Abstract

Background:

Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 predispose to pancreatic cancer. We estimated the incidence of pancreatic cancer in a cohort of female carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. We also estimated survival rates in pancreatic cancer cases from families with a BRCA mutation.

Methods:

We followed 5149 women with a mutation for new cases of pancreatic cancer. The standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for pancreatic cancer were calculated based on age group and country of residence. We also reviewed the pedigrees of 8140 pedigrees with a BRCA1 or a BRCA2 mutation for those with a case of pancreatic cancer. We recorded the year of diagnosis and the year of death for 351 identified cases.

Results:

Eight incident pancreatic cancer cases were identified among all mutation carriers. The SIR for BRCA1 carriers was 2.55 (95% CI=1.03–5.31, P=0.04) and for BRCA2 carriers was 2.13 (95% CI=0.36–7.03, P=0.3). The 5-year survival rate was 5% for cases from a BRCA1 family and 4% for cases from a BRCA2 family.

Conclusion:

The risk of pancreatic cancer is approximately doubled in female BRCA carriers. The poor survival in familial pancreatic cancer underscores the need for novel anti-tumoural strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Germline mutations in various cancer susceptibility genes have been implicated in the pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. These include BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Lal et al, 2000), TP53 (Caldas et al, 1994), PALB2 (Jones et al, 2009), p16/CDKN2A (Redston et al, 1994; Ghiorzo et al, 2012), SMAD4 (Hahn et al, 1996), STK 11 (Sato et al, 2001), ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) gene (Roberts et al, 2011) and the mismatch repair genes (MMR) (Win et al, 2012). Familial pancreatic cancer accounts for about 5–10% of pancreatic cancers (Fernandez et al, 1994; Klein et al, 2001; Bartsch et al, 2004). In a study of 102 familial pancreatic cancer patients, Lal et al (2000) identified five germline mutations: three mutations in BRCA2 gene and one mutation each in BRCA1 and p16.

Several other lines of evidence also suggest that carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations face an increased risk of pancreatic cancer (Phelan et al, 1996; The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1999; Thompson et al, 2002; Risch et al, 2006). In the cross-sectional study of The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (1999), Thompson et al (2002) reported a significant increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers (RR=2.26, 95% CI=1.26–4.06, P=0.004) and in BRCA2 mutation carriers (RR=3.51, 95% CI=1.87–6.58, P=0.0012). In a study of 1171 unselected patients with ovarian cancer in Ontario, Risch et al (2006) estimated the risk of pancreatic cancer among relatives of 977 proband patients with invasive ovarian cancer, including 127 with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. The relative risk for pancreatic cancer was 3.1 (95% CI=0.45–21) in relatives of BRCA1 mutation carriers and 6.6 (95% CI=1.9–23) in relatives of BRCA2 mutation carriers, compared with the relatives of non-carriers.

All previous studies are based on reviews of family histories and the diagnoses of pancreatic cancer relied on accurate information provided by a family member. Further, in previous studies, the mutation status of the pancreatic cancer cases was unknown. We have conducted the first prospective study of the incidence of pancreatic cancer in a cohort of BRCA1 and the BRCA2 mutation carriers. The knowledge of pancreatic cancer incidence rates has important implications for genetic counsellors and potentially for informing screening policies. We also estimated the survival rate of pancreatic cancer in cases from families with a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Information on current survival rates may be relevant before initiating therapies for women or men with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation.

Materials and methods

Incidence

We estimated the incidence of pancreatic cancer in a cohort 5149 women with a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation in women who completed a baseline questionnaire and who had completed at least one follow-up questionnaire. The cohort was assembled from 50 study centres in 10 different countries. The 5149 carriers were from 3878 different families. Each woman was proven to be a carrier of a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 by direct DNA sequencing. Women with a past history of breast cancer or of skin cancer were eligible for the study but women with a past history of ovarian cancer or of another cancer were excluded. All women had completed a risk questionnaire at study entry and a follow-up questionnaire every 2 years thereafter. The baseline and follow-up questionnaires were standardised across the study centres. Women were followed from the date at the baseline until the date of last questionnaire, the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, diagnosis of ovarian cancer or death from another cause. Of 5149 women, 60 women had data missing on key variables (e.g., date of birth, date of questionnaires, gene mutation) and were excluded, leaving 5089 women in final analysis. The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was confirmed by reference to a pathology report or medical record where possible.

The risk of pancreatic cancer in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, relative to the general population, was estimated with standardised incidence ratios (SIRs). The SIR was obtained by calculating the ratio of observed to expected number of new pancreatic cancer cases, for all women combined and then separately for BRCA1 and the BRCA2 carriers. To do so, the observed and expected numbers of pancreatic cancers were derived separately for carriers from each of five countries (Canada, United States, Poland, France and Italy). First, the annual age-standardised incidence rates of pancreatic cancer were calculated with the count (numerator) and person-year at risk (denominator). The person-years at risk were calculated using the total number of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers multiplied with the average follow-up time in years. The person-years were subcategorised according to different countries and different age groups. The age-standardised incidence rates for each participating country were obtained from GLOBOCAN 2008 (Ferlay et al, 2010). The expected number of pancreatic cancers was calculated by multiplying each age-standardised incidence rate of the country-specific general population by the observed person-years in our BRCA cohort and divided by 100 000 to get the expected numbers of pancreatic cancers (indirect standardisation method). The SIRs were also estimated for age subgroups <65 years and ⩾65 years. We divided the cohort of women into those with and without a first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer and into those who did and who did not develop pancreatic cancer during the follow-up period. We then estimated the univariate odds ratio for the development of pancreatic cancer, conditional on the presence of a first-degree relative affected with pancreatic cancer, based on the two by two table.

Overall survival

In a separate analysis, we reviewed the pedigrees of all families in the database with a BRCA1 or a BRCA2 mutation. This included 8140 pedigrees from families with a known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, enrolled at one of 50 centres across North America and Europe. Families were ascertained on the basis of breast and ovarian cancers (but not pancreatic cancer); we then identified families with one or more individuals with pancreatic cancer. The pancreatic cancer subjects were included if they were a first-, second- or third-degree relative of a known carrier. A total of 351 pancreatic cancers were identified. Of these, 163 were in first-degree relatives of a known carrier, 143 were in second-degree relatives and 45 were in third-degree relatives. We recorded the age at diagnosis and age at death for each case, from the information provided on the pedigree diagram, where available. We did not have the mutation status of these patients and the diagnosis was based on information provided by the proband at interview, when the pedigree was constructed. All cases of pancreatic cancer that were included in this analysis were diagnosed before the date of genetic testing of the proband, but the specific years of diagnosis were not indicated. To estimate survival, patients were followed from the year of diagnosis to the years of death or the year the pedigree was constructed. The survival from the diagnosis was calculated by Kaplan–Meier method and the difference between groups was compared with the log-rank test of significance. We did not have information on the specific cause of death for the pancreatic cancer patients, and all deaths were assumed to be from pancreatic cancer.

Results

Incidence

Five thousand eighty-nine women in our database of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers were followed for a mean of 1.95 years. We identified eight new pancreatic cancer cases among the BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers vs 3.28 pancreatic cancers expected (SIR=2.44, P=0.03). The characteristics of the eight incident cases are presented in Table 1. Six of the eight cases were confirmed by pathology report or medical record and two were based on the patient questionnaire. Of the eight pancreatic cancer cases, six cases occurred in BRCA1 carriers, vs 2.35 pancreatic cancers expected (SIR=2.52, P=0.04) and two cases occurred in BRCA2 carriers vs 0.94 pancreatic cancers expected (SIR=2.13, P=0.3) (Table 2). All eight pancreatic cancer cases were diagnosed in women aged 50 and above. For women above the age of 50, the annual incidence rate was 37 per 100 000 per year for BRCA1 carriers and 39 per 100 000 per year for BRCA2 carriers. The rates are estimated for women below and above age 65 in Table 3.

Interestingly, two of the incident case of pancreatic cancer had a first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer. Among the 5089 women in the follow-up study, 35 had a first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer (data for 615 women was missing). The odds ratio for developing pancreatic cancer for those with a first-degree relative was 46.5 (95% CI=9.4–230, P<0.0001), compared with women without a first-degree relative.

Survival

Of 8140 families in the database, a total of 317 (3.9%) families had one or more individuals diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Of 5742 families with a BRCA1 mutation, 213 (3.7%) had a case of pancreatic cancer, and of 2269 families with a BRCA2 mutation, 138 (6.1%) had a case of pancreatic cancer. In aggregate, 317 families included 351 subjects with pancreatic cancer (range 1–5). The mean age at diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was similar in cases from families with a BRCA1 and a BRCA2 mutation (BRCA1=63.4 years, range 20–90 years; BRCA2=62.7 years, range 27–90 years; P=0.56). Of the 351 cases of pancreatic cancer, 84% were diagnosed at age 50 or above (87% for BRCA1 carriers and 80% for BRCA2 carriers). Of the 351 cases of pancreatic cancer 203 (58%) were in males and 148 (42%) were in females.

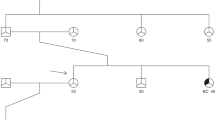

The mean survival from diagnosis to death was 1.07 years (range 0.5–6 years) for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 1.00 years (range 0.5–6 years) for BRCA2 mutation carriers (P=0.83). The 5-year survival rate was 6.1% for cases with a BRCA1 mutation and 3.6% for cases with a BRCA2 mutation (Figure 1). We did not observe a significant survival difference between males and females among either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers (data not shown).

Discussion

In the prospective component of this study of BRCA1 and the BRCA2 mutation carriers, we saw a statistically significant 2.4-fold increase in the incidence of pancreatic cancer in female BRCA mutation carriers (P=0.03). The increase in the incidence of pancreatic cancer was similar for BRCA1 mutation carriers (SIR=2.55) and BRCA2 mutation carriers (SIR=2.13). For women above the age of 50, the annual risk of pancreatic cancer for a woman with a mutation in either gene was 0.04%. In this prospective study, we do not have data on males with either mutation. However, based on the sex distribution of pancreatic cases in our pedigree review (203 males: 148 females), we expect the risk of pancreatic cancer to be slightly higher in males.

In our study, the absolute risks of pancreatic cancer were similar for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers; in other studies, the risks for BRCA2 carriers exceeded that for BRCA1 carriers. In particular, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (BCLC) reported a 2.2-fold increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer among BRCA1 mutation carriers (P=0.004) (Thompson et al, 2002) and a 3.5-fold increase in the risk of pancreatic cancer was reported in the BRCA2 carriers (P=0.0012) (The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1999).

We measured survival in the pancreatic patients recorded in the pedigrees for the families in the data set. We did not have the mutation status of the cancers observed in relatives and a proportion of these will likely not carry the familial BRCA mutation. We observed a poor overall survival in both men and women with a BRCA1 mutation or a BRCA2 mutation. The average time from diagnosis to death was ∼1 year for both groups and the 5-year survival was 5% for BRCA1 carriers and 4% for BRCA2 carriers. The poor survival in our cohort is similar to that of the general population, where the 5-year survival is 6% (Canadian Cancer Society, 2010).

Our study has a number of limitations pertaining to both the estimation of the incidence and overall survival. Our cohort study includes only women and therefore we cannot estimate the incidence of pancreatic cancer in males. The number of incidence cases was relatively small (eight) and this limits the precision of the risk estimates, especially for subgroups. To record overall survival, we obtained the age of diagnosis and death on the patients with pancreatic cancer from the review of family pedigrees based on the probands interview. Moreover, it was not possible to review the pathology reports to confirm the diagnosis in the relatives. Some patients may have died of causes other than the pancreatic cancer, but this number is likely to be small.

Our study has implications for the planning of a screening programme for pancreatic cancer in men and women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. The estimated annual incidence rate for women over the age of 50 was 0.04% for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, and the results of our study do not support the adoption of a screening policy (if we were to screen 1000 carriers annually for 10 years, we would expect to detect approximately four pancreatic cancers). Among women with a mutation and a first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer the risk was much higher (annual risk=1.0%). The high relative risk for women with a family history was based on only two incident cases (one with a mutation in BRCA1 and one in BRCA2) and the confidence limits are wide. However, this observation suggests that there may be modifying genes associated with the development of pancreatic cancer in these families. Furthermore, it has not yet been shown that screening for pancreatic cancer is associated with a reduction in mortality from the disease and screening should not be recommended outside of clinical trials.

The poor survival observed among pancreatic cancer patients in these families does not appear to be different from that of patients in the general population and emphasises the need for better prevention strategies and novel chemotherapies. It is possible that some drugs (e.g., cisplatinum) might potentially benefit specifically BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers diagnosed with pancreatic cancer (van der Heijden et al, 2005; Lowery et al, 2011) and clinical trials are indicated.

Change history

04 December 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bartsch DK, Kress R, Sina-Frey M, Grutzmann R, Gerdes B, Pilarsky C et al (2004) Prevalence of familial pancreatic cancer in Germany. Int J Cancer 110: 902–906

Caldas C, Hahn SA, da Costa LT, Redston MS, Schutte M, Seymour AB, Weinstein CL, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ, Kern SE (1994) Frequent somatic mutations and homozygous deletions of the p16 (MTS1) gene in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 8: 27–32

Canadian Cancer Society (2010) Canadian Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Society: Toronto

Ghiorzo P, Fornarini G, Sciallero S, Battistuzzi L, Belli F, Bernard L, Bonelli L, Borgonovo G, Bruno W, De Cian F, Decensi A, Filauro M, Faravelli F, Gozza A, Gargiulo S, Mariette F, Nasti S, Pastorino L, Queirolo P, Savarino V, Varesco L, Scarrà GB Genoa Pancreatic Cancer Study Group (2012) CDKN2A is the main susceptibility gene in Italian pancreatic cancer families. J Med Genet 49: 164–170

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2 cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 (Internet). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; available from http://globocan.iarc.fr

Fernandez E, La Vecchia C, D’Avanzo B, Negri E, Franceschi S (1994) Family history and the risk of liver, gallbladder, and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 3: 209–212

Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE (1996) DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science 271: 350–353

Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, Borges M, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Palmisano E, Brune K, Jaffee EM, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Parmigiani G, Kern SE, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Eshleman JR, Goggins M, Klein AP (2009) Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science 324: 217

Klein AP, Hruban RH, Brune KA, Petersen GM, Goggins M (2001) Familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer J 7: 266–273

Lal G, Liu G, Schmocker B, Kaurah P, Ozcelik H, Narod SA, Redston M, Gallinger S (2000) Inherited predisposition to pancreatic adenocarcinoma: role of family history and germ-line p16, BRCA1, and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Res 60: 409–416

Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK, Yu KH, Janjigian YY, Ludwig E, D'Adamo DR, Salo-Mullen E, Robson ME, Allen PJ, Kurtz RC, O'Reilly EM (2011) An emerging entity: pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. Oncologist 16: 1397–1402

Phelan CM, Lancaster JM, Tonin P, Gumbs C, Cochran C, Carter R, Ghadirian P, Perret C, Moslehi R, Dion F, Faucher MC, Dole K, Karimi S, Foulkes W, Lounis H, Warner E, Goss P, Anderson D, Larsson C, Narod SA, Futreal PA (1996) Mutation analysis of the BRCA2 gene in 49 site-specific breast cancer families. Nat Genet 13: 120–122

Redston MS, Caldas C, Seymour AB, Hruban RH, da Costa L, Yeo CJ, Kern SE (1994) p53 mutations in pancreatic carcinoma and evidence of common involvement of homocopolymer tracts in DNA microdeletions. Cancer Res 54: 3025–3033

Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DEC, Rosen B, Bradley L, Fan I, Ang J, Li S, Zhang S, Shaw PA, Narod SA (2006) Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 1694–1706

Roberts NJ, Jiao Y, Yu J, Kopelovich L, Petersen GM, Bondy ML, Gallinger S, Schwartz AG, Syngal S, Cote ML, Axilbund J, Schulick R, Ali SZ, Eshleman JR, Velculescu VE, Goggins M, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Hruban RH, Kinzler KW, Klein AP (2011) ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov 2: 41–46

Sato N, Rosty C, Jansen M, Fukushima N, Ueki T, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Hruban RH, Goggins M (2001) STK11/LKB1 Peutz-Jeghers gene inactivation in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Pathol 159: 2017–2022

The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (1999) Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 1310–1316

Thompson D, Easton DF Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (2002) Cancer Incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 1358–1365

van der Heijden MS, Brody JR, Dezentje DA, Gallmeier E, Cunningham SC, Swartz MJ, DeMarzo AM, Offerhaus GJ, Isacoff WH, Hruban RH, Kern SE (2005) In vivo therapeutic responses contingent on Fanconi anemia/BRCA2 status of the tumor. Clin Cancer Res 11: 7508–7515

Win AK, Young JP, Lindor NM, Tucker KM, Ahnen DJ, Young GP, Buchanan DD, Clendenning M, Giles GG, Winship I, Macrae FA, Goldblatt J, Southey MC, Arnold J, Thibodeau SN, Gunawardena SR, Bapat B, Baron JA, Casey G, Gallinger S, Le Marchand L, Newcomb PA, Haile RW, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA (2012) Colorectal and other cancer risks for carriers and noncarriers from families with a DNA mismatch repair gene mutation: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 30: 958–964

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Appendix

Appendix

Other members of the Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group: Ophira Ginsburg, André Robidoux, Louise Maehle, Kevin Sweet, Dawna Gilchrist, Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, Fergus Couch, Claudine Isaacs, Beth Karlan, Charis Eng, Jeffrey N. Weitzel, Mary B. Daly, Judy E. Garber, Dana Zakalik, Carey A. Cullinane, Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet, Howard Saal, Wendy Meschino, Wendy McKinnon, Marie Wood, Taya Fallen, Raluca Kurz, Siranoush Manoukian, Barry Rosen, Rochelle Demsky, Edmond Lemire, Jane Mclennan, Seema Panchal, Albert E. Chudley, Susan T. Vadaparampil, Tuya Pal, Daniel Rayson, Adriana Valentini, Susan Friedman (on behalf of FORCE) Cezary Cybulski, Jacek Gronwald, Tomasz Byrski, Tomasz Huzarski.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, J., Ragone, A., Lubinski, J. et al. The incidence of pancreatic cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Br J Cancer 107, 2005–2009 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.483

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.483

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Current status of inherited pancreatic cancer

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2022)

-

Recurrent PALB2 mutations and the risk of cancers of bladder or kidney in Polish population

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2021)

-

BRCA-mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

British Journal of Cancer (2021)

-

Cell death in pancreatic cancer: from pathogenesis to therapy

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology (2021)

-

The genetics of ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas in the year 2020: dramatic progress, but far to go

Modern Pathology (2020)