concentration-dependent manner. Concomitantly, anti-apoptotic proteins XIAP and Bcl-2 were decreased, while pro-apoptotic Bim was induced by DETT (Figure 5C).

DETT activates cell apoptotic pathway and suppresses expression of anti-apoptotic proteins. (A) Six MM cell lines were treated with 0 or 20 μ M of DETT for 24 h, followed by evaluation of PARP. (B) OCI-My5 and RPMI-8226 cells were treated with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 μ M of DETT for 24 h, and cell lysates were subject to caspase-3, caspase-8, PARP, and GAPDH analysis. (C) OCI-My5 and RPMI-8226 were treated with DETT for 24 h, followed by western blotting assay for pro-apoptotic (Bim) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2 and XIAP) proteins using specific antibodies. Abbreviations: Pro-casp3: pro-caspase 3; cle-casp8: cleaved caspase 8.

Activation of NFκB partly suppresses DETT-induced MM cell apoptosis

The aforementioned studies demonstrated that DETT deregulated NFκB signalling, especially suppressed phosphorylation of both p65 and IκBα, and induced MM cell apoptosis. It seemed that sensitivity of MM cells to DETT was associated with NFκB signalling, especially the status of p65 phosphorylation. To verify this hypothesis, RPMI-8226 cells were treated with DETT alone or in combination with NFκB stimulants TNFα or IL-6 in a series of incubation periods. As shown in Figures 6A and B, p65 phosphorylation was induced by TNFα and IL-6 but was markedly decreased by DETT within 4 h. Without TNFα or IL-6, DETT could markedly inhibit p65 phosphorylation and induced PARP cleavage within 2 h. Addition of IL-6 or TNFα activated p65 phosphorylation, and it partly attenuated DETT-induced MM cell apoptosis along with the suppression of NFκB signals (Figure 6). This finding and above studies therefore further demonstrated that DETT induced MM cell apoptosis, at least partly, by suppressing the NFκB signalling.

DETT delays human MM tumour growth in nude mice models

All the above studies have provided reliable evidence that DETT inhibits NFκB signals and induces MM cell apoptosis. To further investigate the effect of DETT against human MM in vivo, a myeloma xenograft model was established by subcutaneous injection of RPMI-8226 cells in the right flanks of nude mice. When the tumours were palpable (around 50 mm3), mice were orally administrated DETT with the dosage of 1/12 LD50 or 50 mg kg−1 on a daily base for 20 days, and tumour sizes and mice body weights were monitored every other day. The results indicated that DETT significantly inhibited tumour growth on the seventh day of administration (Figure 7A). At the end of the experiment, the tumour weights in the vehicle group and DETT treatment group were 1.55±0.438 and 0.48±0.163 g, respectively. Tumour growth was significantly decreased by DETT with the P value=0.000234 (Figure 7B). There were no adverse effects or aberrant behaviour or gross organ damage in DETT-treated mice, which suggested that DETT was well tolerated (Figure 7C). In western blotting analysis, phospho-p65, p65, and p50 were decreased in tumours from the DETT-treated mice but not in those from untreated mice (Figure 7D). Moreover, PARP was also cleaved in the DETT-treated group, suggesting DETT also induced apoptosis in vivo. Taken together, these results supported that DETT displayed significant anti-MM activity in vivo by inhibiting the NFκB signals.

DETT delays myeloma tumour growth in nude mice models. Three million of RPMI-8226 cells were subcutaneously injected in the right flank of each mouse. When tumours were palpable, mice were randomly distributed into two groups, one was orally given DETT (50 mg kg−1) every day, while the other was received the same volume of vehicle. Mice weight and tumour sizes were monitored every other day. (A) The curves of tumour sizes (*, P=0.000444). (B) Tumour weight was measured at the end of the experiment after tumours were excised. (C) The body weights were not markedly changed by DETT based on a measurement every other day. (D) DETT suppressed the expression of p65, phospho-p65, and p50 and cleaved PARP in the tumour tissues from DETT-treated mice.

Discussion

Recent studies found that thiadiazine derivatives represent a class of potential anti-leishmanial agents, in addition to their antibacterial, antifungal, and antimicrobial activity (Monzote Fidalgo et al, 2004). These compounds showed cytotoxic properties against cervical cancer cell line HeLa and colon adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29 but did not display activity against Hep G2 cells (Perez et al, 2000). This selective cytotoxicity of thiadiazine derivatives for certain cancer cell lines suggests that these agents have a potential for the treatment of some specific cancers. Recently, some such derivatives have been reported to inhibit proliferation of chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 and breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-468 as cell cycle inhibitors (Radwan et al, 2012). But the detailed mechanisms of anti-tumour activity have not been defined. In the current work, we found DETT, one of the thiadiazine derivatives, displays potent activity against MM in both in vitro and in vivo models. At a concentration of 5 μM, DETT markedly activates caspase signals in MM cells. In the presence of MM cell activators such as IL-6, DETT still displays potent efficacy in inducing MM apoptosis. Notably, oral administration of DETT at 50 mg kg−1 suppresses MM tumour growth by >70% within 3 weeks. All these results suggest DETT is potent for the treatment of MM. Mechanistically, anti-MM activity of DETT is associated with the NFκB signalling pathway, especially the phosphorylation status of p65, because those MM cell lines such as U266 and KMS11 with only a faint phospho-p65 level are not sensitive to DETT.

There are two NFκB signalling pathways, one is canonical in which the IκBα/p65/p50 complex is the key player, the other one is non-canonical in which p100/RelB is most important (Tully et al, 2012). The canonical pathway contains several strictly regulated steps, including extracellular stimulation, IKK activation, IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, p65/p50 nuclear translocation, NFκB-DNA binding, and NFκB transactivation (Gilmore and Herscovitch, 2006). The traditional concept in the NFκB signalling is that NFκB is inhibited by association with IκBα. Once phosphorylated by IKK upon signalling triggers such as TNFα or IL-6 stimulation, IκBα is subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasomes, and the p65/p50 heterodimer is then liberated and activated followed by nuclear translocation. IκBα is the key negative regulator of the NFκB activation (May and Ghosh, 1998; Kim et al, 2006). Many NFκB inhibitors such as bortezomib induce cancer cell apoptosis by suppressing IκBα degradation thus suppressing NFκB activation (Murray and Norbury, 2000). Bortezomib is an inhibitor of proteasomes thus stabilising hyper-phosphorylated IκBα and maintaining its inhibitory effects on p65/p50. However, different from bortezomib, DETT decreases IκBα phosphorylation and increases total IκBα level (Figure 3). Although the effects of these two agents on NFκB are distinct in terms of phosphorylated and total IκBα proteins, the final effects are probably the same, because bortezomib stabilises phospho-IκBα from proteasomal degradation, while DETT suppresses IκBα phosphorylation, which prevents IκBα from degradation by proteasomes. In DETT-treated MM cells, this is dramatic, because total IκBα was increased by DETT.

In addition to IκBα phosphorylation, more and more studies demonstrated that p65 is also phosphorylated by stimulants such as TNFα (Sakurai et al, 1999). The subunit p65 of NFκB, also called RelA, is the key component of the functional NFκB that is translocated into nuclei where it binds to DNA and modulates gene transcription (Nolan et al, 1991). Phosphorylation of p65 could occur at Ser276, Ser311, Ser529, and Ser536 (Sakurai et al, 1999; Wang et al, 2000; Zhong et al, 2002; Duran et al, 2003; Vermeulen et al, 2003), but the blockage of p65 phosphorylation at Ser536 rather than at Ser276 or Ser529 abolishes p65 transcription activity (Hu et al, 2004). It is believed that phospho-p65 (Ser536) facilitates p65 nuclear translocation, improves its DNA binding, recruits p300 to the p65 complex, and releases p65 from HDAC1 and HDAC3, thereby regulating downstream gene expression (Buss et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2004). Our study showed that, similar to bortezomib, DETT also suppresses p65 phosphorylation in cytoplasm. Because DETT can downregulate the expression of IKKα and β, as well as p65 and IκBα phosphorylation, IKKα/β are probably the major target of DETT. We noticed that DETT leads to concentration- and time-dependent decrease of p65 phosphorylation in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fragments. However, total p65 protein level is only decreased in the cytoplasm but not changed in the nuclei (Figure 3). Moreover, DETT-induced MM cell apoptosis is dependent on p65 phosphorylation level. U266 and KMS11 cells with less phosphorylated p65 are resistant to DETT compared with the other cell lines expressing phospho-p65 (Figures 1, 4, and 5). These findings suggest that NFκB activation with p65 phosphorylation is required for cancer cell survival and could be a target by some chemicals, such as DETT.

The IKKs are key kinases that phosphorylate both p65 and IκBα (Yang et al, 2003; Viatour et al, 2005). Several studies indicate that PI3K/Akt-dependent signalling activates NFκB activity but depends on the relative levels of the IKKα subunit (Gustin et al, 2004). By reviewing the effects of DETT on NFκB signalling nodes, we can conclude that DETT might suppress NFκB activation by inhibiting p65 and IκBα phosphorylation.

Therefore, in the present study, we found that anti-leishmanial thiadiazine-derivative DETT could be a potential anti-myeloma agent by targeting the NFκB signalling. The low toxicity and high potency in MM cell apoptosis and delaying MM tumour growth in vivo merits DETT for further evaluation.

Change history

07 January 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aggarwal BB, Sethi G, Nair A, Ichikawa H (2006) Nuclear factor-kappaB: a holy grail in cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Signal Trans Ther 1: 25–252.

Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W, Dave S, Hurt EM, Tan B, Zhao H, Stephens O, Santra M, Williams DR, Dang L, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy JD Jr, Kuehl WM, Staudt LM (2007) Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell 12: 115–130.

Barkett M, Gilmore TD (1999) Control of apoptosis by Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene 18: 6910–6924.

Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Liang D, Dominguez-Rosales A, Beg AA, Rojkind M, Bottinger EP (2000) A mechanism of suppression of TGF-beta/Smad signaling by NF-kappa B/Rela. Genes Dev 14: 187–197.

Buss H, Dorrie A, Schmitz ML, Hoffmann E, Resch K, Kracht M (2004) Constitutive and interleukin-1-inducible phosphorylation of P65 NF-{kappa}B at Serine 536 is mediated by multiple protein kinases including I{kappa}B kinase (Ikk)-{alpha}, Ikk{beta}, Ikk{epsilon}, Traf family member-associated (Tank)-binding kinase 1 (Tbk1), and an unknown kinase and couples P65 to tata-binding protein-associated factor Ii31-mediated interleukin-8 transcription. J Biol Chem 279: 55633–55643.

Demchenko YN, Kuehl WM (2010) A critical role for the NFkB pathway in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 1: 59–68.

Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2003) Essential role of Rela Ser311 phosphorylation by Zetapkc in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. EMBO J 22: 3910–3918.

Fabre C, Mimura N, Bobb K, Kong SY, Gorgun G, Cirstea D, Hu Y, Minami J, Ohguchi H, Zhang J, Meshulam J, Carrasco RD, Tai YT, Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC (2012) Dual inhibition of canonical and noncanonical NF-kappaB pathways demonstrates significant antitumor activities in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 18: 4669–4681.

Gilmore TD, Herscovitch M (2006) Inhibitors of NF-kappaB signaling: 785 and counting. Oncogene 25: 6887–6899.

Gustin JA, Ozes ON, Akca H, Pincheira R, Mayo LD, Li Q, Guzman JR, Korgaonkar CK, Donner DB (2004) Cell type-specific expression of the ikappab kinases determines the significance of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling to NF-kappa B activation. J Biol Chem 279: 1615–1620.

Hu J, Nakano H, Sakurai H, Colburn NH (2004) Insufficient P65 phosphorylation at S536 specifically contributes to the lack of NF-kappaB activation and transformation in resistant Jb6 cells. Carcinogenesis 25: 1991–2003.

Kim HJ, Hawke N, Baldwin AS (2006) NF-kappaB and Ikk as therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Differ 13: 738–747.

Li J, Cao B, Zhou S, Zhu J, Zhang Z, Hou T, Mao X (2013) Cyproheptadine-induced myeloma cell apoptosis is associated with inhibition of the Pi3k/Akt signaling. Eur J Haematol e-pub ahead of print 23 August 2013 doi:10.1111/ejh.12193.

Ling C, Chen G, Chen G, Zhang Z, Cao B, Han K, Yin J, Chu A, Zhao Y, Mao X (2012) A deuterated analog of dasatinib disrupts cell cycle progression and displays anti-non-small cell lung cancer activity in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer 131: 2411–2419.

Mao X, Cao B, Wood TE, Hurren R, Tong J, Wang X, Wang W, Li J, Jin Y, Sun W, Spagnuolo PA, MacLean N, Moran MF, Datti A, Wrana J, Batey RA, Schimmer AD (2011) A small-molecule inhibitor of D-cyclin transactivation displays preclinical efficacy in myeloma and leukemia via phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Blood 117: 1986–1997.

Mao X, Liang SB, Hurren R, Gronda M, Chow S, Xu GW, Wang X, Beheshti Zavareh R, Jamal N, Messner H, Hedley DW, Datti A, Wrana JL, Zhu Y, Shi CX, Lee K, Tiedemann R, Trudel S, Stewart AK, Schimmer AD (2008) Cyproheptadine displays preclinical activity in myeloma and leukemia. Blood 112: 760–769.

Mao X, Stewart AK, Hurren R, Datti A, Zhu X, Zhu Y, Shi C, Lee K, Tiedemann R, Eberhard Y, Trudel S, Liang S, Corey SJ, Gillis LC, Barber DL, Wrana JL, Ezzat S, Schimmer AD (2007) A chemical biology screen identifies glucocorticoids that regulate C-Maf expression by increasing its proteasomal degradation through up-regulation of ubiquitin. Blood 110: 4047–4054.

May MJ, Ghosh S (1998) Signal transduction through NF-kappaB. Immunol Today 19: 80–88.

Monzote Fidalgo L, Montalvo Alvarez AM, Geigel LF, Perez Pineiro R, Suarez Navarro M, Rodriguez Cabrera H (2004) Effect of thiadiazine derivatives on intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania amazonensis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 99: 329–330.

Murray RZ, Norbury C (2000) Proteasome inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Anticancer Drugs 11: 407–417.

Nolan GP, Ghosh S, Liou HC, Tempst P, Baltimore D (1991) DNA binding and I kappa B inhibition of the cloned P65 subunit of NF-kappa B, a Rel-related polypeptide. Cell 64: 961–969.

Perez R, Rodriguez H, Perez E, Suarez M, Reyes O, Gonzalez LJ, Lopez de Cerain A, Ezpelata O, Perez C, Ochoa C (2000) Study on the decomposition products of thiadiazinthione and their anticancer properties. Arzneimittelforschung 50: 854–857.

Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC (2009) Multiple myeloma. Lancet 374: 324–339.

Radwan AA, Al-Dhfyan A, Abdel-Hamid MK, Al-Badr AA, Aboul-Fadl T (2012) 3,5-Disubstituted thiadiazine-2-thiones: new cell-cycle inhibitors. Arch Pharm Res 35: 35–49.

Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W (1999) Ikappab kinases phosphorylate NF-KappaB P65 subunit on Serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J Biol Chem 274: 30353–30356.

Tully JE, Nolin JD, Guala AS, Hoffman SM, Roberson EC, Lahue KG, van der Velden J, Anathy V, Blackwell TS, Janssen-Heininger YM (2012) Cooperation between classical and alternative NF-KappaB pathways regulates proinflammatory responses in epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47: 497–508.

Vermeulen L, De Wilde G, Van Damme P, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G (2003) Transcriptional activation of the NF-KappaB P65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (Msk1). EMBO J 22: 1313–1324.

Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A (2005) Phosphorylation of NF-KappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation. Trends Biochem Sci 30: 43–52.

Wang D, Westerheide SD, Hanson JL, Baldwin AS Jr. (2000) Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced phosphorylation of Rela/P65 on Ser529 is controlled by casein kinase Ii. J Biol Chem 275: 32592–32597.

Whiteside ST, Epinat JC, Rice NR, Israel A (1997) I kappa B epsilon, a novel member of the I kappa B family, controls Rela and Crel NF-Kappa B activity. EMBO J 16: 1413–1426.

Yang F, Tang E, Guan K, Wang CY (2003) Ikk beta plays an essential role in the phosphorylation of Rela/P65 on serine 536 induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 170: 5630–5635.

Yinjun L, Jie J, Yungui W (2005) Triptolide inhibits transcription factor Nf-kappaB and induces apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Res 29: 99–105.

Zhang Z, Du X, Zhao C, Cao B, Zhao Y, Mao X (2013) The antidepressant amitriptyline shows potent therapeutic activity against multiple myeloma. Anticancer Drugs 24: 792–798.

Zhong H, May MJ, Jimi E, Ghosh S (2002) The phosphorylation status of nuclear NF-Kappa B determines its association with Cbp/P300 or Hdac-1. Mol Cell 9: 625–636.

Acknowledgements

This project was partly supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81272632, 81101795, 81071935, 81320108023), the Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (BK2011268, BK2010218), the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB933501), the Suzhou City Science and Technology Program (SS201033), and the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author contributions

GC, BC, and XM designed the research. XM and GC wrote the manuscript. GC, KH, XX, XD, ZZ, JT, MS, MW, and JL performed the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Han, K., Xu, X. et al. An anti-leishmanial thiadiazine agent induces multiple myeloma cell apoptosis by suppressing the nuclear factor kappaB signalling pathway. Br J Cancer 110, 63–70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.711

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.711

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

USP15 inhibits multiple myeloma cell apoptosis through activating a feedback loop with the transcription factor NF-κBp65

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2018)

-

SZC017, a novel oleanolic acid derivative, induces apoptosis and autophagy in human breast cancer cells

Apoptosis (2015)