Abstract

Background:

COIN compared first-line continuous chemotherapy with the same chemotherapy given intermittently or with cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer (aCRC).

Methods:

Choice between oxaliplatin/capecitabine (OxCap) and oxaliplatin/leucovorin (LV)/infusional 5-FU (OxFU) was by physician and patient choice and switching regimen was allowed. We compared OxCap with OxFU and OxCap+cetuximab with OxFU+cetuximab retrospectively in patients and examined efficacy, toxicity profiles and the effect of mild renal impairment.

Results:

In total, 64% of 2397 patients received OxCap(±cetuximab). Overall survival, progression free survival and overall response rate were similar between OxCap and OxFU but rate of radical surgeries was higher for OxFU. Progression free survival was longer for OxFU+cetuximab compared with OxCap+cetuximab but other efficacy measures were similar. Oxaliplatin/LV/infusional 5-FU (±cetuximab) was associated with more mucositis and infection whereas OxCap(±cetuximab) caused more gastrointestinal toxicities and palmar-plantar erythema. In total, 118 patients switched regimen, mainly due to toxicity; only 16% came off their second regimen due to intolerance. Patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) 50–80 ml min−1 on OxCap(±cetuximab) or OxFU+cetuximab had more dose modifications than those with better renal function.

Conclusions:

Overall, OxFU and OxCap are equally effective in treating aCRC. However, the toxicity profiles differ and switching from one regimen to the other for poor tolerance is a reasonable option. Patients with CrCl 50–80 ml min−1 on both regimens require close toxicity monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Intravenous (IV) 5-FU has been the backbone of treatment for advanced colorectal cancer (aCRC) for over 40 years. Currently capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine (Fp) prodrug, is commonly used as a convenient and effective alternative.

Two large phase III randomised trials compared capecitabine 1250 mg m−2 twice daily for 14 days repeated every 3 weeks to the Mayo Clinic regimen (Mayo) of IV leucovorin (LV) 20 mg m−2 followed by daily bolus 5-FU 425 mg m−2 for 5 days repeated every 4 weeks. Integrated data analysis of the two trials has shown similar overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) between the two regimens (Van Cutsem et al, 2004). In comparison with Mayo, capecitabine appeared to have a better toxicity profile and to be a safer treatment option for patients with moderate renal impairment. It was also shown that the standard starting dose of capecitabine was safe for patients with mild renal impairment; however, it was recommended that such patients should be monitored closely with prompt treatment interruption and dose reduction in the event of a grade 2 or higher toxicity (Cassidy et al, 2002).

Bolus 5-FU has largely been replaced with a continuous infusion in current treatment regimens. The de Gramont (LV5FU2) regimen of LV/infusional 5FU was compared with Mayo in a randomised trial. LV5FU2 was not only less toxic but was also associated with a better response rate (RR) and PFS (de Gramont et al, 1997).

Oxaliplatin is used in combination with either 5-FU (OxFU) or capecitabine (OxCap). Several phase III studies have compared OxFU with OxCap as first-line treatment for aCRC including: the German AIO (Porschen et al, 2007), the Spanish TTD (Diaz-Rubio et al, 2007), the international NO16966 (Cassidy et al, 2008) and the French FNCLCC (Ducreux et al, 2011). All four of these trials, together with two smaller ones, were included in a meta-analysis that showed similar PFS and OS but an inferior overall RR (ORR) for OxCap. Thrombocytopenia, diarrhoea and palmar-plantar erythema (PPE) were more prominent with OxCap-based regimens whereas neutropenia was more prominent with OxFU (Arkenau et al, 2008).

COIN is a three-arm multi-centre phase III open-label randomised controlled trial of the MRC, London. It compared standard continuous chemotherapy with OxFU or OxCap (Arm A) to each of two experimental arms: same chemotherapy plus cetuximab (Arm B) or intermittent chemotherapy without cetuximab (Arm C). The choice between OxFU and OxCap was nonrandomised but was agreed between the patient and treating clinician before randomisation. COIN did not meet either of its primary outcome measures as the addition of cetuximab was not associated with an improvement in efficacy (Maughan et al, 2011), and intermittent chemotherapy was not confirmed to be non-inferior to continuous treatment (Adams et al, 2011).

We report a retrospective analysis comparing OxCap with OxFU and OxCap+cetuximab with OxFU+cetuximab in terms of efficacy and severe side effects. We also examine the success of switching from one OxFp regimen to the alternate as a strategy for keeping patients on first-line treatment in case of intolerance to the first regimen chosen. Following the recommendation from Cassidy et al (2002) to monitor patients with mild renal impairment, we investigate the effect of renal impairment on toxicity on both OxFp regimens. None of these analyses were pre-specified in the COIN trial protocol.

Materials and methods

Patients

Accrual took place in 110 centres in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland between March 2005 and May 2008. Patients (age ⩾18) had: measurable metastatic or locally advanced colorectal adenocarcinoma; no previous chemotherapy for advanced disease; WHO performance status (PS) 0–2; adequate bone marrow, liver and kidney function. Patients were excluded if they had: CrCl<50 ml min−1; brain metastases; prior adjuvant treatment with oxaliplatin; uncontrolled medical co-morbidity; or were being considered for liver metastasectomy after initial down-staging chemotherapy.

Treatment plan

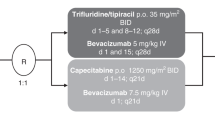

OxCap was given as per the XELOX regimen (3-weekly cycles of IV oxaliplatin 130 mg m−2 over 2 h on day 1 followed by capecitabine 1000 mg m−2 b.i.d. for 2 weeks). An analysis of the toxicity profile of the regimens after 800 patients had been randomised to the trial showed that the rate of severe diarrhoea for OxCap+cetuximab was excessive at 30% (Adams et al, 2009). Therefore, a protocol amendment in July 2007 mandated that the capecitabine dose in Arm B be reduced from 1000 to 850 mg m−2 b.i.d. for all future trial patients. Those already on trial had the choice to remain on the higher dose if well tolerated.

OxFU was a 2-weekly regimen of IV L-LV 175 or D,L-LV 350 mg given concurrently with oxaliplatin 85 mg m−2 over 2 h on day 1, followed by IV bolus 5-FU 400 mg m−2 and finally 5-FU 2400 mg m−2 infused over 46 h. This regimen requires an indwelling venous line (IVL) and is referred to as OxMdG in the United Kingdom.

Switching from one regimen to another was allowed for toxicity, compliance, logistics or patient’s choice. All patients switching from OxFU to OxCap had their dose of capecitabine reduced to 850 mg m−2 in the first cycle as the retained intracellular LV can potentially increase capecitabine toxicity (Hennig et al, 2008).

In Arm B, cetuximab was given in a loading dose of 400 mg m−2 IV over 2 h on day 1 and subsequently at 250 mg m−2 over 1 h once a week.

Response was assessed every 12 weeks using the RECIST 1.0 criteria. In both Arms A and B, treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicities or patient’s choice. In Arm C, treatment was stopped after 12 weeks and patients with responding or stable disease had a break from chemotherapy but this was restarted on evidence of clinical or radiological disease progression. An unlimited number of 12 week courses were allowed until evidence of treatment failure, which is defined as disease progression on or shortly after stopping treatment.

Renal function

Patients were required to have a baseline CrCl ⩾50 ml min−1 as estimated using the Cockcroft and Gault formula (Cockcroft and Gault, 1976). For the purpose of this analysis patients were divided into two CrCl groups: >80 and 50–80 ml min−1 corresponding to normal renal function and mild renal impairment, respectively. This is in line with the study by Cassidy et al (2002) in which the lower cut points for mild renal impairment and normal renal function were set at 51 and 81 ml min−1, respectively.

Efficacy outcome measures

The following outcome measures were compared: OS, PFS and RR at 12 weeks, ORR, and rate of radical surgeries (RRS). Overall RR is defined as the proportion of patients who had PR or CR while on treatment. Rate of radical surgeries is defined as the proportion of patients who had surgery to remove metastatic and/or primary disease with curative intent after starting trial treatment.

Toxicity

Toxicities were graded according to an increasing severity scale of 1–5 based on the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0. We compared the following ‘grade 3 or worse’ (G3+) toxicities between the two regimens: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, mucositis, lethargy, PPE, neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and treatment-related infection. The latter was defined as infection with G3/4 neutropenia or any IVL-related infection. Also, we compared rates of dose modification (reductions and delays) in the first 12 weeks of treatment.

Statistics

Arms A and C were combined for all analyses except PFS given the intermittent nature of treatment in Arm C. Comparisons were also made separately in each of Arms A, B and C. However, when looking at reasons for switching from one regimen to another, patients across all arms were combined to maximise power.

Patients were classified according to the chemotherapy regimen (OxCap or OxFU) used in their first cycle. Those who did not receive any trial treatment were excluded from all analyses and those who switched regimen were included in toxicity analyses for toxicities of the first regimen, but were excluded from all efficacy analyses.

OxCap was regarded as the control group for HR and OR calculations. Pearson’s χ2 tests were used to calculate P-values, and for cells with low count (n<5) Fisher’s exact test was used instead; P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method. Unadjusted and stratified HR was estimated using the Peto log-rank method, and OR using the Mantel–Haenszel method. For adjusted HR and OR, Cox and logistic regressions were used, respectively.

Efficacy and toxicity outcome measures were corrected for predefined prognostic factors (PFs), and whenever arms were combined correction was also made for trial arm membership.

Prognostic factors (PFs)

Prognostic factors for efficacy outcome measures were determined using a backward stepwise selection procedure, and was carried out separately for OS, PFS and ORR. There was a considerable overlap in PFs for each of these outcome measures. Therefore, the final set of PFs included those that appeared for any of the three outcomes: sex, white blood cell count, alkaline phosphatase level, the presence of tumour mutation in KRAS, BRAF or NRAS (all wild-type vs any mutant gene), WHO PS (0/1 vs 2), number of metastatic sites (0/1 vs 2) and synchronous vs metachronous metastases. Data on tumour mutation status were missing for some patients. To minimise the resulting loss of statistical power, multiple imputation was used when fitting models entering mutation status (Rubin, 1987). Where the outcome was time-to-event, the Nelson–Aalen estimator and event indicator were entered into the imputation model as suggested by White and Royston (2009). Both adjusted and unadjusted comparisons for efficacy outcome measures are presented hereafter.

PFs for toxicity were determined through the same procedure using the outcome ‘any G3+ toxicity vs none’. These were as follows: CrCl, age and WHO PS.

Results

Patients

See consort diagram (Figure 1). A total of 2445 patients were accrued between 2005 and 2008, of whom 2397 patients received at least one cycle of treatment. In all, 64% of patients received OxCap (±cetuximab) and 36% OxFU (±cetuximab). Tumour mutation status was unknown for 20% of patients. Baseline characteristics were largely balanced between the two regimens but patients on OxFU in each of Arm A and Arm B had higher cumulative dose of oxaliplatin compared with those on OxCap in each of the respective arm (Table 1). In all, 29% of patients on OxCap+cetuximab started on the reduced dose of capecitabine as per protocol amendment.

In total, 118 patients (5%) had a change in Fp regimen during trial treatment, 59 in each group corresponding to 4% and 7% of patients on OxCap (±cetuximab) and OxFU (±cetuximab), respectively. Reasons for switching regimen were (% out of patients who switched): IVL complications 0 (0%) and 42 (71%), toxicity (not further specified by centres) 45 (76%) and 6 (10%), and patient’s choice or compliance issues 13 (22%) and 10 (17%) of patients on OxCap (±cetuximab) and OxFU (±cetuximab), respectively; the reason was unknown for 1 patient in each group (2%). χ2 test for difference in distribution of reasons=72.2 on 2 degrees of freedom; P<0.001.

Although all patients who switched from OxCap (±cetuximab) remained on OxFU (±cetuximab) until they came off trial, 13 (22%) of those who switched from OxFU (±cetuximab) later returned to their original regimen after receiving, on average, two OxCap cycles. In most cases this was a temporary measure after the IVL was removed, due to a complication, to avoid treatment delays or the need for IVL re-insertion when patients in Arm C were about to go on a treatment break.

There was no excess of intolerance to the second regimen in patients who switched regimen once: 17 patients (16%) out of this group came off trial due to toxicity or patient’s choice compared with 436 (19%) of those who never switched (P=0.45).

Efficacy

Survival

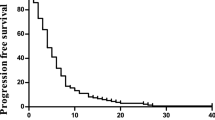

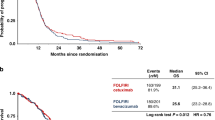

Overall, 2279 patients were included in the efficacy analyses after excluding those who switched regimen (Table 2 and Figures 2 and 3). Overall survival was similar for OxCap and OxFU with a median of 15.4 and 14.9 months, respectively; adjusted HR 0.92 (0.78, 1.09). Also, there was no difference in PFS: 7.4 and 8.8 months, respectively; adjusted HR 0.90 (0.77, 1.06).

OS was similar between OxCap+cetuximab and OxFU+cetuximab but PFS was longer for OxFU+cetuximab at 8.5 compared with 7.4 months for OxCap+cetuximab: adjusted HR 0.79 (0.67, 0.93). Progression free survival analysis was repeated using only patients who were randomised before capecitabine dose reduction was mandated for Arm B but the pattern stayed the same: adjusted HR 0.79 (0.65, 0.94), P=0.010.

Response and radical surgery

Response rate at 12 weeks and ORR were similar in each of the two comparisons: OxCap vs OxFU and OxCap+cetuximab vs OxFU+cetuximab.

Across all arms, 119 patients (5%) in the efficacy sample underwent radical surgery, of which 74% were liver metastasectomies, 13% lung metastasectomies, 9% primary resections (with or without liver metastasectomy) and 4% other sites. Rate of radical surgeries was higher for OxFU (6.5%) compared with OxCap (3.5%): adjusted OR 1.96 (1.18, 3.23) whereas RRS was similar between OxFU+cetuximab and OxCap+cetuximab.

Toxicity

Rate of ‘any G3+ toxicity’ was higher for OxFU at 64% compared with 57% for OxCap, P=0.008 (Table 3). However, after exclusion of asymptomatic neutropenia and thrombocytopenia rates became similar at 55% and 56%, respectively (P=0.84). Mucositis, neutropenia, treatment-related infections and neuropathy were significantly higher in the OxFU group with rates of 4%, 28%, 10% and 13% vs 1%, 3%, 1% and 10% for OxCap. Conversely, rates for nausea, diarrhoea and PPE were higher for OxCap at 8%, 16% and 4% vs 5%, 10% and 1% for OxFU. Dose reductions were more common for capecitabine, whereas dose delays were more common for OxFU. The differences in toxicity rates between OxFU+cetuximab and OxCap+cetuximab followed a similar pattern to those of OxFU vs OxCap. There was no difference in rates of treatment-related mortality in any of the analyses.

Toxicity and renal impairment

In the OxCap group, patients with CrCl 50–80 ml min−1 had higher rates of G3+ nausea (Table 4), diarrhea and thrombocytopenia compared with patients of CrCl >80 ml min−1: 11%, 19% and 4% compared with 5%, 11% and 1%, respectively. There was also a higher rate of dose delays: 49% compared with 38%, respectively.

In the OxFU group, there was no statistically significant difference for any of the toxicities or in dose modification between the two CrCl groups.

In the OxCap+cetuximab group, patients with CrCl 50–80 ml min−1 had a higher rate of G3+ lethargy (29% vs 17%) and more reductions in the capecitabine dose (67% vs 53%) compared with those of CrCl >80 ml min−1.

In the OxFU+cetuximab group, G3+ neutropenia was higher in patients with CrCl 50–80 ml min−1 compared with those of CrCl >80 ml min−1 (36% vs 23%) and so were the rates of dose delays (76% vs 66%) and reductions for both oxaliplatin (39% vs 26%) and 5-FU (56% vs 39%).

There was no difference in treatment-related deaths in any of the comparisons.

Discussion

This paper compared OxCap with OxFU given in the XELOX and OxMdG regimens, respectively. The latter regimen is widely used in the United Kingdom and is similar to FOLFOX6 (Braun et al, 2003). XELOX and FOLFOX6 were compared in the French study reported by Ducreux et al (2011), which showed in a per protocol analysis that XELOX is non-inferior to FOLFOX6 in terms of ORR (primary outcome measure), PFS and OS. Our retrospective analysis of the COIN data confirms that OxCap (XELOX) is equivalent to OxFU (OxMdG) in terms of the three efficacy measures, and is overall in line with the results of the meta-analysis by Arkenau et al (2008). However, the meta-analysis demonstrated an inferior ORR for OxCap (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.74–0.97). Both ORR and RRS in our study were numerically higher for OxFU; this reached statistical significance for RRS but not ORR despite the size of the study.

OxFU+cetuximab and OxCap+cetuximab were also equivalent in terms of OS, ORR and RRS. Nonetheless, PFS was longer for OxFU+cetuximab and this remained the case after repeating the analyses using only patients who were randomised before the protocol mandated capecitabine dose reduction. This observation is consistent with the positive interaction for cetuximab with the Fp partner in favour of 5-FU, which was demonstrated by the exploratory analyses of Arm B vs Arm A (Maughan et al, 2011). A possible explanation would be the higher toxicity for OxCap+cetuximab, which led to more dose reductions and a lower total dose of oxaliplatin: 682 mg for OxCap+cetuximab vs 806 mg for OxFU+cetuximab. Our study also confirmed that OxCap and OxFU have different toxicity profiles with OxFU being associated with higher rates of G3+ mucositis, neutropenia and treatment-related infections, and OxCap being associated with higher rates of G3+ nausea, diarrhoea and PPE. Of note, more patients on OxFU had G3+ neuropathy, which was limited to Arm A in the individual arm analysis: 22% vs 16% for patients on OxFU and OxCap, respectively. This may be explained by the 6% higher cumulative dose of oxaliplatin for patients on OxFU compared with OxCap in Arm A: 848 and 797 mg, respectively.

The rate of patients who came off their second regimen after switching from OxFU (±cetuximab) to OxCap (±cetuximab) or vice versa was only 16%. This success in switching from one regimen to the other in keeping patients on first-line chemotherapy can be explained by the differing acceptability to patients of specific toxicity profiles.

Patients with CrCl 50–80 ml min−1 on OxCap had more G3+ toxicities and dose delays compared with those of CrCl >80 ml min−1. This discrepancy was not observed between the two CrCl groups in patients on OxFU. However, patients on OxFU+cetuximab with mild renal impairment required more dose modifications compared with patients of CrCl >80 ml min−1 on the same regimen.

In conclusion: (I) OxFU (OxMdG) and OxCap (XELOX) have similar efficacy in the first-line treatment for aCRC. (II) OxFU is a better chemotherapy partner for cetuximab than OxCap because of less diarrhoea and longer PFS. (III) Toxicity patterns differ and thus the risks and preferences for the individual patient should inform the choice between OxCap and OxFU regimens. (IV) Switching to a different oxaliplatin/Fp regimen is a valid option in the event of controlled disease but poor tolerance or compliance and should be considered before abandoning this regimen and moving to a second-line regimen. (V) Patients with mild renal impairment on OxCap or OxFU+cetuximab should be monitored closely for the development of severe toxicities and early and appropriate dose reduction should be instituted if they occur.

Change history

10 September 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Adams RA, Meade AM, Madi A, Fisher D, Kay E, Kenny S, Kaplan RS, Maughan TS (2009) Toxicity associated with combination oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine with or without cetuximab in the MRC COIN trial experience. Br J Cancer 100: 251–258

Adams RA, Meade AM, Seymour MT, Wilson RH, Madi A, Fisher D, Kenny SL, Kay E, Hodgkinson E, Pope M, Rogers P, Wasan H, Falk S, Gollins S, Hickish T, Bessell EM, Propper D, Kennedy MJ, Kaplan R, Maughan TS (2011) Intermittent versus continuous oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet Oncol 12: 642–653

Arkenau HT, Arnold D, Cassidy J, Diaz-Rubio E, Douillard JY, Hochster H, Martoni A, Grothey A, Hinke A, Schmiegel W, Schmoll HJ, Porschen R (2008) Efficacy of oxaliplatin plus capecitabine or infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 26: 5910–5917

Braun MS, Adab F, Bradley C, McAdam K, Thomas G, Wadd NJ, Rea D, Philips R, Twelves C, Bozzino J, MacMillan C, Saunders MP, Counsell R, Anderson H, McDonald A, Stewart J, Robinson A, Davies S, Richards FJ, Seymour MT (2003) Modified de Gramont with oxaliplatin in the first-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 89: 1155–1158

Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Burger U, Garin A, Graeven U, McKendric J, Maroun J, Marshall J, Osterwalder B, Perez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schilsky RL (2002) First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol 13: 566–575

Cassidy J, Clarke S, Diaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzen F, Saltz L (2008) Randomized phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 2006–2012

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976) Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16: 31–41

de Gramont A, Bosset JF, Milan C, Rougier P, Bouche O, Etienne PL, Morvan F, Louvet C, Guillot T, Francois E, Bedenne L (1997) Randomized trial comparing monthly low-dose leucovorin and fluorouracil bolus with bimonthly high-dose leucovorin and fluorouracil bolus plus continuous infusion for advanced colorectal cancer: a French intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 15: 808–815

Diaz-Rubio E, Tabernero J, Gomez-Espana A, Massutí B, Sastre J, Chaves M, Abad A, Carrato A, Queralt B, Reina JJ, Maurel J, González-Flores E, Aparicio J, Rivera F, Losa F, Aranda E (2007) Phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with continuous-infusion fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: final report of the Spanish Cooperative Group for the Treatment of Digestive Tumors Trial. J Clin Oncol 25: 4224–4230

Ducreux M, Bennouna J, Hebbar M, Ychou M, Lledo G, Conroy T, Adenis A, Faroux R, Rebischung C, Bergougnoux L, Kockler L, Douillard JY (2011) Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-6) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 128: 682–690

Hennig IM, Naik JD, Brown S, Szubert A, Anthoney DA, Jackson DP, Melcher AM, Crawford SM, Bradley C, Brown JMB, Seymour MT (2008) Severe sequence-specific toxicity when capecitabine is given after fluorouracil and leucovorin. J Clin Oncol 26: 3411–3417

Maughan TS, Adams RA, Smith CG, Meade AM, Seymour MT, Wilson RH, Idziaszczyk S, Harris R, Fisher D, Kenny SL, Kay E, Mitchell JK, Madi A, Jasani B, James MD, Bridgewater J, Kennedy MJ, Claes B, Lambrechts D, Kaplan R, Cheadle JP (2011) Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet 377: 2103–2114

Porschen R, Arkenau HT, Kubicka S, Greil R, Seufferlein T, Freier W, Kretzschmar A, Graeven U, Grothey A, Hinke A, Schmiegel W, Schmoll HJ (2007) Phase III study of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and leucovorin plus oxaliplatin in metastatic colorectal cancer: a final report of the AIO Colorectal Study Group. J Clin Oncol 25: 4217–4223

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple Imputation For Nonresponse In Surveys. Wiley: New York

Tournigand C, Andre T, Achille E, Lledo G, Flesh M, Mery-Mignard D, Quinaux E, Couteau C, Buyse M, Ganem G, Landi B, Colin P, Louvet C, de Gramont A (2004) FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol 22: 229–237

Van Cutsem E, Hoff PM, Harper P, Bukowski RM, Cunningham D, Dufour P, Graeven U, Lokich J, Madajewicz S, Maroun JA, Marshall JL, Mitchell EP, Perez-Manga G, Rougier P, Schmiegel W, Schoelmerich J, Sobrero A, Schilsky RL (2004) Oral capecitabine vs intravenous 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin: integrated efficacy data and novel analyses from two large, randomised, phase III trials. Br J Cancer 90: 1190–1197

White IR, Royston P (2009) Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat Med 28: 1982–1998

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the 2445 patients and their families who participated in COIN. The design of the Medical Research Council (MRC) COIN trial was conceived and developed by the National Cancer Research Institute aCRC group. The trial was funded by the peer-reviewed Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Advisory and Awards Committee, the MRC and an unrestricted educational grant from Merck kGaA. Additional support in the form of discounted products was provided by Sanofi, Wyeth and Baxter. The MRC was the overall sponsor of the study, with some responsibilities for the Republic of Ireland sites delegated to the All Ireland Cooperative Clinical Research Group. COIN was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency in June 2004 and South-West Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee in December 2004. Approvals for the Irish sites were obtained from the Irish Medicines Board in November 2006 and SJH/AMNCH Research Ethics Committee in December 2006. The trial was coordinated by the MRC Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) following the principles of GCP, conducted with a Trial Management Group, monitored at regular intervals by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee and overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee. Data collection at UK sites was supported by staff funding from the National Cancer Research Networks. All statistical analyses were performed at the MRC CTU. The trial is registered as an International Standard Randomised Controlled trial, number ISRCTN27286448. Tumour mutation analysis was performed at the Institute of Medical Genetics, Cardiff University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Madi, A., Fisher, D., Wilson, R. et al. Oxaliplatin/capecitabine vs oxaliplatin/infusional 5-FU in advanced colorectal cancer: the MRC COIN trial. Br J Cancer 107, 1037–1043 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.384

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.384

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Randomized phase II study of SOX+B-mab versus SOX+C-mab in patients with previously untreated recurrent advanced colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS (MCSGO-1107 study)

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

Upregulated OCT3 has the potential to improve the survival of colorectal cancer patients treated with (m)FOLFOX6 adjuvant chemotherapy

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2019)

-

Capecitabine Versus Continuous Infusion Fluorouracil for the Treatment of Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: a Meta-analysis

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2018)

-

Multicenter Phase II study of FOLFOX or biweekly XELOX and Erbitux (cetuximab) as first-line therapy in patients with wild-type KRAS/BRAF metastatic colorectal cancer: The FLEET study

BMC Cancer (2015)