Abstract

Background:

The 1997 international consensus conference on renal cell cancer (RCC) prognosis suggested erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and anaemia as prognostic biomarkers, but most studies reviewed were limited by small sample sizes.

Methods:

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate whether ESR, ALP, haemoglobin (Hb), and haematocrit (Hct) could predict survival outcomes in 1307 patients with clear cell RCC (ccRCC) who underwent nephrectomy during 1994–2008.

Results:

During a median follow-up of 43 months, we found that the patients with preoperative high levels of ESR, had a 2.10-fold (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.21–3.67) greater risk of dying from RCC compared with patients with low levels (normal range). Patients with preoperative anaemia, assessed by Hb and Hct, had a 3.11-fold (95% CI: 1.17–8.25) and 6.20-fold (95% CI: 2.30–16.72) greater risk of dying from other illnesses, respectively, compared with patients without anaemia. ALP levels were not associated with ccRCC patients’ survival. These associations for ESR and anaemia were more pronounced in patients with body mass index (BMI) <25 compared with patients with BMI ⩾25 kg m−2.

Conclusion:

Preoperative high ESR, but not ALP, was a significant predictor for cancer-specific survival among ccRCC patients. Anaemia increases the risk of death from other illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The age-standardised kidney cancer incidence rates per 100 000 population have risen from 3.0 in 1999 to 5.1 in 2009 in Korea (Jung et al, 2012). During a similar time period, the 5-year relative survival rates have also increased from 62% during 1993–1995 to 77.1% during 2005–2009 (Jung et al, 2012). Of the renal cell carcinoma (RCC) subtypes, clear cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most common, representing 70% of all RCCs (Cheville et al, 2003), and is characterised by the loss of the short arm of chromosome 3p (Presti et al, 1991).

Several biomarkers for RCC patients were proposed to be associated with RCC prognosis in the 1997 international consensus conference, convened by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC); such factors included erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anaemia (defined by haemoglobin; Hb), serum calcium, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (Srigley et al, 1997). Anaemia has been identified in 35–52% of RCC patients and is associated with more advanced disease and worse survival (Kim et al, 2003; Magera et al, 2008; Jensen et al, 2009). The ESR is a non-specific measure of inflammatory response (Brigden, 1999) and RCC patients with high-stage and high-grade tumour had high levels of ESR (Sengupta et al, 2006). A recent meta-analysis has shown that elevated ESR levels were associated with poor overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and recurrence-free survival (RFS) (Wu et al, 2011). Some studies, but not all (Magera et al, 2008), have observed that elevated ALP levels, a possible sign of paraneoplastic syndrome of RCC patients, were associated with poor RCC survival (Lee et al, 2006; Kume et al, 2011).

Most studies published to date on RCC prognosis included small sample sizes or did not take into account distinct histological subtypes or stages of RCC. We therefore evaluated whether the preoperative high levels of ESR, ALP, or anaemia, which are routinely measured parameters, could predict worse survival outcomes of ccRCC patients treated with radical or partial nephrectomy in a clinical-based cohort study containing large numbers of patients and information about histological subtypes and stages of RCC.

Materials and methods

Study patients

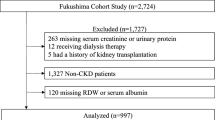

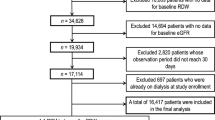

This study has been described elsewhere (Choi et al, 2012). We included 1307 patients who underwent initial nephrectomy for ccRCC at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea, between October 1994 and December 2008. Patients were excluded if they had missing information on the main exposures of interest, ESR (n=81) or ALP variables (n=1), leaving 1226 and 1306 patients, respectively. In all, 1307 patients were included for analyses of Hb and haematocrit (Hct).

The primary end points were OS, CSS, and other-cause survival (OCS), defined as the elapsed time between the date of surgery and either the date of death from any cause, from RCC, and from causes other than RCC, respectively, or 31 December 2008. This study was approved by an institutional review board at the Samsung Medical Centre.

Data collection

All patients received a clinical and pathological review. Data were manually abstracted from the electronic medical records using a standardised data collection form. At diagnosis, patients were asked about their smoking and alcohol habits, and whether they ever had RCC-related symptoms or weight loss compared with their usual weight. Height and weight were directly measured. All patients had a clinical abdominal computed tomography scan before surgery for the status of regional lymph nodes near the kidney and the presence of distant metastases. Tumour staging was confirmed by microscopic examination of surgically resected specimens of RCC. The size and location of tumours were measured at the time of macroscopic examination. The histological subtypes were classified as: clear cell, papillary, chromophobe, collecting duct RCC, and unclassified cell carcinoma (Kovacs et al, 1997). The tumour grade was based on the Fuhrman nuclear grading system (Fuhrman et al, 1982). The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score was assessed by anaesthesiologists.

Cause of death

Death information of all patients was collected based on our institution’s vital records data, which incorporated both in-hospital death data at our institution and data from the Korean National Statistical Office (KNSO). If the cases where the death occurred out of our institution, the patient’s medical records were electronically linked to death certificates via unique 13-digit personal identification number in the KNSO, the system of which complete ascertainment of cause for deaths reached to 96.2% (Korean National Statistical Office, 2010). Causes of death were ascertained and verified by a medical record review by physicians, the patient’s death certificate, or autopsy report, and coded according to the Korean Standard Classification of Causes of Death (Korean National Statistical Office, 1995), which was based on the International Classification of Disease for Oncology 10th edition (World Health Organization, 1992).

Laboratory assays

Venous blood samples were collected as part of routine clinical procedures before surgery at our institution and laboratory parameters for this study were abstracted from medical records. The ESR was measured using the quantitative capillary photometry method (TEST-1 system, Alifax, Italy) with the inter- and intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) for ESR was ⩽10%. Haemoglobin was measured using the cyanide-free haemoglobin spectrophotometry method and Hct was measured using electric impedance (SYSEMX XE-2100, Kobe, Japan) with the inter- and intra-assay CVs of ⩽3% for Hb and Hct. ALP was measured using the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry method (Roche modular DP-210, Mannheim, Germany) with the inter- and intra-assay CVs of ⩽1.4%.

To define cutoff points for high levels (abnormal laboratory values) of ESR and ALP, the gender-specific cutoff values from a priori study were referred to: ESR—males >22 mm per hour, females >29 mm per hour (Magera et al, 2008); the cutoff point for ALP was >115U l−1 for both sexes (Motzer et al, 1999). The anaemia was defined using the following cutoff points: Hb—males <13.5 g dl−1, females <12 g dl−1; and Hct—males <41%, females <36% (Magera et al, 2008). We also analysed the data with reference values used at our institution as follows: ESR—males 0–22 mm per hour; females 0–27 mm per hour; ALP—males 53–128 U l−1; females 42–98 U l−1; Hb—males 13.6–17.4 g dl−1; females 11.2–14.8 g dl−1; Hct—males 40.4–51.3%; females 31.8–43.8%.

Statistical analysis

Because ccRCC represents a distinct clinical entity in relation to pathogenesis and genetic alterations from other histological subtypes of RCC (Presti et al, 1991; Cheville et al, 2003), we restricted the analysis to only patients with ccRCC in the main analysis. The Kaplan–Meier model was used to estimate survival rates, and the Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to estimate multivariate-adjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We conducted three separate multivariate analyses. The first model was stratified by age at diagnosis (years) and sex. The second model was further adjusted for body mass index (BMI) (continuous), smoking (never or ever), weight loss (yes or no), tumour stage (pT1, pT2, or pT3-4), nephrectomy type (radical or partial), Fuhrman grade (G1-2 or G3-4), symptom presence (yes or no), tumour size (<5 or ⩾5 cm), and ASA class (<2 or ⩾2). The third model additionally simultaneously adjusted for the other all exposures of interest (ESR, ALP, and anaemia) in addition to the covariates listed above. Adjustment for alcohol did not appreciably change the results; therefore, we did not include this in the analyses. We used the false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment <0.05 as the significance threshold in each of the tests to account for multiple comparisons (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). The study also evaluated whether tumour stage (pT-2 or pT3-4) or preoperative BMI (<25 or ⩾25 kg m−2) (Steering Committee of the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization, the International Association for the Study of Obesity, the International Obesity Task Force, 2000), modified the associations. In the sensitivity analyses, patients who had metastases (n=78) or those who died due to any cause within the first 2-year follow-up period after surgery (n=79) were excluded to reduce the potential effects of reverse causality. All P-values reported are two sided, with P<0.05 used to denote statistical significance. The analyses were performed using the STATA (version 11; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics prior to surgery

During a median follow-up of 43 months, 165 of 1307 patients (12.6%) died from any cause, 135 patients (10.3%) died from RCC, and 30 patients (2.3%) died from causes unrelated to RCC. Based on the cutoff points for preoperative laboratory values, high levels of ESR and ALP were observed in 31.2% and 7% of patients, respectively. Approximately 25.7% and 28.9% of patients were classified as anaemic based on the levels of Hb and Hct, respectively. Patients who died from any cause during the follow-up period were more likely to be older, non-alcohol drinkers and had lower BMI, weight loss, higher ASA class (⩾2), larger RCC (⩾5 cm), radical nephrectomy, higher stage (pT3-4), higher Fuhrman grade (G3-4), and RCC symptom or metastases compared with those who were still alive during the study follow-up period (Table 1). Patients who died also had higher levels of ESR and ALP, but lower levels of Hb and Hct compared with those who were still alive.

Survival outcomes

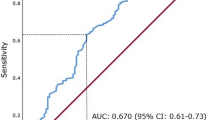

Patients with high levels of ESR and ALP had a significantly lower 5-year CSS rates (95% CI) compared with patients with low levels: 73.9% (67.7–79.1) and 95.7% (93.6–97.2) for ESR and 65.0% (51.8–75.3) and 90.6% (88.3–92.4) for ALP values (Plog rank test<0.01) (Figure 1). The patients who had anaemia before surgery, defined by either low Hb or Hct, also had significantly poorer 5-year CSS rates compared with those without anaemia: 74.5% (68.4–79.5) and 93.9% (91.7–95.6) for Hb and 78.7% (73.4–83.1) and 93.1% (90.7–94.9) for Hct (Plog rank test<0.01). The corresponding 5-year OS rates were 71.5% (65.2–76.8) and 93.5% (91.1–95.2) for ESR values, 62.4% (49.4–73.0) and 88.1% (85.7–90.2) for ALP values, 70.5% (64.3–75.8) and 92.1% (89.7–93.9) for Hb, and 73.4% (67.8–78.1) and 92.1% (89.6–94.0) for Hct (Plog rank test<0.01).

Cancer-specific survival curves for ESR, ALP, and anaemia. (A) ESR; (B) ALP; (C) Hb; (D) Hct. ESR=erythrocyte sedimentation rate. ALP=alkaline phosphatase; Hb=haemoglobin, and Hct=haematocrit. Note: Cutoff points for high levels (abnormal laboratory values) were as follows: ESR:>22 mm per hour for males, >29 mm per hour for females; ALP:>115U l−1 for both males and females; Cutoff points for anaemia were as follows: Hb:<13.5 g dl−1 for males, <12 g dl−1 for females; Hct:<41% for males, <36% for females.

Multivariate analyses

Age- and sex-adjusted models showed poorer OS and CSS with high levels of ESR or ALP and poorer OS, CSS, and OCS with low levels of Hb or Hct, compared with high levels of each (Model 1). Further adjustment for clinical and pathological factors attenuated these associations (Model 2). With analyses considering all exposure variables simultaneously (Model 3), we found that patients with high ESR levels had poorer CSS compared with patients with low levels, with a HR of 2.10 (95% CI: 1.21–3.67) (Table 2). Anaemic patients before surgery had lower OS and OCS compared with non-anaemic patients. Comparing patients with anaemia to patients without, the HRs (95% CIs) were 2.01 (1.22–3.29) for OS and 3.11 (1.17–8.25) for OCS in relation to Hb levels; and 1.90 (1.18–3.05) for OS and 6.20 (2.30–16.72) for OCS in relation to Hct levels. However, we found no significant associations between ALP levels and survival outcomes. Multiple comparison correction by controlling the FDR, which provides a useful alternative to traditional multiple testing method, further corroborated that preoperative high ESR levels, but not ALP, were a significant predictor for CSS (PFDR adjusted <0.01). Anaemia was a significant predictor for OS (PFDR adjusted <0.05 for both Hb and Hct) as well as OCS (PFDR adjusted <0.05 for both Hb and Hct). In additional analyses, we analysed the data using our institution‘s cutoff values for further comparisons and observed similar associations as shown in Model 3 of Table 2. Compared patients with high ESR levels to patients with low ESR levels, HR was 2.15 (95% CI: 1.25–3.69). Compared patients with anaemia to patients without, HRs (95% CIs) were 1.80 (1.13–2.86) for OS and 3.38 (1.33–8.60) for OCS in relation to Hb levels; and 1.50 (0.93–2.40) for OS and 3.14 (1.23–7.98) for OCS in relation to Hct levels. In addition, we repeated the above main analyses by including the patients with all histological subtypes and found that the associations were slightly attenuated (data not shown).

When stratifying the analyses by stages (pT1-2 or pT3-4), a significant interaction was observed between ESR and CSS (P interaction=0.027), with HRs (95% CI) of 2.30 (1.07–4.93) for patients with low stage and 1.12 (0.25–5.04) for patients with high stage (Table 3). A significant interaction was observed for ALP levels associated with OS (P interaction=0.028), but the association did not reach statistical significance. When stratifying the analyses by BMI (<25 or ⩾25 kg m−2), the associations between ESR levels, OS, and CSS varied by BMI (P interaction<0.05, Table 4): compared to patients with low ESR levels, those with high ESR levels had a 3.53 times (95% CI: 1.51–8.23) higher risk of death from RCC in the group with BMI of<25 kg m−2. The associations between anaemia and CSS varied by BMI (P interaction <0.05). Although there was no interaction for OS, patients with anaemia (defined by levels of Hb and Hct) had a 2.22 times (95% CI: 1.12–4.40) and 2.19 times (95% CI: 1.09–4.38) higher risk of death from RCC in the group with BMI of <25 kg m−2 compared with patients without anaemia, respectively. The exclusion of patients with metastasis or those who died within the first 2 years of follow-up did not substantially alter the main findings (data now shown).

Discussion

We found that high ESR levels and anaemia before surgery had adverse prognostic significance for RCC survival among Korean patients with ccRCC. The patients with preoperative high ESR levels had a 2.10-fold higher risk of dying from RCC compared to those with low ESR levels. The anaemic patients, defined by levels of Hb and Hct, had a 3.11-fold and 6.20-fold higher risk of dying from other illness compared with those without anaemia, respectively. We also found that the patients with preoperative high ALP levels had poorer survival outcomes compared to those low ALP levels, but there were no statistically significance. Additionally, restricting the analysis to patients with metastases did not change the results materially (data not shown). Poorer CSS with high ESR levels and poorer OS with anaemia were more pronounced among patients with BMI <25 kg m−2.

The AJCC/UICC concluded that ALP, ESR, and anaemia could be used as prognostic markers in RCC patients (Srigley et al, 1997). However, the conclusion made by the experts was based on a narrative review of a limited number of studies, which included small sample sizes and did not consider important clinical and pathological characteristics. A recent meta-analysis of 14 studies has indicated that ESR could be a prognostic indicator for OS, CSS, and RFS, with the summary HRs (95% CIs) of 1.86 (1.34–2.59), 3.85 (3.31–4.48), and 3.88 (1.52–9.92), respectively (Wu et al, 2011). In this study, high ESR levels were a stronger prognostic factor for CSS compared with OS or OCS. In a simultaneous analysis of all three exposure variables (ESR, ALP, and Hb or Hct), only ESR was significantly associated with CSS, which suggests an important role of inflammation in RCC progression. Inflammatory cells have been suggested to promote carcinogenesis, possibly by increasing DNA damage, stimulating tumour cell proliferation, and promoting metastasis and angiogenesis (Coussens and Werb, 2002; Colotta et al, 2009).

ALP, an enzyme produced naturally by the body, may be a sensitive indicator of bone or liver metastasis, as ALP levels can reflect liver or bone dysfunction (Kaplan, 1972). High ALP levels were frequently observed in kidney patients and may be linked to paraneoplastic syndrome due to a tumour per se, or bone or liver metastases (Stolbach et al, 1969; Laski and Vugrin, 1987; Sufrin et al, 1989). Some studies have indicated that a high ALP level may be an adverse independent predictor of CSS in non-metastatic patients, of progression-free survival in overall patients (Lee et al, 2006), and of OS in patients with bone metastasis (Kume et al, 2011). The lack of associations between ALP and survival outcomes in the present analysis, however, did not support the hypothesis that ALP can be a useful prognostic marker for RCC, suggesting that ESR rather than ALP may be the more relevant factor in RCC prognosis.

The presence of anaemia at diagnosis has been hypothesised to be an independent adverse prognostic indicator for CSS in patients with ccRCC (Kim et al, 2003; Magera et al, 2008) and for RFS in patients with all subtypes (Jensen et al, 2009). In our study, anaemic patients at diagnosis had a greater risk of death due to other illnesses, but not for CSS, compared with those without anaemia. Anaemia may be an important contributor to a worse cancer prognosis, presumably by affecting tumour hypoxia, a low quality of life, or poor responses to treatment (Littlewood, 2001). There is evidence that tumour hypoxia may play a negative role in cancer treatment and survival, either directly by the scarcity of oxygen that is observed to be resistant to ionising radiation-induced DNA damage in tumours, or indirectly through stimulating proteomic and genomic changes that subsequently lead to tumour progression, metastatic potential, and a poor clinical prognosis (Hockel and Vaupel, 2001; Littlewood, 2001). Anaemia may also be an indicative of patient’s physical weakness, undernutrition, and susceptibility of infection; therefore, a preoperative predisposition to poor general health condition may result in poor prognosis.

Given that a high BMI was related to a better OS and CSS (Choi et al, 2012), we examined whether BMI modified the associations and found more apparent associations for high ESR and anaemia with survival among patients with BMI <25 than among patients with BMI ⩾25 kg m−2. This may be partly because patients with a low weight could be more susceptible to inflammation, undernutrition, or anaemia, but the potential mechanism by which the combination of inflammation or anaemia and low BMI worsens survival outcomes needs to be further elucidated.

The present study has several limitations. There may be the possibility that a confounding bias by unmeasured or residual confounding factors may exist, but efforts were made to adjust for important known clinical and pathological features for RCC prognosis. We also conducted stratified analyses by BMI and stage, which were associated with RCC survival in our data (Choi et al, 2012), and found significant associations for patients with low stage or low BMI. Because results from our study may not necessarily be generalised to other patient populations, further studies are needed to replicate the results of the present study in different ethnicities. However, the inclusion of patients at the large general hospital that is well-equipped with medical care facilities, an electronic medical record system, and highly precise mortality data could be the strengths of this study, minimising misclassification bias. Also, this study included large sample sizes, with a long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that preoperative ESR is an independent prognostic indicator for CSS and anaemia is related to a high risk of death due to other causes than RCC among patients with ccRCC. These prognostic markers could allow the identification of optimal therapeutic strategies on clinical outcomes for ccRCC patients with preoperative high levels of ESR and anaemia and, at the same time, improve patients’ prognosis. Further studies are needed to replicate the results of the present study in different patient populations.

Change history

05 February 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B (Method) 57: 289–300

Brigden ML (1999) Clinical utility of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Am Fam Physician 60: 1443–1450

Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Zincke H, Weaver AL, Blute ML (2003) Comparisons of outcome and prognostic features among histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 27: 612–624

Choi Y, Park B, Jeong B, Seo S, Jeon S, Choi H, Adami H, Lee J, Lee H (2012) Body mass index and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: a clinical-based cohort and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 132 (3): 625–634

Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A (2009) Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 30: 1073–1081

Coussens LM, Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420: 860–867

Fuhrman SA, Lasky LC, Limas C (1982) Prognostic significance of morphologic parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 6: 655–663

Hockel M, Vaupel P (2001) Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst 93: 266–276

Jensen HK, Donskov F, Marcussen N, Nordsmark M, Lundbeck F, von der Maase H (2009) Presence of intratumoral neutrophils is an independent prognostic factor in localized renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 4709–4717

Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, Lee JS (2012) Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Res Treat 44: 11–24

Kaplan MM (1972) Alkaline phosphatase. N Engl J Med 286: 200–202

Kim HL, Belldegrun AS, Freitas DG, Bui MH, Han KR, Dorey FJ, Figlin RA (2003) Paraneoplastic signs and symptoms of renal cell carcinoma: implications for prognosis. J Urol 170: 1742–1746

Korean National Statistical Office (2010) Annual Report on the Cause of Death Statistics (Based on Vital Registration) pp 254. Korean National Statistical Office: Daejeon

Korean National Statistical Office (1995) Korea Standard Classification of Cause of Death (KCD) 3rd revision Korean National Statistical Office: Seoul

Kovacs G, Akhtar M, Beckwith BJ, Bugert P, Cooper CS, Delahunt B, Eble JN, Fleming S, Ljungberg B, Medeiros LJ, Moch H, Reuter VE, Ritz E, Roos G, Schmidt D, Srigley JR, Storkel S, van den Berg E, Zbar B (1997) The Heidelberg classification of renal cell tumours. J Pathol 183: 131–133

Kume H, Kakutani S, Yamada Y, Shinohara M, Tominaga T, Suzuki M, Fujimura T, Fukuhara H, Enomoto Y, Nishimatsu H, Homma Y (2011) Prognostic factors for renal cell carcinoma with bone metastasis: who are the long-term survivors? J Urol 185: 1611–1614

Laski ME, Vugrin D (1987) Paraneoplastic syndromes in hypernephroma. Semin Nephrol 7: 123–130

Lee SE, Byun SS, Han JH, Han BK, Hong SK (2006) Prognostic significance of common preoperative laboratory variables in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int 98: 1228–1232

Littlewood TJ (2001) The impact of hemoglobin levels on treatment outcomes in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol 28: 49–53

Magera JS, Leibovich BC, Lohse CM, Sengupta S, Cheville JC, Kwon ED, Blute ML (2008) Association of abnormal preoperative laboratory values with survival after radical nephrectomy for clinically confined clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology 71: 278–282

Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J (1999) Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 17: 2530–2540

Presti JC, Rao PH, Chen Q, Reuter VE, Li FP, Fair WR, Jhanwar SC (1991) Histopathological, cytogenetic, and molecular characterization of renal cortical tumors. Cancer Res 51: 1544–1552

Sengupta S, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, Leibovich BC, Thompson RH, Webster WS, Frank I, Zincke H, Blute ML, Kwon ED (2006) The preoperative erythrocyte sedimentation rate is an independent prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 106: 304–312

Srigley JR, Hutter RV, Gelb AB, Henson DE, Kenney G, King BF, Raziuddin S, Pisansky TM (1997) Current prognostic factors--renal cell carcinoma: Workgroup No. 4. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Cancer 80: 994–996

Steering Committee of the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization, the International Association for the Study of Obesity, the International Obesity Task Force (2000) The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Health Communications Australia Pty Limited

Stolbach LL, Krant MJ, Fishman WH (1969) Ectopic production of an alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 281: 757–762

Sufrin G, Chasan S, Golio A, Murphy GP (1989) Paraneoplastic and serologic syndromes of renal adenocarcinoma. Semin Urol 7: 158–171

World Health Organization (1992) International Classifications of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death 10th ed World Health Organization: Geneva

Wu Y, Fu X, Zhu X, He X, Zou C, Han Y, Xu M, Huang C, Lu X, Zhao Y (2011) Prognostic role of systemic inflammatory response in renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 137: 887–896

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, Y., Park, B., Kim, K. et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and anaemia are independent predictors of survival in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 108, 387–394 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.565

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.565

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A practical prognostic peripheral blood-based risk model for the evaluation of the likelihood of a response and survival of metastatic cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Prognostic role of pretreatment thrombocytosis on survival in patients with cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2019)

-

Inflammation marker ESR is effective in predicting outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

BMC Cancer (2018)

-

Validation of a fractional model for erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Computational and Applied Mathematics (2018)

-

Single measurement of hemoglobin predicts outcome of HCC patients

Medical Oncology (2014)