Abstract

Background:

Activation of wild-type p53 with the small molecule sirtuin inhibitor Tenovin-6 (Tnv-6) induces p53-dependent apoptosis in many malignant cells. In contrast, Tnv-6 reduces chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) cell viability with dysregulation of autophagy, without increasing p53-pathway activity.

Methods:

Here, we have investigated whether a quiescent phenotype (unique to CLL) determines the Tnv-6 response, by comparing the effects of Tnv-6 on activated and proliferating CLL. We further studied if these responses are p53-dependent.

Results:

Unlike quiescent cells, cell death in activated cultures treated with Tnv-6 was consistently associated with p53 upregulation. However, p53 acetylation remained unchanged, without caspase-3 cleavage or apoptosis on electron microscopy. Instead, cellular ultrastructure and protein profiles indicated autophagy inhibition, with reduced ubiquitin–proteasome activity. In specimens with mutant TP53 cultured with Tnv-6, changes in the autophagy-associated protein LC3 occurred independently of p53. Cells treated with Tnv-6 analogues lacking sirtuin inhibitory activity had attenuated LC3 lipidation compared with Tnv-6 (P⩽0.01), suggesting that autophagy dysregulation occurs predominantly through an effect on sirtuins.

Conclusion:

These cell cycle and p53-independent anti-leukaemic mechanisms potentially offer novel therapeutic approaches to target leukaemia-sustaining cells in CLL, including in disease with p53-pathway dysfunction. Whether targets in addition to sirtuins contribute to autophagy dysregulation by Tnv-6, requires further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Tenovin-6 (Tnv-6) is a small molecule that inhibits members of the sirtuin family of histone deacetylases (Lain et al, 2008). As non-histone proteins are also deacetylated by sirtuins, including the tumour suppressor p53, Tnv-6 is a non-genotoxic p53 activator. In cell lines derived from several solid organ malignancies, and chronic myeloid leukaemia, Tnv-6 increases levels of acetylated p53 and stimulates p53-dependent apoptosis (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012). These properties make Tnv-6 potentially relevant to the management of most patients with symptomatic chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), a disease in which p53 activity is a known determinant of outcomes after genotoxic chemotherapy (Pettitt et al, 2001; Rosenwald et al, 2004; Zenz et al, 2008). However, when the effects of Tnv-6 were studied in primary human CLL cells (MacCallum et al, 2013), unexpectedly, no consistent increase in the expression of p53 or proteins associated with the p53 pathway was detected, despite evidence for dose-dependent cytotoxicity. Further studies indicated that death in CLL cells was non-apoptotic and associated with the dysregulation of autophagy.

Reasons for the differences between the effects of Tnv-6 on CLL cells and other types of neoplasia (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012) require investigation. As the effects of sirtuin inhibitors can be tissue or context-specific (Cea et al, 2011), the autophagy-dysregulatory properties of Tnv-6 could be unique to CLL cells. In contrast to the highly proliferative cells examined in previous studies on Tnv-6 (Lain et al, 2008), CLL cells are relatively quiescent in culture. Although these non-dividing cells constitute the bulk of the leukaemic compartment in vivo, these have extensive proliferative histories (Lin et al, 2008). In addition, there is increasing evidence for the existence of sub-populations of cells with enhanced replicative potential that maintain the disease and are responsible for progression (Messmer et al, 2005; Calissano et al, 2009).

We hypothesised that the cell cycle and activation status of CLL cells may influence the effects of Tnv-6, with p53-dependent apoptosis being a feature of dividing cells and autophagy dysregulation being characteristic of non-cycling cells. Indeed, in CLL cells stimulated to divide in vitro, treatment with the sirtuin inhibitor nicotinamide has been shown to increase p53-pathway function and apoptotic cell death (Audrito et al, 2011). If these cellular responses were to be reproduced in studies with Tnv-6, then its cell cycle dependent effects would suggest the ability to target biologically heterogeneous leukaemic cell compartments through different mechanisms, as described with protein kinase inhibition (Natoni et al, 2011). In addition, the ability to demonstrate p53-dependent apoptosis would provide the rationale for the inclusion of Tnv-6 in therapeutic strategies for previously untreated patients with progressive CLL, most of whom have normal p53-pathway activity, but not in disease characterized by mutations in, or downstream of TP53 (Zenz et al, 2008; Lin et al, 2012).

In the present studies, we have analysed the responses of metabolically active and proliferating CLL cells to treatment with Tnv-6. In addition, we have investigated whether the cellular response to Tnv-6 is altered in the presence of TP53 dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Specimen selection

Blood specimen collection from consenting CLL patients was approved by the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics. All studies were performed following approval from Tayside Tissue Bank. Cells from a total of 21 patients (median age 70 years, range 58–86) were studied. Nine patients had received previous therapy, but no patient was on treatment at the time of blood collection. Enriched populations of CLL cells were isolated from blood as described previously (MacCallum et al, 2013). Prior to studies with Tnv-6, the integrity of p53 induction in these cells was confirmed in 24 h cultures with the genotoxic drug fludarabine (3 mM, Sigma, Dorset, UK).

CLL cell activation

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells were cultured at a final concentration of 2 × 106 cells ml−1 using 10% fetal calf serum in RPMI (culture medium) in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37 °C. To activate cells, cultures were treated with 100 units ml−1 interleukin-2 (IL-2, Novartis, Surrey, UK) and 1 μ M ml−1 CpG oligonucleotides (CpG ODN, DSP30, TIB MolBiol GmbH, Berlin, Germany) (Decker et al, 2000). Controls consisted of cells incubated in culture medium. Cells recovered at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h from IL-2/CpG ODN containing and control cultures were assayed for activation and proliferation, through morphological assessment, spectrophotometric measurement of intracellular ATP content and flow cytometric analysis of the expression of Ki-67 and DNA content using propidium iodide (PI) labelling (Supplementary Methods). The effects of Tnv-6 were then investigated by treating optimally activated cultures with 10 μ M Tnv-6 for a further 4 or 24 h.

Measurement of cell viability

Viability of CLL cells was studied by flow cytometric analysis of cells stained with 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (Tauro et al, 2002; Zembruski et al, 2012). Data from 10 000 cells was acquired on a FACScan (Becton-Dickinson, Oxford, UK) within 2 h of fixation and the proportion of live and dead cells was analysed using Cell Quest software (Becton-Dickinson).

Intracellular protein expression

Changes in intracellular proteins following culture with Tnv-6 were analysed by western blotting as described previously (MacCallum et al, 2013). The following antibodies were used during the study: DO-1 anti-p53 (1 : 1000) or polyclonal anti-p53 (1 : 3000, SAPU, Karluke, UK), p21waf1 (1 : 1000, Cell Signalling, Hertfordshire, UK), anti-p53 acetylated at Lysine position 320 (K-320), at K-373 (both 1 : 1000, Upstate Biotechnology, USA) or at K-382 (1 : 500, Bio-Legend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti- microtubule-associated proteins 1 A/1B light chain 3 A (LC3, 1 : 1000, Sigma), p62/Sequestosome 1 (1 : 5000, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-ubiquitin (1 : 2000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The protocol was modified slightly for the analysis of ubiquitinated proteins (Dayal et al, 2009). In brief, equal amounts of proteins for each sample were migrated in 4–12% SDS-PAGE in MES SDS Running Buffer (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. After washing in PBS, the membranes were boiled in deionized water for 30 min to expose ubiquitin epitopes before blocking and incubation with the primary anti-ubiquitin antibody.

To control for protein loading, each membrane was re-probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody to β-actin (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Changes in protein levels were quantified through densitometric analysis with ImageJ software.

Cellular ultrastructure

To study sub-cellular changes, 10 × 106 cells cultured with Tnv-6 for 4 h were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, processed and imaged using a JEOL 1200 EX transmission electron microscope.

Single-cell analysis for LC3 expression and TP53

In Tnv-6-treated cells from three patients with monoallelic loss of TP53, combined fluorescence-based assessment of the autophagy-associated protein LC3 and in situ hybridisation (FISH) for TP53 was undertaken to investigate changes in autophagy relative to TP53 status. In two patients, the burden of cells with TP53 loss exceeded 80% of the leukaemic cells. In the third patient, TP53 was deleted in 57% of cells. Mutational analysis by TP53 sequencing in two patients identified the missense mutations c.817C>A (exon 8, with resulting p.R273S) in one and c.613T>G (exon 6, causing p.Y205D) in the other, both associated with loss of p53 transcriptional activity (International Agency for Research in Cancer, TP53 Database, http://p53.iarc.fr).

For combined single-cell analysis, cells from cultures with or without Tnv-6 were fixed, permeabilised and stained with anti-LC3 (1:500, MBL, St Woods Hole, MA, USA) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Life Technologies). Slides were then stained with DAPI II (Abbot Molecular, Berkshire, UK) to enable localisation of nuclei and viewed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescence microscope. Fluorescence from LC3 puncta from a total of 50 cells was captured using an Olympus BX61 (Hamburg, Germany) fluorescence microscope with X-Cite fluorescence system and CytoVision software to create Z-stacked images. Following image capture, slides were washed before being permeabilised in sodium thiocyanate (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA) at 80 °C for 15 min. Following further washes in distilled water and sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.0), slides were treated with protease solution (Abbott) for 10 min at 37 °C after which in situ hybridisation with the CEP17/TP53 (17p13.1) (Abbott) probes was performed as described previously (Groves et al, 2012). Fluorescence was captured from cells in the same microscopy field-settings as for LC3 determination, enabling simultaneous analysis of LC3 fluorescence and TP53 signals in 50 individual cells. The difference in the mean corrected total cell fluorescence between Tnv-6-treated and control cultures was compared using ImageJ analysis.

Cellular response to Tnv-6 analogues

To investigate whether the effects of Tnv-6 in CLL cells are mediated through the targeted inhibition of sirtuins (Lain et al, 2008), activated cultures were treated with structural analogues that have reduced activity against recombinant human SirT1 and SirT2. Several reports on the preparation and characterisation of Tnv-6 analogues have been reported to date (Lain et al, 2008; McCarthy et al, 2012). Tenovins-30q and −37 were prepared as described previously in the literature (McCarthy et al, 2012; Pirrie et al, 2012) whereas the novel analogue Tenovin-45 was prepared as described in the Supplementary Material. All three analogues lack activity against SirT1 and SirT2 in vitro, but their water solubility and ability to cross biological membranes are likely to be the same as Tnv-6. Changes in p53 and LC3 expression in optimally activated CLL cells were examined after 4 h of culture with 10 μM of each analogue and compared with Tnv-6.

Statistical analysis

The arithmetic mean was used to measure the central tendency of data. The dispersion of values around the mean was expressed as the standard deviation (s.d.) in analysis of raw data, or as standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) when mean values were being compared. The significance of difference between the means of untreated control and corresponding Tnv-6-treated cells was tested using the paired Student’s t-test. All P-values were two-tailed and statistical significance was set at the level of P<0.05.

Results

p53 pathway function is intact in CLL specimens

Presence of intact p53-pathway function in CLL cells was confirmed by quantifying changes in intracellular p53 in cells treated with the genotoxic drug fludarabine. After 24 h, increased expression of p53 was detected in cells from all patients compared with untreated cultures (Supplementary Figure S1). By densitometric quantification, a mean 2.0-fold increase in p53 induction was present (range: 1.3–3.2; P=0.0038). In addition, it was possible to identify cleaved caspase-3 in all treated specimens (Supplementary Figure S1), indicating the integrity of p53-pathway function and the suitability of the specimens for analysis of p53 responses to Tnv-6.

IL-2/CpG ODN optimally activates CLL cells between 36 and 48 h

In replicate cultures from each specimen (n=9), changes in cellular morphology, ATP levels, Ki-67 expression and DNA content following culture in IL-2/CpG ODN for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h identified the period of optimal CLL cell activation as being between 36 and 48 h (Supplementary Table S1). To study the effects of Tnv-6, cultures activated with IL-2/CpG ODN for 42 h were incubated for a further 4 h (total culture time of 46 h) or 24 h (total culture time of 66 h) with 10 μM Tnv-6. Cell responses were compared with those of quiescent cells cultured in growth medium for 42 h followed by incubation with Tnv-6 (10 μ M) for an additional 4 or 24 h.

Effects of Tnv-6 on CLL cells

Tnv-6 causes equivalent cytotoxicity in activated and quiescent cultures

Cellular viability following incubation with Tnv-6 was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of 7-AAD-stained cells from nine sets of quiescent and activated cultures. Levels of cell death varied amongst control and Tnv-6 containing cultures at 24 and 4 h, indicating the biological heterogeneity of CLL. Analysis of raw data using the Student’s t-test for paired samples indicated a higher proportion of 7-AADint/high (non-viable) cells in the presence of Tnv-6 in quiescent cultures at 24 (P=0.0008) and 4 h (P=0.0025), as well as in activated cultures at these time-points (P=0.0002 and 0.017, respectively). These differences are illustrated in Figure 1; for simplicity of presentation, the mean result from Tnv-6-treated cultures has been normalised to the mean for controls. A representative FACS profile of 7-AAD labelling without (control) and in the presence of Tnv-6 is shown in Supplementary Figure S2A–D.

Cytotoxicity of Tnv-6 to quiescent and activated CLL cells. The proportion of 7-AADint/high cells in cultures was used to measure cytotoxicity with Tnv-6 and expressed relative to untreated control cultures. Significant levels of cytotoxicity were observed with Tnv-6 at both 4 and 24 h in cultures conditions favouring quiescence as well as activation.

Tnv-6 increases p53 without induction of apoptosis

Changes in intracellular proteins in CLL cells following Tnv-6 treatment were investigated in 4 h cultures (Figure 2). Treatment of activated cultures with Tnv-6 associated with consistent increases in p53 expression. The mean increase of 11-fold (range 5–23, P=0.0007, n=9) contrasted with the lack of significant p53 expression observed under culture conditions where CLL cells are quiescent. In addition, there was a 1.4±0.23-fold increase in expression of p21waf1 (P=0.005). The functional consequences of p53 induction for apoptosis in activated cells were investigated further through an analysis of changes in caspase-3 (Fuchs et al, 1997). However, there was no increase in cleaved caspase-3 in either quiescent or activated cells despite elevated levels of p53 (Figure 2). Furthermore, p53 acetylation at Lysine residues 320, 373 or 382 (targeted by sirtuins) (Knights et al, 2006) remained unchanged (Supplementary Figure S3), despite the increases in total p53.

p53 expression in activated CLL cells treated with Tnv-6. Representative western blot gel images demonstrate increased p53 in cells from Tnv-6-treated activated CLL cultures (Tnv-6) compared with untreated cultures and quiescent cultures without (untreated) or with Tnv-6 (A). However, total caspase-3 (CP-3) remained unchanged with no detectable cleaved caspase-3 (CCP-3) in cells from cultures with Tnv-6. The validity of the assay is confirmed by the detection of CCP-3 in the positive control consisting of protein from CLL cells cultured with fludarabine. An increase in p21waf1 expression also occurred following Tnv-6 treatment of activated cells (right lane in B) compared to cells from control cultures (left lane in B); however, the overall magnitude of the change compared with controls (1.4-fold; P=0.005) was lower than the 11-fold increase (P=0.0007) observed with p53 (C).

Tnv-6 inhibits autophagy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), performed to clarify the mode of cell death following Tnv-6 treatment, showed no ultrastructural cellular changes to suggest apoptosis (Taatjes et al, 2008) (n=3). Instead, an alteration in autophagosomes was evident from the increase in intracytoplasmic double-membraned vacuoles containing cytoplasmic components (Figure 3). Number of autophagosomes per cell (from a total count of 50 cell sections per culture) were 12-fold higher (range 9–18) at 4 h in Tnv-6 containing activated cultures than in corresponding untreated controls (P=0.01). Similarly, and consistent with our previous results (MacCallum et al, 2013), a significant increase in autophagosome numbers was also observed in cells from quiescent cultures treated with Tnv-6, but the magnitude of the change was less than in activated cells (data not shown).

Changes in cellular ultrastructure following Tnv-6 treatment of activated CLL cells. The representative TEM images (× 10K magnification) from one (out of 3) CLL specimens analysed by transmission electron microscopy shows sub-cellular differences between cells cultured without (A) or in the presence of Tnv-6 (B). To visualize these differences in greater detail, images at higher magnification (× 30K) are shown of a cell each from control cultures (C) and Tnv-6 containing cultures (D). The cell cultured with Tnv-6 (highlighted by the black arrow in (B)) contains double-membrane bound cytoplasmic vacuoles (interrupted black arrow) and larger vacuoles with cytoplasmic contents (continuous black arrow) suggestive of early and late autophagosomes respectively (D). The mean numbers of autophagosomes per cell in 50 cell sections per culture (n=3) was 12-fold higher (range 9–18) with Tnv-6 than controls not cultured with Tnv-6 (P=0.01) (E).

The dysregulation of autophagy was further investigated in protein expression studies. The expression profile of the autophagy-associated proteins LC3 and p62 in quiescent cells treated with Tnv-6 was identical to that described previously (MacCallum et al, 2013), and therefore, only results with activated cells will be described hereafter. Culture with Tnv-6 resulted in a mean 2.7-fold (range 1.8–4.2) increase in the lipidated form of LC3 (LC3 II) (P=0.0003, n=9, Figure 4). Together, the TEM features and accumulation of lipidated LC3 indicated a change in autophagy in Tnv-6-treated CLL cells. As similar increases in autophagosomes can occur during autophagy induction (Hussain et al, 2008) or inhibition (Barth et al, 2010; Klionsky et al, 2012), further studies were undertaken to characterise the nature of autophagy dysregulation with Tnv-6.

Changes in autophagy-associated protein expression following Tnv-6 treatment of activated CLL cells. Following Tnv-6 treatment, a mean 2.7-fold increase in lipidated LC3 (LC3 II) was observed in activated CLL cells by densitometric analysis (P=0.0003) (A). In addition, the representative western blot image (B) shows accumulation of p62/Sequestosome 1 in the presence of Tnv-6 suggesting inhibition of autophagy. The concurrent analysis of protein from cells treated with the autophagy-inducer Ku-0063794 (Ku) in this panel (B) demonstrates the expected reduction in p62 to validate the assay. In C, the western blot image demonstrates changes in autophagy-flux in CLL cells from one (of two patients) patient with single-agent or combination treatment with Tnv-6, Bafilomycin-A1 (Baf-1) and Ku. There is absence of a synergistic increase in lipidated LC3 (LC3 II) in cells simultaneously treated with Baf-1 and Tnv-6 (unlike that observed with Baf-1 and Ku), confirming the inhibition of autophagy-flux by Tnv-6.

The expression of p62/Sequestosome 1, an adaptor protein that regulates the clearance of select ubiquitinated substrates (Korolchuk et al, 2009) was studied, as it accumulates during the inhibition of autophagy (Bjørkøy et al, 2005). A significant increase in p62/Sequestosome 1 (sixfold, range 2–12, P=0.003) was detected in cells from Tnv-6-treated cultures suggesting the inhibition of autophagy in the presence of Tnv-6 (Figure 4B). However, p62/Sequestosome 1 increases can also associate with the induction of autophagy (Klionsky et al, 2012), and therefore, further studies through the concomitant use of agents that stimulate or block autophagy were undertaken in two specimens, to characterise the autophagy-flux in Tnv-6-treated cells (MacCallum et al, 2013). Lysosomal degradation was blocked by treating cultures with 10nM bafilomycin-A1 (that targets vacuolar-type H+-ATPase), such that stimulation of autophagy following Tnv-6 treatment would result in a synergistic accumulation of LC3 II. However, although an increase in LC3 II expression was evident with bafilomycin-A1 compared with untreated cells, this change was similar to the LC3 II increase in Tnv-6-treated cells, and the addition of bafilomycin-A1 to Tnv-6 cultures caused no further increase in LC3 II (Figure 4C). This was in contrast to combining bafilomycin-A1 with the mTOR inhibitor Ku-0063794 (4 μ M) (García-Martínez et al, 2009), known to induce autophagy. These studies thus indicate a role for Tnv-6 in inhibiting the later stages of autophagy in activated CLL cells.

Tnv-6 delays ubiquitin–proteasome signalling

As the inhibition of autophagy associates with the delayed clearance of substrates through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Korolchuk et al, 2009), we hypothesised that Tnv-6 treatment of CLL cells could affect ubiquitin–proteasome function and cause the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, including p53, that undergo physiological degradation through this pathway. By western blotting of total protein lysates from activated cultures, heterogeneity in the levels of ubiquitinated proteins was detected in cells from different patients; following treatment with Tnv-6, the levels of ubiquitinated substrates in cells (standardised to actins) increased to a mean of 21.9±4.2 arbitrary units (a.u.) from 18.7±5.4 a.u. in control cultures (P=0.049, n=6, Figure 5). However, no increase in the amount of ubiquitinated p53 was detected in cells recovered from Tnv-6-treated cultures (data not shown).

Changes in ubiquitin–proteasome pathway activity following Tnv-6-treatement of activated CLL cells. (A) Western blot images from three patient specimens (1, 2 and 3) cultured with Tnv-6 show an increase in ubiquitinated substrates (Ub-sub) compared with corresponding controls (Cntrl). Protein extracts from A375 melanoma cells cultured without (−) or in the presence (+) of the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib were used as controls. A corresponding decrease in ubiquitinated nucleosomal histone H2A (Ub-H2A) (described with proteasome inhibitors in tumour cells, Mimnaugh et al, 1997) is also evident in the presence of Tnv-6. There is no difference in free ubiquitin (Ub) between cells from Tnv-6-treated and Cntrl cultures. Despite heterogeneity in responses, Tnv-6-treated CLL cells showed accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins (expressed in arbitrary units, a.u. after standardisation to β-actin) compared with corresponding untreated controls (B).

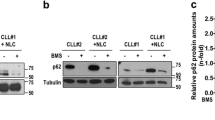

Tnv-6 dysregulates autophagy independently of p53

Whether the increase in p53 in response to Tnv-6 is functionally relevant to the dysregulation of autophagy was investigated in cells from three patients with monoallelic deletions of TP53. As shown in Figure 6, the protein expression profiles indicate the presence of mutant non-functional protein in two patients, suggesting the existence of a type-A p53 pathway defect in these cells (Pettitt et al, 2001). Following culture with Tnv-6, no change in p53 expression was evident in specimens from patients 1 and 2 (Figure 6). Although a slight increase in p53 levels was observed in cells from patient 3, overall, the differences were not statistically significant. An increase in p21waf1 expression was also observed (Figure 6), but unlike Tnv-6-treated cells with intact p53 pathway activity described previously, the mean increase in p21waf1 (1.8-fold, range 1.7–2.3) in TP53 mutant CLL was not statistically significant compared with controls (P=0.18).

Protein expression in activated TP53 -deleted CLL cells cultured with Tnv-6. Basal p53 expression profiles in patients 1 and 3 with TP53 mutant clones comprising 86 and 57% of cells suggest a type-A p53-pathway defect. The TP53 gene in patient 2 was not sequenced, but the complete absence of p53 makes a nonsense mutation likely. Following Tnv-6 treatment, there is no change in p53 expression in patients 1 and 2, although levels increase over basal levels in patient 3, probably reflecting changes in cells without TP53 loss. There is a slight increase in the expression of p21waf1 in each specimen treated with Tnv-6 compared with untreated controls. Despite the presence of TP53 deletions, there is significant accumulation of lipidated LC3.

When the expression of lipidated LC3 (LC3 II) was compared by western blotting, increased levels were noted in cells cultured with Tnv-6 compared with controls (Figure 6), P=0.04, n=3. By fluorescence microscopic analysis of single cells stained for LC3 and del(17p) (Figure 7), an increase in LC3 ‘puncta’ was observed in cells from all three specimens cultured with Tnv-6, indicating altered autophagy despite TP53 loss. In 50 cells with monoallelic TP53 loss per specimen, the mean corrected total cellular fluorescence for LC3 was twofold higher (range 1.5–3.0) in cells from Tnv-6 containing activated cultures than corresponding control cultures (Figure 7), n=3, P=0.04.

Dysregulation of autophagy by Tnv-6 in activated CLL cells with monoallelic loss of TP53. Basal LC3 expression by immunofluorescence (green signals) in untreated (control) cells (A). FISH staining for TP53 (red signal) and the chromosome enumeration probe, CEP for chromosome 17 (green signal) identifies cells with monoallelic deletion of TP53 (hence one red signal) in this field (B). Following Tnv-6 treatment, LC3 puncta are increased (C) in these cells, evident in the FISH image for TP53 and CEP17 corresponding to the same field (D). The graphical representation of results following analysis of two additional specimens indicates the mean corrected cellular LC3 fluorescence to be significantly increased in TP53-deleted cells cultured with Tnv-6, indicating p53-independent autophagy dysregulation (E).

Effects of Tnv-6 analogues on p53 and autophagy

As the cellular response to Tnv-6 in our studies contrasts with the results reported in other neoplastic cells treated with Tnv-6 (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012), we investigated whether autophagy dysregulation in CLL occurs potentially through alternative targets of this sirtuin inhibitor. The ability of three Tnv-6 analogues lacking in vitro activity against SirT1 and SirT2, to alter p53 expression and LC3 lipidation in cells from six activated cultures was compared with Tnv-6. The structures and a comparison of the biological activity and physical properties of the analogues used are described in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S4. By visual examination, no increases in p53 or LC3 lipidation were evident in CLL cells treated with Tnv-6 analogues compared with Tnv-6 (Figure 8A and B). To control for potential differences in protein loading, quantitative densitometry of p53 and LC3 II expression compared with β-actin was undertaken and confirmed the difference in expression levels between cells treated with Tnv-6 and its analogues (P⩽0.01 (p53) and P<0.0004 (LC3 II)). These results suggest that the Tnv-6 effects were related to sirtuin inhibition. However, densitometric analysis also indicated that LC3 II expression with Tnv-6 analogues was slightly higher in the presence of Tnv-45 (P=0.015) and Tnv-37 (P=0.012) than in untreated control cells (Figure 8C). Comparison of the LC3 II response to Tnv-6, with that observed in cultures with the analogues (Figure 8C) suggests that ⩾90% of the Tnv-6 effect occurs through structural moieties required to inhibit sirtuins. We also observed that the expression intensities of LC3 II and p53 correlated strongly in cells treated with Tnv-6 or its analogues (r=0.79; P<0.0001, Figure 8D).

Changes in p53 and LC3 expression following treatment of activated CLL cells with Tnv-6 analogues. Panels A and B show protein expression from two patient specimens, each cultured with Tnv-6 and analogues (Tnv-45, Tnv-30q and Tnv-37) compared with untreated control (Cntrl) cultures. The increase in p53 and lipidated LC3 (LC3 II) seen in cells in culture with Tnv-6 is significantly attenuated in the presence of the analogues (B). However, by densitometric quantification of LC3 II expression standardised to β-actin, Tnv-45 and -37 retain slight, but significant ability to upregulate LC3 II expression compared with Cntrl cultures (C). Overall, a strong positive correlation existed between the expression intensities of LC3 II and p53 in CLL cells treated with Tnv-6 or analogues (D).

Discussion

Previously, in quiescent CLL cells with intact genotoxic p53 responses treated with Tnv-6, we identified the preferential dysregulation of autophagy, in the absence of p53 activity (MacCallum et al, 2013). As these observations were at variance with the p53-dependent apoptotic effects of Tnv-6 in other malignancies (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012), here we have investigated whether the biological responses to Tnv-6 in CLL are unique to the disease, consequent to the quiescent cellular phenotype, and are p53-independent. Through the analysis of changes in cellular ultrastructure and protein expression, we have been able to demonstrate that the cytotoxic effects of Tnv-6 in CLL cells associates with the inhibition of autophagy even in conditions that favour cellular activation and proliferation. As Tnv-6 is non-toxic to normal haemopoietic cells (Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012; MacCallum et al, 2013), the cell cycle-independent dysregulation of autophagy in CLL suggests its clinical potential to effectively target leukaemic sub-populations, including disease-sustaining cells with proliferative capability.

As with quiescent cells, death is not associated with apoptosis. 7-AAD-based flow cytometry was used to measure cytotoxicity with Tnv-6, as the dye permeates cells with loss of membrane integrity during cell death. Despite its frequent use as an assay to quantify ‘apoptosis’ (Zembruski et al, 2012), 7-AAD labelling does not specify apoptosis (Fujisawa et al, 2007) and therefore electron microscopy, considered the ‘gold standard’ for detecting apoptosis (Taatjes et al, 2008) was used to confirm the absence of ultrastructural changes indicative of apoptotic death. The absence of apoptotic cell death was surprising, as a striking increase in p53 was identified following Tnv-6 treatment in all activated CLL cultures. This p53 response contrasted with that in quiescent cells here, and in previous studies (MacCallum et al, 2013), where no increase in p53 expression is detected. The activation and proliferation status of CLL cells thus appears to be a key determinant of the Tnv-6-associated increment in p53.

The increase in p53 expression in activated cells is concordant with that observed in other neoplastic cell types treated with Tnv-6 (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012). However, unlike other malignancies, there is no p53 pathway-dependent apoptotic signalling in CLL cells, as the expected downstream effect on caspase-3 (Audrito et al, 2011) was not observed and ultrastructural features of apoptosis (to suggest alternative pro-apoptotic mechanisms) are absent. That the p53, despite its increase, is non-functional is suggested by the lack of an increase in p53-activating acetylation at commonly modified Lysine residues (Knights et al, 2006). In particular, there was absence of acetylation at residue 320, which is known to preferentially promote cell cycle arrest over apoptotic death (Cheng et al, 2003), and could have clarified reasons for the absence of apoptosis in our experiments. To rationalise the discrepancy between p53 expression and activity, we examined the possibility that the rise in cellular p53 levels in Tnv-6-treated cells occurs due to ubiquitin–proteasome (UP) pathway dysfunction during autophagy inhibition. The delayed degradation of UP-dependent client proteins (that include p53) is known to occur during inhibition of autophagy through the accumulation of p62/Sequestosome 1 (Korolchuk et al, 2009). As rapid increases in p62/Sequestosome 1 were detected following Tnv-6 treatment, we expected to detect a coincident increase in ubiquitinated proteins and therefore, non-functional p53. In support of our hypothesis, an increase in ubiquitinated proteins was seen in Tnv-6-treated CLL cells, confirming delayed UP-transit. However, no change in ubiquitinated p53 was detected, suggesting the complexity of p53 regulation in CLL cells treated with Tnv-6.

We therefore decided to clarify whether p53-pathway activity is important for autophagy dysregulation (Kenzelmann Broz et al, 2013; Napoli and Flores, 2013) by analysing LC3 responses to Tnv-6 in cells with deletions of TP53, a critical determinant of impaired p53-pathway responses (Zenz et al, 2008; Mohr et al, 2011). Dysfunction in p53-dependent responses in these cells was indicated by the ‘loss of function’ mutations identified through sequencing of the retained TP53 allele and the high basal level of p53 protein expression in two specimens (Pettitt et al, 2001). Although CLL patients with a TP53 mutant clone size of >20% are classed as ‘TP53 mutant CLL’ (Catovsky et al, 2007), here, by selecting specimens with a higher burden of TP53-deleted clones (86%, 83% and 57%, respectively) we were able to avoid the potentially confounding effects of protein expression from sub-clones with wild-type TP53 (Mohr et al, 2011) and demonstrate the accumulation of LC3 II following Tnv-6 treatment.

In addition, we undertook more definitive analysis of single cells, by combining FISH and immunofluorescence studies to demonstrate the alteration of LC3 expression in cells with monoallelic TP53 deletions and mutant TP53, confirming the redundancy of p53-dependent signalling in the dysregulation of autophagy. Despite p53-pathway dysfunction in these cells, there was a non-significant increase in p21waf1 expression. It is likely that this change in p21waf1, described earlier in cells with intact p53 responses to DNA damage, and at the transcriptional level (MacCallum et al, 2013) occurs independently of p53, similar to mechanisms in breast cancer cells with p53 dysfunction (McCarthy et al, 2013). Arguably, p53-dependent regulation of p21waf1 expression in the TP53 mutant cases studies here could occur in leukaemic cells without TP53 loss (14%, 17% and 43%, respectively), but we have no evidence that the increase in total p53 following Tnv-6 treatment associates with enhanced p53-pathway function, making the increase in p21waf1 a likely p53-independent effect. Further studies on sub-populations of CLL cells (based on TP53 status) would help confirm this hypothesis, but the loss of cell viability during separation of clones will preclude further functional studies.

The p53-independent anti-leukaemic mechanisms of Tnv-6 identified through our studies could be particularly relevant to CLL patients with sub-types of p53-pathway dysfunction associated with poor outcomes to current therapy (Lin et al, 2012). Whether these mechanisms, seemingly unique to CLL cells, are initiated through sirtuin inhibition, or represent off-target effects of Tnv-6 was investigated. Cell-transfection studies (as those performed previously (Lain et al, 2008; Sunami et al, 2013) towards identifying Tnv-6 targets are challenging in CLL due to the fragile nature of these cells, and therefore the effects of Tnv-6 analogues (lacking the capacity to inhibit SirT1 and SirT2) on LC3 responses were studied here. The fact that over 90% of the Tnv-6 effect on LC3 II was reduced with the use of analogues suggests that the effects of Tnv-6 in CLL occur predominantly through sirtuin inhibition. However, LC3 lipidation was not completely abolished in the presence of the analogues. These results could reflect residual anti-SirT1/SirT2 activity of Tnv-6 analogues in vivo or the effects of Tnv-6 on an alternative cellular target. The residual, attenuated LC3 II response with the analogues also provided an opportunity to investigate a possible association between the expression of lipidated LC3 II and p53. Based on the strength of correlation between the expression of these proteins, and the redundancy of p53 networks in lipidation of LC3, we suggest that the accumulation of non-functional p53 in Tnv-6-treated cells reflects the magnitude of autophagy inhibition.

It would be of interest to investigate whether the changes in autophagy parallel p53-dependent signalling in ‘non-CLL’ cells treated with Tnv-6 (Lain et al, 2008; Yuan et al, 2012), with possible differences in the Tnv-6 target or autophagy-flux resulting in an apoptotic cellular response. An evaluation of the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis in neoplastic cells studied previously (Lain et al, 2008; Li et al, 2012; Yuan et al, 2012) is required before the Tnv-6- effect in CLL can be considered to be tissue-specific. Our observations on mechanisms associated with the cytotoxicity of Tnv-6 in proliferating and TP53 mutant CLL could then find wider application in cancer therapeutics.

Change history

29 October 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Audrito V, Vaisitti T, Rossi D, Gottardi D, D'Arena G, Laurenti L, Gaidano G, Malavasi F, Deaglio S (2011) Nicotinamide blocks proliferation and induces apoptosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells through activation of the p53/miR-34a/SIRT1 tumor suppressor network. Cancer Res 71: 4473–4483.

Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF (2010) Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J Pathol 221: 117–124.

Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T (2005) p62/SQSTM1 forms protein aggregates degraded by autophagy and has a protective effect on huntingtin-induced cell death. J Cell Biol 171: 603–614.

Calissano C, Damle RN, Hayes G, Murphy EJ, Hellerstein MK, Moreno C, Sison C, Kaufman MS, Kolitz JE, Allen SL, Rai KR, Chiorazzi N (2009) In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 114: 4832–4842.

Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, Oscier D, Dyer MJ, Bezares RF, Pettitt AR, Hamblin T, Milligan DW, Child JA, Hamilton MS, Dearden CE, Smith AG, Bosanquet AG, Davis Z, Brito-Babapulle V, Else M, Wade R, Hillmen P (2007) Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370: 230–239.

Cea M, Soncini D, Fruscione F, Raffaghello L, Garuti A, Emionite L, Moran E, Magnone M, Zoppoli G, Reverberi D, Caffa I, Salis A, Cagnetta A, Bergamaschi M, Casciaro S, Pierri I, Damonte G, Ansaldi F, Gobbi M, Pistoia V, Ballestrero A, Patrone F, Bruzzone S, Nencioni A (2011) Synergistic interactions between HDAC and sirtuin inhibitors in human leukemia cells. PLoS One 6: e22739.

Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF (2003) Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10794–10799.

Dayal S, Sparks A, Jacob J, Allende-Vega N, Lane DP, Saville MK (2009) Suppression of the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 causes the accumulation of unanchored polyubiquitin and the activation of p53. J Biol Chem 284: 5030–5041.

Decker T, Schneller F, Sparwasser T, Tretter T, Lipford GB, Wagner H, Peschel C (2000) Immunostimulatory CpG-oligonucleotides cause proliferation, cytokine production, and an immunogenic phenotype in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood 95: 999–1006.

Fuchs EJ, McKenna KA, Bedi A (1997) p53-dependent DNA damage-induced apoptosis requires Fas/APO-1-independent activation of CPP32beta. Cancer Res 57: 2550–2554.

Fujisawa A, Kambe N, Saito M, Nishikomori R, Tanizaki H, Kanazawa N, Adachi S, Heike T, Sagara J, Suda T, Nakahata T, Miyachi Y (2007) Disease-associated mutations in CIAS1 induce cathepsin B-dependent rapid cell death of human THP-1 monocytic cells. Blood 109: 2903–2911.

García-Martínez JM, Moran J, Clarke RG, Gray A, Cosulich SC, Chresta CM, Alessi DR (2009) Ku-0063794 is a specific inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Biochem J 421: 29–42.

Groves MJ, Maccallum SF, Boylan MT, Haydock S, Cunningham J, Gelly K, Gowans D, Kerr R, Coates PJ, Tauro S (2012) Heterogeneity of p53-pathway Protein Expression in Chemosensitive Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Pilot Study. J Cancer 3: 354–361.

Hussain SR, Lucas DM, Johnson AJ, Lin TS, Bakaletz AP, Dang VX, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Ruppert AS, Byrd JC, Kuppusamy P, Crouser ED, Grever MR (2008) Flavopiridol causes early mitochondrial damage in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells with impaired oxygen consumption and mobilization of intracellular calcium. Blood 111: 3190–3199.

Kenzelmann Broz D, Spano Mello S, Bieging KT, Jiang D, Dusek RL, Brady CA, Sidow A, Attardi LD (2013) Global genomic profiling reveals an extensive p53-regulated autophagy program contributing to key p53 responses. Genes Dev 27: 1016–1031.

Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Ahn HJ, Ait-Mohamed O, Ait-Si-Ali S, Akematsu T, Akira S, Al-Younes HM, Al-Zeer MA, Albert ML, Albin RL, Alegre-Abarrategui J, Aleo MF, Alirezaei M, Almasan A, Almonte-Becerril M, Amano A, Amaravadi R, Amarnath S, Amer AO, Andrieu-Abadie N, Anantharam V, Ann DK, Anoopkumar-Dukie S, Aoki H, Apostolova N, Arancia G, Aris JP, Asanuma K, Asare NY, Ashida H, Askanas V, Askew DS, Auberger P, Baba M, Backues SK, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Bai XY, Bailly Y, Baiocchi R, Baldini G, Balduini W, Ballabio A, Bamber BA, Bampton ET, Bánhegyi G, Bartholomew CR, Bassham DC, Bast RC Jr, Batoko H, Bay BH, Beau I, Béchet DM, Begley TJ, Behl C, Behrends C, Bekri S, Bellaire B, Bendall LJ, Benetti L, Berliocchi L, Bernardi H, Bernassola F, Besteiro S, Bhatia-Kissova I, Bi X, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Blum JS, Boise LH, Bonaldo P, Boone DL, Bornhauser BC, Bortoluci KR, Bossis I, Bost F, Bourquin JP, Boya P, Boyer-Guittaut M, Bozhkov PV, Brady NR, Brancolini C, Brech A, Brenman JE, Brennand A, Bresnick EH, Brest P, Bridges D, Bristol ML, Brookes PS, Brown EJ, Brumell JH, Brunetti-Pierri N, Brunk UT, Bulman DE, Bultman SJ, Bultynck G, Burbulla LF, Bursch W, Butchar JP, Buzgariu W, Bydlowski SP, Cadwell K, Cahová M, Cai D, Cai J, Cai Q, Calabretta B, Calvo-Garrido J, Camougrand N, Campanella M, Campos-Salinas J, Candi E, Cao L, Caplan AB, Carding SR, Cardoso SM, Carew JS, Carlin CR, Carmignac V, Carneiro LA, Carra S, Caruso RA, Casari G, Casas C, Castino R, Cebollero E, Cecconi F, Celli J, Chaachouay H, Chae HJ, Chai CY, Chan DC, Chan EY, Chang RC, Che CM, Chen CC, Chen GC, Chen GQ, Chen M, Chen Q, Chen SS, Chen W, Chen X, Chen X, Chen X, Chen YG, Chen Y, Chen Y, Chen YJ, Chen Z, Cheng A, Cheng CH, Cheng Y, Cheong H, Cheong JH, Cherry S, Chess-Williams R, Cheung ZH, Chevet E, Chiang HL, Chiarelli R, Chiba T, Chin LS, Chiou SH, Chisari FV, Cho CH, Cho DH, Choi AM, Choi D, Choi KS, Choi ME, Chouaib S, Choubey D, Choubey V, Chu CT, Chuang TH, Chueh SH, Chun T, Chwae YJ, Chye ML, Ciarcia R, Ciriolo MR, Clague MJ, Clark RS, Clarke PG, Clarke R, Codogno P, Coller HA, Colombo MI, Comincini S, Condello M, Condorelli F, Cookson MR, Coombs GH, Coppens I, Corbalan R, Cossart P, Costelli P, Costes S, Coto-Montes A, Couve E, Coxon FP, Cregg JM, Crespo JL, Cronjé MJ, Cuervo AM, Cullen JJ, Czaja MJ, D’Amelio M, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Davids LM, Davies FE, De Felici M, de Groot JF, de Haan CA, De Martino L, De Milito A, De Tata V, Debnath J, Degterev A, Dehay B, Delbridge LM, Demarchi F, Deng YZ, Dengjel J, Dent P, Denton D, Deretic V, Desai SD, Devenish RJ, Di Gioacchino M, Di Paolo G, Di Pietro C, Díaz-Araya G, Díaz-Laviada I, Diaz-Meco MT, Diaz-Nido J, Dikic I, Dinesh-Kumar SP, Ding WX, Distelhorst CW, Diwan A, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Dokudovskaya S, Dong Z, Dorsey FC, Dosenko V, Dowling JJ, Doxsey S, Dreux M, Drew ME, Duan Q, Duchosal MA, Duff K, Dugail I, Durbeej M, Duszenko M, Edelstein CL, Edinger AL, Egea G, Eichinger L, Eissa NT, Ekmekcioglu S, El-Deiry WS, Elazar Z, Elgendy M, Ellerby LM, Eng KE, Engelbrecht AM, Engelender S, Erenpreisa J, Escalante R, Esclatine A, Eskelinen EL, Espert L, Espina V, Fan H, Fan J, Fan QW, Fan Z, Fang S, Fang Y, Fanto M, Fanzani A, Farkas T, Farré JC, Faure M, Fechheimer M, Feng CG, Feng J, Feng Q, Feng Y, Fésüs L, Feuer R, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Fimia GM, Fingar DC, Finkbeiner S, Finkel T, Finley KD, Fiorito F, Fisher EA, Fisher PB, Flajolet M, Florez-McClure ML, Florio S, Fon EA, Fornai F, Fortunato F, Fotedar R, Fowler DH, Fox HS, Franco R, Frankel LB, Fransen M, Fuentes JM, Fueyo J, Fujii J, Fujisaki K, Fujita E, Fukuda M, Furukawa RH, Gaestel M, Gailly P, Gajewska M, Galliot B, Galy V, Ganesh S, Ganetzky B, Ganley IG, Gao FB, Gao GF, Gao J, Garcia L, Garcia-Manero G, Garcia-Marcos M, Garmyn M, Gartel AL, Gatti E, Gautel M, Gawriluk TR, Gegg ME, Geng J, Germain M, Gestwicki JE, Gewirtz DA, Ghavami S, Ghosh P, Giammarioli AM, Giatromanolaki AN, Gibson SB, Gilkerson RW, Ginger ML, Ginsberg HN, Golab J, Goligorsky MS, Golstein P, Gomez-Manzano C, Goncu E, Gongora C, Gonzalez CD, Gonzalez R, González-Estévez C, González-Polo RA, Gonzalez-Rey E, Gorbunov NV, Gorski S, Goruppi S, Gottlieb RA, Gozuacik D, Granato GE, Grant GD, Green KN, Gregorc A, Gros F, Grose C, Grunt TW, Gual P, Guan JL, Guan KL, Guichard SM, Gukovskaya AS, Gukovsky I, Gunst J, Gustafsson AB, Halayko AJ, Hale AN, Halonen SK, Hamasaki M, Han F, Han T, Hancock MK, Hansen M, Harada H, Harada M, Hardt SE, Harper JW, Harris AL, Harris J, Harris SD, Hashimoto M, Haspel JA, Hayashi S, Hazelhurst LA, He C, He YW, Hébert MJ, Heidenreich KA, Helfrich MH, Helgason GV, Henske EP, Herman B, Herman PK, Hetz C, Hilfiker S, Hill JA, Hocking LJ, Hofman P, Hofmann TG, Höhfeld J, Holyoake TL, Hong MH, Hood DA, Hotamisligil GS, Houwerzijl EJ, Høyer-Hansen M, Hu B, Hu CA, Hu HM, Hua Y, Huang C, Huang J, Huang S, Huang WP, Huber TB, Huh WK, Hung TH, Hupp TR, Hur GM, Hurley JB, Hussain SN, Hussey PJ, Hwang JJ, Hwang S, Ichihara A, Ilkhanizadeh S, Inoki K, Into T, Iovane V, Iovanna JL, Ip NY, Isaka Y, Ishida H, Isidoro C, Isobe K, Iwasaki A, Izquierdo M, Izumi Y, Jaakkola PM, Jäättelä M, Jackson GR, Jackson WT, Janji B, Jendrach M, Jeon JH, Jeung EB, Jiang H, Jiang H, Jiang JX, Jiang M, Jiang Q, Jiang X, Jiang X, Jiménez A, Jin M, Jin S, Joe CO, Johansen T, Johnson DE, Johnson GV, Jones NL, Joseph B, Joseph SK, Joubert AM, Juhász G, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Jung CH, Jung YK, Kaarniranta K, Kaasik A, Kabuta T, Kadowaki M, Kagedal K, Kamada Y, Kaminskyy VO, Kampinga HH, Kanamori H, Kang C, Kang KB, Kang KI, Kang R, Kang YA, Kanki T, Kanneganti TD, Kanno H, Kanthasamy AG, Kanthasamy A, Karantza V, Kaushal GP, Kaushik S, Kawazoe Y, Ke PY, Kehrl JH, Kelekar A, Kerkhoff C, Kessel DH, Khalil H, Kiel JA, Kiger AA, Kihara A, Kim DR, Kim DH, Kim DH, Kim EK, Kim HR, Kim JS, Kim JH, Kim JC, Kim JK, Kim PK, Kim SW, Kim YS, Kim Y, Kimchi A, Kimmelman AC, King JS, Kinsella TJ, Kirkin V, Kirshenbaum LA, Kitamoto K, Kitazato K, Klein L, Klimecki WT, Klucken J, Knecht E, Ko BC, Koch JC, Koga H, Koh JY, Koh YH, Koike M, Komatsu M, Kominami E, Kong HJ, Kong WJ, Korolchuk VI, Kotake Y, Koukourakis MI, Kouri Flores JB, Kovács AL, Kraft C, Krainc D, Krämer H, Kretz-Remy C, Krichevsky AM, Kroemer G, Krüger R, Krut O, Ktistakis NT, Kuan CY, Kucharczyk R, Kumar A, Kumar R, Kumar S, Kundu M, Kung HJ, Kurz T, Kwon HJ, La Spada AR, Lafont F, Lamark T, Landry J, Lane JD, Lapaquette P, Laporte JF, László L, Lavandero S, Lavoie JN, Layfield R, Lazo PA, Le W, Le Cam L, Ledbetter DJ, Lee AJ, Lee BW, Lee GM, Lee J, Lee JH, Lee M, Lee MS, Lee SH, Leeuwenburgh C, Legembre P, Legouis R, Lehmann M, Lei HY, Lei QY, Leib DA, Leiro J, Lemasters JJ, Lemoine A, Lesniak MS, Lev D, Levenson VV, Levine B, Levy E, Li F, Li JL, Li L, Li S, Li W, Li XJ, Li YB, Li YP, Liang C, Liang Q, Liao YF, Liberski PP, Lieberman A, Lim HJ, Lim KL, Lim K, Lin CF, Lin FC, Lin J, Lin JD, Lin K, Lin WW, Lin WC, Lin YL, Linden R, Lingor P, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Lisanti MP, Liton PB, Liu B, Liu CF, Liu K, Liu L, Liu QA, Liu W, Liu YC, Liu Y, Lockshin RA, Lok CN, Lonial S, Loos B, Lopez-Berestein G, López-Otín C, Lossi L, Lotze MT, Lőw P, Lu B, Lu B, Lu B, Lu Z, Luciano F, Lukacs NW, Lund AH, Lynch-Day MA, Ma Y, Macian F, MacKeigan JP, Macleod KF, Madeo F, Maiuri L, Maiuri MC, Malagoli D, Malicdan MC, Malorni W, Man N, Mandelkow EM, Manon S, Manov I, Mao K, Mao X, Mao Z, Marambaud P, Marazziti D, Marcel YL, Marchbank K, Marchetti P, Marciniak SJ, Marcondes M, Mardi M, Marfe G, Mariño G, Markaki M, Marten MR, Martin SJ, Martinand-Mari C, Martinet W, Martinez-Vicente M, Masini M, Matarrese P, Matsuo S, Matteoni R, Mayer A, Mazure NM, McConkey DJ, McConnell MJ, McDermott C, McDonald C, McInerney GM, McKenna SL, McLaughlin B, McLean PJ, McMaster CR, McQuibban GA, Meijer AJ, Meisler MH, Meléndez A, Melia TJ, Melino G, Mena MA, Menendez JA, Menna-Barreto RF, Menon MB, Menzies FM, Mercer CA, Merighi A, Merry DE, Meschini S, Meyer CG, Meyer TF, Miao CY, Miao JY, Michels PA, Michiels C, Mijaljica D, Milojkovic A, Minucci S, Miracco C, Miranti CK, Mitroulis I, Miyazawa K, Mizushima N, Mograbi B, Mohseni S, Molero X, Mollereau B, Mollinedo F, Momoi T, Monastyrska I, Monick MM, Monteiro MJ, Moore MN, Mora R, Moreau K, Moreira PI, Moriyasu Y, Moscat J, Mostowy S, Mottram JC, Motyl T, Moussa CE, Müller S, Muller S, Münger K, Münz C, Murphy LO, Murphy ME, Musarò A, Mysorekar I, Nagata E, Nagata K, Nahimana A, Nair U, Nakagawa T, Nakahira K, Nakano H, Nakatogawa H, Nanjundan M, Naqvi NI, Narendra DP, Narita M, Navarro M, Nawrocki ST, Nazarko TY, Nemchenko A, Netea MG, Neufeld TP, Ney PA, Nezis IP, Nguyen HP, Nie D, Nishino I, Nislow C, Nixon RA, Noda T, Noegel AA, Nogalska A, Noguchi S, Notterpek L, Novak I, Nozaki T, Nukina N, Nürnberger T, Nyfeler B, Obara K, Oberley TD, Oddo S, Ogawa M, Ohashi T, Okamoto K, Oleinick NL, Oliver FJ, Olsen LJ, Olsson S, Opota O, Osborne TF, Ostrander GK, Otsu K, Ou JH, Ouimet M, Overholtzer M, Ozpolat B, Paganetti P, Pagnini U, Pallet N, Palmer GE, Palumbo C, Pan T, Panaretakis T, Pandey UB, Papackova Z, Papassideri I, Paris I, Park J, Park OK, Parys JB, Parzych KR, Patschan S, Patterson C, Pattingre S, Pawelek JM, Peng J, Perlmutter DH, Perrotta I, Perry G, Pervaiz S, Peter M, Peters GJ, Petersen M, Petrovski G, Phang JM, Piacentini M, Pierre P, Pierrefite-Carle V, Pierron G, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Piras A, Piri N, Platanias LC, Pöggeler S, Poirot M, Poletti A, Poüs C, Pozuelo-Rubio M, Prætorius-Ibba M, Prasad A, Prescott M, Priault M, Produit-Zengaffinen N, Progulske-Fox A, Proikas-Cezanne T, Przedborski S, Przyklenk K, Puertollano R, Puyal J, Qian SB, Qin L, Qin ZH, Quaggin SE, Raben N, Rabinowich H, Rabkin SW, Rahman I, Rami A, Ramm G, Randall G, Randow F, Rao VA, Rathmell JC, Ravikumar B, Ray SK, Reed BH, Reed JC, Reggiori F, Régnier-Vigouroux A, Reichert AS, Reiners JJ Jr, Reiter RJ, Ren J, Revuelta JL, Rhodes CJ, Ritis K, Rizzo E, Robbins J, Roberge M, Roca H, Roccheri MC, Rocchi S, Rodemann HP, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Rohrer B, Roninson IB, Rosen K, Rost-Roszkowska MM, Rouis M, Rouschop KM, Rovetta F, Rubin BP, Rubinsztein DC, Ruckdeschel K, Rucker EB 3rd, Rudich A, Rudolf E, Ruiz-Opazo N, Russo R, Rusten TE, Ryan KM, Ryter SW, Sabatini DM, Sadoshima J, Saha T, Saitoh T, Sakagami H, Sakai Y, Salekdeh GH, Salomoni P, Salvaterra PM, Salvesen G, Salvioli R, Sanchez AM, Sánchez-Alcázar JA, Sánchez-Prieto R, Sandri M, Sankar U, Sansanwal P, Santambrogio L, Saran S, Sarkar S, Sarwal M, Sasakawa C, Sasnauskiene A, Sass M, Sato K, Sato M, Schapira AH, Scharl M, Schätzl HM, Scheper W, Schiaffino S, Schneider C, Schneider ME, Schneider-Stock R, Schoenlein PV, Schorderet DF, Schüller C, Schwartz GK, Scorrano L, Sealy L, Seglen PO, Segura-Aguilar J, Seiliez I, Seleverstov O, Sell C, Seo JB, Separovic D, Setaluri V, Setoguchi T, Settembre C, Shacka JJ, Shanmugam M, Shapiro IM, Shaulian E, Shaw RJ, Shelhamer JH, Shen HM, Shen WC, Sheng ZH, Shi Y, Shibuya K, Shidoji Y, Shieh JJ, Shih CM, Shimada Y, Shimizu S, Shintani T, Shirihai OS, Shore GC, Sibirny AA, Sidhu SB, Sikorska B, Silva-Zacarin EC, Simmons A, Simon AK, Simon HU, Simone C, Simonsen A, Sinclair DA, Singh R, Sinha D, Sinicrope FA, Sirko A, Siu PM, Sivridis E, Skop V, Skulachev VP, Slack RS, Smaili SS, Smith DR, Soengas MS, Soldati T, Song X, Sood AK, Soong TW, Sotgia F, Spector SA, Spies CD, Springer W, Srinivasula SM, Stefanis L, Steffan JS, Stendel R, Stenmark H, Stephanou A, Stern ST, Sternberg C, Stork B, Strålfors P, Subauste CS, Sui X, Sulzer D, Sun J, Sun SY, Sun ZJ, Sung JJ, Suzuki K, Suzuki T, Swanson MS, Swanton C, Sweeney ST, Sy LK, Szabadkai G, Tabas I, Taegtmeyer H, Tafani M, Takács-Vellai K, Takano Y, Takegawa K, Takemura G, Takeshita F, Talbot NJ, Tan KS, Tanaka K, Tanaka K, Tang D, Tang D, Tanida I, Tannous BA, Tavernarakis N, Taylor GS, Taylor GA, Taylor JP, Terada LS, Terman A, Tettamanti G, Thevissen K, Thompson CB, Thorburn A, Thumm M, Tian F, Tian Y, Tocchini-Valentini G, Tolkovsky AM, Tomino Y, Tönges L, Tooze SA, Tournier C, Tower J, Towns R, Trajkovic V, Travassos LH, Tsai TF, Tschan MP, Tsubata T, Tsung A, Turk B, Turner LS, Tyagi SC, Uchiyama Y, Ueno T, Umekawa M, Umemiya-Shirafuji R, Unni VK, Vaccaro MI, Valente EM, Van den Berghe G, van der Klei IJ, van Doorn W, van Dyk LF, van Egmond M, van Grunsven LA, Vandenabeele P, Vandenberghe WP, Vanhorebeek I, Vaquero EC, Velasco G, Vellai T, Vicencio JM, Vierstra RD, Vila M, Vindis C, Viola G, Viscomi MT, Voitsekhovskaja OV, von Haefen C, Votruba M, Wada K, Wade-Martins R, Walker CL, Walsh CM, Walter J, Wan XB, Wang A, Wang C, Wang D, Wang F, Wang F, Wang G, Wang H, Wang HG, Wang HD, Wang J, Wang K, Wang M, Wang RC, Wang X, Wang X, Wang YJ, Wang Y, Wang Z, Wang ZC, Wang Z, Wansink DG, Ward DM, Watada H, Waters SL, Webster P, Wei L, Weihl CC, Weiss WA, Welford SM, Wen LP, Whitehouse CA, Whitton JL, Whitworth AJ, Wileman T, Wiley JW, Wilkinson S, Willbold D, Williams RL, Williamson PR, Wouters BG, Wu C, Wu DC, Wu WK, Wyttenbach A, Xavier RJ, Xi Z, Xia P, Xiao G, Xie Z, Xie Z, Xu DZ, Xu J, Xu L, Xu X, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto A, Yamashina S, Yamashita M, Yan X, Yanagida M, Yang DS, Yang E, Yang JM, Yang SY, Yang W, Yang WY, Yang Z, Yao MC, Yao TP, Yeganeh B, Yen WL, Yin JJ, Yin XM, Yoo OJ, Yoon G, Yoon SY, Yorimitsu T, Yoshikawa Y, Yoshimori T, Yoshimoto K, You HJ, Youle RJ, Younes A, Yu L, Yu L, Yu SW, Yu WH, Yuan ZM, Yue Z, Yun CH, Yuzaki M, Zabirnyk O, Silva-Zacarin E, Zacks D, Zacksenhaus E, Zaffaroni N, Zakeri Z, Zeh HJ 3rd, Zeitlin SO, Zhang H, Zhang HL, Zhang J, Zhang JP, Zhang L, Zhang L, Zhang MY, Zhang XD, Zhao M, Zhao YF, Zhao Y, Zhao ZJ, Zheng X, Zhivotovsky B, Zhong Q, Zhou CZ, Zhu C, Zhu WG, Zhu XF, Zhu X, Zhu Y, Zoladek T, Zong WX, Zorzano A, Zschocke J, Zuckerbraun B (2012) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8: 445–544.

Knights CD, Catania J, Di Giovanni S, Muratoglu S, Perez R, Swartzbeck A, Quong AA, Zhang X, Beerman T, Pestell RG, Avantaggiati ML (2006) Distinct p53 acetylation cassettes differentially influence gene-expression patterns and cell fate. J Cell Biol 173: 533–544.

Korolchuk VI, Mansilla A, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC (2009) Autophagy inhibition compromises degradation of ubiquitin-proteasome pathway substrates. Mol Cell 33: 517–527.

Lain S, Hollick JJ, Campbell J, Staples OD, Higgins M, Aoubala M, McCarthy A, Appleyard V, Murray KE, Baker L, Thompson A, Mathers J, Holland SJ, Stark MJ, Pass G, Woods J, Lane DP, Westwood NJ (2008) Discovery, in vivo activity, and mechanism of action of a small-molecule p53 activator. Cancer Cell 13: 454–463.

Li L, Wang L, Li L, Wang Z, Ho Y, McDonald T, Holyoake TL, Chen W, Bhatia R (2012) Activation of p53 by SIRT1 inhibition enhances elimination of CML leukemia stem cells in combination with imatinib. Cancer Cell 21: 266–281.

Lin K, Adamson J, Johnson GG, Carter A, Oates M, Wade R, Richards S, Gonzalez D, Matutes E, Dearden C, Oscier DG, Catovsky D, Pettitt AR (2012) Functional analysis of the ATM-p53-p21 pathway in the LRF CLL4 trial: blockade at the level of p21 is associated with short response duration. Clin Cancer Res 18: 4191–4200.

Lin TT, Hewamana S, Ward R, Taylor H, Payne T, Pratt G, Baird D, Fegan C, Pepper C (2008) Highly purified CD38 sub-populations show no evidence of preferential clonal evolution despite having increased proliferative activity when compared with CD38 sub-populations derived from the same chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patient. Br J Haematol 142: 595–605.

MacCallum SF, Groves MJ, James J, Murray K, Appleyard V, Prescott AR, Drbal AA, Nicolaou A, Cunningham J, Haydock S, Ganley IG, Westwood NJ, Coates PJ, Lain S, Tauro S (2013) Dysregulation of autophagy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with the small-molecule Sirtuin inhibitor Tenovin-6. Sci Rep 3: 1275.

McCarthy AR, Pirrie L, Hollick JJ, Ronseaux S, Campbell J, Higgins M, Staples OD, Tran F, Slawin AM, Lain S, Westwood NJ (2012) Synthesis and biological characterisation of sirtuin inhibitors based on the tenovins. Bioorg Med Chem 20: 1779–1793.

McCarthy AR, Sachweh MC, Higgins M, Campbell J, Drummond CJ, van Leeuwen IM, Pirrie L, Ladds MJ, Westwood NJ, Laín S (2013) Tenovin-D3, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of Sirtuin SirT2, increases p21 (CDKN1A) expression in a p53-independent manner. Mol Cancer Ther 12: 352–360.

Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Kudalkar P, Cesar D, Murphy EJ, Koduru P, Ferrarini M, Zupo S, Cutrona G, Damle RN, Wasil T, Rai KR, Hellerstein MK, Chiorazzi N (2005) In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J Clin Invest 115: 755–764.

Mimnaugh EG, Chen HY, Davie JR, Celis JE, Neckers L (1997) Rapid deubiquitination of nucleosomal histones in human tumor cells caused byproteasome inhibitors and stress response inducers: effects on replication, transcription, translation, and the cellular stress response. Biochemistry 36: 14418–14429.

Mohr J, Helfrich H, Fuge M, Eldering E, Bühler A, Winkler D, Volden M, Kater AP, Mertens D, Te Raa D, Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Zenz T (2011) DNA damage-induced transcriptional program in CLL: biological and diagnostic implications for functional p53 testing. Blood 117: 1622–1632.

Napoli M, Flores ER (2013) The family that eats together stays together: new p53 family transcriptional targets in autophagy. Genes Dev 27: 971–974.

Natoni A, Murillo LS, Kliszczak AE, Catherwood MA, Montagnoli A, Samali A, O’Dwyer M, Santocanale C (2011) Mechanisms of action of a dual Cdc7/Cdk9 kinase inhibitor against quiescent and proliferating CLL cells. Mol Cancer Ther 10: 1624–1634.

Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD, Stewart G, Cawley JC, Taylor AM, Stankovic T (2001) p53 dysfunction in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: inactivation of ATM as an alternative to TP53 mutation. Blood 98: 814–822.

Pirrie L, McCarthy AR, Major LL, Morkūnaitė V, Zubrienė A, Matulis D, Lain S, Lebl T, Westwood NJ (2012) Discovery and validation of SIRT2 inhibitors based on tenovin-6: use of a 1H-NMR method to assess deacetylase activity. Molecules 17: 12206–122024.

Rosenwald A, Chuang EY, Davis RE, Wiestner A, Alizadeh AA, Arthur DC, Mitchell JB, Marti GE, Fowler DH, Wilson WH, Staudt LM (2004) Fludarabine treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia induces a p53-dependent gene expression response. Blood 104: 1428–1434.

Sunami Y, Araki M, Hironaka Y, Morishita S, Kobayashi M, Liew EL, Edahiro Y, Tsutsui M, Ohsaka A, Komatsu N (2013) Inhibition of the NAD-dependent protein deacetylase SIRT2 induces granulocytic differentiation in human leukemia cells. PLoS One 8: e57633.

Taatjes DJ, Sobel BE, Budd RC (2008) Morphological and cytochemical determination of cell death by apoptosis. Histochem Cell Biol 129: 33–43.

Tauro S, Hepburn MD, Peddie CM, Bowen DT, Pippard MJ (2002) Functional disturbance of marrow stromal microenvironment in the myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 16: 785–790.

Yuan H, Wang Z, Li L, Zhang H, Modi H, Horne D, Bhatia R, Chen W (2012) Activation of stress response gene SIRT1 by BCR-ABL promotes leukemogenesis. Blood 119: 1904–1914.

Zembruski NC, Stache V, Haefeli WE, Weiss J (2012) 7-Aminoactinomycin D for apoptosis staining in flow cytometry. Anal Biochem 429: 79–81.

Zenz T, Kröber A, Scherer K, Häbe S, Bühler A, Benner A, Denzel T, Winkler D, Edelmann J, Schwänen C, Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S (2008) Monoallelic TP53 inactivation is associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a detailed genetic characterization with long-term follow-up. Blood 112: 3322–3329.

Acknowledgements

We thank TENOVUS Tayside for funding the study and Dr Andrew Cassidy, Genetics Core Services Manager, Medical Research Institute, University of Dundee for TP53 sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Groves, M., Johnson, C., James, J. et al. p53 and cell cycle independent dysregulation of autophagy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Cancer 109, 2434–2444 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.601

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.601

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The sirtuin 1/2 inhibitor tenovin-1 induces a nonlinear apoptosis-inducing factor-dependent cell death in a p53 null Ewing’s sarcoma cell line

Investigational New Drugs (2018)

-

Tenovin-6 impairs autophagy by inhibiting autophagic flux

Cell Death & Disease (2017)

-

SIRT1 and SIRT2 inhibition impairs pediatric soft tissue sarcoma growth

Cell Death & Disease (2014)