Abstract

Background:

Bevacizumab improves outcome for most recurrent glioblastoma patients, but the duration of benefit is limited and survival after initial bevacizumab progression is poor. We evaluated bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression among recurrent glioblastoma patients as it is a common, yet unsupported practice in some countries.

Methods:

We analysed outcome among all patients (n=99) who received subsequent therapy after progression on one of five consecutive, single-arm, phase II clinical trials evaluating bevacizumab regimens for recurrent glioblastoma. Of note, the five trials contained similar eligibility, treatment and assessment criteria, and achieved comparable outcome.

Results:

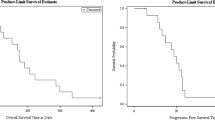

The median overall survival (OS) and OS at 6 months for patients who continued bevacizumab therapy (n=55) were 5.9 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.4, 7.6) and 49.2% (95% CI: 35.2, 61.8), compared with 4.0 months (95% CI: 2.1, 5.4) and 29.5% (95% CI: 17.0, 43.2) for patients treated with a non-bevacizumab regimen (n=44; P=0.014). Bevacizumab continuation was an independent predictor of improved OS (hazard ratio=0.64; P=0.04).

Conclusion:

The results of our retrospective pooled analysis suggest that bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression modestly improves survival compared with available non-bevacizumab therapy for recurrent glioblastoma patients require evaluation in an appropriately randomised, prospective trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Anti-angiogenic agents inhibit key mediators of tumour blood vessel development and currently represent a major class of therapeutics broadly utilised in many oncology settings. Although these agents often significantly improve radiographic response and progression-free survival (PFS) rates, overall survival (OS) benefit has been modest for many patients.

Bevacizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF, received accelerated approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for recurrent glioblastoma based on radiographic response rates of 28–35% (Cohen et al, 2009). In addition, 6-month PFS-6 in these studies was 29–43%, however, median OS was only 7.8–9.2 months (Friedman et al, 2009; Kreisl et al, 2009). Of note, these data were judged insufficient for approval by the European Medicinal Agency. Currently, two randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trials are evaluating bevacizumab among newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients.

Essentially all recurrent glioblastoma patients ultimately progress following bevacizumab therapy and to date, no effective therapy has been identified following bevacizumab progression (Norden et al, 2008; Iwamoto et al, 2009; Kreisl et al, 2009; Quant et al, 2009; Torcuator et al, 2009; Lu-Emerson et al, 2011; Reardon et al, 2011). Primarily because there is no effective therapy, many US oncologists currently continue bevacizumab and either add or switch chemotherapy upon bevacizumab progression. Although growing data support bevacizumab continuation among colorectal cancer patients (Grothey et al, 2008; Cohn et al, 2010), no data support this practice for glioblastoma patients at present. We therefore examined outcome of bevacizumab continuation compared with non-bevacizumab therapy among patients treated on all completed bevacizumab-based clinical trials conducted at our institution for recurrent glioblastoma patients. Importantly, the population for this pooled analysis was relatively homogeneous owing to consistent eligibility criteria, treatment guidelines and evaluation parameters across our phase II bevacizumab trials. In addition, patient characteristics as well as outcome on study and after study discontinuation were comparable across the studies.

Materials and methods

Objectives

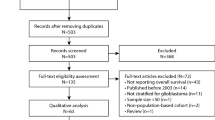

We performed a pooled analysis of all completed clinical trials (n=5) evaluating bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma patients performed at our institution over the past 5 years (Vredenburgh et al, 2007; Reardon et al, 2009; Sathornsumetee et al, 2010; Desjardins et al, 2012). The primary objective was to assess outcome after bevacizumab progression and determine whether any type of therapy, including bevacizumab continuation, altered outcome.

Participants

All patients treated at the Duke University Medical Center on one of five consecutive, IRB-approved, single-arm, phase II, bevacizumab trials for recurrent glioblastoma between July 2005 and July 2010 were included (Table 1). Entry criteria across the studies were similar and included histopathological confirmation of grade IV malignant glioma, recurrent disease following standard temozolomide-based chemoradiotherapy (Stupp et al, 2005), up to three prior episodes of progressive disease, age ⩾18 years, Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ⩾60, and adequate renal, hepatic and haematologic function. Patients were excluded from these studies if they received prior bevacizumab, were on therapeutic anti-coagulation, or had grade >1 haemorrhage on baseline brain MRI.

Description of procedures or investigations undertaken

In phase II bevacizumab clinical trial, patients underwent physical examination and contrast-enhanced neuroimaging within 14 days of starting study therapy and then every 2 months for 2 years. Thereafter, assessments were performed quarterly for 2 years, and then semi-annually. Response assessment incorporated clinical and MRI examinations, the latter included evaluation of both enhancing and T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences as described by Radiologic Assessment in Neuro-Oncology criteria (Wen et al, 2010). Dose modification and re-treatment guidelines as well as study discontinuation parameters were similar across the studies. Each bevacizumab trial included a single-stage design with a primary endpoint of PFS-6 as well as early termination rules for either excessive toxicity or poor outcome.

In each trial, bevacizumab was combined with a partner therapeutic that was administered according to previously determined guidelines including irinotecan (Friedman et al, 1999), daily temozolomide (Perry et al, 2010), bortezomib (Phuphanich et al, 2010), oral etoposide (Kesari et al, 2007) or erlotinib (van den Bent et al, 2009). Bevacizumab was administered at 10 mg kg−1 every 2 weeks in each therapeutic study except for the bortezomib study where it was administered at 15 mg kg−1 every 3 weeks. Study therapy was planned to continue for 12 months or until progressive disease, excessive toxicity or non-compliance.

Following discontinuation of bevacizumab study therapy, subsequent treatment options including additional anti-tumour therapy or palliative care/hospice were reviewed with each patient/caregiver. For those who elected additional anti-tumour therapy, the specific choice of subsequent treatment after bevacizumab study discontinuation was made solely by the treating oncologist in consultation with the patient and their respective caregivers. There were no formal or informal guidelines, algorithm or protocol to address treatment selection following initial bevacizumab progression. Subsequent treatment and associated evaluations were performed either locally or at our institution depending on patient preference. All subsequent treatments were tabulated and the time to progression for the first subsequent treatment after bevacizumab discontinuation was assessed for each patient. All patients were followed for OS.

Ethics

All patients included in this analysis provided informed consent to participate in the phase II bevacizumab clinical trials. In addition, this pooled analysis, as well as the five associated therapeutic studies, were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Statistical methods

Two-sample t-tests, two-sample Wilcoxon’s tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the characteristics of patients who received bevacizumab and non-bevacizumab as therapy following progression on bevacizumab treatment.

Among patients who received subsequent therapy, OS was defined as the time between initiation of treatment after bevacizumab study discontinuation and death or last follow-up for surviving patients, and PFS was defined as the time between initiation of treatment after bevacizumab study discontinuation and first occurrence of disease progression or death. The Kaplan–Meier estimator was used to describe the distribution of OS and PFS among patient subgroups defined by various baseline clinical factors and subsequent therapy.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the individual and joint association of the following covariates with OS and PFS: age at subsequent treatment (⩽50 years; >50 years); KPS at progression on bevacizumab trial therapy (<90, ⩾90); specific bevacizumab trial therapy; number of prior disease progressions (⩽2, >2); time since initial diagnosis (⩽18 months, >18 months); duration of bevacizumab trial treatment (⩽6 months, >6 months); dexamethasone use at study progression; the specific type of subsequent treatment (bevacizumab or non-bevacizumab); whether patients received initial subsequent therapy or therapy evaluations at the study centre; proximity to the study centre (<200 miles vs ⩾200 miles); and residence in an urban environment. Backwards elimination with a 0.1 significance level was used to develop a parsimonious multivariate model.

Results

Initial bevacizumab study therapy

Patient characteristics were comparable across the five single-arm, phase II bevacizumab studies (Supplementary Table 1). Enrolled patients were moderately pre-treated with >50% at second or third progression, however, they were also relatively young (mean age=52.4 years) and 50% had a KPS of 90–100. Outcome varied, but was overall comparable across the studies. Approximately 15% of patients remained progression-free for 12 months and alive at 2 years (Table 1).

Treatment and outcome following bevacizumab trial progression

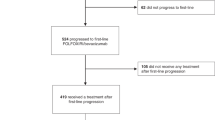

Among 140 patients who discontinued bevacizumab study therapy due to progressive disease, 99 (71%) received additional therapy whereas the remainder received palliative care (Figure 1). After discontinuation of initial bevacizumab therapy, the median survival of the 41 patients who received palliative care was 1.5 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.7, 2.1). Their survival was significantly worse than the survival of patients who received subsequent therapy (P<0.0001).

The remainder of the data presented in this manuscript focuses on the 99 patients who received subsequent therapy after progression on bevacizumab study therapy. Initial subsequent treatment for 55 patients (56%) included bevacizumab whereas 44 patients (44%) began non-bevacizumab therapy. Of note, clinical characteristics and treatment factors for patients who received bevacizumab continuation were comparable to those who received non-bevacizumab therapy (Table 2).

Table 3 summarises outcome after bevacizumab trial progression. Patients who continued bevacizumab therapy had a better PFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P=0.0138) than those who initiated non-bevacizumab therapy (Figures 2A and B).

Before assessing the impact of potential confounding factors on the effect of bevacizumab continuation within the context of a multivariate model, we explored the effect of individual baseline clinical factors on OS (Table 4A). Karnofsky performance status, dexamethasone use, subsequent treatment evaluations at Duke and bevacizumab continuation were associated with OS. Proximity to the study centre (<200 vs ⩾200 miles) and residence in an urban environment were not assessed as covariates due to lack of distribution with 87% of patients living >200 miles from the study centre and 83% not living in an urban environment. We also evaluated whether early (before July, 2007) or late (after July 2007) treatment affected outcome to assess for a potential time bias, but noted comparable outcomes for both time periods (Supplementary Table 2).

Multivariate analysis (Table 4B) revealed that continuation of bevacizumab therapy was an independent predictor of outcome (hazard ratio (HR): 0.0.64; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.98; P=0.04). Two other factors were also found to independently predict outcome in this analysis: dexamethasone use and treatment at the study centre. Both factors are thought to reflect tumour burden and growth. Specifically, patients requiring dexamethasone, a corticosteroid used to alleviate symptoms due to tumour-associated oedema, had a poorer outcome (HR: 2.43; 95%: 1.55, 3.38; P<0.0001). In addition, treatment at the study centre was associated with better outcome (HR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.31, 0.73; P=0.0006). The latter finding also likely reflects tumour burden because >80% of the study patients lived >200 miles from the study centre and travel to the study centre likely posed a greater hardship for more debilitated patients.

Discussion

Traditional oncology dogma argues against therapy continuation beyond progression. Nonetheless, emerging data suggest that there may be specific circumstances where re-evaluation of this long-held practice may be considered. Although underlying mechanisms of action are unclear, continuation of anti-angiogenic therapy following initial progression appears to be associated with improved outcome for some cancer patients. Interest in bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression initiated from intriguing preliminary data derived from two large observational cohort studies among metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Results from the Bevacizumab Regimens: Investigation of Treatment Effects and Safety (BRiTE) study demonstrated that patients who continued bevacizumab beyond first progression (n=642) had a median OS of 32 months compared with 20 months (P<0.01, HR 0.48) for patients treated with non-bevacizumab therapy (n=531).(Grothey et al, 2008) Similarly, in the ARIES study, patients who continued bevacizumab (n=408) achieved a median OS of 28 months compared with 19 months for those treated with alternative therapy (n=336; P<0.001; HR: 0.52; Cohn et al, 2010). Prospective validation of the BRiTE and ARIES studies is being pursued in ongoing randomised phase III studies, including the ML-18147 study (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00700102). Of note, a 26 January 2012 press release from the ML-18147 study sponsor indicated that this study had successfully met its primary endpoint of OS.

The outcome of glioblastoma patients who progress on bevacizumab therapy remains dismal. Owing to lack of effective therapeutic options, some US clinicians opt to continue bevacizumab, usually in combination with a chemotherapeutic agent, although no data currently support this practice. We therefore sought to evaluate outcome associated with bevacizumab continuation in comparison with non-bevacizumab therapy after initial bevacizumab progression among a homogeneous cohort of recurrent glioblastoma patients pooled from five consecutive single-arm phase II studies.

We noted that bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression was associated with modestly improved outcome compared with non-bevacizumab therapy. Although overall outcome for all patients after bevacizumab progression was poor, continuation of bevacizumab was associated with improved PFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P=0.0138). Furthermore, multivariate analysis identified bevacizumab continuation as a significant predictor of improved outcome (P=0.04).

Our study findings confirm that recurrent glioblastoma patients who progress on bevacizumab respond poorly to subsequent therapy, regardless of whether bevacizumab is continued. Of note, median OS for patients who continued bevacizumab in our series exceeded that reported in some prior reports. Several factors may have contributed to these discrepant results. Patients in our series had similar characteristics, and underwent consistent treatment, follow-up and evaluation regimens. In contrast, most prior reports derive primarily from retrospective series of patients with varied characteristics and treatment regimens, although two small prospective single-arm studies have also been reported (Norden et al, 2008; Iwamoto et al, 2009; Kreisl et al, 2009; Quant et al, 2009; Torcuator et al, 2010; Reardon et al, 2011). Importantly, none of the prior studies included a control group of bevacizumab failing patients treated with non-bevacizumab therapy. Thus, our results reflect the only analysis in the literature that includes comparable cohorts of patients treated with bevacizumab and non-bevacizumab regimens beyond initial bevacizumab progression.

Potential mechanisms underlying a modest survival benefit from bevacizumab beyond initial progression remain unclear. Research to determine underlying mechanisms as well as biomarkers to predict further therapeutic benefit are critically needed. One possible mechanism for glioblastoma patients relates to the potent anti-permeability effect of bevacizumab on tumour vasculature. Accordingly, it is possible that a survival benefit from bevacizumab continuation may be due to diminished tumour-associated oedema and mass effect rather than direct anti-tumour activity, as has been suggested in some preclinical models (Kamoun et al, 2009). Comprehensive MRI assessments upon bevacizumab progression in future studies, including diffusion and perfusion sequences, may help address this possibility.

There are several limitations associated with our study. First, we used a retrospective analysis, which is subject to inherent definable as well as undefinable biases. We attempted to adjust comparisons of outcome associated with bevacizumab and non-bevacizumab therapy for potential confounding factors, including factors related to treatment selection. Strengths of our pooled analysis include the relative homogeneity of included patients and the overall similarity between those who continued bevacizumab compared with those treated with non-bevacizumab therapy following initial bevacizumab progression. In addition, although there were no formal or informal guidelines for treatment choice following initial bevacizumab progression, the individualised, patient-centric approach to select therapy following initial bevacizumab progression for patients evaluated in this analysis reflects actual current ‘real-world’ practice in many centres, particularly in the United States. Nonetheless, it is possible that unaccounted factors may have impacted the choice of subsequent therapy made by treating oncologists which in turn may have biased outcome for patients receiving bevacizumab continuation. For this reason, it is imperative that our study findings be prospectively evaluated in an appropriately controlled, randomised clinical trial.

Second, although chemotherapy may have influenced outcome among patients treated in our analysis, this possibility is unlikely because the same chemotherapy agents were administered to both groups of patients. Our study design also precluded determination of whether bevacizumab alone was responsible for improved outcome as none of the patients received single-agent bevacizumab therapy after initial bevacizumab trial progression.

Third, our analysis focused on outcome after the first regimen following bevacizumab study therapy. Although it is possible that additional therapies beyond the first regimen may have impacted overall outcome, a steep decrease in number of patients who received more than an initial regimen precluded such an analysis.

Fourth, our study evaluated recurrent patients, thus a separate study is required to determine whether bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression will impact outcome for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients treated with bevacizumab. In addition, it is unclear whether continuation of alternative anti-angiogenic agents, such as other monoclonal antibodies or tyrosine kinase inhibitors, can improve outcome following initial bevacizumab progression.

Fifth, glioblastoma patients included in our analysis had favourable prognostic features including young age and good performance status. Therefore, our findings may not be applicable to the overall recurrent glioblastoma population. Finally, our analysis did not assess patient function or quality of life while receiving therapy after bevacizumab progression. Given the overall poor outcome of glioblastoma patients after progression on bevacizumab, future studies to evaluate therapeutic interventions for such patients should prioritise assessment of quality of life and patient function.

In conclusion, there is growing interest in evaluating bevacizumab continuation beyond progression for oncology patients who derive benefit from initial bevacizumab-based therapy. Our retrospective pooled analysis suggests that bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression provides a modest survival benefit compared with available non-bevacizumab therapies for recurrent glioblastoma patients. Although we attempted to control for as many biases as possible, the retrospective design of our study presents inherent limitations. Therefore, we conclude that the role of bevacizumab continuation beyond initial progression requires prospective evaluation in an appropriately randomised clinical trial. Future studies should also aim to improve understanding of underlying mechanisms of action as well as identify biomarkers predictive of outcome. Most importantly, our overall results highlight the dismal outcome of glioblastoma patients who progress on bevacizumab and the critical need to develop effective therapies for these patients.

Change history

11 October 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Cohn AL, Bekaii-Saab TS, Bendell JC, Hurwitz H, Kozloff M, Roach N, Tezcan H, Feng S, Sing AP, Grothey A (2010) Clinical outcomes in bevacizumab (BV) treated patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): results from ARIES observational cohort study (OCS) and confirmation of BRiTE data beyond progression (BBP). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 28: 284s (abstract # 3596)

Cohen MH, Shen YL, Keegan P, Pazdur R (2009) FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab (Avastin) as treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Oncologist 14 (11): 1131–1138

Desjardins A, Reardon DA, Coan A, Marcello J, Herndon JE, Bailey L, Peters KB, Friedman HS, Vredenburgh JJ (2012) Bevacizumab and daily temozolomide for recurrent glioblastoma. Cancer 118: 1302–1312

Friedman HS, Petros WP, Friedman AH, Schaaf LJ, Kerby T, Lawyer J, Parry M, Houghton PJ, Lovell S, Rasheed K, Cloughsey T, Stewart ES, Colvin OM, Provenzale JM, McLendon RE, Bigner DD, Cokgor I, Haglund M, Rich J, Ashley D, Malczyn J, Elfring GL, Miller LL (1999) Irinotecan therapy in adults with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1516–1525

Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, Yung WK, Paleologos N, Nicholas MK, Jensen R, Vredenburgh J, Huang J, Zheng M, Cloughesy T (2009) Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 27 (28): 4733–4740

Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, Dong W, Sargent D, Hedrick E, Kozloff M (2008) Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE). J Clin Oncol 26 (33): 5326–5334

Iwamoto FM, Abrey LE, Beal K, Gutin PH, Rosenblum MK, Reuter VE, DeAngelis LM, Lassman AB (2009) Patterns of relapse and prognosis after bevacizumab failure in recurrent glioblastoma. Neurology 73 (15): 1200–1206

Kamoun WS, Ley CD, Farrar CT, Duyverman AM, Lahdenranta J, Lacorre DA, Batchelor TT, di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Munn LL, Fukumura D, Sorensen AG, Jain RK (2009) Edema control by cediranib, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-targeted kinase inhibitor, prolongs survival despite persistent brain tumor growth in mice. J Clin Oncol 27 (15): 2542–2552

Kesari S, Schiff D, Doherty L, Gigas DC, Batchelor TT, Muzikansky A, O'Neill A, Drappatz J, Chen-Plotkin AS, Ramakrishna N, Weiss SE, Levy B, Bradshaw J, Kracher J, Laforme A, Black PM, Folkman J, Kieran M, Wen PY (2007) Phase II study of metronomic chemotherapy for recurrent malignant gliomas in adults. Neuro Oncol 9 (3): 354–363

Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, Stroud I, Garren N, Mackey M, Butman JA, Camphausen K, Park J, Albert PS, Fine HA (2009) Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 27 (5): 740–745

Lu-Emerson C, Norden AD, Drappatz J, Quant EC, Beroukhim R, Ciampa AS, Doherty LM, Lafrankie DC, Ruland S, Wen PY (2011) Retrospective study of dasatinib for recurrent glioblastoma after bevacizumab failure. J Neurooncol 104 (1): 287–291

Norden AD, Young GS, Setayesh K, Muzikansky A, Klufas R, Ross GL, Ciampa AS, Ebbeling LG, Levy B, Drappatz J, Kesari S, Wen PY (2008) Bevacizumab for recurrent malignant gliomas: efficacy, toxicity, and patterns of recurrence. Neurology 70 (10): 779–787

Perry JR, Belanger K, Mason WP, Fulton D, Kavan P, Easaw J, Shields C, Kirby S, Macdonald DR, Eisenstat DD, Thiessen B, Forsyth P, Pouliot JF (2010) Phase II trial of continuous dose-intense temozolomide in recurrent malignant glioma: RESCUE study. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 2051–2057

Phuphanich S, Supko JG, Carson KA, Grossman SA, Burt Nabors L, Mikkelsen T, Lesser G, Rosenfeld S, Desideri S, Olson JJ (2010) Phase 1 clinical trial of bortezomib in adults with recurrent malignant glioma. J Neurooncol 100 (1): 95–103

Quant EC, Norden AD, Drappatz J, Muzikansky A, Doherty L, Lafrankie D, Ciampa A, Kesari S, Wen PY (2009) Role of a second chemotherapy in recurrent malignant glioma patients who progress on bevacizumab. Neuro Oncol 11 (5): 550–555

Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Peters K, Gururangan S, Sampson J, Rich JN, McLendon R, Herndon JE, Marcello J, Threatt S, Friedman AH, Vredenburgh JJ, Friedman HS (2011) Phase II study of metronomic chemotherapy with bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma after progression on bevacizumab therapy. J Neurooncol 103 (2): 371–379

Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Gururangan S, Sampson JH, Sathornsumetee S, McLendon RE, Herndon JE, Marcello JE, Norfleet J, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Friedman HS (2009) Metronomic chemotherapy with daily, oral etoposide plus bevacizumab for recurrent malignant glioma: a phase II study. Br J Cancer 101 (12): 1986–1994

Sathornsumetee S, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, McLendon RE, Marcello J, Herndon JE, Mathe A, Hamilton M, Rich JN, Norfleet JA, Gururangan S, Friedman HS, Reardon DA (2010) Phase II trial of bevacizumab and erlotinib in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol 12 (12): 1300–1310

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352 (10): 987–996

Torcuator R, Zuniga R, Mohan YS, Rock J, Doyle T, Anderson J, Gutierrez J, Ryu S, Jain R, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T (2009) Initial experience with bevacizumab treatment for biopsy confirmed cerebral radiation necrosis. J Neurooncol 94 (1): 63–68

Torcuator RG, Thind R, Patel M, Mohan YS, Anderson J, Doyle T, Ryu S, Jain R, Schultz L, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T (2010) The role of salvage reirradiation for malignant gliomas that progress on bevacizumab. J Neurooncol 97 (3): 401–407

van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Rampling R, Kouwenhoven MC, Kros JM, Carpentier AF, Clement PM, Frenay M, Campone M, Baurain JF, Armand JP, Taphoorn MJ, Tosoni A, Kletzl H, Klughammer B, Lacombe D, Gorlia T (2009) Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib versus temozolomide or carmustine in recurrent glioblastoma: EORTC brain tumor group study 26034. J Clin Oncol 27 (8): 1268–1274

Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, Marcello J, Reardon DA, Quinn JA, Rich JN, Sathornsumetee S, Gururangan S, Sampson J, Wagner M, Bailey L, Bigner DD, Friedman AH, Friedman HS (2007) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol 25 (30): 4722–4729

Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, Degroot J, Wick W, Gilbert MR, Lassman AB, Tsien C, Mikkelsen T, Wong ET, Chamberlain MC, Stupp R, Lamborn KR, Vogelbaum MA, van den Bent MJ, Chang SM (2010) Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol 28 (11): 1963–1972

Acknowledgements

We thank Wendy Gentry for her excellent secretarial support in the development of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants 5P50-NS-20023 and 5 R37 CA11898; National Institutes of Health Grant MO1 RR 30. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conception and design: DAR, JEH; collection and assembly of data: DAR, AD, KBP, JHS, ESL, ALS, EL, ST, SS, JNR, STB, HSF and JJV; data analysis and interpretation: DAR, JEH, DDB, JHS, AHF, JJV and AC; financial support: DDB; administrative support: DDB; provision of study material or patients: DAR, JJV, AD, KBP, JNR, JHS, HSF, SS, EL, ALS, ST and ESL; manuscript writing: DAR, JEH, KBP, AD, AC, EL, ALS, ST, ESL, SS, JNR, JHS, AHF, STB, DDB, HSF and JJV; final approval of manuscript: DAR, JEH, KBP, AD, AC, EL, ALS, ST, ESL, SS, JNR, JHS, AHF, STB, DDB, HSF and JJV.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JEH, KBP, AD, AC, EL, ALS, ST, ESL, SS, JHS, AHF, STB and DDB declare no conflict of interest. JNR received financial compensation from Genentech/Roche for Speakers Bureau participation and consultation, respectively. DAR, HSF and JJV received financial compensation from Genentech/Roche for Speakers Bureau participation and consultation.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Reardon, D., Herndon, J., Peters, K. et al. Bevacizumab continuation beyond initial bevacizumab progression among recurrent glioblastoma patients. Br J Cancer 107, 1481–1487 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.415

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.415

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Re-irradiation combined with bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma beyond bevacizumab failure: survival outcomes and prognostic factors

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Endoglin inhibitor TRC105 with or without bevacizumab for bevacizumab-refractory glioblastoma (ENDOT): a multicenter phase II trial

Communications Medicine (2023)

-

Assessment of tumor hypoxia and perfusion in recurrent glioblastoma following bevacizumab failure using MRI and 18F-FMISO PET

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Phase 2 trial of hypoxia activated evofosfamide (TH302) for treatment of recurrent bevacizumab-refractory glioblastoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Long-term survival in patients with recurrent glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab: a multicentric retrospective study

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2019)