Abstract

Background:

Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) promote metastasis as well as local growth of pancreatic cancer. However, the factors mediating the effect of PSCs on pancreatic cancer cells have not been clearly identified.

Methods:

We used a modified Boyden chamber assay as an in vitro model to investigate the role of PSCs in migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells and to identify the underlying mechanisms.

Results:

PSC supernatant (PSC-SN) dose-dependently induced the trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells, mainly via haptokinesis and haptotaxis, respectively. In contrast to poly-L-lysine or fibronectin, collagen I resembled PSC-SN with respect to its effect on cancer cell behaviours, including polarised morphology, facilitated adhesion, accelerated motility and stimulated trans-migration. Blocking antibodies against integrin α2/β1 subunits significantly attenuated PSC-SN- or collagen I-promoted cell trans-migration and adhesion. Moreover, both PSC-SN and collagen I induced the formation of F-actin and focal adhesions in cells, which was consistent with the constantly enhanced phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK, Tyr397). Inhibition of FAK function by an inhibitor or small interference RNAs significantly diminished the effect of PSC-SN or collagen I on haptotaxis/haptokinesis of pancreatic cancer cells.

Conclusion:

Collagen I is the major mediator for PSC-SN-induced haptokinesis of Panc1 and haptotaxis of UlaPaCa by activating FAK signalling via binding to integrin α2β1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Pancreatic cancer ranks as the 4th–5th in developed countries (Ferlay et al, 2010). The defining feature as well as the histological hallmark of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the profound desmoplastic reaction surrounding the tumour tissue (Mollenhauer et al, 1987; Bardeesy and DePinho, 2002).

Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) have been identified as the key fibrogenic cells in pancreas (Apte et al, 2004; Bachem et al, 2005). In normal pancreas, PSCs are quiescent characterised by numerous perinuclear fat-droplets, a low mitotic index and low synthesis capacity of extracellular matrix (ECM; Apte et al, 1998; Bachem et al, 1998). During pancreatic injury, PSCs transform to a myofibroblast-like phenotype, which are present in the fibrotic area of injured pancreas, lose retinoid-containing droplets, express α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), have a high mitotic index and a high capacity to produce ECM proteins, cytokines and growth factors.

Nowadays, increasing attention is being paid to the interaction between PSCs and cancer cells in the progression of PDAC. Our previous work shows that pancreatic cancer cells stimulate the motility, proliferation and matrix synthesis of PSCs in a paracrine way, via soluble factors including transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), fibroblast growth factor-2 and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF); vice versa, activated PSCs accelerate cancer cell proliferation in vitro, induce tumour invasion in CAM assay and support subcutaneous tumour growth in nude mouse models (Bachem et al, 2005, 2008; Schneiderhan et al, 2007). In line with our findings, other groups (Hwang et al, 2008; Vonlaufen et al, 2008) also show that in vitro PSC supernatant (PSC-SN) stimulates migration, invasion and colony formation of pancreatic cancer cells, whereas in vivo co-injection of cancer cells with PSCs into orthotopic murine models results in increased primary tumour incidence, size, as well as distant metastasis. Xu et al (2010) even suggest that PSCs are able to accompany cancer cells to metastatic sites and stimulate angiogenesis. The above findings demonstrate a reciprocal interaction: PSCs are recruited and activated by pancreatic cancer cells, which in turn produce a beneficial environment to promote local tumour growth and metastatic expansion. However, the precise biological mechanisms involved in PSC-induced malignancy, in particular in the induction of metastasis, are still elusive.

In this study, we applied a modified Boyden chamber assay as an in vitro model to investigate the effect of PSCs on trans-migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Basically, four forms of cell locomotion could be characterised in this assay. Chemotaxis is induced by adding soluble chemokines to the lower chamber, chemokinesis by adding to both upper and lower chambers, haptotaxis by coating the underside of membrane with substratum-bound factors while haptokinesis is by coating both sides of the membrane (Klominek et al, 1993; Douglas-Escobar et al, 2012). Pancreatic stellate cells produce excessive amounts of ECM proteins (fibronectin, collagen I, III) as well as multiple soluble chemokines. Each type of locomotion described above might be induced in pancreatic cancer cells. We demonstrate that the haptotaxis/haptokinesis of cancer cells, rather than the chemotaxis/chemokinesis, was induced by PSCs and identify collagen I as the crucial mediator of this process. These data define a novel mechanism underlying PSC-promoted progress of pancreatic cancer.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Reagents were purchased from the following sources: DMEM/Ham’s F12, L-glutamine with penicillin/streptomycin, Trypsine/EDTA (1 × ), bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from PAA (Pasching, Austria); fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Invitrogen (Paisley, UK); anti-paxillin, anti-focal adhesion kinase (FAK), anti-integrin α1, anti-integrin α2, anti-integrin β1, anti-integrin α2β1 were from Millipore (Temecula, CA, USA); ant-phospho-FAK (Tyr397) was from BD (Bedford, MA, USA); rabbit anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 594, Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA); horseradish peroxidase (HRP) swine anti-rabbit, HRP rabbit anti-mouse were from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark); FAK inhibitor II (PF-573228) was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA, USA); Hoechst 33258, anti-β-tubulin, laminin, poly-L-lysine hydrobromide were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA); collagen AP1 was from Matrix BioScience (Morlenbach, Germany); fibronectin was from EMP Genetech (Ingolstadt, Germany); H-Arg-Gly-Asp-OH peptide (RGD) was from Bachem AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland); small interference RNA (siRNA) and HiPerFect Transfection Reagent were from Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA).

Cell isolation and culture

Human PSCs were isolated by out-growth method (Bachem et al, 1998). Cell purity was assessed by morphology (>90% cells were stellate-like with cytoplasmic extensions; others were spindle shaped), and cytofilament stainings of α-SMA (>95%), vimentin (100%) and desmin (20–40%). Pancreatic stellate cells between 3 and 8 passages were used for the experiments.

Pancreatic cancer cell lines Panc1, MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). UlaPaCa cells were established in our own lab from a peritoneal metastasis of a 71-year-old female patient with PDAC (Haag et al, 2011). Both PSCs and cancer cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium containing 10% FBS, L-glutamine (2 mmol l–1), 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1.25 μg ml–1 amphotericin B, at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Preparation of PSC-conditioned medium

Subconfluent PSCs in 75 cm2 flasks were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, 10 ml of DMEM/Ham’s F12 free of FBS was added and conditioned for 48 h. The conditioned supernatant from PSCs (PSC-SN) was collected, centrifuged at 2000 r.p.m., 4 °C for 10 min and stored at −20 °C. In the following experiments, PSC-SN was diluted with serum-free medium (SFM) as indicated to evaluate the effect of PSC secretions on the biology of cancer cells.

Gene silencing by siRNA

Panc1 cells growing in normal culture medium at 40–50% confluence were transfected with siRNA against human FAK (5′-CCGGTCGAATGATAAGGTGTA-3′) using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two FAK siRNAs were applied separately and a non-silencing siRNA was used as a negative control for nonspecific silencing events. The final concentration of siRNA was 40 nM. After 48 h, transfected cells were maintained in fresh medium containing 1% FBS for additional 18 h before further experimentation. To confirm the inhibition of FAK expression as well as the decreased level of phosphorylated-FAK, a time-course western blot was used. The silencing effect became significant 66 h after siRNA transfection (data not shown).

Cell adhesion assay

Cells were seeded (4 × 104 per well) in a 24-well plates, which was filled with SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN. After 1-h incubation, non-adherent cells were removed by washing twice with PBS, whereas adhered cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and then stained with Hoechst 33258 (2 μg ml–1) for 3 min. Nine random fields from each well were taken for digital images and the number of adherent cells was counted at × 100 magnification.

Cell migration assay

Cell migration was assayed by using modified Boyden chambers (Corning incorporation, Corning, NY, USA) with 8 μm pore polycarbonate membrane. Lower chambers were filled with 650 μl SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN, the inserts were then placed into these media-containing chambers and pre-incubated at 37 °C for at least 20 min. Afterward, cells (1 × 105 per well) in 200 μl SFM were seeded into the inserts, and allowed to trans-migrate for 18 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Non-migratory cells on the upper side of the membrane were scraped off with wet cotton swabs. Migrated cells on the underside of the membrane were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst 33258. Fluorescence photographs were taken in seven random fields at × 100 magnification.

Single-cell tracking assay

Cells (2 × 104 per well) were seeded in a 12-well plate, which was filled with SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN. After 1-h adhesion, the culture plate was placed into a temperature and CO2-controlled incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). Time-lapse images were acquired ( × 64 magnification) every 15–30 min for 24 h under the control of Cell R Imaging software (Olympus Biosystems, Planegg, Germany). Time-lapse movie was taken thereafter. For each movie, at least 30 single cells were randomly selected and manually tracked using ImageJ 1.44m (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Cell velocity, defined as the length of migration trajectory divided by time, was calculated from the trace of each cell and analysed in Excel.

Preparation of coated surfaces

To coat culture plates, poly-L-lysine (22 μg ml–1), collagen I (1 μg ml–1 or 10 μg ml–1) or fibronectin (10 μg ml–1) diluted with PBS were added into each well and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Afterward, the coated surfaces were thoroughly rinsed with PBS and ddH2O twice, respectively, and were air-dried before adding medium or cells.

For haptotaxis in modified Boyden chamber, the insert was filled with 100 μl PBS and floated in the lower chamber containing 650 μl poly-L-lysine, collagen I or fibronectin in PBS. After 1-h incubation at 37 °C, the insert was rinsed with PBS and ddH2O on both sides, air-dried, and placed in another free chamber so that the underside of the membrane with higher concentration of protein faced the lower chamber. For haptokinesis, the insert was filled with the same coating solution as in the lower chamber so that both sides of the membrane were coated with the same concentration of protein, then followed by the other steps as for haptotaxis.

In one experiment (Figure 4B), the polycarbonate membrane was coated with PSC-SN 1 h before cell seeding. The insert was filled with 100 μl SFM (for haptotaxis) or 50% PSC-SN (for haptokinesis) and floated in the lower chamber containing 650 μl 50% PSC-SN. After 1-h incubation at 37 °C, the insert was rinsed with SFM on both sides and then directly applied to the experiment.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared as described before (Zhou et al, 2004). In all, 20–30 μg proteins were separated on 6% or 8% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% BSA in 0.1% PBST for 30 min at room temperature. The blots were probed with following antibodies: integrin α1, integrin α2, integrin β1, β-tubulin, phospho-FAK (Tyr397) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated second antibodies for 45 min. Detection of the proteins was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA).

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips (with or without pre-coating of adhesive molecules), and in the presence of SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN. After 3 h, non-adherent cells were washed away by PBS, whereas adherent cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. After permeabilisation of cells with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 10 min, nonspecific binding was blocked with a buffer containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.5% BSA for 30 min. The cells were then incubated with anti-paxillin (1 : 100) or anti-pFAK (Tyr397; 1 : 50) for 1 h, followed by rabbit-anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 594 (1 : 100, 45 min). Thereafter, F-actin was labelled with phalloidin-Alexa 488 (1 : 200) for 30 min. The nuclei were counter stained with Hoechst 33258. Each incubation step was followed by washing with 0.05% PBST three times for 15 min. Digital fluorescence images were obtained by epifluorescence microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as means±s.e.m. Statistical significances were analysed by two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with a Fisher’s LSD post hoc test. Significant difference was defined as P<0.05.

Results

PSC-SN induces trans-migration of pancreatic cancer cells mainly by promoting cell adhesion and haptokinesis/haptotaxis

PSC-SN dose-dependently induced trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells (Figure 1A). This effect of PSC-SN was significant already at a concentration of 25%. A maximum effect was observed by 75% PSC-SN, which was comparable to that induced by 10% FBS. In all, 50% PSC-SN was mainly used in the following experiments.

Effect of PSC-SN on the process of pancreatic cancer cell trans-migration. (A) Modified Boyden chamber assay. The lower compartment was filled with SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or PSC-SN at varying concentrations. Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were seeded into the inserts and allowed to trans-migrate for 18 h. Representative images for each condition are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm. (B) Cell adhesion assay of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding SFM controls. &P<0.05 compared with 10% FBS. (C) Motility of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were evaluated by single-cell tracking assays. Schematic depiction of two approaches is shown in the middle. In protocol a, cells were seeded in medium containing 10% FBS and cultured for 24 h, followed by 12-h starvation in SFM (to slow down baseline cell motility), and then stimulated by 50% PSC-SN or 10% FBS or SFM for 3 h. In protocol b, cells were directly seeded in SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN, and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Cell migration in both protocols was recorded over 24 h. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding SFM controls.

To examine the effect of PSC-SN on the major events involved in cell trans-migration, the adhesion and random motility of cancer cells were studied by adhesion and single-cell tracking assays, respectively.

As shown in Figure 1B, 50% PSC-SN facilitated adhesion of both cell lines on plastic tissue culture plates. Compared with SFM, the number of adherent cells was 2.2-fold higher for Panc1 (P<0.05) and 1.8-fold higher for UlaPaCa (P<0.05) in the presence of 50% PSC-SN.

Two approaches in single-cell tracking assays were used (Figure 1C middle), which resulted in different effects of PSC-SN on random cancer cell motility. Figure 1C–left shows that PSC-SN slightly stimulated the random motility of both cell lines (relative to SFM: 1.9-fold increase in Panc1, 1.6-fold in UlaPaCa). However, the effect of PSC-SN was significantly smaller (P<0.05) compared with the stimulation from 10% FBS (relative to SFM: 4.2-fold increase in Panc1, 4.0-fold in UlaPaCa). Figure 1C–right shows that PSC-SN significantly accelerated the velocity of both cell lines (P<0.05 compared with SFM: 7.2-fold increase in Panc1, 6.1-fold increase in UlaPaCa). Moreover, the stimulatory effect of PSC-SN was comparable to that of 10% FBS.

As the essential difference between the two protocols, cell adhesion is mediated by 10% FBS in protocol a whereas by PSC-SN in protocol b. In protocol a, PSC-SN was used as a pure ‘motility-stimulator’ of cells already adherent. In protocol b, the addition of PSC-SN to cells was concomitant with cell seeding, so that PSC-SN affected both the adhesion and motility. The tremendously increased velocity of cancer cells in protocol b suggests that PSC-SN-mediated adhesion was crucial for its subsequent effect on motility. Acceleration of cell motility by PSC-SN appears to be critically dependent on specific adhesive molecules (e.g., matrix proteins) rather than soluble factors (e.g., cytokines).

Next, we designed an experimental setting to further define the role of adhesive molecules in PSC-SN (Figure 2A, left panel): Group i insert was pre-incubated in SFM or 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN for 1 h while group ii was placed immediately before cell seeding without pre-treatment with the media. As shown in Figure 2A (right panel), a considerable number of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells in both groups trans-migrated towards 10% FBS, which was used as a positive chemoattractant. In group i, 50% PSC-SN-induced cancer cell trans-migration at a comparable level to 10% FBS. However, PSC-SN showed only a minor effect in group ii. Thus, (1) the pre-coating of inserts with adhesive molecules in PSC-SN is required for PSC-SN-promoted cell trans-migration; and (2) soluble factors in PSC-SN are less efficient compared with those in 10% FBS to induce cancer cell chemotaxis. The next set of experiment was performed to further verify these findings.

Characterisation of the effect of PSC-SN on haptokinesis/haptotaxis vs chemokinesis/chemotaxis of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells. Schematic illustration of the experiments is shown on the left. (A) The lower compartment of Boyden chamber was filled with SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN. Group i insert was pre-incubated in the above media for 1 h. This procedure allowed adhesive molecules in the media to coat the underside of the inserts. Group ii was left outside till 1 h later. Cells were then seeded and allowed to trans-migrate for 18 h. (B) Inserts were placed into lower chambers containing SFM or 50% PSC-SN and incubated for 1 h. Thereafter the lower chambers were exchanged, so that PSC-SN-coated inserts placed into SFM whereas SFM-embedded inserts into PSC-SN. Representative images for each condition are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm.

Inserts were placed into lower chambers in the presence of SFM or 50% PSC-SN, and incubated for 1 h (Figure 2B, left panel). The lower chambers were subsequently exchanged in order to separate, to some degree, adhesive molecules and soluble factors in PSC-SN into two chamber systems. There was significant cell trans-migration through the PSC-SN-coated inserts towards SFM (Figure 2B, right panel). In contrast, without coating of the inserts, few cells trans-migrated towards PSC-SN used as a chemoattractant. This observation suggests a strong haptokinetic/haptotactic effect but a poor chemotactic effect of PSC-SN on cancer cells.

Collagen I is as effective as PSC-SN in promoting haptokinesis/haptotaxis of pancreatic cancer cells

Next, we aimed to identify the adhesive molecule(s) responsible for PSC-SN-induced cancer cell hapto-migration (haptokinesis/haptotaxis). Collagen I and fibronectin, the most abundant ECM proteins produced by PSCs in PDAC (Apte et al, 2004; Bachem et al, 2005), appeared to be the most promising mediators in PSC-SN.

After coating culture wells with collagen I, cancer cell adhesion in the presence of SFM or 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN was all improved and comparable to each other (Figure 3A). Improved adhesion was most significant for cells in SFM adherent on collagen I (P<0.05). In contrast, fibronectin showed no further stimulatory effect (Figure 3A), and neither did laminin (data not shown). In addition, both collagen I- and PSC-SN-mediated cell adhesion were not affected by a RGD peptide (Figure 3B), which contains the integrin-recognition sequence presented in ECM proteins such as fibronectin and vitronectin but not collagens (Humphries et al, 2006; Barczyk et al, 2010). The doses of RGD we used did inhibit the attachment of a melanoma cell line on fibronectin (data not shown). These data demonstrate that collagen I, but not fibronectin, appeared to be mainly involved in PSC-SN-induced adhesion of pancreatic cancer cells.

Effect of matrix proteins on the adhesion and motility of pancreatic cancer cells. Data are representative of results from three independent experiments. (A) In all, 24-well plates were left uncoated or coated with collagen I (Col) and/or fibronectin (Fn) as described in the method. Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were then seeded in SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN, and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. fold of 10% FBS w/o coating. *P<0.05. (B) Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were pre-incubated with RGD peptide (100 or 200 μg ml–1) for 1 h and then applied to cell adhesion assay. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. number of adherent cells. (C) Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were seeded in SFM or medium containing 10% FBS or 50% PSC-SN (SN) with or without pre-coated collagen I. After 1 h adhesion, cell migration was recorded over 24 h. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 compared with w/o coating SFM control; **P<0.05 compared with collagen I coating SFM control; &P<0.05. (D) In all, 12-well plates were pre-coated with poly-L-lysine (PLL), fibronectin, or collagen I. Panc1 and UlaPaCa were seeded with 10% FBS and allowed to adhere for 1 h. Afterward the culture plates were washed twice with PBS and SFM were filled in. Cell migration was recorded over 30 h. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding poly-L-lysine coating SFM controls.

The effect of collagen I on cell motility was assessed by single-cell tracking assays. Compared with non-coated conditions, collagen I coating significantly accelerated cancer cell motility in SFM (Panc1: 10.5 vs 23.4 μm h–1; UlaPaCa: 10.5 vs 23.5 μm h–1; P<0.05), as well as in medium containing 10% FBS (Panc1: 27.3 vs 54.9 μm h–1; UlaPaCa: 26 vs 46 μm h–1; P<0.05). However, collagen I coating showed no further stimulation in the presence of PSC-SN, although the motility was still significantly higher than that in SFM with coating (Figure 3C). Thus, (1) collagen I alone is sufficient to stimulate cancer cell motility by providing a substratum; (2) collagen I presented in PSC-SN is sufficient to stimulate cell motility; and (3) besides collagen I, other factors in PSC-SN act synergistically to promote cell motility.

To further evaluate the specificity and efficiency of collagen I on pancreatic cancer cell migration, fibronectin and poly-L-lysine were applied. As a nonspecific adhesive molecule, poly-L-lysine (22 μg ml–1) was as effective as 50% PSC-SN in improving cancer cell adhesion, but did not affect the motility (data not shown). Figure 3D shows that the velocity of cancer cells moving on fibronectin, as well as on poly-L-lysine, was significantly slower than that on collagen I. Thus, collagen I facilitates cell adhesion, and specifically and effectively promotes the motility. Indeed, in contrast to other adhesive molecules, collagen I was as effective as PSC-SN in stimulating hapto-migration of pancreatic cancer cells (Figure 4A). Furthermore, both collagen I- and PSC-SN-induced cell trans-migration were not affected by a RGD peptide (data not shown).

Effect of matrix proteins on the trans-migration of pancreatic cancer cells. (A) Modified Boyden chamber assay of Panc1 cells. The underside of the inserts was left uncoated or coated with poly-L-lysine (PLL) or fibronectin (Fn) or collagen I (Col) as described in the method. The lower compartment of Boyden chamber was filled with SFM or medium containing PSC-SN. Representative images for each condition are shown. (B) Characterisation of the directionality during trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells. Inserts without coating (a, f) were used as a negative control. Other inserts were coated with collagen I or PSC-SN either on both sides (b, g; d, i) or on the underside (c, h; e, j) as described in the Materials and Method. Lower chambers were filled with SFM. Representative images for each condition are shown. (C) Quantification of cell trans-migration under each condition in Figure 4B. Images were taken from seven random fields and cell number was counted with ImageJ 1.44m. Scale bars: 200 μm.

To evaluate cell directionality during trans-migration and differentiate haptokinesis from haptotaxis, Boyden chamber inserts were coated with collagen I or PSC-SN either on both sides or on the underside and the lower chambers were filled with SFM. Figure 4B shows that compared with uncoated inserts (images a and f), coating the inserts with collagen I or PSC-SN on both sides (images b, d, g and i) significantly induced trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa. This indicates that haptokinesis of both cell lines was stimulated. Further stimulation of cell trans-migration was observed when the underside of inserts was coated with collagen I or PSC-SN (images c, e, h and j). This additional stimulation represents cell haptotaxis. Quantification of trans-migrated cells is shown in Figure 4C. In Panc1 cells, haptokinesis accounted for 77% and 54% of collagen I- and PSC-SN-induced trans-migration, respectively. In UlaPaCa cells, haptotaxis was responsible for 60% and 80% of collagen I- and PSC-SN-induced trans-migration, respectively. In conclusion, PSC-SN or collagen I mainly promotes haptokinesis of Panc1, but haptotaxis of UlaPaCa cells.

The effect of collagen I in PSC-SN on pancreatic cancer cells is mediated via integrin α2β1

Pancreatic stellate cell-supernatant and collagen I not only showed similar effect on cell adhesion and migration, but also induced similar morphology. As observed in the adhesion assays (Figure 5A), both PSC-SN and collagen I efficiently promoted cell spreading, whereas cells seeded in SFM or on poly-L-lysine were merely small and round. Moreover, compared with cancer cells in FBS, which were circumferential or polygonal, cells in the presence of PSC-SN or on collagen I were polarised exhibiting lamellipodia.

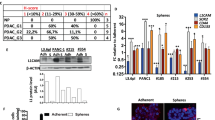

Integrin α 2 β 1 mediates the stimulatory effect of PSC-SN or collagen I on pancreatic cancer cells. (A) Morphology of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells in cell adhesion assay. In all, 12-well plates were left uncoated or were coated with poly-L-lysine (PLL) or collagen I (Col). Representative phase contrast images for each condition are shown. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Thirty microgram of total cell lysates from Panc1, UlaPaCa (Ula), MiaPaCa-2 (Mia) and AsPC-1 cultured with 10% FBS for 24 h were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE. Antibodies against human α1, α2 and β1 integrin subunits were used to detect the corresponding expression. The band of PSCs (arrow) was shown as a positive control for α1 integrin. β-tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells were pre-incubated with 5 μg ml–1 integrin α2β1 blocking antibody for 1 h, and then were allowed to adhere for 1 h in SFM (with or w/o coated collagen I) or medium containing 50% PSC-SN. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding controls w/o antibodies. (D) UlaPaCa cells were pre-incubated with 20 μg ml–1 integrin α2 and/or β1 blocking antibodies for 1 h. The cells were then allowed to trans-migrate for 18 h towards pre-coated collagen I on the underside of the inserts or towards 50% PSC-SN. Representative images for each condition are shown. Scale bars: 200 μm.

The major receptors mediating ECM-cell interactions are integrins, a family of heterodimeric trans-membrane proteins composed of non-covalently associated α and β subunits (Hynes, 2002). Integrin ligand specificity is determined by the α subunit, whereas the β subunit is connected to cytoskeleton and initiates intracellular signalling pathways (Humphries et al, 2006). Among the 24 different α–β combinations, collagens are recognised by integrins α1β1, α2β1, α10β1 and α11β1, with the former two most widely studied (Hynes, 2002; Barczyk et al, 2010). Western blot was used to analyse integrin expression in Panc1, UlaPaCa, MiaPaCa-2 and AsPC-1 cells. Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells expressed both α2 and β1 subunits; MiaPaCa-2 expressed less α2; AsPC-1 presented a very faint band of β1 subunit (Figure 5B). In accordance with the data of Grzesiak and Bouvet (2006), none of the tested cells expressed the α1 subunit (Figure 5B). Thus, integrin α2β1 represents the major collagen I receptor on Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells.

Indeed, adhesion of both cell lines on collagen I was completely blocked by an anti-integrin α2β1 antibody (Figure 5C). Furthermore, cell adhesion in the presence of PSC-SN was markedly attenuated (59% decrease in Panc1 and 66% in UlaPaCa), indicating that collagen I is the major mediator for PSC-SN-promoted cell adhesion via integrin α2β1.

To further examine whether collagen I was responsible for PSC-SN-induced cancer cell trans-migration, α2 and/or β1 subunit blocking antibodies were used in modified Boyden chamber assays. The anti-integrin α2 antibody abolished UlaPaCa haptotaxis induced by collagen I, but showed a limited blocking effect against stimulation by PSC-SN (Figure 5D). In contrast, anti-integrin β1 antibody significantly inhibited PSC-SN-induced UlaPaCa haptotaxis. This inhibition was even more obvious upon combination of anti-integrin α2 and β1 antibodies. Although the involvement of other molecules in PSC-SN should not be excluded, these data support that collagen I is the major component in PSC-SN that mediates the stimulation via integrin α2β1.

FAK signalling is involved in PSC-derived, collagen I-induced haptokinesis /haptotaxis of pancreatic cancer cells

Cancer cell migration on culture plates in the presence of PSC-SN or pre-coated collagen I followed the common multistep cycle, which began with the protrusion of membrane at cell front, followed by translocation of cell body, and finally the release and traction of cell rear (Supplementary Material Movie 1 and 2). To figure out the intracellular mechanisms underlying cell haptokinesis, fluorescence microscopy of F-actin, phospho-FAK (pFAK) and paxillin was performed. After stimulation with PSC-SN or collagen I, a strong formation of F-actin in the cell body and actin polymerisation in the lamellipodia were clearly observed in Panc1 (Figure 6) and UlaPaCa cells (data not shown). Moreover, pFAK and paxillin, two of the major scaffold proteins in focal adhesions (Schlaepfer et al, 2004), were significantly distributed on cell periphery. In cells in SFM (data not shown) or on poly-L-lysine, however, pFAK and paxillin were aggregated within the cytoplasm, and focal adhesions were hardly observed. These data imply that PSC-SN and collagen I initiate the coordinated and dynamic regulation of focal adhesions and cytoskeleton networks, which is required for efficient migration of pancreatic cancer cells.

Fluorescence stainings of pFAK, paxillin and F-actin in Panc1 cells. Glass coverslips were placed in six-well plates and coated with poly-L-lysine (PLL) or collazgen I (Col). Panc1 cells were allowed to adhere in SFM (with PLL/Col coating) or medium containing 50% PSC-SN (w/o coating) for 3 h. The cells were then stained with anti-pFAK (Tyr397) or anti-paxillin (red) and rhodamine-phalloidin (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). In each image, the boxed region is shown magnified in the insert. Arrows indicate representative focal adhesions, and asterisks indicate representative lamellipodia. Scale bars: 40 μm.

To investigate the involvement of FAK activity in cancer cell haptokinesis, cell lysates were collected at various time points after cell seeding in SFM with or without pre-coated collagen I or poly-L-lysine, or medium containing 50% PSC-SN. Phosphorylation of FAK (Tyr397) was examined by western blot. Just 10 min after seeding (Figure 7A), FAK in Panc1 cells stimulated by PSC-SN or collagen I was strongly phosphorylated, and this activity remained at a significantly higher level compared with cells in SFM. For cells seeded on poly-L-lysine, FAK phosphorylation was also increased within 10 min but returned to a low level thereafter, indicating a transient stimulation by mechanical performance. UlaPaCa cells showed similar results to Panc1 cells (Supplementary Figure S1). Interestingly, the enhanced and sustained phosphorylation of FAK corresponds to the constantly higher cell motility induced by PSC-SN or collagen I in single-cell tracking assays (Figure 7B).

FAK signalling pathway is involved in PSC-SN- or collagen I-induced haptokinesis/haptotaxis of pancreatic cancer cells. (A) Panc1 cells were seeded in SFM (with or w/o coated poly-L-lysine or collagen I) or 50% PSC-SN. The culture was stopped at indicated time points after cell seeding. Both non-adherent and adherent cells were collected and lysed. Twelve microgram of total lysates were subjected to 6% SDS-PAGE, and pFAK (Tyr397) was used to detect the activation of this kinase. The same blots were re-probed with antibody against total FAK as loading controls. Quantification of pFAK was performed by scanning densitometry from three independent experiments, and presented as mean±s.e.m. fold increase above w/o coating SFM. ( SFM, poy-L-lysine, collagen I, 50% PSC-SN). (B) Velocity profile of Panc1 cells migrating under the above conditions was obtained from 24-h single-cell tracking assay. (C) Panc1 and UlaPaCa were pre-incubated with 1% DMSO or 1 μ M PF-537228 (PF) for 1 h. The cells were then allowed to trans-migrate for 18 h towards SFM, 10% FBS, pre-coated collagen I (Col) on the underside of the inserts, or 50% PSC-SN. Representative images for each condition are shown. (D) Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells pre-treated with DMSO or PF-537228 were seeded in SFM (with or w/o coated collagen I) or medium containing 50% PSC-SN. Single-cell tracking assay was performed after 1-h adhesion. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. from three independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared with corresponding 0.1% DMSO controls. (E) Panc1 cells were transfected with 40 nM negative siRNA, FAK siRNA1 or FAK siRNA2 for 66 h. Inhibition of FAK was confirmed by western blot using β-tubulin as a loading control. A representative blot from three independent experiments is shown (left panel). Effect of collagen I or PSC-SN on migration of FAK-silenced cells was evaluated in modified Boyden chamber assay (middle panel) and single-cell tracking assay (right panel) as described before. Scale bars: 200 μm.

To further examine whether FAK activity is essential for cancer cell haptokinesis, the FAK inhibitor PF-537228 was applied, which inhibits FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation. In Boyden chamber assays (Figure 7C), PSC-SN- or collagen I-induced haptokinesis of Panc1 and haptotaxis of UlaPaCa was significantly inhibited, whereas FBS-stimulated chemotaxis of both cell lines was unaffected. As essential steps involved in trans-migration, cell motility accelerated by PSC-SN or collagen I was significantly attenuated by PF-573228 (Figure 7D), whereas adhesion was somewhat decreased (Supplementary Figure S2). Next, siRNA-mediated gene silence of FAK was performed in Panc1 cells. After transfection with either of the two FAK siRNAs, the expression of FAK as well as the level of phosphorylated-FAK was decreased (Figure 7E). Consequently, both PSC-SN- and collagen I-stimulated haptokinesis and random motility were significantly inhibited by siRNA treatment (Figure 7E).

In conclusion, the obtained data demonstrate that PSC-SN-induced hapto-migration of pancreatic cancer cells is based on collagen I-integrin α2β1-FAK signalling pathway.

Discussion

Activated PSCs synthesise multiple cytokines and growth factors. Connective tissue growth factor (Eguchi et al, 2012), stromal cell-derived factor-1 (Li et al, 2012) and activin (Lonardo et al, 2012) are addressed in PSC-induced migration or invasion of pancreatic cancer cells. Besides, PSCs produce PDGF (Vonlaufen et al, 2008), VEGF (Xu et al, 2010), TGF-β1 (Shek et al, 2002), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (Masamune et al, 2002) and COX-2 (Yoshida et al, 2005), which may potentiate cancer cell migration. In our experimental system, however, the conditioned medium from PSCs induced haptokinesis or haptotaxis of pancreatic cancer cells rather than chemokinesis or chemotaxis. This conclusion is based on two major findings: (1) PSC-SN-mediated cell adhesion was a prerequisite for the strong stimulation of random motility of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells. As a chemokinetic stimulator, PSC-SN was much less efficient compared with 10% FBS in accelerating cell motility. (2) Pre-incubation of inserts in PSC-SN was necessary and sufficient to induce trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells in modified Boyden chamber assays. Upon depletion of adhesive molecules, PSC-SN as a pure chemoattractant only weakly induced cell trans-migration. Thus, it is reasonable to deduce that PSC-SN-promoted trans-migration of cancer cell by providing adhesive molecule(s) to the interface of inserts, which in turn facilitated cell adhesion and then accelerated the motility. This type of migration, which is associated with the substrate-bound molecules, closely resembles the biology of haptokinesis/haptotaxis.

In breast cancer, haptotactic guidance from interstitial scaffolds is now considered to be one of the important mechanisms for cancer cell invasion (Gritsenko et al, 2012). The combined use of multiphoton and second-harmonic imaging shows that metastatic mammary cells migrate rapidly in vivo and are closely associated with collagen-containing fibres (Wang et al, 2002). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is a particularly stroma-rich cancer. Instead of a mere bystander, PSCs together with the extensive ECM have a critical role in PDAC progression (Apte et al, 2012; Feig et al, 2012). Recent in vivo studies demonstrate that PSCs promote not only the local tumour growth (Bachem et al, 2005), but more strikingly metastasis of PDAC (Vonlaufen et al, 2008). Our data, indicating that PSC-SN stimulate cell haptokinesis/haptotaxis, unravel one possible mechanism involved in pancreatic cancer metastasis. The implication of this mechanism is important when considering that PSCs may accompany cancer cells during dissemination (Xu et al, 2010) and provide tumour-favourable substratum to support cell survival and migration.

Collagen I is the major adhesive molecule in PSC-SN inducing haptokinesis of Panc1 and haptotaxis of UlaPaCa. This is proven by four points: (1) collagen I is as effective as PSC-SN in promoting adhesion, random motility and trans-migration of Panc1 and UlaPaCa. This stimulatory effect was not induced by other matrix proteins (fibronectin, laminin) secreted from PSCs. (2) In contrast to poly-L-lysine, a nonspecific substratum, collagen I specifically stimulated cancer cell migration besides its well-known effect on cell adhesion. Cells stimulated by PSC-SN and collagen I showed a similar motile phenotype characterised by the polarised morphology. (3) Blocking antibodies against integrin α2β1, the primary receptor for collagen I on Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells, significantly attenuated the stimulatory effects of PSC-SN. However, the RGD peptide, as a competitive inhibitor for fibronectin, did not affect PSC-SN-induced cell adhesion or migration. (4) UlaPaCa trans-migration was markedly accelerated only in the presence of a concentration gradient of pre-coated collagen I or PSC-SN, indicating haptotaxis is its major motile response. In Panc1 cells, a strong stimulation was observed even in the absence of such a gradient, suggesting haptokinesis is mainly responsible for the induced trans-migration.

In other cancers with strong desmoplasia (breast, prostate, lung cancer and so on), collagen I is shown to be the key component of stroma in both primary and metastatic sites (Egeblad et al, 2010), and has a vital role in the development and progression of cancers (Shintani et al, 2008; Cheng and Leung, 2011; Cox et al, 2013). In PDAC, collagen I is more frequently associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT; Koenig et al, 2006; Shintani et al, 2006; Imamichi et al, 2007), which is proposed to be a critical mechanism for the acquisition of malignant phenotypes by epithelial cancer cells (Thiery, 2002). However, EMT is a time-consuming cellular process, which consists of multiple biochemical events, such as activation of transcription factors, expression of specific cell-surface proteins, reorganisation and expression of cytoskeletal proteins, and changes in the expression of specific microRNAs (Kalluri and Weinberg, 2009). Our study shows that after a rather short stimulation by collagen I or PSC-SN (<1 h), cell adhesion, spreading and migration were significantly initiated, indicating a distinct mechanism rather than EMT is involved in the pro-migratory effect of collagen I and PSC-SN.

One study (Grzesiak and Bouvet, 2006) also showed in eight pancreatic cell lines that collagen I promoted the strongest adhesion, proliferation and migration compared with other substrates tested. Consistent with their data, we identify collagen I as a major component responsible for PSC-induced adhesion and migration of pancreatic cancer cells. This is most relevant to the in vivo environment where PSCs are in close proximity to cancer cells and promote tumour progress via a paracrine pathway. Actually, the locomotive activation elicited by collagen I reflects a primary function of PSCs–to produce a scaffold that promotes cell movement. Thus, it is plausible that through de novo synthesis and deposition of collagen I, PSCs accompany and favour pancreatic cancer cell metastasis by providing trails of least resistance for cells to adhere and migrate.

Extracellular matrix proteins induce intracellular signals in large part through integrin receptors (Hynes, 1992). Not only does ECM serve as a biochemical ligand for integrins, the topography and stiffness of ECM also regulates integrin expression and function (Jean et al, 2011) and affects cell movement (Lo et al, 2000). Increased stroma stiffness has been associated with the tumour formation and progression in breast cancer (Keely, 2011). In PDAC, the expression of integrin profile is modulated on cancer cells in accordance with the ECM modification. The expression of α1, α2, α3 and α6 subunits is upregulated in vivo; whereas α2, α3, α5, α6, αv and β1 are expressed on most pancreatic cancer cell lines (Grzesiak et al, 2007). Besides, expressions of integrin α6β1 (Weinel et al, 1995; Vogelmann et al, 1999) and αvβ3 (Hosotani et al, 2002) in pancreatic cancer cell lines and tissues are associated with invasion.

In our study, integrin α2β1 is identified as the motility-promoting receptor for haptokinesis of Panc1 and haptotaxis of UlaPaCa cells. Utilisation of blocking antibody against integrin α2β1 significantly attenuated the stimulatory effect of PSC-SN and collagen I. Integrin-targeted therapy has revealed promising results in both preclinical and clinical studies in breast cancer, melanoma, glioblastoma and other solid tumours (for review, see Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). In PDAC, inhibition of β1 integrin with monoclonal antibody strongly blocked cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro (Arao et al, 2000; Ryschich et al, 2009). In vivo, knockdown of β1 integrin reduced primary tumour growth by 50% and completely inhibited spontaneously occurring metastasis (Grzesiak et al, 2011). Consistently, our data provide additional insights to the combined blockage of integrin α2 and β1 subunits as a potential intervention in PDAC.

Integrin signalling functions are mediated by a variety of intracellular proteins, which are associated with integrin cytoplasmic domains (Liu et al, 2000). Focal adhesion kinase is one of the crucial proteins to transduce signals initiated by ECM–integrin interactions (Schlaepfer et al, 2004). Besides, recent studies delineate FAK as a mechanosensor for the regulation of cell responses to ECM stiffness (Alexander et al, 2008; Plotnikov et al, 2012). Our data reveal that FAK signalling has a vital role in the haptokinetic and haptotactic response of pancreatic cancer cells. In the time-course western blot, PSC-SN and collagen I constantly enhanced the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 in Panc1 and UlaPaCa cells. Inhibition of FAK, either by the phosphorylation inhibitor PF-573228 or by siRNA-mediated gene silencing, significantly attenuated PSC-SN- and collagen I-promoted migration of pancreatic cancer cells. Focal adhesion kinase is increasingly accepted as a potential anticancer target (for review, see Li and Hua, 2008). Both in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that inhibition of FAK resulted in decreased growth, metastasis and chemoresistance of PDAC (Duxbury et al, 2004; Hochwald et al, 2009; Huanwen et al, 2009; Stokes et al, 2011; Ucar et al, 2011). Moreover, a recent phase I trial of a FAK inhibitor in advanced solid tumours confirms its clinical safety and supports further investigation in cancer therapy (Infante et al, 2012).

In summary, we demonstrate here that PSCs promote migration of pancreatic cancer cells mainly via the haptokinetic or haptotactic mechanisms. Collagen I secreted from PSCs, in large part, mediates cell hapto-migration by enhancing α2β1 integrin-FAK signalling pathway. Considering the interaction between PSCs and cancer cells in vivo, our data present a novel mechanism underlying the highly motile and early metastatic behaviours of pancreatic cancer cells, and suggest that integrin α2β1 and FAK are potential targets for preventing PDAC progression.

Change history

21 January 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Alexander NR, Branch KM, Parekh A, Clark ES, Iwueke IC, Guelcher SA, Weaver AM (2008) Extracellular matrix rigidity promotes invadopodia activity. Curr Biol 18: 1295–1299.

Apte MV, Haber PS, Applegate TL, Norton ID, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA, Pirola RC, Wilson JS (1998) Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture. Gut 43: 128–133.

Apte MV, Park S, Phillips PA, Santucci N, Goldstein D, Kumar RK, Ramm GA, Buchler M, Friess H, McCarroll JA, Keogh G, Merrett N, Pirola R, Wilson JS (2004) Desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic cancer: role of pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas 29: 179–187.

Apte MV, Pirola RC, Wilson JS (2012) Pancreatic stellate cells: a starring role in normal and diseased pancreas. Front Physiol 3: 344.

Arao S, Masumoto A, Otsuki M (2000) Beta1 integrins play an essential role in adhesion and invasion of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Pancreas 20: 129–137.

Bachem MG, Schneider E, Gross H, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Menke A, Siech M, Beger H, Grunert A, Adler G (1998) Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology 115: 421–432.

Bachem MG, Schunemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, Zhou S, Schmid-Kotsas A, Adler G (2005) Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology 128: 907–921.

Bachem MG, Zhou S, Buck K, Schneiderhan W, Siech M (2008) Pancreatic stellate cells—role in pancreas cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg 393: 891–900.

Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D (2010) Integrins. Cell Tissue Res 339: 269–280.

Bardeesy N, DePinho RA (2002) Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 897–909.

Cheng JC, Leung PC (2011) Type I collagen down-regulates E-cadherin expression by increasing PI3KCA in cancer cells. Cancer Lett 304: 107–116.

Cox TR, Bird D, Baker AM, Barker HE, Ho MW, Lang G, Erler JT (2013) LOX-mediated collagen crosslinking is responsible for fibrosis-enhanced metastasis. Cancer Res 73 (6): 1721–1732.

Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA (2010) Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 9–22.

Douglas-Escobar M, Rossignol C, Steindler D, Zheng T, Weiss MD (2012) Neurotrophin-induced migration and neuronal differentiation of multipotent astrocytic stem cells in vitro. PLoS One 7: e51706.

Duxbury MS, Ito H, Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, Whang EE (2004) Focal adhesion kinase gene silencing promotes anoikis and suppresses metastasis of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Surgery 135: 555–562.

Egeblad M, Rasch MG, Weaver VM (2010) Dynamic interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 697–706.

Eguchi D, Ikenaga N, Ohuchida K, Kozono S, Cui L, Fujiwara K, Fujino M, Ohtsuka T, Mizumoto K, Tanaka M (2012) Hypoxia enhances the interaction between pancreatic stellate cells and cancer cells via increased secretion of connective tissue growth factor. J Surg Res 181 (2): 225–233.

Feig C, Gopinathan A, Neesse A, Chan DS, Cook N, Tuveson DA (2012) The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 18: 4266–4276.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 127: 2893–2917.

Gritsenko PG, Ilina O, Friedl P (2012) Interstitial guidance of cancer invasion. J Pathol 226: 185–199.

Grzesiak JJ, Bouvet M (2006) The alpha2beta1 integrin mediates the malignant phenotype on type I collagen in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer 94: 1311–1319.

Grzesiak JJ, Ho JC, Moossa AR, Bouvet M (2007) The integrin-extracellular matrix axis in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 35: 293–301.

Grzesiak JJ, Tran CH, Burton DW, Kaushal S, Vargas F, Clopton P, Snyder CS, Deftos LJ, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M (2011) Knockdown of the beta(1) integrin subunit reduces primary tumor growth and inhibits pancreatic cancer metastasis. Int J Cancer 129: 2905–2915.

Haag C, Stadel D, Zhou S, Bachem MG, Moller P, Debatin KM, Fulda S (2011) Identification of c-FLIP(L) and c-FLIP(S) as critical regulators of death receptor-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Gut 60: 225–237.

Hochwald SN, Nyberg C, Zheng M, Zheng D, Wood C, Massoll NA, Magis A, Ostrov D, Cance WG, Golubovskaya VM (2009) A novel small molecule inhibitor of FAK decreases growth of human pancreatic cancer. Cell Cycle 8: 2435–2443.

Hosotani R, Kawaguchi M, Masui T, Koshiba T, Ida J, Fujimoto K, Wada M, Doi R, Imamura M (2002) Expression of integrin alphaVbeta3 in pancreatic carcinoma: relation to MMP-2 activation and lymph node metastasis. Pancreas 25: e30–e35.

Huanwen W, Zhiyong L, Xiaohua S, Xinyu R, Kai W, Tonghua L (2009) Intrinsic chemoresistance to gemcitabine is associated with constitutive and laminin-induced phosphorylation of FAK in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer 8: 125.

Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ (2006) Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci 119: 3901–3903.

Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, Ji B, Evans DB, Logsdon CD (2008) Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res 68: 918–926.

Hynes RO (1992) Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 69: 11–25.

Hynes RO (2002) Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110: 673–687.

Imamichi Y, Konig A, Gress T, Menke A (2007) Collagen type I-induced Smad-interacting protein 1 expression downregulates E-cadherin in pancreatic cancer. Oncogene 26: 2381–2385.

Infante JR, Camidge DR, Mileshkin LR, Chen EX, Hicks RJ, Rischin D, Fingert H, Pierce KJ, Xu H, Roberts WG, Shreeve SM, Burris HA, Siu LL (2012) Safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic phase I dose-escalation trial of PF-00562271, an inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30: 1527–1533.

Jean C, Gravelle P, Fournie JJ, Laurent G (2011) Influence of stress on extracellular matrix and integrin biology. Oncogene 30: 2697–2706.

Kalluri R, Weinberg RA (2009) The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 119: 1420–1428.

Keely PJ (2011) Mechanisms by which the extracellular matrix and integrin signaling act to regulate the switch between tumor suppression and tumor promotion. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 16: 205–219.

Klominek J, Robert KH, Sundqvist KG (1993) Chemotaxis and haptotaxis of human malignant mesothelioma cells: effects of fibronectin, laminin, type IV collagen, and an autocrine motility factor-like substance. Cancer Res 53: 4376–4382.

Koenig A, Mueller C, Hasel C, Adler G, Menke A (2006) Collagen type I induces disruption of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts and promotes proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 66: 4662–4671.

Li S, Hua ZC (2008) FAK expression regulation and therapeutic potential. Adv Cancer Res 101: 45–61.

Li X, Ma Q, Xu Q, Liu H, Lei J, Duan W, Bhat K, Wang F, Wu E, Wang Z (2012) SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling induces pancreatic cancer cell invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro through non-canonical activation of Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Lett 322: 169–176.

Liu S, Calderwood D, Ginsberg M (2000) Integrin cytoplasmic domain-binding proteins. J Cell Sci Pt 20: 3563–3571.

Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL (2000) Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J 79: 144–152.

Lonardo E, Frias-Aldeguer J, Hermann PC, Heeschen C (2012) Pancreatic stellate cells form a niche for cancer stem cells and promote their self-renewal and invasiveness. Cell Cycle 11: 1282–1290.

Masamune A, Kikuta K, Satoh M, Sakai Y, Satoh A, Shimosegawa T (2002) Ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma block activation of pancreatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem 277: 141–147.

Mollenhauer J, Roether I, Kern HF (1987) Distribution of extracellular matrix proteins in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its influence on tumor cell proliferation in vitro. Pancreas 2: 14–24.

Plotnikov SV, Pasapera AM, Sabass B, Waterman CM (2012) Force fluctuations within focal adhesions mediate ECM-rigidity sensing to guide directed cell migration. Cell 151: 1513–1527.

Ryschich E, Khamidjanov A, Kerkadze V, Buchler MW, Zoller M, Schmidt J (2009) Promotion of tumor cell migration by extracellular matrix proteins in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 38: 804–810.

Schlaepfer DD, Mitra SK, Ilic D (2004) Control of motile and invasive cell phenotypes by focal adhesion kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1692: 77–102.

Schneiderhan W, Diaz F, Fundel M, Zhou S, Siech M, Hasel C, Moller P, Gschwend JE, Seufferlein T, Gress T, Adler G, Bachem MG (2007) Pancreatic stellate cells are an important source of MMP-2 in human pancreatic cancer and accelerate tumor progression in a murine xenograft model and CAM assay. J Cell Sci 120: 512–519.

Shek FW, Benyon RC, Walker FM, McCrudden PR, Pender SL, Williams EJ, Johnson PA, Johnson CD, Bateman AC, Fine DR, Iredale JP (2002) Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 by pancreatic stellate cells and its implications for matrix secretion and turnover in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Pathol 160: 1787–1798.

Shintani Y, Hollingsworth MA, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR (2006) Collagen I promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer by activating c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase 1 and up-regulating N-cadherin expression. Cancer Res 66: 11745–11753.

Shintani Y, Maeda M, Chaika N, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ (2008) Collagen I promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells via transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 95–104.

Stokes JB, Adair SJ, Slack-Davis JK, Walters DM, Tilghman RW, Hershey ED, Lowrey B, Thomas KS, Bouton AH, Hwang RF, Stelow EB, Parsons JT, Bauer TW (2011) Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase by PF-562,271 inhibits the growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer concomitant with altering the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Ther 10: 2135–2145.

Thiery JP (2002) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 442–454.

Ucar DA, Cox A, He DH, Ostrov DA, Kurenova E, Hochwald SN (2011) A novel small molecule inhibitor of FAK and IGF-1R protein interactions decreases growth of human esophageal carcinoma. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 11: 629–637.

Vogelmann R, Kreuser ED, Adler G, Lutz MP (1999) Integrin alpha6beta1 role in metastatic behavior of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer 80: 791–795.

Vonlaufen A, Joshi S, Qu C, Phillips PA, Xu Z, Parker NR, Toi CS, Pirola RC, Wilson JS, Goldstein D, Apte MV (2008) Pancreatic stellate cells: partners in crime with pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res 68: 2085–2093.

Wang W, Wyckoff JB, Frohlich VC, Oleynikov Y, Huttelmaier S, Zavadil J, Cermak L, Bottinger EP, Singer RH, White JG, Segall JE, Condeelis JS (2002) Single cell behavior in metastatic primary mammary tumors correlated with gene expression patterns revealed by molecular profiling. Cancer Res 62: 6278–6288.

Weinel RJ, Rosendahl A, Pinschmidt E, Kisker O, Simon B, Santoso S (1995) The alpha 6-integrin receptor in pancreatic carcinoma. Gastroenterology 108: 523–532.

Xu Z, Vonlaufen A, Phillips PA, Fiala-Beer E, Zhang X, Yang L, Biankin AV, Goldstein D, Pirola RC, Wilson JS, Apte MV (2010) Role of pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic cancer metastasis. Am J Pathol 177: 2585–2596.

Yoshida S, Ujiki M, Ding XZ, Pelham C, Talamonti MS, Bell RJ, Denham W, Adrian TE (2005) Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) express cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and pancreatic cancer stimulates COX-2 in PSCs. Mol Cancer 4: 27.

Zhou S, Schmelz A, Seufferlein T, Li Y, Zhao J, Bachem MG (2004) Molecular mechanisms of low intensity pulsed ultrasound in human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 279: 54463–54469.

Acknowledgements

JL was supported by the Chinese Scholarship Committee. This work was supported by Deutsche Krebshilfe eV (grant 109563; HH, MGB, TS). The authors thank Gisela Sailer for excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Zhou, S., Siech, M. et al. Pancreatic stellate cells promote hapto-migration of cancer cells through collagen I-mediated signalling pathway. Br J Cancer 110, 409–420 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.706

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.706

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The tumor microenvironment in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: current perspectives and future directions

Cancer and Metastasis Reviews (2021)

-

The hepatic pre-metastatic niche in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Molecular Cancer (2018)

-

Chemotherapy and tumor microenvironment of pancreatic cancer

Cancer Cell International (2017)

-

The prognostic value and pathobiological significance of Glasgow microenvironment score in gastric cancer

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2017)

-

Human pancreatic stellate cells modulate 3D collagen alignment to promote the migration of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells

Biomedical Microdevices (2016)